Bridging the Materials Gap in Model Systems: Advanced Strategies for Predictive Biomedical Research

This article addresses the critical challenge of the 'materials gap'—the disconnect between simplified model systems used in research and the complex reality of clinical applications.

Bridging the Materials Gap in Model Systems: Advanced Strategies for Predictive Biomedical Research

Abstract

This article addresses the critical challenge of the 'materials gap'—the disconnect between simplified model systems used in research and the complex reality of clinical applications. Aimed at researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, it provides a comprehensive framework for understanding, troubleshooting, and overcoming this gap. We explore the foundational causes and impacts, present cutting-edge methodological solutions including AI and digital twins, offer strategies for optimizing R&D workflows, and establish robust validation and comparative analysis protocols to enhance the predictive power and clinical translatability of preclinical research.

Understanding the Materials Gap: Defining the Disconnect Between Research Models and Clinical Reality

Defining the 'Materials Gap' in Biomedical and Drug Development Contexts

FAQ 1: What is the "Materials Gap" in model systems research?

The "Materials Gap" describes the significant difference between the simplified, idealized materials used in research and the complex, often heterogeneous, functional materials used in real-world applications [1] [2]. In catalysis and biomedical research, this means that studies often use pure, single-crystal surfaces or highly controlled model polymers under perfect laboratory conditions. In contrast, real-world industrial catalysts are irregularly shaped nanoparticles on high-surface-area supports, and real biomedical implants function in the dynamic, complex environment of the human body [3] [1]. This gap poses a major challenge in translating promising laboratory results into effective commercial products and therapies.

FAQ 2: How does the Materials Gap manifest in drug development?

In drug development, a closely related concept is the "Translational Gap" or "Valley of Death," which is the routine failure to successfully move scientific discoveries from the laboratory bench to clinical application at the patient bedside [4]. A key reason for this failure is that initial laboratory models (the "materials" of the research) do not adequately predict how a therapy will perform in the complex human system. Pre-clinical failure rates for novel therapies are around 90%, with an average time-to-market of 10-15 years and costs upwards of $2.5 billion [4]. This gap highlights a translatability problem where the model systems used in early research are not accurate enough proxies for human physiology.

FAQ 3: What are the consequences of the Materials Gap for my research?

Ignoring the Materials Gap can lead to several critical issues in your R&D pipeline:

- Poor Predictive Power: Data generated from overly simplistic models may not accurately forecast the performance, efficacy, or safety of a material or drug in a real-world setting [2]. A model that works perfectly on a single-crystal surface may fail on a practical, high-surface-area catalyst [1].

- High Attrition Rates: As noted above, this lack of predictive power is a primary driver of the high failure rates in drug development, leading to wasted resources and time [4].

- Slowed Innovation: The inability to reliably bridge this gap makes it difficult to design new materials and therapies in a rational, efficient manner, slowing down the entire innovation cycle.

FAQ 4: What are some established methodologies to bridge the Materials Gap?

Researchers are employing several advanced methodologies to make model systems more representative of real-world conditions.

Table: Experimental Protocols for Bridging the Materials Gap

| Methodology | Description | Key Application |

|---|---|---|

| In Situ/Operando Studies | Analyzing materials under actual operating conditions (e.g., high pressure, in biological fluid) rather than in a vacuum or idealized buffer [2]. | Directly observing catalyst behavior during reaction or biomaterial integration in real-time [3] [2]. |

| Advanced Computational Modeling | Using density functional theory (DFT) and other simulations on more realistic, fully relaxed nanoparticle models rather than infinite, perfect crystal slabs [1]. | Predicting the stability and activity of nanocatalysts and biomaterials at the nanoscale [1]. |

| Advanced Material Fabrication | Using techniques like additive manufacturing (3D printing) and laser reductive sintering to create conductive structures with desired shapes and properties [3]. | Creating implantable biosensors with complex geometries and enhanced biocompatibility [3]. |

| Surface Engineering | Modifying the surface of materials with functional groups (e.g., -CH3, -NH2, -COOH) or doping with nanomaterials (e.g., graphene) to tailor their interaction with the biological environment [3]. | Improving the hemocompatibility and electrical conductivity of materials for implantable devices [3]. |

Troubleshooting Guide: Common Experimental Pitfalls

Problem: My model catalyst shows high activity in the lab, but performance drops significantly in the pilot reactor.

- Potential Cause 1: The Pressure Gap. You characterized and tested your model system under ultra-high vacuum (UHV) conditions, but the industrial process runs at much higher pressures where adsorbate-adsorbate interactions become critical [2].

- Solution: Transition to in situ characterization techniques that can operate at or near real-world pressure and temperature conditions to observe the catalyst's active state [2].

- Potential Cause 2: The Materials Gap. You used a pristine single-crystal surface for your studies, but the real catalyst consists of irregularly shaped nanoparticles supported on a high-surface-area material, presenting different active sites and behaviors [1] [2].

- Solution: Incorporate nanoparticle models in computational studies [1] and synthesize catalyst samples that more closely mimic the structural and chemical heterogeneity of the industrial catalyst.

Problem: My biomaterial performs excellently in vitro, but fails in an animal model due to unexpected host responses or lack of functionality.

