Benchmarking Surface Analysis Methods: A 2025 Guide for Pharmaceutical and Biomedical Research

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on benchmarking surface analysis techniques critical for pharmaceutical innovation.

Benchmarking Surface Analysis Methods: A 2025 Guide for Pharmaceutical and Biomedical Research

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on benchmarking surface analysis techniques critical for pharmaceutical innovation. It explores foundational principles, methodological applications for drug delivery systems and nanomaterials, troubleshooting for complex samples, and validation frameworks adhering to regulatory standards. By synthesizing current market trends, technological advancements, and standardized protocols, this resource enables scientists to select optimal characterization strategies that enhance drug bioavailability, ensure product quality, and accelerate therapeutic development.

Surface Analysis Fundamentals: Core Techniques and Industry Growth Drivers in Pharmaceutical Research

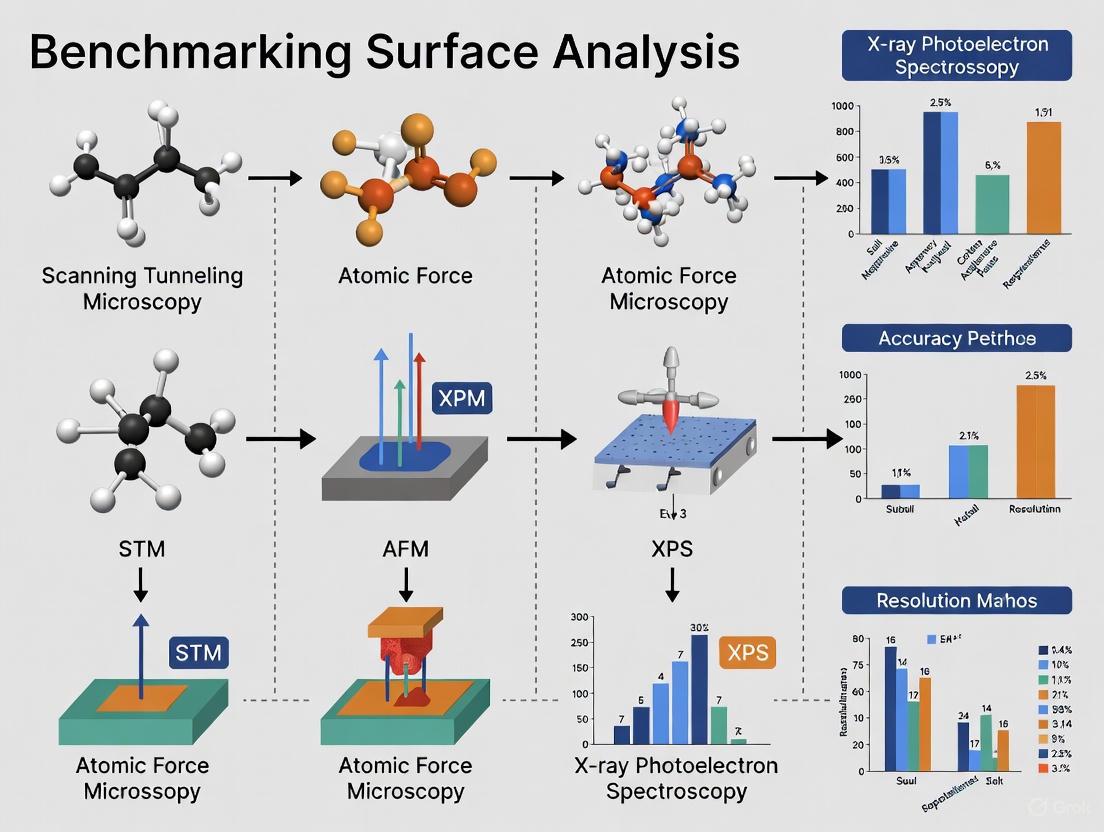

Surface analysis is a critical discipline in modern scientific research and industrial development, enabling the detailed characterization of material properties at the atomic and molecular levels. For researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, selecting the appropriate analytical technique is paramount for obtaining accurate, relevant data. This guide provides a comprehensive comparison of four cornerstone techniques—Scanning Tunneling Microscopy (STM), Atomic Force Microscopy (AFM), X-ray Photoelectron Spectroscopy (XPS), and Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM)—by examining their fundamental principles, distinct capabilities, and experimental applications. The objective benchmarking presented here supports informed methodological decisions in both research and development contexts, particularly as the surface analysis market continues to evolve with advancements in technology and increasing demand from sectors such as semiconductors, materials science, and biotechnology [1] [2].

Core Principles and Technical Specifications

The operational fundamentals of each technique dictate its specific applications and limitations. The following table provides a comparative overview of these key characteristics.

Table 1: Comparative Overview of Surface Analysis Techniques

| Technique | Fundamental Principle | Primary Information Obtained | Spatial Resolution | Sample Requirements |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| STM | Quantum tunneling of electrons between a sharp tip and a conductive surface [3] [4] | Topography & electronic structure (LDOS*) [4] [5] | Atomic/sub-atomic [4] [6] | Conductive or semi-conductive surfaces [3] |

| AFM | Mechanical force sensing between a sharp tip and the surface [3] [5] | 3D topography, mechanical properties (e.g., adhesion, stiffness) [3] [7] | Sub-nanometer (atomic possible) [3] | All surfaces (conductive and insulating) [3] [5] |

| XPS | Photoelectric effect: emission of core-level electrons by X-ray irradiation [1] | Elemental composition, chemical state, electronic state [1] | ~3-10 µm [1] | Solid surfaces under ultra-high vacuum (UHV); minimal sample charging |

| SEM | Interaction of focused electron beam with sample, emitting secondary electrons [1] | Surface morphology, topography, composition (with EDX) [1] | ~0.5-10 nm [1] | Solid surfaces; often requires conductive coating for insulating samples |

LDOS: Local Density of States; *EDX: Energy-Dispersive X-ray Spectroscopy*

Operational Modes and Data Acquisition

Each technique employs specific operational modes to extract different types of data.

STM Modes:

- Constant Current Mode: The tip height is adjusted to maintain a constant tunneling current, providing topographic information [5].

- Constant Height Mode: The tip travels at a fixed height while the variation in tunneling current is recorded, allowing for faster scanning [5].

- Scanning Tunneling Spectroscopy (STS): The tunneling current is measured as a function of the applied bias voltage at a specific location, revealing the local electronic density of states (LDOS) on the surface [3] [4].

AFM Modes:

- Contact Mode: The tip is dragged across the surface while maintaining constant deflection, providing high resolution but potentially causing damage to soft samples [3].

- Tapping Mode: The cantilever is oscillated at its resonance frequency to lightly "tap" the surface, reducing lateral forces and minimizing sample damage [3].

- Non-Contact Mode: The cantilever oscillates above the sample surface without making contact, used for delicate or liquid-immersed samples, though with lower resolution [3].

XPS Technique: This method is typically performed in a single analytical mode but provides deep chemical information by measuring the kinetic energy of ejected photoelectrons, which is characteristic of specific elements and their chemical bonding environments [1].

SEM Techniques:

Experimental Protocols and Benchmarking Data

To ensure reproducible and reliable results, standardized experimental protocols are essential. This section outlines general methodologies for each technique and presents comparative benchmarking data.

Detailed Methodologies

Protocol 1: Atomic-Scale Surface Characterization via STM

- Sample Preparation: A conductive sample (e.g., metal single crystal, highly oriented pyrolytic graphite - HOPG) is cleaned through repeated cycles of sputtering (e.g., with Ar⁺ ions) and annealing in an ultra-high vacuum (UHV) chamber to obtain an atomically clean and well-ordered surface [4].

- Tip Preparation: An electrochemically etched tungsten or platinum-iridium wire is used to create an atomically sharp tip [4].

- System Calibration: The STM scanner is calibrated using a standard sample with a known atomic lattice (e.g., graphite (HOPG) or Si(111)-(7x7) reconstruction) [4].

- Approach and Engagement: The tip is brought into proximity with the surface (typically <1 nm) using coarse motor controls, followed by a fine piezoelectric approach until a stable tunneling current (e.g., 0.1-5 nA) is established with a applied bias voltage (e.g., 10 mV - 2 V) [4] [5].

- Imaging/Spectroscopy:

Protocol 2: Nanoscale Topography and Mechanical Property Mapping via AFM

- Sample Mounting: The sample (can be insulator or conductor) is securely fixed onto a magnetic or adhesive sample disk.

- Tip/Cantilever Selection: Choose an appropriate cantilever based on the sample and mode:

- Contact Mode: A stiff cantilever (e.g., silicon nitride).

