Atomic-Scale Insights: How Scanning Tunneling Microscopy is Revolutionizing Surface Science and Biomedical Research

This article provides a comprehensive exploration of Scanning Tunneling Microscopy (STM), a technique capable of imaging surfaces at the atomic scale by exploiting quantum tunneling.

Atomic-Scale Insights: How Scanning Tunneling Microscopy is Revolutionizing Surface Science and Biomedical Research

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive exploration of Scanning Tunneling Microscopy (STM), a technique capable of imaging surfaces at the atomic scale by exploiting quantum tunneling. Tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, it covers the foundational principles of STM, from its historical development and quantum mechanical basis to its advanced methodological applications in characterizing catalytic surfaces, biological monolayers, and single-atom catalysts. The scope extends to practical guidance on overcoming key operational challenges like vibration isolation and image interpretation, and concludes with a comparative analysis against complementary techniques. By synthesizing the latest research and future directions, this article serves as a vital resource for leveraging atomic-scale surface imaging to drive innovation in material science and biomedical applications.

The Quantum Mechanical Bridge: Unveiling Atomic Worlds with STM

Scanning Tunneling Microscopy (STM) is an imaging technique of monumental importance in nanotechnology, enabling researchers to obtain ultra-high resolution images of conductive surfaces at the atomic scale without using light or electron beams [1]. Invented in 1981 by Gerd Binnig and Heinrich Rohrer at IBM (an achievement that earned them the Nobel Prize in Physics in 1986), STM was the first technique developed in the larger class of scanning probe microscopy (SPM) [2] [1]. This breakthrough provided significantly more detail than any previous microscopy technique, allowing researchers to map a conductive sample's surface atom by atom and precisely characterize its three-dimensional topography and electronic density of states [1]. The operation of STM represents a rare and remarkable example of harnessing a quantum mechanical process—electron tunneling—in a practical real-world application, revolutionizing fundamental and industrial research across physics, chemistry, and materials science [1].

The Quantum Tunneling Principle

Fundamental Concept

The core physical principle that enables STM is the quantum mechanical phenomenon of electron tunneling. In classical physics, an electron confronting a potential barrier higher than its kinetic energy would be completely reflected. However, quantum mechanics reveals that electrons possess a wave-like character that allows them to traverse such barriers [1]. This occurs because electrons do not exist as discrete points but as "fuzzy" probability clouds described by wavefunctions. When an electron cloud encounters a thin potential barrier, there is a non-zero probability that the electron will appear on the other side rather than being reflected [1].

In the specific context of STM, the potential barrier is the vacuum or air gap between the microscope's sharp conductive probe tip and the conductive sample surface. When this gap is reduced to approximately 1 nanometer or less, the electron clouds of the tip atom and surface atoms begin to overlap [1]. If a bias voltage is applied between the tip and sample in this configuration, electrons are driven to tunnel through the potential barrier, generating a measurable tunneling current [1].

Exponential Distance Dependence

The tunneling current (I) exhibits an exponential dependence on the tip-sample separation (d), following the relationship: I ∝ Vₛ × e^(-2κd)

Where Vₛ is the bias voltage and κ is the decay constant determined by the local work function of the material [1]. This exponential relationship makes the tunneling current extraordinarily sensitive to minute changes in distance—typically changing by an order of magnitude for every 0.1 nanometer variation in separation [1]. It is this remarkable sensitivity that ultimately enables STM to achieve atomic-scale resolution, as the tunneling current effectively probes the electronic density of states at the surface with sub-atomic precision.

Figure 1: Quantum Tunneling Principle - Comparison of classical prediction versus quantum mechanical reality in STM operation.

STM Operational Modes

Constant Current Mode

Constant current mode is the more commonly used operational mode in STM experiments [1]. In this mode, a feedback loop system actively maintains the tunneling current at a predetermined constant value by continuously adjusting the vertical position (z-height) of the probe tip relative to the sample surface [1]. When the tunneling current exceeds the target setpoint, indicating either a protrusion on the surface or a region of higher local electron density, the feedback system retracts the tip to increase the tip-sample distance. Conversely, if the current falls below the setpoint, indicating a depression or region of lower electron density, the system moves the tip closer to the surface [1]. The resulting three-dimensional map of the tip's vertical movements as a function of (x,y) position produces a topographical image representing surfaces of constant electron density, which generally corresponds to the physical topography of the surface [1]. This mode is particularly advantageous for imaging rough or irregular surfaces where maintaining a constant height might risk damaging the tip or sample.

Constant Height Mode

In constant height mode, the probe tip travels at a fixed vertical position above the sample surface while rapidly raster scanning across it [1]. Variations in the surface topography or electronic structure cause measurable changes in the tunneling current, which are recorded directly to construct the image [1]. This mode is generally reserved for imaging exceptionally smooth surfaces where the risk of tip-sample collision is minimal [1]. The primary advantage of constant height mode is its faster scanning capability, as it eliminates the response time limitations of the feedback loop system. This enables researchers to capture dynamic surface processes or to survey larger areas more efficiently. The resulting images represent maps of electronic density of states rather than direct topographical profiles, providing complementary information about the surface's electronic properties [1].

Table 1: Comparison of STM Operational Modes

| Parameter | Constant Current Mode | Constant Height Mode |

|---|---|---|

| Feedback Loop | Active: maintains constant current | Inactive: current variations are measured |

| Tip Movement | Vertical (z) adjustment continuously | Fixed z-position during scanning |

| Scanning Speed | Slower due to feedback response | Faster, no feedback limitations |

| Best For | Rough, irregular surfaces | Atomically flat, smooth surfaces |

| Output | Topography (constant electron density) | Electronic density of states map |

| Risk of Crash | Lower, maintained separation | Higher, fixed clearance |

Advanced STM Imaging Techniques

Bias-Dependent Imaging and Three-Color Composite

Advanced STM techniques leverage the relationship between tunneling bias and apparent topography to extract additional information about surface properties. The three-color composite process is one such technique that capitalizes on the fact that sample surfaces often exhibit strong bias-dependent apparent topography [3]. This occurs because the STM tip actually follows the local density of states rather than the physical topography alone, and this density of states varies with the energy of the tunneling electrons, which is determined by the applied bias voltage [3].

In this technique, three individual STM images of the identical sample area are acquired at different tunneling bias voltages. These images are subsequently combined in RGB mode, typically with the lowest bias image assigned to the red channel, an intermediate bias to green, and the highest bias to blue [3]. The resulting color image contains information about how the electronic structure of the surface varies with energy, which often correlates with chemical composition, adsorbates, or structural variations that might be indistinguishable in a single-bias topograph [3]. The color variations within a single image have physical meaning, though absolute colors between different images cannot be directly compared due to contrast normalization [3].

Tunneling Spectroscopy

Scanning Tunneling Spectroscopy (STS) extends STM beyond topographic imaging to directly probe the local electronic structure of surfaces. By positioning the tip at a fixed location above the surface and measuring the tunneling current as a function of applied bias voltage, researchers can obtain dI/dV spectra that reveal the local density of states (LDOS) of the sample [3]. This spectroscopic information can be spatially mapped across a surface by acquiring spectra at regular intervals in a grid pattern, creating a detailed picture of how electronic properties vary at the nanoscale.

When combined with the three-color composite technique, tunneling spectroscopy can provide the color information used to enhance a high-resolution STM topograph [3]. This powerful combination allows researchers to correlate atomic-scale structural features with their corresponding electronic properties, providing crucial insights for understanding catalytic activity, molecular orbital distributions, defect states, and other electronic phenomena at surfaces.

Experimental Protocols

Standard STM Imaging Procedure

Objective: To obtain atomic-resolution images of a conductive sample surface using scanning tunneling microscopy.

Materials and Equipment:

- Scanning Tunneling Microscope system

- Conductive probe tip (Pt-Ir, W, or other suitable material)

- Conductive sample (e.g., Highly Oriented Pyrolytic Graphite - HOPG, metal single crystal)

- Vibration isolation platform

- Sample preparation tools (cleavage tools, solvents, plasma cleaner if needed)

Procedure:

Sample Preparation

- For layered materials like HOPG, cleave the top layers using adhesive tape to expose a fresh, atomically flat surface.

- For other materials, employ appropriate cleaning procedures (e.g., argon sputtering, annealing, electrochemical etching) to ensure a clean, well-defined surface.

- Mount the sample securely on the STM sample holder, ensuring good electrical contact.

Tip Preparation

- Prepare a sharp conductive tip using appropriate methods (electrochemical etching for metal wires, mechanical cutting for Pt-Ir wires).