- Potential Cause: Overly Simplified In Vitro Environment. The controlled, static conditions of a cell culture plate do not replicate the mechanical stresses, dynamic fluid flow, complex immune cell populations, and biochemical signaling of a living organism [3].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

Table: Essential Materials for Advanced Model Systems

| Reagent/Material | Function | Field of Use |

|---|---|---|

| Decellularized ECM (dECM) | A biological scaffold that retains the natural 3D structure and composition of a tissue's extracellular matrix, providing a realistic microenvironment for cells [3]. | Tissue Engineering, Regenerative Medicine |

| Conductive Polymers (e.g., Polyaniline) | Polymers that can conduct electricity, often doped with nanomaterials like graphene to enhance conductivity and biocompatibility [3]. | Implantable Biosensors, Flexible Electronics |

| Nanoporous Gold Alloys (e.g., AgAu) | Model catalyst systems with high surface area and tunable composition that can help bridge the materials gap between single crystals and powder catalysts [2]. | Heterogeneous Catalysis, Sensor Technology |

| Polyethylene Glycol (PEG) | A synthetic, biocompatible polymer used to functionalize surfaces and create hydrogels; it is amphiphilic, non-toxic, and exhibits low immunogenicity [3]. | Drug Delivery, Bioconjugation, Hydrogel Fabrication |

| Info-Gap Uncertainty Models | A mathematical framework (not a physical reagent) used to model and manage severe uncertainty in system parameters, such as material performance under unknown conditions [5]. | Decision Theory, Risk Analysis for Material/Process Design |

Experimental Workflow for Bridging the Materials Gap

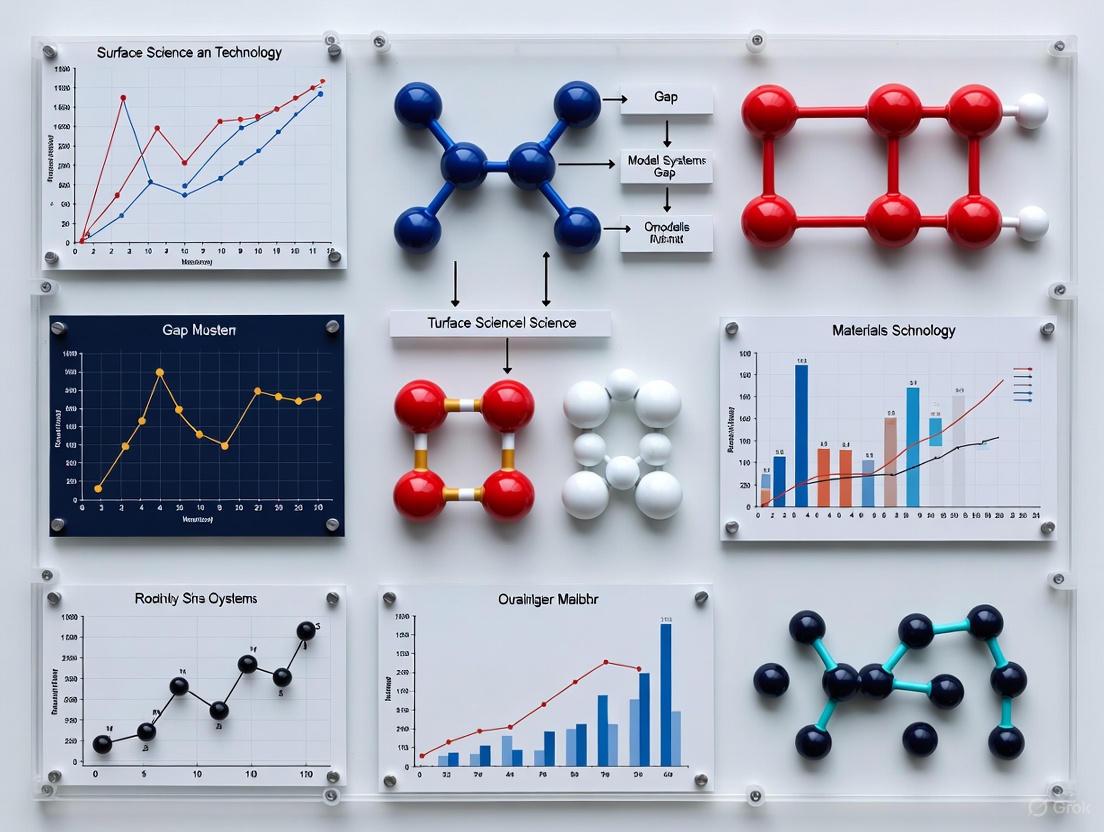

The following diagram illustrates a robust, iterative workflow for designing experiments that proactively address the Materials Gap.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

FAQ 1: What is the core "materials gap" challenge in model systems research? A significant challenge is that many AI and computational models for materials and molecular discovery are trained on simplified 2D representations, such as SMILES strings, which omit critical 3D structural information. This limitation can cause models to miss intricate structure-property relationships vital for accurate prediction in complex biological environments [6].

FAQ 2: How can I troubleshoot an experiment with unexpected results, like a failed molecular assay? A systematic approach is recommended [7] [8]:

- Identify the Problem: Clearly define the issue without assuming the cause (e.g., "no PCR product" instead of "the polymerase is bad") [7].

- List Possible Explanations: Consider all variables, including reagents, equipment, and procedural steps [7].

- Check Controls and Data: Verify that appropriate positive and negative controls were used and yielded expected results. Check reagent storage conditions and expiration dates [7] [8].

- Eliminate and Test: Rule out the simplest explanations first. Then, test remaining variables one at a time through experimentation, such as checking DNA template quality or antibody concentrations [7] [8].

- Document Everything: Meticulously record all steps, changes, and outcomes in a lab notebook [8].

FAQ 3: My AI model for molecular property prediction performs poorly on real-world data. What could be wrong? This is often a data quality and representation issue. Models trained on limited datasets (e.g., only small molecules or specific element types) lack the chemical diversity needed for generalizability. Leveraging larger, more diverse datasets like Open Molecules 2025 (OMol25), which includes 3D molecular snapshots with DFT-level accuracy across a wide range of elements, can significantly improve model robustness and real-world applicability [9].