- Tapping Mode: A cantilever with a resonant frequency of 100-400 kHz [3].

- Engagement: The tip is approached to the surface until the system detects a change in the laser position on the photodetector, indicating contact or interaction with the surface [3] [5].

- Scanning and Data Acquisition:

- Set scanning parameters (e.g., scan size, rate, and setpoint).

- For force measurements, perform force-distance curves by extending and retracting the tip at a specific location to quantify adhesion forces and sample elasticity [3].

Protocol 3: Elemental and Chemical State Analysis via XPS

- Sample Preparation: A solid sample is mounted on a holder, often using conductive tape. Non-conductive samples may require charge neutralization with an electron flood gun [1].

- Load into UHV: The sample is introduced into an ultra-high vacuum chamber (pressure < 10⁻⁸ mbar) to minimize surface contamination and allow electron detection without scattering [1].

- Data Acquisition:

- A survey spectrum is acquired over a wide energy range (e.g., 0-1200 eV binding energy) to identify all elements present.

- High-resolution spectra are then collected for specific elemental regions to determine chemical states.

- Data Analysis: Spectra are analyzed using specialized software, which involves background subtraction, peak fitting, and comparing binding energies to standard databases [1].

Protocol 4: High-Resolution Surface Morphology Imaging via SEM

- Sample Preparation: The sample is secured to a stub with conductive tape. If the sample is insulating, a thin conductive coating (e.g., gold, platinum, or carbon) is applied via sputter coating to prevent charging [1].

- Load into Vacuum Chamber: The sample is placed in the SEM sample chamber, which is then evacuated.

- Microscope Alignment: The electron column is aligned, and the working distance is selected.

- Imaging: The beam energy (accelerating voltage) and current are selected. The beam is focused, and stigmation is corrected. Images are captured using a secondary electron detector for topography or a backscattered electron detector for compositional contrast [1].

Performance Benchmarking and Experimental Data

The capabilities of these techniques are often complementary. The following table summarizes key performance metrics and representative experimental data obtained from each method.

Table 2: Performance Benchmarking and Representative Data

| Technique | Key Measurable Parameters | Representative Experimental Data Output | Typical Experimental Timeframe |

|---|---|---|---|

| STM | Surface roughness, atomic periodicity, defect density, LDOS [4] [5] | Atomic-resolution images of reconstructions (e.g., Si(111)-7x7); real-space visualization of molecular adsorbates [4] | Minutes to hours for atomic-resolution imaging [4] |

| AFM | Surface roughness, step heights, particle size, modulus, adhesion force, friction [3] [8] | 3D topographic maps of polymers, biomolecules; force-distance curves quantifying adhesion [3] [7] | Minutes for a single topographic image |

| XPS | Atomic concentration (%), chemical state identification (peak position), layer thickness (via angle-resolved measurements) [1] | Survey spectrum showing elemental composition; high-resolution C 1s spectrum revealing C-C, C-O, O-C=O bonds [1] | Minutes for a survey scan; hours for detailed mapping |

| SEM | Particle size distribution, grain size, layer thickness, surface porosity, elemental composition (with EDX) [1] | High-resolution micrographs of micro/nanostructures; false-color EDX maps showing elemental distribution [1] | Seconds to minutes per image |

Application Scenarios and Workflow Integration

Understanding the optimal use cases for each technique allows for effective experimental design and workflow integration in research and development.

Technique Selection Guide

The decision on which technique to use is driven by the specific scientific question.

Choosing STM: Ideal for investigating electronic properties and atomic-scale surface structures of conductive materials. It is indispensable in catalysis research for identifying active sites and in materials science for studying 2D materials like graphene [4] [6]. Its requirement for conductive samples and UHV conditions can be a limitation [3].

Choosing AFM: The preferred method for obtaining three-dimensional topography and for measuring nanomechanical properties (e.g., stiffness, adhesion) across any material type. It is widely used in biology for imaging cells and biomolecules, in polymer science, and for quality control in thin-film coatings [3] [5]. Its key advantage is the ability to operate in various environments, including ambient air and liquid [3].

Choosing XPS: The definitive technique for determining surface elemental composition and chemical bonding states. It is critical for studying surface contamination, catalyst deactivation, corrosion layers, and the functional groups on polymer surfaces [1]. Its main limitations are its relatively poor spatial resolution compared to probe microscopy and the requirement for UHV [1].

Choosing SEM: Best suited for rapid high-resolution imaging of surface morphology over a large range of magnifications. It provides a pseudo-3D appearance that is intuitive to interpret. It is a workhorse in failure analysis, nanomaterials characterization, and biological imaging [1]. When equipped with an EDX detector, it can provide simultaneous elemental analysis [1].

Workflow Visualization: Selecting a Surface Analysis Technique

The following diagram outlines a logical decision workflow for selecting the most appropriate surface analysis technique based on the primary research goal.

Diagram 1: Technique selection workflow based on primary analysis need and sample properties.

Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Successful surface analysis requires not only sophisticated instrumentation but also a suite of specialized consumables and materials.

Table 3: Key Research Reagents and Materials for Surface Analysis

| Item | Function/Application | Common Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Conductive Substrates | Provides a flat, clean, and conductive surface for depositing samples for STM, AFM, or as a base for SEM. | Highly Oriented Pyrolytic Graphite (HOPG), Silicon wafers (often with a conductive coating), Gold films on mica [4]. |

| Sputter Coaters / Conductive Coatings | Applied to non-conductive samples for SEM analysis to prevent charging and to improve secondary electron emission. | Gold/Palladium (Au/Pd), Platinum (Pt), Carbon (C) coatings applied via sputter coating or evaporation [1]. |

| AFM Probes (Cantilevers) | The sensing element in AFM; different types are required for different modes and samples. | Silicon nitride tips for contact mode in liquid; sharp silicon tips for tapping mode; colloidal probes for force spectroscopy [3] [5]. |

| STM Tips | The sensing element in STM; must be atomically sharp and conductive. | Electrochemically etched tungsten (W) wire; mechanically cut Platinum-Iridium (Pt-Ir) wire [4]. |

| Calibration Standards | Used to verify the spatial and dimensional accuracy of the microscope. | Gratings with known pitch (for AFM/SEM), HOPG with 0.246 nm atomic lattice (for STM), certified step height standards [4]. |

| UHV Components | Essential for maintaining the pristine environment required for XPS and most STM experiments. | Ion sputter guns (for sample cleaning), electron flood guns (for charge neutralization in XPS), load-lock systems [1] [4]. |

Emerging Trends and Future Outlook

The field of surface analysis is dynamic, with several trends shaping its future. The integration of artificial intelligence (AI) and machine learning is enhancing data interpretation and automation, leading to faster and more precise analysis [1] [6]. There is a growing emphasis on in-situ and operando characterization, where techniques like STM and AFM are used to observe surface processes in real-time under realistic conditions (e.g., in gas or liquid environments), which is crucial for understanding catalysis and electrochemical interfaces [4] [7]. Furthermore, the push for multi-modal analysis, combining two or more techniques, is providing a more holistic view of surface properties. For instance, combined STM-AFM instruments can simultaneously map electronic and mechanical properties at the molecular scale [7]. These advancements, driven by the demands of the semiconductor, energy storage, and pharmaceutical industries, ensure that these foundational techniques will continue to be indispensable tools for scientific discovery and innovation.

The global surface analysis market is undergoing a significant transformation, driven by technological advancements and increasing demand across research and industrial sectors. This market, essential for characterizing material properties at atomic and molecular levels, is projected to grow from USD 6.45 billion in 2025 to USD 9.19 billion by 2032, exhibiting a compound annual growth rate (CAGR) of 5.18% [6] [2]. This growth is fueled by the critical need to understand surface interactions in material development, semiconductor fabrication, and pharmaceutical research, where surface properties directly influence performance, reliability, and efficacy [9] [10].

For researchers and drug development professionals, selecting appropriate surface analysis techniques is paramount for accurate characterization. This guide provides a comparative analysis of major surface analysis methodologies, supported by experimental data and protocols, to inform strategic decisions in research planning and equipment investment through 2032.

The surface analysis market is characterized by diverse technologies serving multiple high-growth industries. Regional dynamics reveal North America leading with a 37.5% market share in 2025, while the Asia-Pacific region is projected to be the fastest-growing, capturing 23.5% of the market and expanding rapidly due to industrialization and government-supported innovation initiatives [6]. This growth is further propelled by integration of artificial intelligence and machine learning for data interpretation, enhancing precision and efficiency in surface characterization [6].