- Confirm tip sharpness and quality by performing test scans on a reference sample if available.

Microscope Setup

- Engage vibration isolation system.

- Approach the tip toward the sample using coarse approach mechanism until tunneling range is reached (typically indicated by a predefined current threshold).

- Set initial imaging parameters: bias voltage = 0.1-1.0 V, tunneling current = 0.1-1.0 nA (adjust based on sample and desired resolution).

Image Acquisition

- Select scanning area size (typically starting with larger areas - 1 μm × 1 μm - then progressing to smaller areas for higher resolution).

- Choose operational mode (constant current recommended for initial imaging).

- Begin scanning, monitoring image quality and adjusting parameters as needed.

- For atomic resolution, reduce scan size to 5-10 nm, optimize feedback loop gains to ensure stable tracking without oscillations.

Data Processing

- Apply necessary image processing (plane subtraction, flattening) to correct for sample tilt and thermal drift.

- Analyze surface features, defects, and periodic structures.

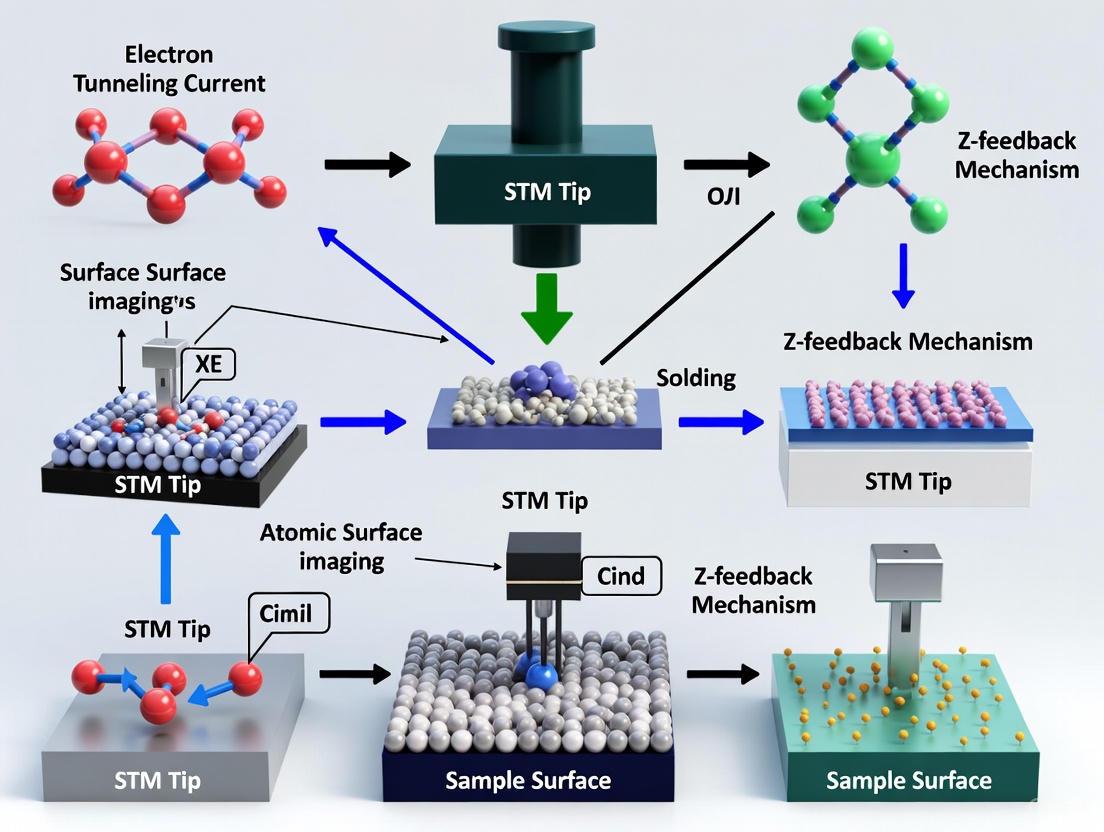

Figure 2: Complete STM experimental workflow from sample preparation to data analysis.

Three-Color Composite Imaging Protocol

Objective: To create color-enhanced STM images that encode bias-dependent electronic structure information.

Materials and Equipment:

- STM system capable of stable imaging over extended periods

- Thermally stable environment (to minimize drift during long acquisitions)

- Image processing software (e.g., ImageJ, Corel Photo-Paint, Adobe Photoshop)

Procedure:

Locate Region of Interest

- Identify a suitable sample area with features of interest using standard STM imaging.

- Ensure the area displays minimal drift and stable tunneling conditions.

Multi-Bias Image Acquisition

- Acquire three STM images of the identical region at different bias voltages.

- Typical bias settings: 0.3 V (low), 0.8 V (medium), 1.2 V (high) - adjust based on sample properties [3].

- Maintain constant tunneling current setpoint across all acquisitions.

- Ensure minimal sample drift between images by allowing thermal equilibration.

Image Registration

- Align the three images to correct for any residual thermal drift.

- Use cross-correlation or landmark-based alignment methods.

RGB Composite Creation

Color Enhancement

- Enhance color saturation by a factor of 2-3 to improve visual differentiation [3].

- Avoid altering color balance or applying artificial colorization.

- Document all processing steps for reproducibility.

Interpretation

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential STM Research Reagents and Materials

Table 2: Essential Materials for STM Research

| Material/Reagent | Function/Application | Specifications |

|---|---|---|

| Conductive Probe Tips | Serves as scanning probe for tunneling current | Pt-Ir, W, or Au wires; electrochemically etched to atomic sharpness (tip radius < 50 nm) |

| HOPG (Highly Oriented Pyrolytic Graphite) | Standard calibration sample; atomically flat surface | ZYA grade recommended for minimal defects; freshly cleaved before use |

| Single Crystal Metal Substrates | Well-defined surfaces for fundamental studies | Au(111), Cu(111), Pt(111) with terraces of ≥100 nm width |

| Ultrasonic Cleaner | Cleaning tips and sample holders | Frequency: 40-50 kHz; with suitable solvents (acetone, ethanol, isopropanol) |

| Electrochemical Etching Setup | Sharpening metal wires for STM tips | DC power supply, electrolyte solution (e.g., 2M NaOH for W, CaCl₂ for Pt-Ir) |

| Vibration Isolation System | Minimizes mechanical noise | Active or passive isolation with natural frequency < 1 Hz |

| Sample Cleaving Tools | Creating fresh surfaces for imaging | Adhesive tape for layered materials; diamond scribe for brittle materials |

Applications in Surface Science Research

STM has enabled groundbreaking research across numerous disciplines by providing unprecedented atomic-scale characterization capabilities. In surface chemistry, STM has revealed the atomic structure of surface reconstructions, identified active sites for catalytic reactions, and visualized reaction intermediates adsorbed on surfaces [1]. The technique has been particularly instrumental in understanding self-assembled monolayers of organic molecules on various substrates, where it can resolve single molecules and even sub-molecular structure [1].

In nanotechnology, STM has progressed from a passive observation tool to an active manipulation instrument. Researchers have used STM tips to precisely position individual atoms on surfaces, creating quantum corrals, molecular switches, and custom nanostructures that exhibit unique quantum phenomena [1]. This atom manipulation capability has opened new possibilities for constructing nanoscale devices and studying fundamental quantum effects in confined systems.

More recently, advanced STM techniques have been applied to complex materials systems including molecular self-assembly, where STM has revealed the structural details of two-dimensional molecular lattices and moiré patterns [1]. Low-current STM operating at tunneling currents as low as 300 femtoamps has enabled higher resolution imaging of delicate molecular systems without disturbing the native structure [1]. These applications demonstrate how STM continues to evolve and provide valuable insights into the atomic-scale world, nearly four decades after its invention.

The invention of the Scanning Tunneling Microscope (STM) at the IBM Zurich Research Laboratory in 1981 marked a paradigm shift in surface science, providing researchers with the first-ever tool capable of visualizing and manipulating matter at the atomic level. Developed by physicists Gerd Binnig and Heinrich Rohder, this groundbreaking instrument earned its inventors the Nobel Prize in Physics in 1986 for an invention that would fundamentally reshape nanotechnology and materials science [4] [5]. The STM achieved what was previously thought impossible: imaging surfaces with a depth resolution of approximately 0.01 nm, allowing individual atoms to be routinely observed and manipulated [6]. By transcending the limitations of optical wavelength that constrained traditional microscopes, the STM unlocked a new realm of scientific inquiry based on the quantum mechanical phenomenon of electron tunneling [5].