FAQ 4: What is a more effective experimental strategy than testing one factor at a time? Design of Experiments (DOE) is a powerful statistical method that allows researchers to simultaneously investigate the impact of multiple factors and their interactions. While the one-factor-at-a-time (OFAT) approach can miss critical interactions, DOE provides a more complete understanding of complex biological systems with greater efficiency and fewer resources [10].

Troubleshooting Guides

Guide 1: Troubleshooting Failed Protein Detection (e.g., Immunohistochemistry)

Problem: A dim or absent fluorescence signal when detecting a protein in a tissue sample [8].

Step-by-Step Troubleshooting:

- Repeat the Experiment: Before extensive troubleshooting, simply repeat the protocol to rule out simple human error [8].

- Verify the Scientific Basis: Revisit the literature. Is the target protein truly expected to be present at detectable levels in your specific tissue type? A dim signal might be biologically accurate [8].

- Inspect Controls:

- If a positive control (e.g., a tissue known to express the protein highly) also shows a dim signal, the protocol is likely at fault.

- If the positive control works, the issue may be with your specific sample or target [8].

- Check Equipment and Reagents:

- Reagents: Confirm all antibodies and solutions have been stored correctly and are not expired. Visually inspect solutions for cloudiness or precipitation [7] [8].

- Antibody Compatibility: Ensure the secondary antibody is specific to the host species of your primary antibody.

- Equipment: Verify the microscope and fluorescence settings are configured correctly [8].

- Change Variables Systematically: Alter one variable at a time and assess the outcome. Logical variables to test, in a suggested order, include [8]:

- Microscope light settings or exposure time (easiest to check).

- Concentration of the secondary antibody.

- Concentration of the primary antibody.

- Fixation time or number of wash steps.

Guide 2: Troubleshooting a Failed PCR

Problem: No PCR product is detected on an agarose gel [7].

Systematic Investigation:

- Positive Control: Did a known working DNA template produce a band? If not, the issue is with the PCR system itself, not the specific sample [7].

- Reagents: Check the expiration and storage conditions of your PCR kit components (Taq polymerase, MgCl₂, buffer, dNTPs) [7].

- Template DNA: Assess the quality and concentration of your DNA template via gel electrophoresis and a spectrophotometer [7].

- Primers: Verify primer design, specificity, and concentration.

- Thermal Cycler: Confirm the PCR machine's block temperature is calibrated correctly.

Data Presentation

Table 1: Key Limitations of Current Molecular Datasets and Promising Solutions

| Challenge | Impact on Research | Emerging Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Dominance of 2D Representations (e.g., SMILES) [6] | Omits critical 3D structural information, leading to inaccurate property predictions for complex biological environments. | Adoption of 3D structural datasets like OMol25 [9]. |

| Lack of Chemical Diversity [6] | Models fail to generalize to molecules with elements or structures not well-represented in training data (e.g., heavy metals, biomolecules). | OMol25 includes over 100 million snapshots with up to 350 atoms, spanning most of the periodic table [9]. |

| Data Scarcity for Large Systems | High-fidelity simulation of scientifically relevant, large molecular systems (e.g., polymers) is computationally prohibitive. | Machine Learned Interatomic Potentials (MLIPs) trained on DFT data can predict with the same accuracy but 10,000x faster [9]. |

Table 2: Research Reagent Solutions for Advanced Materials Discovery

| Reagent / Tool | Function | Application in Bridging the Materials Gap |

|---|---|---|

| OMol25 Dataset [9] | A massive, open dataset of 3D molecular structures and properties calculated with Density Functional Theory (DFT). | Provides the foundational data for training AI models to predict material behavior in complex, real-world scenarios, moving beyond simplified models. |

| Machine Learned Interatomic Potentials (MLIPs) [9] | AI models trained on DFT data that simulate atomic interactions with near-DFT accuracy but much faster. | Enables rapid simulation of large, biologically relevant atomic systems (e.g., protein-ligand binding) that were previously impossible to model. |

| Vision Transformers [6] | Advanced computer vision models. | Used to extract molecular structure information from images in scientific documents and patents, enriching datasets. |

| Design of Experiments (DOE) Software [10] | Statistical tools for designing experiments that test multiple factors simultaneously. | Uncovers critical interactions between experimental factors in complex biological systems, leading to more robust and predictive models. |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol: Extracting and Associating Materials Data from Scientific Literature

This methodology is critical for building the comprehensive datasets needed to close the materials gap [6].

1. Data Collection and Parsing:

- Objective: Gather multimodal data from text, tables, and images in scientific papers, patents, and reports.

- Method: Use automated tools to parse documents. For text, apply Named Entity Recognition (NER) models to identify material names and properties [6]. For images, employ Vision Transformers or specialized algorithms like Plot2Spectra to extract data from spectroscopy plots or DePlot to convert charts into structured tables [6].

2. Multimodal Data Integration:

- Objective: Associate extracted materials data with their described properties from different parts of a document.

- Method: Leverage schema-based extraction with advanced Large Language Models (LLMs) to accurately link entities mentioned in text with data from figures and tables [6]. Models act as orchestrators, using specialized tools for domain-specific tasks.

3. Data Validation and Curation:

- Objective: Ensure the quality and reliability of the extracted dataset.

- Method: Implement consistency checks and validate extracted data against known chemical rules or databases. This step is crucial to avoid propagating errors from noisy or inconsistent source information [6].

The drug discovery pipeline is marked by a pervasive challenge: the failure of promising preclinical research to successfully translate into clinical efficacy and safety. This translational gap represents a significant materials gap in model systems research, where traditional preclinical models often fail to accurately predict human biological responses. With over 90% of investigational drugs failing during clinical development [11] and the success rate for Phase 1 drugs plummeting to just 6.7% in 2024 [12], the industry faces substantial productivity and attrition challenges. This technical support center provides troubleshooting guidance and frameworks to help researchers navigate these complex translational obstacles through improved experimental designs, validation strategies, and advanced methodological approaches.