Table 1: Global Surface Analysis Market Projections (2025-2032)

| Metric | 2025 Value | 2032 Projection | CAGR | Key Drivers |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Market Size | USD 6.45 Billion [6] [2] | USD 9.19 Billion [6] [2] | 5.18% [6] [2] | Semiconductor miniaturization, material innovation, pharmaceutical quality control |

| Leading Technique (Share) | Scanning Tunneling Microscopy (29.6%) [6] | - | - | Unparalleled atomic-scale resolution |

| Leading Application (Share) | Material Science (23.8%) [6] | - | - | Development of advanced materials with tailored properties |

| Leading End-use Industry (Share) | Semiconductors (29.7%) [6] | - | - | Demand for miniaturized, high-performance electronics |

Segment Performance Insights

By Technique: Scanning Tunneling Microscopy (STM) dominates the technique segment due to its unparalleled capability for atomic-scale surface characterization of conductive materials [6]. Other significant techniques include Atomic Force Microscopy (AFM), X-ray Photoelectron Spectroscopy (XPS), and Secondary Ion Mass Spectrometry (SIMS), each with distinct advantages for specific applications.

By Application: The materials science segment leads applications, capturing nearly a quarter of the market share, as surface analysis forms the foundation for understanding structure-property relationships critical for developing advanced alloys, composites, and thin films [6].

By End-use Industry: The semiconductor industry represents the largest end-use segment, driven by escalating demand for miniaturized, high-performance electronic devices requiring precise control over surface and interface properties at nanometer scales [6].

Comparative Analysis of Key Surface Analysis Techniques

Selecting the appropriate surface analysis technique requires understanding their fundamental principles, capabilities, and limitations. The following section provides a comparative assessment of major technologies, with experimental data to guide selection for specific research applications.

Table 2: Technique Comparison for Surface Analysis

| Technique | Resolution | Information Obtained | Sample Requirements | Primary Pharmaceutical Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Scanning Tunneling Microscopy (STM) | Atomic-scale (0.1 nm lateral) [6] | Surface topography, electronic structure [6] | Conductive surfaces [6] | Limited due to conductivity requirement |

| Atomic Force Microscopy (AFM) | Sub-nanometer [11] | 3D surface topography, mechanical properties [11] | Any solid surface [11] | Tablet surface roughness, coating uniformity, particle size distribution [10] |

| X-ray Photoelectron Spectroscopy (XPS) | 10 μm [12] | Elemental composition, chemical state, empirical formula [9] [10] | Solid surfaces, vacuum compatible [9] | Cleanliness validation, contamination identification, coating composition [10] |

| Time-of-Flight SIMS (ToFSIMS) | ~1 μm [10] | Elemental/molecular surface composition, chemical mapping [10] | Solid surfaces, vacuum compatible [9] | Drug distribution mapping, contamination analysis, defect characterization [10] |

Experimental Protocol: Assessing Drug Distribution in Coated Stents

Background: Surface analysis is crucial for optimizing drug-eluting stents, where uniform drug distribution ensures consistent therapeutic release [10].

Objective: To characterize the distribution and thickness of a drug-polymer coating on a coronary stent using multiple surface analysis techniques.

Methodology:

- Sample Preparation: Mount stent segments without alteration for ToFSIMS analysis. For cross-sectional analysis, embed some segments in epoxy resin and section with a microtome [10].

- ToFSIMS Imaging: Acquire high-resolution chemical maps of the stent surface using a ToFSIMS instrument.

- Primary ion beam: Bi³⁺ or Auₙ⁺ clusters for enhanced secondary ion yield

- Analysis area: 500 × 500 μm

- Spatial resolution: ~1 μm

- Detect characteristic secondary ions from the drug compound and polymer matrix [10]

- 3D Profiling: For selected samples, perform sequential ToFSIMS analysis with sputter depth profiling using a C₆₀⁺ or argon cluster ion source to remove thin layers of material between analyses, building a 3D chemical distribution map [10].

- Data Analysis: Process chemical maps to determine the homogeneity of drug distribution and interface width between coating layers.

Expected Outcomes: This protocol enables visualization of drug distribution homogeneity and identification of potential defects in the coating that could affect drug release kinetics [10].

Diagram 1: Workflow for stent coating analysis. This multi-modal approach ensures comprehensive characterization of drug distribution and coating integrity.

Experimental Protocol: Response Surface Methodology for Drug Combination Synergy

Background: Quantitative evaluation of how drugs combine to elicit biological responses is crucial for combination therapy development [13].

Objective: To employ Response Surface Methodology (RSM) for robust quantification of drug interactions, overcoming limitations of traditional index-based methods like Combination Index (CI) and Bliss Independence, which are known to be biased and unstable [13].

Methodology:

- Experimental Design:

- Prepare a matrix of drug concentration combinations covering the anticipated active range

- Include 4-6 concentrations of each drug in a full factorial or central composite design

- Include appropriate controls and replicates

Data Acquisition:

- Expose target cells (e.g., cancer cell lines) to each drug combination

- Measure response (e.g., cell viability) using standardized assays (MTT, CellTiter-Glo)

- Conduct experiments in triplicate to ensure statistical reliability

Response Surface Modeling:

- Fit data to a response surface model (e.g., BRAID model) using nonlinear regression

- The general form for a two-drug combination: where E is the effect, E₀ is baseline effect, E_max is maximum effect, A and B are drug concentrations, EC50 values are potencies, H values are Hill slopes, and α is the interaction parameter [13]

- Calculate synergy scores based on deviation from Loewe additivity reference model

Model Validation:

- Use goodness-of-fit measures (R², AIC) to assess model quality

- Perform residual analysis to check for systematic fitting errors

- Validate predictions with additional experimental points not used in model fitting

Expected Outcomes: RSM provides a complete representation of combination behavior across all dose levels, offering greater stability and mechanistic insight compared to index methods. In comparative studies, RSMs have demonstrated superior performance in clustering compounds by their known mechanisms of action [13].

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Successful surface analysis requires specific materials and reagents tailored to each technique and application. The following table outlines essential solutions for pharmaceutical surface characterization.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Surface Analysis

| Reagent/Material | Function | Application Example | Technical Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Conductive Substrates | Provides flat, conductive surface for analysis of non-conductive materials | AFM/STM of drug particles [10] | Silicon wafers with thin metal coatings (gold, platinum) |

| Cluster Ion Sources | Enables molecular depth profiling of organic materials | SIMS analysis of polymer-drug coatings [10] | C₆₀⁺, Argan clusters, or water cluster ions minimize damage |

| Certified Reference Materials | Instrument calibration and method validation | Quantitative XPS analysis [6] | NIST-traceable standards with certified composition |

| Ultra-high Vacuum Compatible Adhesives | Sample mounting without outgassing | Preparation of tablets for XPS/ToFSIMS [9] | Double-sided carbon or copper tapes; conductive epoxies |

| Charge Neutralization Systems | Mitigates charging effects on insulating samples | XPS analysis of pharmaceutical powders [10] | Low-energy electron floods or charge compensation algorithms |

Future Outlook and Strategic Recommendations

The surface analysis market shows promising growth trajectories with several emerging trends shaping its future development. The integration of AI and machine learning for data interpretation is enhancing precision and efficiency, fueling market expansion [6]. Additionally, sustainability initiatives are prompting more thorough surface evaluations to develop eco-friendly materials, further contributing to the sector's growth trajectory [6].

For research professionals, several strategic considerations emerge:

Technique Selection: Prioritize techniques that offer the spatial resolution and chemical specificity required for your specific applications, considering that multimodal approaches often provide the most comprehensive insights [10].

Automation Investment: Leverage growing capabilities in automated sample analysis and data interpretation to enhance throughput and reproducibility, particularly for high-volume applications like pharmaceutical quality control [6].

Emerging Applications: Monitor developments in nanotechnology, biomedical engineering, and sustainable materials, as these fields are driving innovation in surface analysis capabilities [11].

The continued advancement of surface analysis technologies promises enhanced capabilities for characterizing increasingly complex materials and biological systems, supporting innovation across pharmaceutical development, materials science, and semiconductor manufacturing through the 2025-2032 forecast period and beyond.

Surface analysis technologies stand at the confluence of three powerful industry drivers: the relentless advancement of semiconductor technology, the innovative application of nanotechnology, and an increasingly complex global regulatory landscape. These fields collectively push the boundaries of what is possible in materials characterization, demanding higher precision, greater throughput, and more reproducible data. The semiconductor industry's pursuit of miniaturization, exemplified by the demand for control over surface and interface properties at the nanometer scale, directly fuels innovation in analytical techniques [6]. Simultaneously, nanotechnology applications—particularly in targeted drug delivery—require sophisticated methods to characterize interactions at the bio-nano interface [14] [15]. Framing this progress is a stringent regulatory environment that mandates rigorous standardization and documentation, ensuring that technological advancements translate safely and effectively into commercial products. This guide objectively benchmarks current surface analysis methodologies, providing experimental data and protocols to inform researchers navigating these critical domains.