The significance of this breakthrough extends far beyond fundamental physics. For researchers and drug development professionals, the STM and its subsequent progeny of scanning probe microscopes have created unprecedented opportunities for characterizing materials, studying biological molecules, and engineering nanostructures with precision. This application note details the operational principles, standardized protocols, and practical applications of STM technology, contextualized within its historical development from IBM laboratories to Nobel Prize recognition and contemporary research applications.

Theoretical Foundation: Harnessing Quantum Tunneling

The Quantum Mechanical Principle

The operational principle of STM relies exclusively on the quantum mechanical effect known as electron tunneling [1] [6]. When a sharp metallic tip approaches a conductive surface to within a distance of approximately 1 nanometer, a phenomenon occurs that defies classical physics: electrons can traverse the vacuum barrier between the tip and sample despite the absence of physical contact [1]. This tunneling effect arises from the wave-like nature of electrons, which enables a non-zero probability for electrons to cross a potential barrier that would be impenetrable according to classical mechanics [6].

The tunneling current ((I)) that forms the basis of STM imaging exhibits an exponential dependence on the tip-sample separation ((d)), following the relationship:

(I \propto V_b e^{-A \sqrt{\phi}d})

where (V_b) is the bias voltage applied between tip and sample, (\phi) is the average work function of the two materials, and (A) is a constant [6]. This exponential relationship makes the tunneling current exceptionally sensitive to minute changes in distance, with variations on the order of 0.1 nm producing measurable changes in current—the fundamental basis for atomic resolution [6].

Operational Modes of STM

The STM operates in two primary imaging modes, each with distinct advantages for specific applications:

Constant Current Mode: In this more commonly used mode, a feedback loop continuously adjusts the tip height to maintain a constant tunneling current during scanning [1] [6]. The resulting voltage applied to the z-axis piezoelectric scanner creates a topographic map that convolves both surface topography and local electronic structure [6]. This mode is particularly valuable for rough surfaces where tip crash is a concern, as the feedback mechanism maintains a relatively constant tip-sample separation.

Constant Height Mode: In this faster acquisition mode, the tip remains at a nearly constant height while variations in tunneling current are directly recorded [1] [6]. This mode is generally restricted to atomically flat surfaces but enables rapid imaging, making it suitable for observing dynamic surface processes [6].

Table 1: Comparison of STM Operational Modes

| Parameter | Constant Current Mode | Constant Height Mode |

|---|---|---|

| Feedback Loop | Active | Inactive |

| Scan Speed | Slower | Faster |

| Primary Output | Tip height adjustments | Tunneling current variations |

| Surface Compatibility | All surfaces, especially rough | Atomically flat surfaces |

| Resolution Considerations | Contains topographical and electronic information | Primarily electronic structure |

| Risk of Tip Crash | Lower | Higher on rough surfaces |

Instrumentation and Research Reagents

Core STM Components

A scanning tunneling microscope consists of several sophisticated subsystems that must operate in concert to achieve atomic resolution:

Scanning Tip: The tip represents the most critical component, typically fabricated from tungsten, platinum-iridium, or gold wires [6] [7]. Tip sharpness directly determines image resolution, with ideal tips terminating in a single atom [6]. Preparation methods include electrochemical etching for tungsten tips and mechanical shearing for PtIr alloys [6].

Piezoelectric Scanner: These components provide precise tip or sample positioning with sub-angstrom resolution [6]. Most modern STMs use hollow tube scanners constructed from lead zirconate titanate ceramics, which exhibit piezoelectric constants of approximately 5 nm/V [6]. Electrodes on the scanner tube enable three-dimensional positioning by applying appropriate control voltages.

Vibration Isolation System: Due to the extreme sensitivity of tunneling current to distance variations, sophisticated vibration damping is essential. Early STMs used magnetic levitation, while contemporary systems employ mechanical spring or gas spring systems, often supplemented with eddy current damping [6]. Systems designed for high-resolution spectroscopy may require anechoic chambers with acoustic and electromagnetic isolation [6].

Control Electronics and Software: Dedicated electronics regulate the bias voltage, measure tunneling current (typically in the sub-nanoampere range), and control the piezoelectric scanners [6]. Sophisticated software handles data acquisition, image processing, and quantitative analysis of surface properties.

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Materials for STM Research

| Material/Reagent | Function/Application | Specifications |

|---|---|---|

| Platinum-Iridium (PtIr) Tips | Standard tip material for general purpose STM | 80/20 PtIr alloy, mechanically sheared [7] [6] |

| Tungsten (W) Tips | High-resolution imaging in UHV | Electrochemically etched, radius <100 nm [6] |

| Gold Single Crystals | Standard substrate for calibration | Au(111) with herringbone reconstruction [7] |

| Highly Oriented Pyrolytic Graphite (HOPG) | Atomically flat substrate for ambient conditions | Freshly cleaved surface [1] |

| Argon Gas | Surface cleaning via sputtering | High purity (99.999%), 1-5 keV energy [7] |

| 5-octadecoxyisophthalic acid | Molecular self-assembly studies | Forms self-assembled monolayers on HOPG [1] |

| Nickel Octaethylporphyrin (NiOEP) | Molecular electronics research | Forms 2D lattices on HOPG for electronic studies [1] |

Experimental Protocols

Tip Preparation and Characterization Protocol

Reproducible tip preparation is essential for reliable STM operation, particularly for applications requiring atomic resolution or spectroscopic measurements. The following protocol, adapted from contemporary research practices, details a procedure for in situ tip conditioning [7]:

Step 1: Initial Tip Approach

- Bring the tip within tunneling range of a clean metal surface (typically Au(111)) using coarse positioning mechanisms.

- Establish tunneling conditions with parameters set to: bias voltage = 100 mV, tunneling current = 1 nA.

Step 2: Mechanical Annealing Cycles

- Program controlled indentation cycles using a custom MATLAB script or equivalent control software.

- Execute tip approach at a constant rate of 0.5 Å/s until reaching a predetermined conductance value, typically the quantum conductance unit (G_0 = 2e^2/h) for gold contacts [7].

- Immediately retract the tip completely from contact after reaching the target conductance.

- Repeat this process for 50-100 cycles while monitoring conductance traces for reproducibility.

Step 3: Tip Quality Verification

- Image a known surface feature, such as a single adatom deposited on Au(111).

- Assess image symmetry; asymmetric adatom images indicate tip asymmetry requiring further conditioning [7].

- For quantitative assessment, perform scanning tunneling spectroscopy on a standard surface to verify electronic feature reproducibility.

This mechanical annealing procedure induces plastic deformation at the tip apex, gradually evolving toward a stable, crystalline structure that produces reproducible conductance traces and enhanced image quality [7].

High-Resolution Imaging Protocol for HOPG

Highly Oriented Pyrolytic Graphite (HOPG) serves as a standard calibration sample for STM due to its atomically flat surfaces and well-characterized atomic structure. The following protocol ensures optimal imaging conditions:

Step 1: Substrate Preparation

- Cleave HOPG surface immediately before imaging using adhesive tape to expose fresh, contamination-free basal planes.

- Mount sample securely to minimize thermal drift during imaging.

Step 2: Imaging Parameter Optimization

- For ambient conditions, set tunneling parameters to: bias voltage = 10-50 mV, tunneling current = 1 nA.

- Engage feedback loop with moderate gain settings to ensure stable tracking without oscillations.

- Select constant current mode for initial survey scans, transitioning to constant height mode for high-speed atomic resolution imaging on flat terraces.

Step 3: Data Acquisition

- Acquire initial large-scale images (500×500 nm) to identify suitable atomically flat regions.

- Progress to smaller scan sizes (10×10 nm) for atomic resolution.

- Set scan speed to 1-2 Hz per line to balance signal-to-noise ratio and temporal resolution.

Step 4: Image Processing and Analysis

- Apply plane correction to compensate for sample tilt.

- Use Fourier filtering to enhance periodic structures while minimizing high-frequency noise.

- Measure lattice parameters against known HOPG structure (triangular lattice with 2.46 Å interatomic spacing).

Molecular Self-Assembly Imaging Protocol

Self-assembled monolayers (SAMs) represent important model systems for surface functionalization and molecular electronics. The following protocol details procedures for imaging molecular assemblies:

Step 1: Sample Preparation

- Prepare solution of target molecule (e.g., 5-octadecoxyisophthalic acid) in appropriate solvent at 0.1-1 mM concentration.

- Deposit solution droplet onto freshly cleaved HOPG surface and allow incubation for 1-5 minutes.