Understanding the Translational Gap

The Scale of the Problem

Drug development currently operates at unprecedented levels of activity with 23,000 drug candidates in development, yet faces the largest patent cliff in history alongside rising development costs and timelines [12]. The internal rate of return for R&D investment has fallen to 4.1% - well below the cost of capital [12]. This productivity crisis stems fundamentally from failures in translating preclinical findings to clinical success.

Table 1: Clinical Trial Success Rates (ClinSR) by Therapeutic Area [13]

| Therapeutic Area | Clinical Trial Success Rate | Key Challenges |

|---|---|---|

| Oncology | Variable by cancer type | Tumor heterogeneity, resistance mechanisms |

| Infectious Diseases | Lower than average | Anti-COVID-19 drugs show extremely low success |

| Central Nervous System | Below average | Complexity of blood-brain barrier, disease models |

| Metabolic Diseases | Moderate | Species-specific metabolic pathways |

| Cardiovascular | Higher than average | Better established preclinical models |

Root Causes of Failed Translation

The troubling chasm between preclinical promise and clinical utility stems from several fundamental issues in model systems research:

Poor Human Correlation of Traditional Models: Over-reliance on animal models with limited human biological relevance [14]. Genetic, immune system, metabolic, and physiological variations between species significantly affect biomarker expression and drug behavior [14].

Disease Heterogeneity vs. Preclinical Uniformity: Human populations exhibit significant genetic diversity, varying treatment histories, comorbidities, and progressive disease stages that cannot be fully replicated in controlled preclinical settings [14].

Inadequate Biomarker Validation Frameworks: Unlike well-established drug development phases, biomarker validation lacks standardized methodology, with most identified biomarkers failing to enter clinical practice [14].

Troubleshooting Guides: Common Experimental Challenges

Problem: Lack of Assay Window in TR-FRET Assays

Symptoms: No detectable signal difference between experimental conditions; inability to distinguish positive from negative controls.

Root Causes:

- Incorrect instrument setup, particularly emission filter configuration [15]

- Improper reagent preparation or storage conditions

- Incorrect plate reader settings or calibration

Solutions:

- Verify Instrument Configuration: Confirm that emission filters exactly match manufacturer recommendations for your specific instrument model [15].

- Perform Control Validation: Test microplate reader TR-FRET setup using existing reagents before beginning experimental work [15].

- Validate Reagent Quality: Check Certificate of Analysis for proper storage conditions and expiration dates.

Preventative Measures:

- Establish standardized instrument validation protocols before each experiment

- Implement reagent quality control tracking systems

- Create standardized operating procedures for assay setup

Problem: Inconsistent EC50/IC50 Values Between Labs

Symptoms: Significant variability in potency measurements for the same compound across different research groups; inability to reproduce published results.

Root Causes:

- Differences in stock solution preparation, typically at 1 mM concentrations [15]

- Variations in cell passage number or culture conditions

- Protocol deviations in compound handling or dilution schemes

Solutions:

- Standardize Stock Solutions: Implement validated compound weighing and dissolution protocols across collaborating laboratories.

- Cross-Validate Assay Conditions: Conduct parallel experiments using shared reference compounds to identify systematic variability sources.

- Document Deviations: Maintain detailed records of all protocol modifications and potential confounding factors.

Problem: Failed Biomarker Translation

Symptoms: Biomarkers that show strong predictive value in preclinical models fail to correlate with clinical outcomes; inability to stratify patient populations effectively.

Root Causes:

- Over-reliance on single time-point measurements rather than dynamic biomarker profiling [14]

- Use of oversimplified model systems that don't capture human disease complexity [14]

- Lack of functional validation demonstrating biological relevance [14]

Solutions:

- Implement Longitudinal Sampling: Capture temporal biomarker dynamics through repeated measurements over time rather than single snapshots [14].

- Employ Human-Relevant Models: Utilize PDX, organoids, and 3D co-culture systems that better mimic human physiology [14].

- Conduct Functional Validation: Move beyond correlative evidence to demonstrate direct biological role in disease processes or treatment responses [14].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q: What strategies can improve the predictive validity of preclinical models?

A: Integrating human-relevant models and multi-omics profiling significantly increases clinical predictability [14]. Advanced platforms including patient-derived xenografts (PDX), organoids, and 3D co-culture systems better simulate the host-tumor ecosystem and forecast real-life responses [14]. Combining these with multi-omic approaches (genomics, transcriptomics, proteomics) helps identify context-specific, clinically actionable biomarkers that may be missed with single approaches.

Q: How can we address the high attrition rates in Phase 1 clinical trials?

A: Adopting data-driven strategies is crucial for reducing Phase 1 attrition. Trials should be designed as critical experiments with clear success/failure criteria rather than exploratory fact-finding missions [12]. Leveraging AI platforms that identify drug characteristics, patient profiles, and sponsor factors can design trials more likely to succeed [12]. Additionally, using real-world data to identify and match patients more efficiently to clinical trials helps adjust designs proactively [12].

Q: What are New Approach Methodologies (NAMs) and how do they improve translational accuracy?

A: NAMs include advanced in vitro systems, in silico mechanistic models, and computational techniques like AI and machine learning that improve translational success [11]. These human-relevant approaches reduce reliance on animal studies and provide better predictive data. Specific examples include physiologically based pharmacokinetic modeling, quantitative systems pharmacology applications, mechanistic modeling for drug-induced liver injury, and tumor microenvironment models [11].

Q: How can we balance speed and rigor in accelerated approval pathways?

A: The FDA's accelerated approval pathways require careful attention to confirmatory trial requirements, including target completion dates, evidence of "measurable progress," and proof that patient enrollment has begun [12]. While these pathways offer cost-saving opportunities, companies must balance speed with rigorous evidence generation, as failures in confirmatory trials (like Regeneron's CD20xCD3 bispecific antibody rejection) can further delay market entry [12].