Industry Landscape and Quantitative Market Drivers

The surface analysis market is experiencing significant growth, propelled by demands from its key end-use industries. The following tables quantify this landscape, highlighting the techniques, applications, and regional markets that are leading this expansion.

Table 1: Global Surface Analysis Market Size and Growth (2025-2032)

| Metric | Value |

|---|---|

| 2025 Market Size | USD 6.45 Billion |

| 2032 Projected Market Size | USD 9.19 Billion |

| Compound Annual Growth Rate (CAGR) | 5.18% [6] |

Table 2: Surface Analysis Market Share by Segment (2025)

| Segment Category | Leading Segment | 2025 Market Share |

|---|---|---|

| Technique | Scanning Tunneling Microscopy (STM) | 29.6% [6] |

| Application | Material Science | 23.8% [6] |

| End-use Industry | Semiconductors | 29.7% [6] |

| Region | North America | 37.5% [6] |

The dominance of STM is attributed to its unparalleled capability for atomic-scale surface characterization of conductive materials, a critical need in advanced materials development [6]. The Asia Pacific region is projected to be the fastest-growing market, driven by high industrialization, massive electronics production capacity, and significant government research budgets in China, Japan, and South Korea [6].

Benchmarking Surface Analysis Techniques

To meet the demands of modern industry, surface analysis methods must be rigorously compared. The table below benchmarks several key technologies, with a special focus on Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR) due to its high-information content and growing adoption in regulated environments like drug development.

Table 3: Performance Benchmarking of Surface Analysis Techniques

| Technique | Key Principle | Optimal Resolution | Primary Applications | Key Advantages | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR) | Detects changes in refractive index at a sensor surface [14]. | ~pg/mm² mass concentration [14]. | Biomolecular interaction analysis, drug release kinetics, antibody screening [14] [16] [15]. | Label-free, real-time kinetic data, suitable for diverse analytes from small molecules to cells [14]. | Mass transfer limitations for large analytes like nanoparticles; requires specific sensor chips [14]. |

| Scanning Tunneling Microscopy (STM) | Measures quantum tunneling current between a sharp tip and a conductive surface [6]. | Atomic-level [6]. | Atomic-scale surface topography and electronic characterization of conductive materials [6]. | Unmatched atomic-resolution imaging [6]. | Requires conductive samples; generally limited to ultra-high vacuum conditions. |

| Atomic Force Microscopy (AFM) | Measures forces between a mechanical probe and the sample surface. | Sub-nanometer. | Surface morphology, roughness, and mechanical properties of diverse materials [6]. | Works on conductive and non-conductive samples in various environments (air, liquid). | Slower scan speeds compared to electron microscopy; potential for tip-sample damage. |

| X-ray Photoelectron Spectroscopy (XPS) | Measures the kinetic energy of photoelectrons ejected by an X-ray source. | ~10 µm; surface-sensitive (top 1-10 nm). | Elemental composition, empirical formula, and chemical state of surfaces [6]. | Quantitative elemental surface analysis and chemical bonding information. | Requires ultra-high vacuum; large area analysis relative to some probes. |

Experimental Protocol: SPR for Drug Release Kinetics

SPR is emerging as a powerful tool for characterizing the release kinetics of drugs from nanocarriers, a critical quality attribute in nanomedicine development [15]. The following provides a detailed methodology.

1. Sensor Chip Preparation:

- Chip Selection: For nanoparticle analytes, a C1 chip (flat, 2D surface) is often preferable to a CM5 chip (3D dextran matrix) to prevent steric hindrance and access all immobilized ligands, though it may increase non-specific binding [14].

- Ligand Immobilization: The chip surface is functionalized with a target molecule (e.g., a receptor or protein relevant to the drug's mechanism). This is typically done via covalent chemistry, such as EDC/NHS amine coupling, to create a stable surface [14] [15]. Immobilization levels are set in Resonance Units (RU) to ensure a measurable signal.

- Physiological Relevance: The density of the immobilized ligand should be optimized to correspond to physiologic densities on target cells and tissues, giving the experiment greater biological meaning [14].

2. Sample Immobilization for Release Studies:

- For drug release studies, the polymer-drug conjugate (nanocarrier) is first captured on the sensor chip. In one documented protocol, this is achieved by conjugating biotin to the polymer carrier and exploiting the strong streptavidin-biotin interaction on a streptavidin-coated chip [15].

- A baseline signal is established with a continuous flow of buffer (e.g., at pH 7.4 to simulate bloodstream conditions) [15].

3. Triggering and Measuring Drug Release:

- The buffer conditions are changed to trigger drug release (e.g., switching to a lower pH buffer, such as pH 5.0, to simulate the acidic environment of a tumor or cellular endosome) [15].

- The dissociation of the drug molecule from the polymer carrier on the chip surface leads to a decrease in mass, which is detected in real-time as a drop in RU [14] [15].

- The rate and extent of this signal change provide direct quantitative data on drug release kinetics.

4. Data Analysis:

- The real-time sensorgram (RU vs. time plot) is analyzed to determine kinetic rate constants (association rate,

kon, and dissociation rate,koff) and the equilibrium dissociation constant (KD) [14]. - For release studies, the data quantifies the rate of drug release under specific environmental stimuli [15].

Figure 1: SPR Drug Release Workflow. This diagram outlines the key steps in using Surface Plasmon Resonance to study the release kinetics of drugs from polymer nanocarriers, as applied in nanomedicine development [14] [15].

The Regulatory Compliance Framework

The semiconductor and nanotechnology industries operate within a strict global regulatory framework that directly influences manufacturing and product development.

Table 4: Key Global Regulatory Standards and Their Impact

| Regulation / Standard | Region | Core Focus | Impact on Industry & Analysis |

|---|---|---|---|

| REACH | European Union | Registration, Evaluation, Authorisation and Restriction of Chemicals [17]. | Mandates transparency in chemical compositions, restricting substances posing environmental/health risks. Increases production costs and documentation [17]. |

| RoHS | European Union | Restriction of Hazardous Substances in electrical and electronic equipment [17]. | Requires manufacturers to reformulate materials and implement stringent testing to ensure components meet safety standards [17]. |

| TSCA | United States | Toxic Substances Control Act [17]. | Regulates the introduction of new or existing chemicals, ensuring safety and compliance. |

| WEEE | European Union | Waste Electrical and Electronic Equipment Directive [17]. | Sets recycling and recovery targets, influencing semiconductor manufacturers to design for recyclability [17]. |

| ISO 9001 | International | Quality Management Systems [17]. | Standardizes manufacturing processes and ensures consistency in semiconductor production [17]. |

| ISO 14001 | International | Environmental Management Systems [17]. | Provides a framework for organizations to continually improve their environmental performance [17]. |

| AS6081 | International | Fraudulent/Counterfeit Electronic Parts Risk Mitigation [17]. | Provides uniform requirements for distributing against counterfeit parts in the military and aerospace supply chains [17]. |

Regulatory compliance has become a critical hurdle, with a recent poll indicating it as the most significant factor for the semiconductor industry to manage in 2025 [17]. Furthermore, government actions, such as shutdowns, can freeze contracting and export licensing from agencies like the Bureau of Industry and Security (BIS), directly delaying shipments of critical materials and disrupting R&D projects funded under acts like the CHIPS Act [18].

Figure 2: Semiconductor Regulatory Compliance Framework. This diagram visualizes the main pillars of semiconductor regulation and their direct operational impacts, based on industry analysis [17] [19].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

The following table details key reagents and materials essential for conducting SPR experiments, a technique central to interaction analysis in drug development and nanotechnology.