- Rinse gently with pure solvent to remove physisorbed multilayers and blow-dry with inert gas.

Step 2: STM Imaging Conditions

- Optimize tunneling parameters for molecular imaging: bias voltage = 500-800 mV, tunneling current = 50-200 pA.

- Use low-current settings (300 fA - 60 pA) for high-resolution imaging of molecular orbitals [1].

- Employ constant height mode to capture electronic structure details without feedback-induced artifacts.

Step 3: Data Interpretation

- Correlate observed molecular patterns with known molecular dimensions and symmetry.

- Identify domain boundaries and structural defects in the self-assembled lattice.

- Compare experimental images with molecular modeling to confirm molecular orientation and packing density.

Diagram 1: STM Experimental Workflow

Advanced Applications and Case Studies

Single-Atom Manipulation and Quantum Corrals

A landmark demonstration of STM capabilities occurred in 1990 when IBM researchers used the microscope to manipulate individual xenon atoms on a nickel surface, spelling out the letters "IBM" [4]. This unprecedented feat established the STM as both an imaging tool and a fabrication instrument at the atomic scale. The manipulation process involves:

- Positioning the STM tip directly above a target atom at low temperature (4 K) to minimize thermal diffusion.

- Lowering the tip to increase interaction strength between tip and atom.

- Dragging the atom across the surface by moving the tip while maintaining contact.

- Retracting the tip once the atom reaches the desired position.

This capability enabled the creation of "quantum corrals"—carefully arranged atom arrays on metal surfaces that confine surface electrons, creating standing wave patterns that can be directly visualized with STM [1]. These structures provide direct observation of quantum mechanical phenomena and enable fundamental studies of electron behavior in confined geometries.

Scanning Tunneling Spectroscopy (STS) and Electronic Structure Mapping

Scanning Tunneling Spectroscopy extends STM capabilities beyond topography to map the local electronic density of states (LDOS) with atomic resolution. Standard STS protocols include:

- I-V Spectroscopy: At fixed tip position, disabling the feedback loop and sweeping the bias voltage while measuring tunneling current reveals sample electronic structure at specific locations [6].

- dI/dV Mapping: Recording the differential conductance ((dI/dV)) as a function of position provides spatial maps of the LDOS at specific energies, particularly valuable for identifying impurities, defects, and quantum states [6].

- Barrier Height Measurements: Modulating the tip-sample distance while monitoring current variations yields information about the local tunnel barrier, related to surface work function.

These spectroscopic techniques have proven invaluable in characterizing semiconductor materials, high-temperature superconductors, and single-molecule electronics.

Table 3: Spectroscopy Parameters for Various Material Systems

| Material System | Bias Voltage Range | Key Spectral Features | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Metals (Au, Ag, Cu) | ±1 V | Nearly featureless LDOS | Surface state mapping at low biases |

| Semiconductors (Si, GaAs) | ±2 V | Band edges, surface states | Careful Fermi level positioning critical |

| High-Tc Superconductors | ±20 mV | Superconducting gap | Requires low temperatures (4 K) |

| Single Molecules | ±0.5 V | Frontier orbital resonances | Avoid high voltages that induce conformational changes |

Environmental STM and Electrochemical Applications

STM operation under various environmental conditions significantly expands its application potential. Modifications to standard ultra-high vacuum (UHV) configurations enable studies in:

- Ambient Conditions: Standard laboratory air with vibration isolation and acoustic noise reduction enables imaging of biological samples and molecular self-assembly [1].

- Liquid Environments: Specialized tips with insulation exposing only the very apex allow STM operation in electrochemical cells for in situ studies of electrode processes, corrosion, and electrodeposition [1].

- Variable Temperature: Systems operating from near 0 K to over 1000°C facilitate investigations of temperature-dependent phenomena including surface diffusion, phase transitions, and reaction kinetics [1] [6].

Diagram 2: STM Application Domains

Future Perspectives and Emerging Methodologies

The evolution of scanning tunneling microscopy continues with several promising developments expanding the technique's capabilities:

- Low-Current STM: Advanced electronics enabling stable operation at tunneling currents as low as 300 femtoamperes provide enhanced resolution for delicate molecular systems while minimizing tip-sample interactions [1].

- High-Speed STM: Video-rate imaging at 80 Hz frame rates captures dynamic surface processes in real time, including diffusion, reaction kinetics, and molecular switching events [6].

- Multi-Probe STM: Systems incorporating multiple independent tips enable four-point resistance measurements and complex device characterization at the nanoscale.

- Combined SPM Techniques: Integration with atomic force microscopy (AFM) and other scanning probe methods provides complementary information about both electronic and mechanical properties with atomic resolution [1].

These advancements ensure STM's continued relevance in nanotechnology, particularly in the development of quantum materials, molecular machines, and next-generation electronic devices. The transition from IBM's pioneering instrument to today's sophisticated research tools exemplifies how fundamental breakthroughs in measurement technology can catalyze entire fields of scientific inquiry, from basic surface science to applied drug development and materials engineering.

The legacy of Binnig and Rohrer's invention extends far beyond its Nobel Prize recognition—it has established a paradigm for nanotechnology research that continues to evolve, enabling scientists to not only see the atomic world but to engineer it with increasing precision. For researchers and drug development professionals, STM and its derivative technologies offer powerful approaches to characterize materials and biological systems at the fundamental scale where molecular interactions determine macroscopic properties and functions.

The scanning tunneling microscope (STM), since its Nobel Prize-winning inception, has become an indispensable tool in nanotechnology and atomic-scale surface research [8] [9]. Its unique ability to probe the structural and electronic properties of surfaces with sub-atomic resolution has profound implications for fundamental physics, materials science, and drug development, where understanding molecular interactions at the atomic level is critical. The operational prowess of the STM rests on three fundamental pillars: the piezoelectric scanner, which enables angstrom-precise positioning; the scanning tip, which serves as the primary sensor for electron tunneling; and the feedback loop, which maintains stable imaging conditions [10] [9]. This application note details these core components, providing structured quantitative data, detailed experimental protocols, and essential workflows to guide researchers in the field of atomic surface imaging.

Core Components and Technical Specifications

Piezoelectric Scanners

Piezoelectric materials form the mechanical backbone of all STMs, converting electrical voltages into precise physical movements. They are utilized in scanners to position the tip relative to the sample with sub-angstrom precision in three dimensions [9].

Table 1: Performance Characteristics of Piezoelectric Tube Scanners

| Characteristic | Standard Single-Tube Scanner | Stacked Piezo Tube Scanner [10] | Implication for STM Performance |

|---|---|---|---|

| XY Scanning Principle | Raster pattern (triangular wave) | Raster pattern (triangular wave) | Standard method for area imaging |

| Z Direction Control | High-voltage electrode | High-voltage electrode | Maintains constant tunneling current |

| Lateral (X-Y) Drift Rate | Typically >100 pm/min | 22.8 pm/min (at 300 K) [10] | Critical for long-term stability & large-area imaging |

| Vertical (Z) Drift Rate | Typically >100 pm/min | 31.1 pm/min (at 300 K) [10] | Determines height measurement stability |

| Key Nonlinearities | Hysteresis, Creep, Vibration [11] [12] | Hysteresis, Creep, Vibration | Causes image distortion, requires compensation |

| Optimal Operating Temp. | Room Temperature (300 K) | Room Temperature (300 K) and 2 K [10] | Enables diverse experimental conditions |

The performance of piezoelectric scanners is limited by inherent nonlinear dynamics, including hysteresis, creep, and temperature-dependent behavior, which adversely affect image quality unless compensated by a controller [11] [12]. A recent innovation to overcome these challenges is the stacked piezo tube design [10]. This configuration uses two piezo tubes to function as a single coarse stepper motor during tip approach, summing their output forces for reliability. For atomic-resolution imaging, only the shorter tube is used, which, due to its smaller size, is less susceptible to external disturbances, thereby enhancing imaging accuracy and stability while allowing for a more compact STM head [10].

Scanning Tunneling Microscope Tips

The STM tip is the primary probe for surface interaction. While the search results do not provide an exhaustive list of tip specifications, the fundamental principles are well-established.