Experimental Protocols & Workflows

Protocol 1: Longitudinal Biomarker Validation

Purpose: To capture dynamic biomarker changes over time rather than relying on single time-point measurements.

Materials:

- Appropriate biological model (PDX, organoids, 3D co-culture)

- Multi-omics profiling capabilities (genomic, transcriptomic, proteomic)

- Time-series experimental design framework

Procedure:

- Establish baseline biomarker measurements at time zero

- Administer experimental treatment according to predetermined schedule

- Collect samples at multiple predetermined time points (e.g., 24h, 48h, 72h, 1 week)

- Process samples using standardized multi-omics protocols

- Analyze temporal patterns and correlation with treatment response

- Validate findings using orthogonal methods

Validation Criteria: Biomarker changes should precede or coincide with functional treatment responses and show consistent patterns across biological replicates.

Protocol 2: Cross-Species Biomarker Translation

Purpose: To bridge biomarker data from preclinical models to human applications.

Materials:

- Data from multiple model systems (minimum of 2-3 different species/models)

- Cross-species transcriptomic analysis capabilities

- Functional assay platforms

Procedure:

- Profile biomarker expression/response in multiple model systems

- Perform cross-species computational integration to identify conserved patterns

- Conduct functional assays to confirm biological relevance across systems

- Validate findings in human-derived samples or models

- Establish correlation coefficients between model predictions and human responses

Validation Criteria: Biomarkers showing consistent patterns across species and correlation with human data have higher translational potential.

Visualization of Workflows

Diagram 1: Drug Discovery Translational Pipeline

Diagram 2: Biomarker Translation Strategy

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Research Materials for Improved Translation

| Research Tool | Function | Application in Addressing Translational Gaps |

|---|---|---|

| Patient-Derived Xenografts (PDX) | Better recapitulate human tumor characteristics and evolution compared to conventional cell lines [14] | Biomarker validation, preclinical efficacy testing |

| 3D Organoid Systems | 3D structures that retain characteristic biomarker expression and simulate host-tumor ecosystem [14] | Personalized medicine, therapeutic response prediction |

| Multi-Omics Platforms | Integrate genomic, transcriptomic, and proteomic data to identify context-specific biomarkers [14] | Comprehensive biomarker discovery, pathway analysis |

| TR-FRET Assay Systems | Time-resolved fluorescence energy transfer for protein interaction and compound screening studies [15] | High-throughput screening, binding assays |

| AI/ML Predictive Platforms | Identify patterns in large datasets to predict clinical outcomes from preclinical data [12] [14] | Trial optimization, patient stratification, biomarker discovery |

| Microphysiological Systems (Organs-on-Chips) | Human-relevant in vitro systems that mimic organ-level functionality [11] | Toxicity testing, ADME profiling, disease modeling |

Addressing the persistent challenge of high attrition rates and failed translations in drug discovery requires a fundamental shift in approach. By implementing human-relevant model systems, robust validation frameworks, and data-driven decision processes, researchers can bridge the critical materials gap between preclinical promise and clinical utility. The troubleshooting guides and methodologies presented here provide actionable strategies to enhance translational success, ultimately accelerating the development of effective therapies for patients in need.

The "transformation gap" in microfluidics describes the significant challenge in translating research findings into large-scale commercialized products [16]. This gap is often exacerbated by a "materials gap," where idealized model systems used in research fail to capture the complexities of real-world components and operating environments [1]. This technical support center provides targeted troubleshooting guides and FAQs to help researchers and drug development professionals overcome common experimental hurdles, thereby bridging these critical gaps in microfluidic commercialization.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

What does "zero dead volume" mean in microvalves and why is it critical? Zero dead volume means no residual liquid remains in the flow path after operation. This is crucial for reducing contamination between different liquids, especially in sensitive biological applications where even minimal cross-contamination can compromise results. This precision is achieved through highly precise machining of materials like PTFE and PCTFE [17].

My flow sensor shows constant value fluctuations. What is the likely cause? This typically occurs when a digital flow sensor is incorrectly declared as an analog sensor in your software. Remove the sensor from the software and redeclare it with the correct digital communication type. Note that instruments like the AF1 or Sensor Reader cannot read digital flow sensors [18].

How can I prevent clogging in my microfluidic system? Always filter your solutions before use, as unfiltered solutions are a primary cause of sensor and channel clogging. For existing clogs, implement a cleaning protocol using appropriate solvents like Hellmanex or Isopropanol (IPA) at sufficiently high pressure (minimum 1 bar) [18].

My flow rate decreases when I increase the pressure. What is happening? You are likely operating outside the sensor's functional range. The real flow rate may exceed the sensor's maximum capacity. Use the tuning resistance module if your system has one, or add a fluidic resistance to your circuit and test the setup again [18].

Which materials offer the best chemical resistance for valve components? PTFE (Polytetrafluoroethylene) is chemically inert and offers high compatibility with most solvents. PCTFE (Polychlorotrifluoroethylene) is chosen for valve seats due to its exceptional chemical resistance and durability in demanding applications [17].

Troubleshooting Guides

Flow Sensor Issues

Problem: Flow sensor is not recognized by the software.

- Check Power and Connection: Ensure the host instrument (e.g., OB1) is powered on and check the power button. Verify all cables and microfluidic connections match the user guide specifications [18].

- Verify Sensor Type in Software: When adding the sensor, declare the correct type (digital or analog) as per your order. A mismatch can cause recognition or fluctuation issues [18].

- Check Instrument Compatibility: Confirm that your instrument (e.g., OB1, AF1) is compatible with the type of flow sensor you are using (digital/analog) [18].