Table 5: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for SPR Analysis

| Item | Function / Application | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| CM5 Sensor Chip | A gold chip coated with a carboxymethyl-dextran matrix that provides a hydrophilic environment for ligand immobilization [14]. | The 3D matrix can cause steric hindrance for large analytes like nanoparticles; suitable for most proteins and small molecules [14]. |

| C1 Sensor Chip | A gold chip with a flat, 2D surface and minimal matrix [14]. | Preferred for large analytes like nanoparticles to ensure access to all immobilized ligands; may have higher non-specific binding [14]. |

| EDC/NHS Chemistry | A common cross-linking chemistry (using 1-Ethyl-3-(3-dimethylaminopropyl)carbodiimide and N-Hydroxysuccinimide) for covalent immobilization of ligands containing amine groups to the chip surface [14]. | Must be optimized to preserve the biochemical activity of the immobilized ligand [14]. |

| Regeneration Buffers | Solutions (e.g., low pH, high salt, or mild detergent) used to remove bound analyte from the immobilized ligand without damaging the chip surface [14]. | A proper regeneration protocol is critical for reusing the sensor chip for 50-100 runs with reproducible results [14]. |

| HBS-EP Buffer | A standard running buffer (HEPES Buffered Saline with EDTA and Polysorbate 20) for SPR experiments. | Provides a stable, physiologically-relevant baseline and contains surfactants to minimize non-specific binding. |

| Biotinylated Ligands | Ligands modified with biotin for capture on streptavidin-coated sensor chips [15]. | Provides a stable and oriented immobilization, often preserving ligand activity. Useful for capturing complex molecules like polymer-drug conjugates [15]. |

The trajectory of surface analysis is being powerfully shaped by the synergistic demands of the semiconductor and nanotechnology sectors, all within a framework of rigorous global regulations. As this guide has benchmarked, techniques like SPR, STM, and AFM provide the critical data needed to drive innovation, from characterizing atomic-scale structures to quantifying biomolecular interactions for next-generation therapeutics. The experimental protocols and toolkit detailed herein offer a foundation for researchers to generate reproducible, high-quality data. Success in this evolving landscape will depend on the ability to not only leverage these advanced analytical techniques but also to seamlessly integrate compliance and standardization into the research and development workflow, ensuring that scientific breakthroughs can efficiently and safely reach the market.

Surface analysis technologies, such as X-ray Photoelectron Spectroscopy (XPS) and Atomic Force Microscopy (AFM), have become indispensable tools in modern materials science, semiconductor development, and pharmaceutical research. These techniques provide critical insights into the atomic composition, chemical states, and topographic features of material surfaces, enabling breakthroughs in product development and quality control. The global adoption and advancement of these technologies, however, follow distinct regional patterns shaped by varying economic, industrial, and policy drivers. As of 2025, the global surface analysis market is estimated to be valued at USD 6.45 billion, with projections indicating growth to USD 9.19 billion by 2032 at a compound annual growth rate (CAGR) of 5.18% [6].

This comparative analysis examines the technological landscapes of North America and the Asia-Pacific region, two dominant forces in the surface analysis field. North America currently leads in market share through technological sophistication and established research infrastructure, while Asia-Pacific demonstrates remarkable growth momentum driven by rapid industrialization and strategic government initiatives. Understanding these regional paradigms provides researchers and industry professionals with valuable insights for strategic planning, collaboration, and technology investment decisions in an increasingly competitive global landscape.

Quantitative Regional Market Analysis

Current Market Size and Growth Projections

Table 1: Global Surface Analysis Market Metrics by Region (2025-2032)

| Region | 2025 Market Share | 2032 Projected Market Share | CAGR (2025-2032) | Market Size (2025) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| North America | 37.5% [6] | Data Not Available | ~5.18% (Global Average) [6] | Leading regional market [6] |

| Asia-Pacific | 23.5% [6] | Data Not Available | Highest regional growth rate [6] | Fastest-growing region [6] |

| Europe | Data Not Available | Data Not Available | Data Not Available | Steady growth [20] |

Table 2: Regional Market Characteristics and Growth Drivers

| Region | Key Growth Drivers | Leading Industrial Applications | Technology Adoption Trends |

|---|---|---|---|

| North America | Established R&D infrastructure, semiconductor industry dominance, government funding [6] | Semiconductors (29.7% market share), healthcare, aerospace [6] | AI integration, advanced microscopy techniques, multimodal imaging [6] [21] |

| Asia-Pacific | Government initiatives (e.g., "Made in China 2025"), expanding electronics manufacturing, research investments [6] | Electronics, automotive, materials science [6] [22] | Rapid adoption of automation, focus on cost-effective solutions, emerging AI applications [23] [22] |

| Europe | Stringent regulatory standards, sustainability initiatives, advanced manufacturing [20] | Automotive, pharmaceuticals, industrial manufacturing [20] | High-precision instrumentation, quality control applications [20] |

The data reveals a distinct bifurcation in the global surface analysis landscape. North America maintains dominance with more than one-third of the global market share, supported by mature technological infrastructure and significant R&D expenditures. Meanwhile, Asia-Pacific demonstrates remarkable growth potential, positioned as the fastest-growing region despite currently holding a smaller market share. This growth trajectory is primarily fueled by massive investments in semiconductor fabrication facilities and expanding electronics manufacturing capabilities across China, Japan, and South Korea [6].

Regional Technology Adoption and Application Focus

Table 3: Regional Preferences in Surface Analysis Techniques

| Analytical Technique | North America Adoption | Asia-Pacific Adoption | Key Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Scanning Tunneling Microscopy (STM) | High (29.6% of global market) [6] | Growing | Semiconductor defect analysis, nanomaterials research [6] |

| X-ray Photoelectron Spectroscopy (XPS) | Well-established [6] | Rapidly expanding [6] | Chemical state analysis, thin film characterization [21] |

| Atomic Force Microscopy (AFM) | Advanced applications with AI integration [6] | Increasing adoption for quality control [6] | Surface topography, mechanical properties measurement [6] |

| Spectroscopy Techniques | Dominant in research institutions [6] | Focus on industrial applications [22] | Materials characterization, failure analysis [6] |

North America's technological edge manifests in its leadership in advanced techniques such as Scanning Tunneling Microscopy (STM), which holds 29.6% of the global market share [6]. This region demonstrates particular strength in atomic-scale surface characterization, leveraging these capabilities for fundamental research and high-value innovation in semiconductors and advanced materials. The presence of key instrument manufacturers like Thermo Fisher Scientific and Agilent Technologies further strengthens this technological ecosystem [6].

Asia-Pacific's adoption patterns reflect its manufacturing-intensive economy, with emphasis on techniques that support quality control and high-volume production. While the region is rapidly acquiring advanced capabilities, its distinctive advantage lies in the rapid implementation of these technologies within industrial settings. Countries like China, Japan, and South Korea are leveraging surface analysis to advance their semiconductor, display, and battery manufacturing sectors [6] [22].

Industry-Specific Application Focus

The application of surface analysis technologies reveals contrasting regional economic priorities. In North America, the semiconductors segment captures 29.7% of the market share, driven by the relentless pursuit of miniaturization and performance enhancement in electronic devices [6]. The material science segment follows with 23.8% share, supporting innovation in advanced alloys, composites, and functional coatings [6].

Asia-Pacific demonstrates more diverse application across multiple growth industries, with particular strength in electronics, automotive, and emerging materials development. Government initiatives such as China's "Made in China 2025" and South Korea's investments in nanotechnology provide strategic direction to these applications [6]. The region's competitive advantage stems from integrating surface analysis throughout manufacturing processes rather than confining it to research laboratories.

Experimental Protocols for Surface Analysis Benchmarking

Cross-Regional Semiconductor Surface Characterization Protocol

Objective: To quantitatively compare surface contamination levels on silicon wafers using X-ray Photoelectron Spectroscopy (XPS) across different regional manufacturing conditions.

Materials and Equipment:

- Silicon wafers with thermal oxide layer (100nm)

- XPS instrument with monochromatic Al Kα X-ray source

- Charge neutralization system

- Ultra-high vacuum chamber (<1×10⁻⁹ torr)

- Reference samples from NIST-traceable standards

Procedure:

- Sample Preparation: Cut wafer into 1cm×1cm squares using diamond scribe. Handle samples with vacuum tweezers only.

- Instrument Calibration: Verify energy scale using Au 4f₇/₂ (84.0 eV) and Cu 2p₃/₂ (932.7 eV) peaks. Adjust pass energy to 20 eV for high-resolution scans.

- Data Acquisition:

- Survey scan (0-1100 eV) at pass energy 160 eV to identify elemental composition

- High-resolution scans for C 1s, O 1s, Si 2p, and any contaminants detected

- Use spot size of 200μm with photoelectron take-off angle of 45°

- Data Analysis:

- Calculate atomic concentrations using manufacturer-supplied sensitivity factors

- Deconvolve C 1s peak to identify hydrocarbon contamination (284.8 eV) versus adventitious carbon

- Compare oxide layer composition (Si⁴+ at 103.5 eV) to reference standards

This protocol enables direct comparison of semiconductor surface quality across different geographical production facilities, particularly relevant for multinational corporations managing supply chains in both North America and Asia-Pacific regions.