Table 2: Research Reagent Solutions - STM Tip Specifications

| Tip Material | Common Fabrication Method | Key Function and Properties | Applicable Experiments |

|---|---|---|---|

| Tungsten (W) | Electrochemical etching | Hard material; requires in-situ cleaning via high-bias field-emission to ensure a flat density of states (DOS) [9]. | General topographic imaging, dI/dV spectroscopy |

| Platinum-Iridium (PtIr) | Mechanical cutting | Chemically inert; often used without further processing. Assumption of a flat DOS is confirmed via I-V curves on metal substrates [9]. | Ambient condition imaging, electrochemical STM |

| Gold (Au) Substrate | Not applicable | Standard substrate for tip processing and characterization. Used to confirm a flat tip DOS via field emission [9]. | Tip preparation and calibration |

The tip's electronic structure is paramount. For accurate spectroscopy, the tip must have a featureless density of states around the Fermi level, which is typically achieved and verified through high-bias field-emission on a clean metal surface like Au(111) [9].

Feedback Control Systems

The feedback loop is the intelligent system that actively maintains the tunneling gap during scanning.

Table 3: Feedback Control Methodologies for STM/AFM

| Control Method | Principle | Key Parameters | Advantages & Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Constant Current Topography (STM) [9] | Feedback adjusts tip height (Z) to maintain a setpoint tunneling current (I~set~) at fixed bias (V). | Setpoint Current (I~set~), Bias Voltage (V), PID gains | Most common STM mode; maps surface contour convoluted with electronic structure. |

| Data-Driven Feedforward (AFM) [11] | Compensates piezoelectric hysteresis by pre-distorting scan waveforms. No lateral sensors required. | Identified hysteresis mappings from image pairs. | Ideal for high-speed AFM; mitigates image distortion without added sensors. |

| Strain Gauge Feedback (AFM) [13] | Uses a sensor (e.g., strain gauge) on the Z-piezo for direct position measurement. | Z Sensor Signal | Provides linear metrology for force curves; reduces hysteresis in topography. |

In Constant Current Mode, the most common STM imaging mode, the tip is rastered across the surface at a fixed bias voltage (V) [9]. The feedback loop continuously adjusts the tip's Z-position to keep the measured tunneling current at a predefined setpoint value (I~set~). The resulting trajectory of the Z-piezo is recorded as the topograph [9]. It is critical to understand that this topograph is not a pure geometric profile but a convolution of surface topography and the local electronic density of states (DOS) of the sample [9].

The following diagram illustrates the signaling pathway of this core feedback loop.

Experimental Protocols

Protocol: Atomic-Resolution Topographic Imaging on Graphite

This protocol is adapted from the methodology used to validate the performance of a novel stacked-piezo STM, which achieved high-quality atomic resolution at both room temperature and 2 K [10].

1. Sample Preparation:

- Cleaving: Obtain a fresh, atomically flat surface by mechanically cleaving a highly oriented pyrolytic graphite (HOPG) sample using adhesive tape immediately before loading it into the STM.

2. Tip Preparation and Approach:

- Tip Selection: Install a chemically etched Tungsten (W) or a mechanically cut PtIr tip.

- Coarse Approach: Use the stepper motor or the coarse approach mechanism of the STM to bring the tip to within a few micrometers of the sample surface.

- Fine Approach: Engage the piezo scanner to slowly advance the tip until a tunneling current is detected (e.g., 0.1-1 nA at a bias of 10-100 mV).

3. Feedback Loop Engagement and Imaging:

- Set Feedback Parameters: Set the bias voltage to a low value (e.g., V = 10-30 mV) and the setpoint current to I~set~ = 0.5-1 nA.

- Optimize PID Gains: Adjust the proportional (P), integral (I), and derivative (D) gains of the feedback controller to achieve a stable response without oscillations. This is critical for high-resolution imaging.

- Start Raster Scan: Initiate a slow-speed raster scan over a small area (e.g., 5 nm x 5 nm). The feedback system will now actively maintain a constant tunneling current by moving the Z-piezo, and this Z-position data will be recorded as the topographic image.

4. Performance Validation:

- Assess Stability: Verify the instrument's stability by confirming low drift rates. The stacked-piezo STM demonstrated lateral and vertical drift rates as low as 22.8 pm/min and 31.1 pm/min, respectively [10].

- Atomic Resolution: A successful experiment will reveal the characteristic hexagonal atomic lattice of the graphite surface.

Protocol: Differential Conductance (dI/dV) Spectroscopy

This protocol details the procedure for acquiring local density of states (LDOS) spectra, a powerful extension of STM [9].

1. Acquire Topograph:

- First, obtain a constant-current topograph of the region of interest using the protocol in Section 3.1.

2. Position Tip and Configure Lock-in Amplifier:

- Positioning: Move the tip to the specific (x,y) location on the surface where the spectrum is desired.

- Lock-in Setup: Configure a lock-in amplifier to add a small, high-frequency sinusoidal modulation dV (typical amplitude 1-10 mV, frequency ~1-5 kHz) to the DC bias voltage V.

3. Data Acquisition:

- Disable Feedback: Turn off the feedback loop. This fixes the tip-sample distance (s).

- Sweep DC Bias: Sweep the DC bias voltage V over the desired energy range (e.g., from -1 V to +1 V).

- Measure dI/dV: At each bias point, the lock-in amplifier directly measures the differential conductance dI/dV, which is proportional to the sample's local density of states at energy ε = eV [9]. The relationship is: ρ~s~(eV) ∝ dI/dV.

The workflow for this spectroscopic measurement is outlined below.

Advanced Applications and Material Property Mapping

Beyond topography, STM and its relative, Atomic Force Microscopy (AFM), can be used to map a wide range of material properties by leveraging different feedback signals and operational modes [14] [8]. These techniques are invaluable in drug development for characterizing the mechanical and chemical properties of surfaces and biomolecules.

Key AFM Modes for Material Characterization [8]:

- Phase Imaging: In tapping mode AFM, the phase shift between the driving oscillation and the cantilever's response is sensitive to energy dissipation, enabling the mapping of viscoelastic properties, adhesion, and friction.

- Piezoresponse Force Microscopy (PFM): A conductive tip applies an AC voltage to the surface, and the resulting local piezoelectric deformation is measured. This allows for the imaging of ferroelectric domains in materials.

- Kelvin Probe Force Microscopy (KFM): This mode measures the contact potential difference (work function) between the tip and sample, providing a map of surface potential with high spatial resolution.

The performance and reliability of scanning tunneling microscopy for atomic-scale research are fundamentally determined by the intricate interplay between its core components: high-precision piezoelectric scanners, well-characterized tips, and robust feedback loops. The continuous development of these elements—exemplified by innovations like the stacked piezo tube scanner for enhanced stability and miniaturization—pushes the boundaries of what is possible in nanoscale imaging and spectroscopy [10]. Mastery of the associated experimental protocols, from fundamental topographic imaging to advanced spectroscopic techniques, empowers researchers to not only visualize but also quantitatively analyze the structural and electronic landscape of surfaces, providing critical insights for fields ranging from quantum materials to pharmaceutical sciences.

Scanning Tunneling Microscopy (STM) revolutionized surface science by providing the first real-space imaging technique capable of achieving atomic-scale resolution. Developed in 1981 by Gerd Binnig and Heinrich Rohrer at IBM Zürich—an achievement that earned them the Nobel Prize in Physics in 1986—STM operates not by using light or electron beams, but by exploiting the quantum mechanical phenomenon of electron tunneling [6] [1]. This technique enables researchers to map a conductive sample's surface atom by atom, revealing details of surface topography and electronic structure with unprecedented resolution. The profound sensitivity of STM stems from the exponential dependence of the tunneling current on the tip-sample separation, where changes as small as 0.01 nm (10 pm) can be detected [6] [15].

The operation of all STM systems relies on bringing an atomically sharp conductive tip extremely close (typically <1 nm) to a conductive or semiconducting sample surface. When a bias voltage is applied between them, electrons tunnel through the vacuum barrier, generating a measurable current [1]. The two primary imaging modes—constant-current and constant-height—differ in how they utilize this tunneling current to extract information about the sample surface. The choice between these modes represents a fundamental trade-off between resolution capability, scan speed, and operational safety, with each mode offering distinct advantages for specific experimental conditions and research objectives. Understanding the underlying principles, instrumentation requirements, and practical applications of each mode is essential for optimizing STM experiments in atomic-scale surface research.

Fundamental Principles of STM Operation

Quantum Tunneling Phenomenon

The operational principle of STM rests entirely on the quantum mechanical phenomenon of electron tunneling, which allows electrons to traverse a classically impenetrable potential barrier. According to classical physics, a particle encountering a barrier with energy greater than its kinetic energy would be completely reflected. However, quantum mechanics predicts that particles such as electrons have a finite probability of appearing on the other side of the barrier due to their wave-like nature [6] [1].