Problem: Unstable or non-responsive flow control.

- Check Tightening: Inspect and ensure all tubing connectors are properly tightened, as loose fittings can cause instability [18].

- Adjust PID Parameters:

- Non-responsive flow: Default or too-low PID parameters can cause delays. Increase the PID parameters for a more responsive flow control mode [18].

- Unstable flow: Use the software's "Regulator" mode. If the flow stabilizes, adapt your microfluidic circuit's total resistance and/or fine-tune the PID parameters [18].

- Re-add Sensor: If instability persists in "Regulator" mode, remove the sensor from the software and add it again, carefully selecting the correct analog/digital mode, channel, and sensor model [18].

Device and Protocol Errors

Problem: Pressure leakage or control error in liquid handlers.

This error often indicates a poor seal. Check the following:

- Source Wells: Ensure all source wells are fully seated in their positions and the protocol uses a plate with a sufficient number of wells [19].

- Alignment: Verify the dispense head channels and source wells are correctly aligned in the X/Y direction. Misalignment may require support assistance [19].

- Distance: The dispense head should be about 1 mm from the source plate. Check for tilting [19].

- Hardware Damage: Inspect the head rubber for damage (cuts, rips) and listen for any whistling sounds indicating a leaking seal. Contact support if found [19].

Problem: Droplets landing out of position in liquid handlers.

- Test and Identify Shift: Dispense deionized water from source wells A1 and H12 to the center and four corners of a target plate. Observe if the error is consistent (e.g., all droplets shift left) [19].

- Check for Well-Specific Issues: Flip the source well 180 degrees and repeat the run. If the droplet direction changes, the issue may be with the source well itself [19].

- Adjust Target Position: Access the software's advanced settings to find the "Move To Home" function and manually adjust the target tray position to compensate for the observed shift [19].

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Liquid Class Verification for Precision Dispensing

This protocol ensures reliable droplet dispensing, which is foundational for reproducible results in drug development and diagnostics [19].

1. Objective: To validate the accuracy of a custom liquid class by dispensing and measuring droplet consistency.

2. Materials & Reagents:

- I.DOT Liquid Handler with Assay Studio software [19].

- Compatible source plate (e.g., HT.60 or S.100) [19].

- Transparent, foil-sealed 1536-well target plate.

- Deionized water or the specific liquid to be verified.

- Lint-free swabs and 70% ethanol for cleaning [19].

3. Methodology:

- Preparation: Clean the DropDetection board and openings with 70% ethanol to prevent false readings [19].

- Liquid Loading: Fill each source well with a sufficient volume of liquid (>10 µL), ensuring no air bubbles are present [19].

- Protocol Setup: Create a protocol to dispense the target droplet volume (e.g., 500 nL) from each source well to its corresponding target well (A1 to A1, B1 to B1, etc.) [19].

- Execution & Repetition: Run the protocol and repeat it 3-5 times to gather sufficient data.

- Validation: The system's software will measure droplet consistency. The acceptance criterion is typically ≤1% of droplets not being detected [19].

Protocol 2: System Cleaning for Different Fluid Types

Preventing material degradation and carryover is critical for bridging the materials gap. This protocol outlines cleaning procedures for various fluids [20].

1. Objective: To effectively clean microfluidic sensors and channels after using different types of fluids, minimizing carryover and material incompatibility.

2. Materials & Reagents:

- Microfluidic flow sensor or system.

- Appropriate cleaning agents: Isopropanol (IPA), Denatured Alcohol, Hellmanex, or slightly acidic solutions (e.g., for water-based mineral deposits) [18] [20].

- Syringe or pressure system capable of delivering ≥1 bar pressure.

- 0.22 µm filters for pre-filtering solutions.

3. Methodology:

- General Principle: Never let the sensor dry out after use with complex fluids. Flush with a compatible cleaning agent shortly after emptying the system [20].

- Water-based Solutions: Regular flushing with DI water is recommended to prevent mineral build-up. For existing deposits, occasionally flush with a slightly acidic cleaning agent [20].

- Solutions with Organic Materials: Flush regularly with solvents like ethanol, methanol, or IPA to remove organic films formed by microorganisms [20].

- Silicone Oils: Use special cleaners recommended by your silicone oil supplier. Do not let the sensor dry out [20].

- Paints or Glues: These are critical. Immediately after use, flush with a manufacturer-recommended cleaning agent compatible with your system materials. Test the cleaning procedure before your main experiment [20].

- Alcohols or Solvents: These are generally low-risk. A short flush with IPA is usually sufficient for cleaning [20].

Research Reagent Solutions

The selection of materials and reagents is pivotal for creating robust and commercially viable microfluidic systems. The table below details key components and their functions.

| Item | Primary Function | Key Characteristics & Applications |

|---|---|---|

| PTFE (Valve Plugs) | Provides a seal and controls fluid flow. | Chemically inert, high compatibility with most solvents, excellent stress resistance [17]. |

| PEEK (Valve Seats) | Provides a durable sealing surface. | Outstanding mechanical and thermal properties, suitable for challenging microfluidic environments [17]. |

| PCTFE (Valve Seats) | Provides a durable and chemically resistant sealing surface. | Exceptional chemical resistance and durability, ideal for specific, demanding applications [17]. |

| UHMW-PE (Valve Plugs) | Provides a seal and withstands mechanical movement. | Exceptional toughness and the highest impact strength of any thermoplastic [17]. |

| I.DOT HT.60 Plate | Source plate for liquid handling. | Enables ultra-fine droplet control (e.g., 5.1 nL for DMSO) for high-throughput applications [19]. |

| I.DOT S.100 Plate | Source plate for liquid handling. | Provides high accuracy for larger droplet sizes (e.g., 10.84 nL), suitable for a wide range of tasks [19]. |

| Isopropanol (IPA) | System cleaning and decontamination. | Effective for flushing out alcohols, solvents, and organic materials; standard for general cleaning [18] [20]. |

| Hellmanex | System cleaning for clogs and organics. | A specialized cleaning detergent for removing tough organic deposits and unclogging channels [18]. |

Workflow and System Diagrams

Microfluidic Troubleshooting Logic

Liquid Class Verification Workflow

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

What is the "materials gap" in computational research? The materials gap refers to the significant difference between simplified model systems used in theoretical studies and the complex, real-world catalysts used in practice. Computational studies often use idealised models, such as single-crystal surfaces. In contrast, real catalysts are typically irregularly shaped particles distributed on high-surface-area materials [1] [2]. This gap can lead to inaccurate predictions if the model's limitations are not understood and accounted for.