Thin Film Thickness Measurement Correlation Study

Objective: To evaluate consistency of thin film thickness measurements using ellipsometry and X-ray reflectivity (XRR) across multiple research facilities.

Materials and Equipment:

- Silicon wafers with deposited SiO₂ films of varying thickness (10-200nm)

- Spectroscopic ellipsometer (wavelength range: 250-1700nm)

- X-ray diffractometer with reflectivity attachment (Cu Kα radiation)

- Surface profilometer as reference measurement

Procedure:

- Sample Distribution: Distribute identical sample sets to participating laboratories in North America and Asia-Pacific.

- Ellipsometry Measurements:

- Measure at three locations on each sample with 2mm spot size

- Use Cauchy model for transparent films with surface roughness correction

- Record Ψ and Δ values from 40° to 70° incidence angles in 5° increments

- XRR Measurements:

- Align sample to maintain incident angle 0-5° with 0.001° resolution

- Collect data until intensity drops below 10 counts per second

- Fit critical angle and oscillation period to determine thickness and density

- Data Correlation:

- Compare intra-technique variability within and between regions

- Establish inter-technique correlation coefficients

- Identify systematic measurement biases by region

This multi-technique approach provides methodological validation essential for cross-regional research collaborations and technology transfer initiatives between North America and Asia-Pacific institutions.

Visualization of Regional Technology Adoption Pathways

The following diagram illustrates the contrasting technology adoption pathways between North America and Asia-Pacific regions in surface analysis:

This diagram highlights the complementary nature of regional approaches. North America typically follows a science-driven pathway beginning with fundamental research, while Asia-Pacific often pursues a manufacturing-driven pathway focused on implementation and scaling. The dashed red lines indicate important knowledge transfer mechanisms that benefit both regions, with technology innovations from North America being optimized for mass production in Asia-Pacific, and practical application feedback from Asia-Pacific informing next-generation research priorities in North America.

Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Surface Analysis

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents and Reference Materials for Cross-Regional Surface Analysis Studies

| Reagent/Reference Material | Function | Regional Availability Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| NIST-Traceable Standard Reference Materials (SRMs) | Instrument calibration and measurement validation | Critical for cross-regional data correlation; available globally but subject to trade restrictions [21] |

| Certified Thin Film Thickness Standards | Calibration of ellipsometry and XRR measurements | Silicon-based standards from NIST (US) and NMIJ (Japan) enable regional comparability [6] |

| Surface Contamination Reference Samples | Method validation for contamination analysis | Composition varies by regional environmental factors; requires localized customization [21] |

| Charge Neutralization Standards | XPS analysis of insulating samples | Particularly important for organic materials and advanced polymers [21] |

| Sputter Depth Profiling Reference Materials | Optimization of interface analysis protocols | Certified layered structures with known interface widths [6] |

The selection and standardization of research reagents present unique challenges for multinational surface analysis studies. Recent trade tensions and tariffs have impacted the availability and cost of electron spectroscopy equipment and nanoindentation instruments sourced from Germany and Japan, potentially affecting research progress and laboratory operational costs [21]. Researchers engaged in cross-regional comparisons must establish robust material tracking protocols and maintain adequate inventories of critical reference standards to mitigate supply chain disruptions.

The comparative analysis of surface analysis adoption in North America and Asia-Pacific reveals distinct but complementary regional strengths. North America maintains leadership in technology innovation and advanced applications, particularly in semiconductors and materials science research. The region's well-established ecosystem of research institutions, major instrument manufacturers, and government funding creates an environment conducive to breakthrough innovations. The integration of artificial intelligence and machine learning for data interpretation and automation represents the next frontier in North America's technological advancement [6].

Asia-Pacific demonstrates remarkable growth momentum driven by manufacturing scale, cost optimization, and strategic government initiatives. The region's focus on industrial applications, particularly in electronics, automotive, and energy sectors, positions it as the fastest-growing market for surface analysis technologies [6]. With policies such as China's "Made in China 2025" and substantial investments in nanotechnology research, Asia-Pacific is rapidly closing the technological gap while leveraging its manufacturing advantages [6].

For researchers and drug development professionals, these regional patterns suggest strategic opportunities for cross-regional collaboration, leveraging North America's innovation capabilities alongside Asia-Pacific's manufacturing scaling expertise. The evolving landscape also underscores the importance of standardized protocols and reference materials to ensure data comparability across geographical boundaries. As surface analysis technologies continue to advance, their critical role in materials characterization, quality control, and fundamental research will further intensify global competition while simultaneously creating new opportunities for international scientific cooperation.

In the rapidly advancing fields of material science and pharmaceutical development, the precise characterization of surfaces has emerged as a critical enabling technology. Surface analysis techniques provide indispensable insights into material properties, interfacial interactions, and functional behaviors that directly impact product performance, safety, and efficacy. As these fields increasingly demand nanoscale precision and quantitative molecular-level understanding, benchmarking studies that objectively compare analytical techniques have become essential for guiding methodological selection and technological innovation.

The global surface analysis market, projected to grow from USD 6.45 billion in 2025 to USD 9.19 billion by 2032 at a 5.18% CAGR, reflects the expanding significance of these characterization methods across industrial and research sectors [6]. This growth is particularly driven by the semiconductor, pharmaceutical, and advanced materials industries, where surface properties directly influence functionality, bioavailability, and performance. This guide provides a comprehensive comparison of major surface analysis techniques, supported by experimental benchmarking data and detailed protocols, to inform researchers and development professionals in selecting and implementing the most appropriate methodologies for their specific applications.

Comparative Performance Analysis of Surface Analysis Techniques

Technical Specifications and Application Fit

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of Major Surface Analysis Techniques

| Technique | Resolution Capability | Information Obtained | Key Applications | Sample Requirements |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Scanning Tunneling Microscopy (STM) | Atomic-scale (sub-nm) | Surface topography, electronic properties | Conductive materials, semiconductor research, nanotechnology | Electrically conductive surfaces |

| Atomic Force Microscopy (AFM) | Atomic to nanoscale | Surface topography, mechanical properties, adhesion forces | Polymers, biomaterials, thin films, composites | Most solid materials (conductive and non-conductive) |

| X-ray Photoelectron Spectroscopy (XPS) | 5-10 μm lateral; 1-10 nm depth | Elemental composition, chemical state, empirical formula | Failure analysis, contamination identification, coating quality | Solid surfaces under ultra-high vacuum |

| Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR) | N/A (bulk measurement) | Binding kinetics, affinity constants, concentration analysis | Drug-target interactions, biomolecular binding studies | One binding partner must be immobilized on sensor chip |

| Contact Angle (CA) Analysis | Macroscopic (mm scale) | Wettability, surface free energy, adhesion tension | Coating quality, surface treatment verification, cleanliness | Solid, flat surfaces ideal; methods for uneven surfaces available |

Quantitative Performance Benchmarking

Table 2: Market Adoption and Sector Performance Metrics

| Technique/Application | Market Share (2025) | Projected Growth | Dominant End-use Industries |

|---|---|---|---|

| Scanning Tunneling Microscopy (by Technique) | 29.6% [6] | Stable | Semiconductors, materials research, nanotechnology |

| Material Science (by Application) | 23.8% [6] | Increasing | Advanced materials, polymers, composites development |

| Semiconductors (by End-use) | 29.7% [6] | Rapid | Semiconductor manufacturing, electronics |

| North America (by Region) | 37.5% [6] | Moderate | Diverse industrial and research applications |

| Asia Pacific (by Region) | 23.5% [6] | Fastest growing | Electronics manufacturing, growing industrial R&D |

Experimental Benchmarking Data and Protocols

Atomic Force Microscopy Tip Performance Benchmarking

Atomic Force Microscopy represents one of the most versatile surface analysis techniques, with performance heavily dependent on tip selection and functionalization. A comprehensive 2021 benchmarking study directly compared four atomically defined AFM tips for chemical-selective imaging on a nanostructured copper-oxide surface [24].

Table 3: Performance Comparison of Atomically Defined AFM Tips

| Tip Type | Rigidity | Chemical Reactivity | Spatial Resolution | Artifact Potential | Optimal Application |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Metallic Cu-tip | High | Highly reactive | Limited to attractive regime | High (tip changes) | Limited to non-reactive surfaces |

| Xe-tip | Very Low | Chemically inert | High in repulsive regime | Moderate (flexibility artifacts) | High-resolution imaging of well-defined surfaces |

| CO-tip | Low | Chemically inert | High in repulsive regime | Moderate (flexibility artifacts) | Molecular resolution on organic systems |

| CuOx-tip | High | Selectively reactive | High in repulsive regime | Low (reduced bending) | Chemical-selective imaging on inorganic surfaces |

Experimental Protocol: AFM Tip Benchmarking

- Surface Preparation: A partially oxidized Cu(110) surface exhibiting alternating stripes of bare Cu(110) and (2×1)O-reconstructed oxide stripes was prepared under ultra-high vacuum conditions [24].