In the STM configuration, the vacuum gap between the tip and sample forms this potential barrier. The wavefunction of an electron does not terminate abruptly at a barrier but rather decays exponentially within it. This decaying wavefunction can couple with states on the opposite side, enabling tunneling when the barrier width is sufficiently narrow (typically on the order of nanometers). The resulting tunneling current ((I_t)) follows the relationship:

(It \propto Vb e^{-k d})

Where (V_b) is the applied bias voltage, (d) is the tip-sample separation, and (k) is a constant related to the effective local work function of the material [15]. This exponential dependence is the source of STM's remarkable vertical sensitivity, as a change in tip-sample distance of merely 1 Å can alter the tunneling current by an order of magnitude [15]. For a typical STM operating with a tunneling current of 1 nA, the tip-sample distance is maintained in the range of 4-7 Å (0.4-0.7 nm) [6].

Core STM Instrumentation

Implementing either constant-current or constant-height mode requires a sophisticated instrumental setup with several critical components:

Scanning Tip: Typically fabricated from tungsten, platinum-iridium, or gold wire through electrochemical etching or mechanical shearing [6]. The ultimate resolution is limited by the radius of curvature of the tip's apex, with ideal tips terminating in a single atom. Tip quality significantly affects image quality, and multiple apexes can cause artifacts such as double-tip imaging [6].

Piezoelectric Scanner: Usually constructed from a radially polarized piezoelectric ceramic tube (often lead zirconate titanate) with a piezoelectric constant of approximately 5 nanometers per volt [6]. The outer surface is divided into four electrodes to enable precise three-dimensional positioning—applying voltages to opposing electrodes causes bending for x-y motion, while voltage applied to the entire tube causes extension or contraction for z-motion [6].

Vibration Isolation System: Essential for maintaining stable tip-sample separation given the extreme sensitivity of tunneling current to distance. Early STMs used magnetic levitation, while modern systems employ mechanical spring or gas spring systems, sometimes supplemented with eddy current damping [6]. Systems designed for long scans or spectroscopy require extreme stability, often being housed in dedicated anechoic chambers with acoustic and electromagnetic isolation [6].

Control Electronics and Feedback System: sophisticated electronics for controlling piezoelectric elements, applying bias voltages, measuring tunneling currents, and implementing feedback loops. The computer system coordinates scanning, data acquisition, and image processing [6].

Constant-Current Imaging Mode

Operational Principle

Constant-current mode is the more widely used STM imaging method, particularly for surfaces with significant topography [1]. In this mode, a feedback loop continuously adjusts the height of the tip above the sample surface to maintain a predetermined, constant tunneling current (setpoint) as the tip rasters across the sample [1] [15]. The feedback mechanism compares the measured tunneling current with the setpoint value at each position; if the current exceeds the setpoint, the feedback system retracts the tip, while if the current is too low, it moves the tip closer to the surface [1]. The voltage applied to the z-scanner piezoelectric element to maintain constant current is recorded and converted into topographical information, creating a three-dimensional height profile of the surface [6] [15].

The resulting image represents a surface of constant tunneling probability, which correlates with both physical topography and local electronic properties of the sample. When the surface is atomically flat, the voltage applied to the z-scanner mainly reflects variations in local charge density. However, when atomic steps or reconstructed surfaces are encountered, the height adjustment incorporates both true topography and electron density effects, making interpretation sometimes ambiguous [6].

Experimental Protocol

Implementing constant-current mode requires careful configuration of several parameters:

Tip Approach: Begin with the tip retracted from the surface. Engage the coarse positioning mechanism to bring the tip within tunneling range (typically monitored visually or through current monitoring). Once within range, fine control is handed over to the piezoelectric scanners [6].

Parameter Setup:

- Set the target tunneling current (setpoint), typically in the sub-nanoampere range [6]

- Select an appropriate bias voltage (typically several millivolts to volts) depending on the sample material

- Configure feedback loop gains (proportional, integral, and sometimes derivative parameters) to ensure stable operation without oscillation

Scan Execution:

- Initiate the raster scan pattern across the desired area

- The feedback system continuously adjusts the z-scanner height at each point to maintain constant current

- Record the z-scanner voltage as a function of (x,y) position

Data Collection:

- The recorded z-position data forms the topographical image

- Additional channels can simultaneously record variations in tunneling current or other parameters

Table: Key Parameters for Constant-Current Mode

| Parameter | Typical Range | Effect on Imaging |

|---|---|---|

| Tunneling Current Setpoint | 0.01-10 nA | Higher currents reduce tip-sample distance, increasing risk of tip crashes but potentially improving signal-to-noise ratio |

| Bias Voltage | Several mV to V | Affects electron tunneling probability and sample interaction; polarity determines direction of electron flow |

| Scan Speed | 0.1-10 Hz (line frequency) | Slower speeds improve stability on rough surfaces but increase acquisition time |

| Feedback Gain | Application-dependent | Higher gains improve response but can cause oscillation; requires optimization for each surface |

Applications and Limitations

Constant-current mode is particularly well-suited for:

- Rough or irregular surfaces where maintaining a safe tip-sample distance is critical [15]

- Atomic-scale defect imaging where precise tracking of surface variations is necessary

- Long-duration experiments where thermal drift or other instabilities might affect tip-sample distance

- Spectroscopy mapping where maintaining constant tip-sample separation is prerequisite for comparable electronic measurements

The primary limitations of constant-current mode include:

- Reduced scan speed due to the response time of the feedback loop [15]

- Potential feedback instability on surfaces with abrupt height changes

- Mixed topographical and electronic information in the resulting images, sometimes complicating interpretation [6]

Constant-Height Imaging Mode

Operational Principle

In constant-height mode, the tip travels at a fixed height above the sample surface while the tunneling current is monitored as the tip scans [1] [15]. Unlike constant-current mode, no feedback adjustment occurs to maintain constant current during the scan line. Instead, the variations in tunneling current resulting from changes in tip-sample separation (due to surface topography) or local electronic structure are directly mapped [6] [15]. This mode capitalizes on the exponential dependence of tunneling current on distance, where minute variations in surface height produce significant changes in current that can be measured with high sensitivity [15].

The constant-height mode image therefore represents a direct mapping of the tunneling current as a function of (x,y) position at approximately constant average tip-sample separation. Since the tunneling current depends both on the actual topography and the local density of states (LDOS) of the sample, the images contain information about both surface structure and electronic properties [6] [1]. For flat surfaces with uniform electronic properties, the current variations directly reflect surface topography, while on heterogeneous surfaces, the interpretation becomes more complex.

Experimental Protocol

Implementing constant-height mode requires distinct experimental considerations:

Surface Assessment: Confirm the sample surface is sufficiently smooth for safe operation in constant-height mode [15]

Initial Setup:

- Approach the tip to tunneling range using standard procedures

- Establish stable tunneling conditions in feedback mode initially

- Disable or greatly reduce the feedback loop response for the fast scan direction

Parameter Selection:

- Set the initial tip height based on a reference tunneling current

- Choose appropriate bias voltage for the specific experiment

- Select scan speed compatible with current amplifier bandwidth

Data Acquisition:

- Maintain constant z-scanner voltage while rastering across the surface

- Record tunneling current variations as a function of (x,y) position

- Potentially record multiple channels simultaneously (current, derivative signals)

Post-Processing:

- Apply necessary filtering to reduce noise in the current signal

- Convert current variations to height information using the known exponential relationship if quantitative topography is desired

Table: Key Parameters for Constant-Height Mode

| Parameter | Typical Range | Effect on Imaging |

|---|---|---|

| Initial Tip-Sample Distance | 4-7 Å | Determines baseline tunneling current and risk of tip crash |

| Bias Voltage | Several mV to V | Influences tunneling probability and surface electronic sensitivity |

| Scan Speed | 1-80 Hz (or higher) | Faster speeds possible due to absent feedback limitations [6] |

| Current Amplifier Bandwidth | Must match scan speed requirements | Higher bandwidth enables faster scanning but may increase noise |

Applications and Limitations

Constant-height mode offers particular advantages for:

- High-speed imaging of dynamic processes, with frame rates up to 80 Hz demonstrated in video-rate STMs [6]

- Atomic-scale resolution on flat surfaces where the exponential current-distance dependence provides exceptional sensitivity [15]

- Electronic structure mapping where the direct current measurement reflects local density of states without feedback interference [1]

- Molecular orbital imaging where frontier orbitals can be visualized with proper bias voltage selection [1]

Significant limitations include:

- Risk of tip damage or sample modification due to possible collisions with surface protrusions [6] [15]

- Restriction to relatively smooth surfaces where height variations are minimal [15]

- Limited usable dynamic range due to the exponential current response to height variations