What is the "pressure gap" and how does it relate to the materials gap? The pressure gap is another major challenge, alongside the materials gap. It describes the discrepancy between the ultra-high-vacuum conditions (very low pressure) under which many surface science techniques provide fundamental reactivity data and the high-pressure conditions of actual catalytic reactors. These different pressures can cause fundamental changes in mechanism, for instance, by making adsorbate-adsorbate interactions very important [2].

Why might the band gap of a material in the Materials Project database differ from my experimental measurements? Electronic band gaps calculated by the Materials Project use a specific method (PBE) that is known to systematically underestimate band gaps. This is a conscious choice to ensure a consistent dataset for materials discovery, but it is a key systematic error that researchers must be aware of. Furthermore, layered crystals may have significant errors in interlayer distances due to the poor description of van der Waals interactions by the simulation methods used [21].

Why do I get a material quantity discrepancy in my project schedules? Material quantity discrepancies often arise from unintended model interactions. For example, when a beam component intersects with a footing in a structural model, the software may automatically split the beam and assign it a material from the footing, generating a small, unexpected area or volume entry in the schedule. The solution is to carefully examine the model at the locations of discrepancy and adjust the design or use filters in the scheduling tool to exclude these unwanted entries [22].

I found a discrepancy between a material model's implementation in code and its theoretical formula. What should I do? Such discrepancies are not always errors. In computational mechanics, the implementation of a material model can legitimately differ from its theoretical formula when the underlying mathematical formulation changes. For example, the definition of the volumetric stress and tangent differs between a one-field and a three-field elasticity formulation. It is crucial to ensure that the code implementation matches the specific formulation (and its linearisation) used in the documentation or tutorial, even if it looks different from the general theory [23].

Troubleshooting Guide: Identifying and Bridging Gaps

This guide provides a structured methodology for researchers to diagnose and address common material and model disconnects.

Step 1: Identify the Nature of the Gap First, classify the discrepancy using the table below.

| Gap Type | Classic Symptoms | Common Research Areas |

|---|---|---|

| Materials Gap [1] [2] | Model system (e.g., single crystal) shows different activity/stability than real catalyst (e.g., nanoparticle). | Heterogeneous catalysis, nanocatalyst design. |

| Pressure Gap [2] | Reaction mechanism or selectivity changes significantly between ultra-high-vacuum and ambient or high-pressure conditions. | Surface science, catalytic reaction engineering. |

| Property Gap [21] | Calculated material property (e.g., band gap, lattice parameter) does not match experimental value, often in a systematic way. | Computational materials science, DFT simulations. |

| Implementation Gap [23] | Computer simulation results do not match theoretical expectations, or code implementation differs from a textbook formula. | Finite element analysis, computational physics. |

Step 2: Execute Root Cause Analysis Follow the diagnostic workflow below to pinpoint the source of the disconnect.

Step 3: Apply Corrective Methodologies Based on the root cause, implement one or more of the following protocols.

Protocol A: For Model Oversimplification (Bridging the Materials Gap)

- Objective: To move from idealized model systems to more realistic catalyst structures.

- Methodology: Perform Density Functional Theory (DFT) calculations using fully relaxed nanoparticle models that more accurately represent the size (<3 nm) and shape of real catalysts. Study properties like surface contraction and local structural flexibility, which are crucial at the nanoscale and are often ignored in simpler models [1].

- Validation: Compare the predicted stability and activity trends of the realistic nanoparticle model with experimental data on real catalyst systems.

Protocol B: For Parameter Optimization & Model Calibration

- Objective: To efficiently and accurately calibrate complex material model parameters against experimental data.

- Methodology: Implement a Differentiable Physics framework. This involves integrating finite element models into a differentiable programming framework to use Automatic Differentiation (AD). This method allows for direct computation of gradients, eliminating the need for inefficient finite-difference approximations [24].

- Validation: Benchmark the AD-enhanced method (e.g., Levenberg-Marquardt algorithm) against traditional gradient-free (Bayesian Optimization) and finite-difference methods. Success is demonstrated by a significant reduction in computational cost and improved convergence rate for calibrating parameters, for example, in an elasto-plastic model for 316L stainless steel [24].

Protocol C: For Systematic Calculation Error (Bridging the Property Gap)

- Objective: To understand and correct for systematic errors in computational data.

- Methodology: When using data from high-throughput databases (e.g., Materials Project), always consult the peer-reviewed publications associated with the property. These publications benchmark the calculated values against known experiments, providing an estimate of typical and systematic error [21].