- Tip Functionalization:

- Metallic Cu-tips: Electrochemically etched tungsten tips

- Xe-tips: Metallic tips functionalized by picking up a single Xe atom from the surface

- CO-tips: Metallic tips functionalized with a single CO molecule

- CuOx-tips: Copper tips with oxygen atom covalently bound in tetrahedral configuration

- Imaging Parameters: Experiments performed at ~5 K with qPlus sensors (resonance frequencies: 24-28 kHz), amplitudes of 0.8-1.0 Å, constant-height mode [24].

- Data Collection: Height-dependent imaging with Δf(Z)-spectroscopy at characteristic surface sites.

- Analysis: Comparison of contrast evolution, chemical identification capability, and artifact generation.

The study demonstrated that CuOx-tips provided optimal performance for inorganic surfaces, combining high rigidity with selective chemical reactivity that enabled clear discrimination between copper and oxygen atoms within the added rows without the bending artifacts characteristic of more flexible Xe- and CO-tips [24].

Surface Plasmon Resonance for Pharmaceutical Applications

Surface Plasmon Resonance has emerged as a powerful tool for quantifying biomolecular interactions in pharmaceutical development, particularly for targeted nanotherapeutics. SPR enables real-time, label-free analysis of binding events with high sensitivity (~pg/mm²) [14].

Experimental Protocol: SPR Analysis of Nanotherapeutics

- Chip Selection: CM5 (carboxymethyl-dextran) chips for most applications; C1 chips (no dextran) for larger nanoparticles to improve accessibility [14].

- Ligand Immobilization: Covalent immobilization via EDC/NHS chemistry targeting amine, thiol, or aldehyde groups. Optimal ligand density depends on analyte size and should reflect physiological relevance [14].

- Analyte Preparation: NanoRx formulations in appropriate running buffer with series of concentrations for kinetic analysis.

- Binding Experiment:

- Flow rate: 30 μL/min (higher rates reduce mass transfer limitations)

- Contact time: 60-300 seconds depending on binding kinetics

- Dissociation time: 60-600 seconds to monitor complex stability

- Regeneration: Surface regeneration between runs using appropriate conditions (e.g., mild acid/base, high salt) that remove bound analyte without damaging immobilized ligand.

- Data Analysis: Simultaneous fitting of association and dissociation phases from multiple analyte concentrations to determine kinetic parameters (kₐ, k𝒅) and equilibrium constants (K𝙳) [14].

SPR has been successfully applied to evaluate both specific and non-specific interactions of targeted nanotherapeutics, enabling optimization of targeting ligand density and assessment of off-target binding potential [14]. The technique can distinguish between formulations with low and high densities of targeting antibodies, providing critical data for pharmaceutical development.

Contact Angle Measurements on Complex Surfaces

Contact angle measurements provide vital information about surface wettability, a critical property for pharmaceutical development (e.g., coating uniformity, adhesion) and material science (e.g., hydrophobicity, self-cleaning surfaces). Standard sessile drop measurements assume ideal surfaces, but real-world applications often involve uneven or rough surfaces requiring specialized approaches [25] [26].

Experimental Protocol: Contact Angle on Uneven Surfaces

- Substrate Preparation: Identify relatively flat regions for droplet deposition. If unavailable, reduce droplet volume to fit available flat areas [26].

- Measurement Setup:

- Use optical tensiometer/goniometer with adjustable stage

- Deposit 2-5 μL liquid droplets (typically water for hydrophilicity/hydrophobicity assessment)

- Capture high-resolution images immediately after deposition

- Baseline Positioning:

- Set baselines for left and right contact points independently when surface unevenness prevents uniform baseline

- Adjust baseline height to account for meniscus effects from droplet movement or evaporation

- Region of Interest Optimization:

- For high contact angles (>60°), lower top ROI line to halfway up droplet to improve polynomial fit

- Adjust side boundaries to capture complete droplet edge without extraneous features

- Data Analysis:

- Use appropriate fitting algorithm (typically circle or ellipse fitting for static contact angle)

- Report advancing and receding angles separately for uneven surfaces

- Calculate contact angle hysteresis (difference between advancing and receding angles) as indicator of surface heterogeneity [25]

For surfaces with significant unevenness, dynamic contact angle measurements (advancing and receding) using the Wilhelmy plate method may provide more reliable characterization, though this requires uniform, homogeneous samples with known perimeter [25].

Application-Specific Workflows and Decision Pathways

Material Science Development Pathway

Material Science Surface Analysis Workflow

Pharmaceutical Development Pathway

Pharmaceutical Development Surface Analysis Workflow

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Table 4: Key Research Reagents and Materials for Surface Analysis

| Category | Specific Products/Techniques | Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| SPR Chips | CM5 (carboxymethyl-dextran), C1 (flat) | Ligand immobilization for binding studies | CM5 for most applications; C1 for nanoparticles to improve accessibility [14] |

| AFM Probes | CuOx-tips, CO-tips, Xe-tips | Surface imaging with chemical specificity | CuOx-tips optimal for inorganic surfaces; CO/Xe-tips for organic systems [24] |

| Contact Angle Liquids | Water, diiodomethane, ethylene glycol | Surface energy calculations | Multiple liquids required for surface free energy component analysis |

| Calibration Standards | NIST reference wafers, grating samples | Instrument calibration and verification | Essential for cross-laboratory comparability and quality assurance [6] |

| Software Tools | DockAFM, SPIP, Analysis Software | Data processing and interpretation | DockAFM enables correlation of AFM data with 3D structural models [27] |

The benchmarking data presented demonstrates that optimal surface analysis methodology selection depends heavily on specific application requirements. STM provides unparalleled atomic-scale resolution but only for conductive materials. AFM offers broader material compatibility with multiple contrast mechanisms, with tip selection critically impacting data quality. SPR delivers exceptional sensitivity for binding interactions relevant to pharmaceutical development. Contact angle measurements remain indispensable for surface energy assessment but require careful methodology adaptation for non-ideal surfaces.

The integration of artificial intelligence and machine learning for data interpretation represents an emerging trend that enhances precision and efficiency across all major surface analysis techniques [6]. Additionally, the growing emphasis on sustainability initiatives is prompting more thorough surface evaluations to develop eco-friendly materials and processes [6]. As material science and pharmaceutical development continue to advance toward nanoscale engineering and personalized medicine, the strategic implementation of appropriately benchmarked surface analysis methods will remain fundamental to innovation and quality assurance.

Method Selection and Practical Applications: Optimizing Surface Analysis for Drug Delivery and Nanomaterials

Nanoparticle Characterization for Enhanced Bioavailability

In pharmaceutical development, nanoparticles (NPs) are transforming drug delivery systems by enhancing drug solubility, enabling targeted delivery, and controlling the release of therapeutic agents, thereby significantly improving bioavailability and reducing side effects [28]. The performance of these nanocarriers—including their stability, cellular uptake, biodistribution, and targeting efficiency—is governed by their physicochemical properties [29]. Consequently, rigorous characterization is not merely a supplementary analysis but a fundamental prerequisite for designing effective, reliable, and clinically viable nanoformulations. This guide provides a comparative analysis of key analytical techniques, offering experimental protocols and benchmarking data to inform method selection for research focused on enhancing drug bioavailability.

Comparative Analysis of Key Characterization Techniques

A diverse toolbox of analytical techniques is available for nanoparticle characterization, each with distinct strengths, limitations, and optimal application ranges. The choice of technique depends on the parameter of interest, the complexity of the sample matrix, and the required information level (e.g., ensemble average vs. single-particle data) [30] [31].