Comparative Analysis and Technical Considerations

Direct Comparison of Operating Modes

Understanding the relative strengths and limitations of each imaging mode is essential for appropriate selection based on experimental needs. The following table provides a systematic comparison:

Table: Comprehensive Comparison of Constant-Current vs. Constant-Height Modes

| Characteristic | Constant-Current Mode | Constant-Height Mode |

|---|---|---|

| Feedback Loop | Active: maintains constant current by adjusting tip height [1] [15] | Inactive or minimal: tip height fixed during scan line [1] [15] |

| Primary Output Signal | Z-scanner voltage (height adjustment) [15] | Tunneling current variation [15] |

| Scan Speed | Slower (limited by feedback response) [15] | Faster (no feedback limitations) [6] [15] |

| Surface Compatibility | Rough, irregular surfaces with significant topography [15] | Atomically flat surfaces with minimal height variations [15] |

| Risk of Tip Damage | Lower (feedback maintains safe distance) [6] | Higher (possible crashes with protrusions) [6] [15] |

| Information Content | Topography mixed with electronic structure [6] | Direct electronic density mapping with topographical influence [6] |

| Quantitative Height Data | Direct measurement [15] | Indirect (derived from current using exponential relationship) [15] |

| Best Applications | Rough surfaces, defect studies, spectroscopy [15] | Flat surfaces, dynamic processes, electronic structure [6] [15] |

Advanced Applications: Scanning Tunneling Spectroscopy (STS)

A powerful extension of both imaging modes is Scanning Tunneling Spectroscopy (STS), where spectroscopic information is obtained by fixing the tip position and measuring current-voltage (I-V) characteristics [6] [15]. This technique provides detailed information about the local density of states (LDOS) at specific surface locations. STS can be performed in two primary ways:

Point Spectroscopy: The tip is positioned over a feature of interest, the feedback is disabled, and the bias voltage is ramped while measuring current. This provides I-V characteristics at specific locations [6].

Spectroscopy Mapping: A grid of measurement points is defined, and I-V curves are acquired at each point. This creates a three-dimensional map of electronic properties across the surface [15].

STS is particularly valuable for investigating impurities, defects, and nanoscale heterogeneities, as the local density of states at such sites often differs significantly from the surrounding areas [6]. When combined with spatial mapping, STS can reveal how electronic properties vary across a surface, providing insights into quantum confinement, band bending, and other electronically important phenomena.

Research Reagent Solutions and Materials

Successful implementation of STM imaging modes requires specific materials and instrumentation components. The following table details essential items for a functional STM system:

Table: Essential Materials and Components for STM Research

| Component/Reagent | Function/Application | Technical Specifications |

|---|---|---|

| Conductive Tips | Serves as scanning probe for tunneling | Materials: Tungsten, Platinum-Iridium, or Gold [6]; Fabrication: Electrochemical etching (W) or mechanical shearing (Pt-Ir) [6]; Radius: Atomic-scale termination critical for resolution [6] |

| Piezoelectric Scanner | Provides precise tip positioning in 3D | Material: Lead zirconate titanate ceramic [6]; Sensitivity: ~5 nm/V [6]; Configuration: Tubular with quadrant electrodes for x-y motion [6] |

| Vibration Isolation System | Minimizes mechanical noise | Types: Mechanical spring, gas spring, or magnetic levitation systems [6]; Performance: Should achieve better than 0.01 nm stability [6] |

| Current Amplifier | Measures minute tunneling currents | Gain: High gain values for sub-nanoampere currents [15]; Types: Internal, VECA, or ULCA amplifiers with varying noise profiles [15]; Bandwidth: Must support desired scan speeds |

| Sample Substrates | Provides flat, clean surface for deposition | Highly Oriented Pyrolytic Graphite (HOPG) [1]; Single crystal metal surfaces (Au, Cu, Pt) [6]; Preparation: UHV cleavage, annealing, sputtering [6] |

| Bias Voltage Source | Establishes potential for electron tunneling | Range: Millivolts to several volts; Stability: High precision and low noise; Polarity: Reversible (sample or tip positive) |

| UHV System | Maintains pristine surface conditions | Pressure: ≤10⁻¹⁰ mbar for pristine surfaces [6]; Temperature range: From near 0K to over 1000°C possible [6] |

Methodological Workflows

The following diagrams illustrate the fundamental operational workflows for both STM imaging modes, highlighting the critical decision points and signal pathways.

Constant-Current Mode Workflow

Constant-Height Mode Workflow

The choice between constant-current and constant-height imaging modes in Scanning Tunneling Microscopy represents a fundamental trade-off that researchers must optimize based on their specific experimental requirements. Constant-current mode offers greater safety for the tip and sample while accommodating more varied topography, making it ideal for initial surface characterization and rough samples. Constant-height mode provides superior temporal resolution and direct electronic structure mapping, making it invaluable for studying dynamic processes and flat surfaces at the atomic scale.

Both modes continue to enable groundbreaking research in nanotechnology, surface science, and materials characterization. Recent advances in video-rate STM and low-current imaging further expand the capabilities of each mode, pushing the boundaries of spatial and temporal resolution [6] [1]. As STM technology continues to evolve, complemented by techniques such as atomic force microscopy, the fundamental principles of constant-current and constant-height imaging remain essential knowledge for researchers pursuing atomic-scale surface understanding.

From Theory to Lab Bench: Advanced STM Applications in Catalysis and Biomedicine

Scanning Tunneling Microscopy (STM) stands as a pivotal characterization technique in surface science, providing unprecedented atomic-resolution imaging capabilities. The invention of STM by Binnig and Rohrer in 1981 marked a transformative breakthrough in nanotechnology and surface science, enabling the first real-space, atomic-resolution visualization of surface reconstructions such as the Si(111) 7×7 surface [16]. While conventional STM provides static atomic-scale snapshots, operando and in-situ STM techniques have emerged as powerful methodologies for investigating dynamic processes on surfaces under realistic reaction conditions. These advanced approaches enable researchers to monitor surface transformations, identify active sites, and track reaction intermediates in real-time during actual catalytic processes [16] [17].

The fundamental working principle of STM relies on the quantum tunneling effect. When an ultrasharp metal tip approaches a conductive sample surface within approximately 1 nanometer, electrons tunnel through the vacuum potential barrier, generating a measurable tunneling current. This current exhibits exponential dependence on the tip-sample separation, enabling atomic-scale resolution by maintaining a constant current through precision feedback control during scanning [16] [17]. This exquisite sensitivity to electronic and topographic features makes STM uniquely suited for investigating chemical processes at the atomic scale.

Fundamental Principles and Technical Considerations

Core Physical Principles

The quantum mechanical foundation of STM revolves around the tunneling phenomenon, where electrons traverse classically forbidden energy barriers. The tunneling current (I) follows the relationship:

[ I \propto V_b e^{(-A \phi^{1/2} s)} ]

where ( V_b ) represents the bias voltage, ( \phi ) the average work function, ( s ) the tip-sample separation, and ( A ) a constant. This exponential dependence enables STM to achieve sub-ångström vertical resolution and atomic-scale lateral resolution under optimal conditions [16]. The local density of states (LDOS) of the sample surface significantly influences the tunneling current, allowing STM to probe not only topographic features but also electronic structure variations across different surface sites.

Extension to Operando and In-Situ Conditions

Adapting STM for operando and in-situ investigations requires specialized instrumentation to maintain atomic resolution while replicating realistic reaction environments. Electrochemical STM (EC-STM) represents a crucial advancement, enabling atomic-level imaging at the electrode/electrolyte interface during electrochemical processes [17]. This technique incorporates electrochemical cells with STM scanners while maintaining precise potential control over both the working electrode (sample) and the tip, allowing researchers to correlate surface structural changes with applied potential in real time.

For heterogeneous catalysis studies, high-pressure and elevated-temperature STM systems have been developed to bridge the pressure gap between traditional ultra-high vacuum (UHV) STM and industrial reaction conditions. These systems incorporate specialized gas handling capabilities, reaction cells, and temperature control systems to monitor surface transformations during catalytic reactions [16]. The technical challenges include minimizing thermal drift, maintaining tip stability under reactive atmospheres, and ensuring uniform gas exposure while preserving atomic resolution.

Current Applications in Catalysis Research

Heterogeneous Catalysis

Operando STM has revolutionized our understanding of heterogeneous catalytic processes by enabling direct observation of surface dynamics under reaction conditions. Recent studies have employed these techniques to investigate:

- Adsorbate-induced surface restructuring: Metal surfaces often undergo significant reconstruction upon adsorption of reactant molecules. For instance, CO adsorption on Co(0001) surfaces induces the formation of high-coverage CO superstructures that can be directly visualized with atomic precision [16].