Table 1: Comparison of Primary Nanoparticle Characterization Techniques

| Technique | Measured Parameters | Principle | Key Advantages | Inherent Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cryogenic Transmission Electron Microscopy (Cryo-TEM) | Size, morphology, internal structure, lamellarity, aggregation state [30] | High-resolution imaging of flash-frozen, vitrified samples in native state [30] | "Golden standard"; direct visualization; detailed structural data; minimal sample prep [30] | Specialized equipment/expertise; potential for image background noise [30] |

| Dynamic Light Scattering (DLS) | Hydrodynamic diameter, size distribution (intensity-weighted), aggregation state [30] | Fluctuations in scattered light from Brownian motion [30] | Fast, easy, non-destructive; measures sample in solution [30] | Assumes spherical particles; low resolution; biased by large aggregates/impurities [30] |

| Single-Particle ICP-MS (spICP-MS) | Particle size distribution (number-based), particle concentration, elemental composition [31] | Ion plumes from individual NPs in ICP-MS detected as signal pulses [31] | High sensitivity; elemental composition; number-based distribution at low concentrations [31] | Requires specific elemental composition; complex data analysis [31] |

| Particle Tracking Analysis (PTA/NTA) | Hydrodynamic size, particle concentration (relative) [31] | Tracking Brownian motion of single particles via light scattering [31] | Direct concentration estimation; handles polydisperse samples [31] | Lower size resolution vs. TEM; performance depends on optical properties [31] |

| Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (NMR) Spectroscopy | Ligand structure, conformation, binding mode, density, dynamics [32] | Analysis of nuclear chemical environment [32] | Comprehensive molecular structure data; studies ligand-surface interactions [32] | Requires large sample amounts; signal broadening for bound ligands [32] |

Quantitative Benchmarking of Technique Performance

Interlaboratory comparisons (ILCs) provide critical data on the real-world performance and reliability of characterization methods. These studies benchmark techniques against standardized materials and complex formulations to assess their accuracy and precision.

Table 2: Benchmarking Data from Interlaboratory Comparisons (ILCs)

| Technique | Sample Analyzed | Reported Consensus Value (Size) | Interlaboratory Variability (Robust Standard Deviation) | Key Performance Insight |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Particle Tracking Analysis (PTA) | 60 nm Au NPs (aqueous suspension) [31] | 62 nm [31] | 2.3 nm [31] | Excellent agreement for pristine NPs in simple matrices [31] |

| Single-Particle ICP-MS (spICP-MS) | 60 nm Au NPs (aqueous suspension) [31] | 61 nm [31] | 4.9 nm [31] | Good performance for size; particle concentration determination is more challenging [31] |

| spICP-MS & TEM/SEM | Sunscreen Lotion (TiO₂ particles) [31] | Nanoscale (compliant with EU definition) [31] | Larger variations in complex matrices [31] | Orthogonal techniques agree on regulatory classification [31] |

| spICP-MS, PTA & TEM/SEM | Toothpaste (TiO₂ particles) [31] | Not fitting EU NM definition [31] | Techniques agreed on classification [31] | Reliable analysis possible in complex consumer product matrices [31] |

Essential Research Reagents and Materials

A successful characterization workflow relies on specific, high-quality reagents and materials. The following table details essential items for key experiments.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Nanoparticle Characterization

| Reagent/Material | Function/Application | Experimental Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Citrate-stabilized Gold Nanoparticles (e.g., 60 nm) | Standard reference material for method calibration and interlaboratory comparisons [31] | Ensures data comparability; available from commercial suppliers like NanoComposix [31] |

| Single-stranded DNA-functionalized Au NPs | Model system for studying controlled, biomolecule-driven aggregation in colorimetric sensing [33] | Enables tunable aggregation; used to test sensor performance and optimize parameters [33] |

| MTAB ( (11-mercaptohexadecyl)trimethylammonium bromide) | Model surfactant ligand for studying packing density, structure, and dynamics on nanoparticle surfaces [32] | Used with NMR to analyze ligand conformation and mobility on Au surfaces [32] |

| Liquid Nitrogen | Essential for sample preparation and storage in cryo-TEM [30] | Used for flash-freezing samples to create vitrified ice for native-state imaging [30] |

| ImageJ / FIJI Software | Open-source image processing for analysis of TEM images (contrast adjustment, filtering, scale bars) [34] | Enables batch processing; critical for preparing publication-quality images [34] |

Experimental Protocols for Key Characterization Workflows

Protocol: spICP-MS for Size and Concentration of Metal-Containing NPs

This protocol is adapted from ILCs for characterizing metallic nanoparticles like Au and Ag [31].

- Sample Preparation: Dilute the nanoparticle suspension to a concentration of 0.01 to 1 µg/L (total element mass) using a compatible aqueous solvent (e.g., ultrapure water). This low concentration is critical to ensure that each detected signal pulse originates from a single nanoparticle [31].

- Instrument Setup: Use an ICP-MS instrument with a fast time resolution (typically 100 µs to 10 ms per reading). Introduce the sample, ensuring a stable plasma and consistent sample introduction rate [31].

- Data Acquisition: Acquire data in time-resolved analysis (TRA) or single-particle mode. Collect data for a sufficient duration to accumulate at least 10,000 particle events for a statistically robust size distribution [31].

- Data Processing and Analysis:

- Signal Thresholding: Set a threshold signal intensity to differentiate particle events from the dissolved ion background.

- Size Calibration: Convert the intensity of each particle pulse to mass using a dissolved ionic standard of the same element. Calculate the particle diameter from the mass, assuming a spherical shape and known density [31].

- Concentration Calculation: The particle number concentration is calculated from the number of detected particles per unit time and the sample flow rate [31].

Protocol: NMR for Surface Ligand Characterization

This protocol outlines the use of solution-phase NMR to analyze organic ligands on nanoparticle surfaces [32].

- Sample Preparation: Concentrate the nanoparticle solution to the maximum possible level without causing aggregation. For larger nanoparticles (>20 nm), a significant amount of sample may be required due to the low weight percentage of surface ligands [32]. Use a deuterated solvent for locking and shimming.

- Data Acquisition:

- Run a standard ( ^1H ) NMR spectrum.

- Compare the spectrum of ligand-functionalized NPs with that of the free ligand. Successfully attached ligands will show broadened and/or shifted resonance peaks [32].

- Employ advanced 2D-NMR techniques for deeper insight:

- DOSY (Diffusion Ordered Spectroscopy): Differentiates between bound ligands (slow diffusion) and free, unbound ligands (fast diffusion) in the sample [32].

- NOESY/ROESY (Nuclear Overhauser Effect Spectroscopy): Provides through-space correlations, revealing information about the spatial proximity and packing of neighboring ligands on the nanoparticle surface [32].

- Data Analysis: Analyze chemical shifts, peak broadening, and diffusion coefficients to confirm ligand attachment, assess binding modes, and investigate ligand dynamics and packing density [32].

Protocol: Cryo-TEM for Structural Analysis

Cryo-TEM is considered the gold standard for directly visualizing the size, shape, and internal structure of nanoparticles in a native, hydrated state [30].

- Sample Vitrification: Apply a small volume (e.g., 3-5 µL) of the nanoparticle suspension to a holey carbon TEM grid. Blot away excess liquid to form a thin liquid film across the holes. Rapidly plunge the grid into a cryogen (typically liquid ethane) cooled by liquid nitrogen. This process vitrifies the water, preventing ice crystal formation and preserving the native structure of the particles [30].

- Imaging: Transfer the vitrified grid under liquid nitrogen into the cryo-TEM microscope. Acquire images at various magnifications under low-dose conditions to minimize beam damage [30].

- Image Processing (Contrast Enhancement and Scale Bar Addition):

- Software: Use ImageJ or FIJI (open source) [34].

- Contrast Adjustment: Open the image. Select

Image > Adjust > Brightness/Contrast. Adjust the minimum and maximum sliders to bring the features of interest (the nanoparticles) into clear view. The "Auto" function can provide a good starting point [34]. - Filtering (Optional): To reduce noise, apply a mean filter via

Process > Filters > Mean. A radius between 0.5 and 3 is typically effective [34]. - Adding a Scale Bar: Find the pixel size for the image magnification (usually in the microscope metadata or report). Go to

Analyze > Set Scale. Set "Distance in pixels" to 1, "Known distance" to the pixel size, and "Unit of length" to nm. Click "OK". Then, add the scale bar viaAnalyze > Tools > Scale Bar. Adjust the width, location, and appearance in the dialog box [34].

Characterizing nanoparticles is a multi-faceted challenge that requires an integrated, orthogonal approach. No single technique can provide a complete picture; confidence in results is built by correlating data from multiple methods [31]. For instance, while DLS offers a quick assessment of hydrodynamic size in solution, cryo-TEM provides definitive visual proof of morphology and state of aggregation [30]. Similarly, spICP-MS delivers ultrasensitive, number-based size distributions for metallic elements, and NMR gives unparalleled insight into the molecular nature of the surface coat [31] [32]. The future of nanoparticle characterization for enhanced bioavailability lies in the continued development of standardized protocols, the benchmarking of methods for complex biological matrices, and the integration of advanced data analysis and modeling. This rigorous, multi-technique framework is essential for translating promising nanocarriers from the laboratory into safe and effective clinical therapies.