- Active site identification: STM enables direct correlation between surface topographic features and catalytic activity. Studies on model catalysts have revealed that undercoordinated sites at step edges, kinks, and defects frequently exhibit enhanced catalytic activity compared to terrace sites [16].

- Surface oxidation and reduction dynamics: The transformation of metal surfaces under oxidizing and reducing environments has been tracked in real-time, revealing the nucleation and growth of oxide phases and their reduction pathways [16].

A notable example includes the investigation of Pd-Fe alloy surfaces, where oxidation induces segregation of FeO to the surface, creating distinct catalytic environments that can be characterized with STM before, during, and after the oxidation process [16].

Electrocatalysis

EC-STM has provided unprecedented insights into electrochemical processes relevant to energy conversion and storage. Key applications include:

- Electrode surface evolution: Monitoring potential-induced reconstruction of electrode surfaces during operation, particularly for processes such as oxygen evolution reaction (OER) and hydrogen evolution reaction (HER) [17].

- Intermediate species identification: Direct imaging of reaction intermediates stabilized at electrode-electrolyte interfaces, providing structural information complementary to spectroscopic data [16].

- Nanostructured catalyst characterization: Atomic-scale imaging of emerging electrocatalysts including single-atom catalysts (SACs), metal clusters, and two-dimensional materials under operational conditions [16].

These investigations have revealed that electrode surfaces are dynamic entities that undergo significant restructuring under potential control, challenging traditional models of static electrode surfaces and highlighting the importance of studying electrocatalysts under working conditions.

Table 1: Quantitative Insights from Operando STM Studies in Catalysis

| Catalytic System | Surface Phenomenon | Spatial Resolution | Temporal Resolution | Key Insight |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CO oxidation on Pd-Fe alloys | Surface segregation | Atomic-scale (sub-Å) | Seconds to minutes | Oxidation induces FeO segregation to surface [16] |

| CO adsorption on Co(0001) | Superstructure formation | Atomic-scale | Minutes | High-coverage CO induces surface reconstruction [16] |

| Electrochemical interfaces | Potential-dependent reconstruction | Atomic-scale | Seconds | Electrode surface structure depends on applied potential [17] |

| Single-atom catalysts | Metal-support interactions | Sub-Ångström | Limited | Stability determined by anchoring sites [16] |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol: Electrochemical STM for CO₂ Reduction Studies

Objective: To characterize the surface reconstruction of copper electrodes during the electrochemical CO₂ reduction reaction (CO₂RR) using in-situ EC-STM.

Materials and Equipment:

- Electrochemical STM system with potentiostat

- Single-crystal copper working electrode

- Platinum counter electrode

- Reversible hydrogen reference electrode (RHE) or appropriate alternative

- CO₂-saturated electrolyte (0.1M KHCO₃)

- Purification materials for electrolyte (e.g., activated alumina)

- STM tips: Electrodynamically etched tungsten or Pt/Ir wires

Procedure:

Tip Preparation:

- Electrochemically etch tungsten wire in 2M NaOH solution using alternating current (5-10 V AC)

- Apply appropriate insulation (apiezon wax or electrophoretic paint) to minimize faradaic currents

- Characterize tip quality by approach to a test surface (e.g., HOPG) in air

Electrode Preparation:

- Prepare single-crystal Cu electrode by repeated cycles of mechanical polishing, electrochemical polishing, and annealing

- Confirm surface quality and cleanliness by cyclic voltammetry in sulfate-containing solution

- Transfer to STM cell under protective atmosphere to prevent oxidation

EC-STM Cell Assembly:

- Assemble electrochemical cell with the prepared Cu working electrode

- Position reference and counter electrodes to minimize uncompensated resistance

- Introduce CO₂-saturated electrolyte under inert atmosphere

- Ensure proper sealing to exclude oxygen during measurements

In-Situ Imaging:

- Approach tip to the electrode surface under potential control (e.g., -0.2 V vs. RHE)

- Acquire baseline images of the initial surface structure

- Step the potential to CO₂RR conditions (typically -0.6 to -1.0 V vs. RHE)

- Continuously monitor surface changes with time-lapse STM imaging

- Correlate structural changes with simultaneously recorded electrochemical data

Data Analysis:

- Process raw STM images to correct for thermal drift and scanner distortions

- Quantify surface roughness, step density, and defect formation as functions of time and potential

- Correlate structural features with reaction selectivity (e.g., hydrocarbon vs. CO production)

Troubleshooting:

- If unstable tunneling occurs, verify tip insulation and purity of electrolyte

- If surface contamination is suspected, repeat electrode preparation with stricter cleanliness protocols

- For poor image quality at CO₂RR potentials, optimize tip shielding and vibration isolation

Protocol: High-Pressure STM for Heterogeneous Catalysis

Objective: To visualize the dynamics of active sites on catalyst surfaces during heterogenous catalytic reactions (e.g., CO oxidation) under operando conditions.

Materials and Equipment:

- High-pressure STM system with reaction cell

- Model catalyst sample (e.g., single crystal metal surface)

- High-purity reaction gases (CO, O₂)

- Gas handling system with pressure control and purification

- Mass spectrometer for gas analysis (optional but recommended)

- STM tips: W or Pt/Ir suitable for high-pressure operation

Procedure:

Sample Preparation:

- Clean single crystal surface by repeated sputtering-annealing cycles in UHV

- Verify surface cleanliness and order by UHV-STM and AES

- Transfer sample to high-pressure cell without breaking vacuum

Reaction Conditions Setup:

- Introduce reaction mixture (e.g., 1:2 CO:O₂ ratio) to desired pressure (typically mbar range)

- Heat sample to reaction temperature (e.g., 300-500 K for CO oxidation)

- Allow system to stabilize before beginning imaging

Operando Imaging:

- Acquire time-lapse STM images of the same surface region throughout the reaction

- Monitor changes in surface structure, island formation, and step mobility

- Correlate surface dynamics with catalytic activity (via simultaneous gas analysis if available)

- Systematically vary pressure and temperature to study their effects on surface processes

Post-Reaction Analysis:

- Pump out reaction gases and return to UHV conditions

- Characterize the post-reaction surface structure with high-resolution STM

- Perform additional surface analysis (XPS, AES) to determine composition changes

Safety Considerations:

- Implement proper gas handling procedures for reactive mixtures

- Include pressure relief safety mechanisms in high-pressure cell design

- Plan for safe disposal of reaction products

Research Reagent Solutions and Essential Materials

Table 2: Essential Research Materials for Operando and In-Situ STM

| Material/Reagent | Specification | Function/Application | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Single crystal surfaces | Metal foils (Pt, Au, Cu, Pd) with specific crystallographic orientation | Well-defined model catalysts for fundamental studies | Surface orientation determines reactivity; purity >99.999% |

| STM tip materials | Tungsten (W) or Platinum-Iridium (Pt/Ir) wires | Nanoscale probe for tunneling current | Tip sharpness determines resolution; requires proper insulation for liquid environments |

| Electrolytes | High-purity salts (KCl, KHCO₃, H₂SO₄) and ultrapure water | Ionic conduction in electrochemical cells | Must be purified to eliminate contaminants; degassed to remove oxygen |

| Reaction gases | High-purity CO, O₂, H₂ with purification filters | Reactants for catalytic studies | Purification essential to remove contaminants that poison surfaces |

| Reference electrodes | Reversible Hydrogen Electrode (RHE), Ag/AgCl | Potential control and measurement in electrochemical systems | Requires careful calibration and maintenance |

| Insulation materials | Apiezon wax, electrophoretic paint | Tip insulation to reduce faradaic currents in EC-STM | Must be stable under experimental conditions |

| Calibration samples | Highly Oriented Pyrolytic Graphite (HOPG), Au(111) | Scanner calibration and tip characterization | Atomically flat surfaces with known periodicities |

Visualization of Operando STM Workflows

Operando STM Experimental Workflow: This diagram illustrates the integrated workflow for operando STM investigations, highlighting the critical steps from sample preparation through data analysis to atomic-scale insight generation.

Operando and in-situ STM techniques have fundamentally transformed our approach to investigating surface reactions by providing direct atomic-scale visualization of dynamic processes under realistic conditions. These methodologies have enabled unprecedented insights into catalytic mechanisms, electrode evolution, and nanoscale materials behavior that were previously inaccessible through conventional ex situ characterization approaches [16] [17].