- Validation: For lattice parameters, expect a possible over-estimation of 1-3%. For band gaps, expect a systematic underestimation. Adjust your interpretation of the data accordingly.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

The following table lists key computational and methodological "reagents" essential for designing experiments that can effectively bridge material and model gaps.

| Tool / Solution | Function in Analysis | Key Consideration |

|---|---|---|

| Differentiable Physics Framework [24] | Enables highly efficient, gradient-based calibration of complex model parameters using Automatic Differentiation (AD). | Superior to finite-difference and gradient-free methods in convergence speed and cost for high-dimensional problems. |

| Realistic Nanoparticle Model [1] | A computational model that accounts for precise size, shape, and structural relaxation of nanoparticles. | Essential for making valid comparisons with experiment at the nanoscale (< 3 nm); impacts stability and activity. |

| In Situ/Operando Study [2] | A technique to study catalysts under actual reaction conditions, bypassing the need for model-based extrapolation. | Provides direct information but may not alone provide atomistic-level insight; best combined with model studies. |

| Info-Gap Decision Theory (IGDT) [5] | A non-probabilistic framework for modeling severe uncertainty and making robust decisions. | Useful for modeling uncertainty in parameters like energy prices where probability distributions are unknown. |

| SERVQUAL Scale [5] | A scale to measure the gap between customer expectations and perceptions of a service. | An example of a structured gap model from marketing, illustrating the universality of gap analysis. |

Visualizing the Research Workflow: From Gap Identification to Resolution

The following diagram maps the logical workflow for a comprehensive research project aimed at resolving a materials-model disconnect, integrating the concepts and tools outlined above.

Bridging the Gap: Methodological Innovations and AI-Driven Solutions

Leveraging Advanced Prototyping and Gap System Prototypes for Rapid Iteration

What are the core stages of prototype development in materials research?

Prototype development follows a structured, iterative workflow that guides a product from concept to scalable production. The five key stages are designed to reduce technical risk and validate assumptions before major investment [25].

The 5-Stage Prototyping Workflow

| Stage | Primary Goal | Key Activities | Common Prototype Types & Methods |

|---|---|---|---|

| Stage 1: Vision & Problem Definition | Understand market needs and user pain points [25]. | Investigate user behavior, set product goals, define feature requirements [25]. | Concept sketches, requirement lists [25]. |

| Stage 2: Concept Development & Feasibility (POC) | Validate key function feasibility and build early proof-of-concept models [25]. | Brainstorming, concept screening, building cheap rapid prototypes (e.g., cardboard, foam, FDM 3D printing) [25]. | Proof-of-Concept (POC) functional prototype (often low-fidelity) [25] [26]. |

| Stage 3: Engineering & Functional Prototype (Alpha) | Convert concepts into engineering structures and verify dimensions, tolerances, and assembly [25]. | Material selection, tolerance design, FEA/CFD simulations. Building functional builds via CNC machining or SLS printing [25]. | Works-like prototype, Alpha prototype [25] [26]. |

| Stage 4: Testing & Validation (Beta) | User testing and performance validation under real-world conditions [25]. | Integrate looks-like and works-like prototypes. Conduct user trials, reliability tests, and environmental simulations [25]. | Beta prototype, integrated prototype, Test prototype (EVT/DVT) [25]. |

| Stage 5: Pre-production & Manufacturing | Transition from sample to manufacturing and optimize for production (DFM/DFA) [25]. | Small-batch trial production (PVT), mold testing, cost analysis, manufacturing plan finalization [25]. | Pre-production (PVT) prototype [25]. |

How can I systematically identify a "materials gap" in my model system?

A "materials gap" refers to the disparity between the ideal material performance predicted by computational models and the actual performance achievable with current synthesis and processing capabilities. Identifying this gap is a foundational step in model systems research [27] [28].

Methods for Identifying Research Gaps and Needs

| Method Category | Description | Application in Materials Research |

|---|---|---|

| Knowledge Synthesis [27] | Using existing literature and systematic reviews to identify where conclusive answers are prevented by insufficient evidence. | Analyzing systematic reviews to find material properties or synthesis pathways where data is conflicting or absent. |

| Stakeholder Workshops [27] | Convening experts (e.g., researchers, clinicians) to define challenges and priorities collaboratively. | Bringing together computational modelers, synthetic chemists, and application engineers to pinpoint translational bottlenecks. |

| Quantitative Methods [27] | Using surveys, data mining, and analysis of experimental failure rates to quantify gaps. | Surveying research teams on the most time-consuming or unreliable stages of material development. |

| Primary Research [27] | Conducting new experiments specifically designed to probe the boundaries of current understanding. | Performing synthesis parameter sweeps to map the real limits of a model's predictive power. |

Experimental Protocol: Gap Analysis for a Model Material System

- Define Best Practice (The Target): Establish the theoretical ideal based on foundational models or high-fidelity simulations. This answers "What should be happening?" in terms of material performance [28].

- Quantify Current Practice (The Reality): Conduct controlled synthesis and characterization of the target material. Measure key performance indicators (e.g., conductivity, strength, Tc) and synthesis yield. This answers "What is currently happening?" [28].

- Analyze the Discrepancy (The Gap): Formally state the gap. For example: "The predicted superconducting critical temperature (Tc) for the target cuprate is 110K, but our bulk synthesis consistently achieves a maximum of 85K with a 60% yield" [6].

- Identify Contributing Factors: Investigate the root cause. Is the gap due to:

Which prototyping technologies are most suitable for validating materials at different stages?

Choosing the right technology is critical for cost-effective and meaningful validation. The best tool depends on the stage of development and the key question you need to answer [25].

Technology Selection Guide

| Technology | Best For Prototype Stage | Key Advantages & Data Output | Materials Research Application |

|---|---|---|---|

| FDM 3D Printing [25] | Stage 2 (POC) | Lowest cost, fastest turnaround. Validates gross geometry and assembly concepts. | Printing scaffold or fixture geometries before committing to expensive material batches. |

| SLS / MJF 3D Printing [25] | Stage 2 (POC), Stage 3 (Alpha) | High structural strength, complex geometries without supports. Good for functional validation. | Creating functional prototypes of porous structures or complex composite layouts. |

| SLA 3D Printing [25] | Stage 1 (Vision), Stage 4 (Beta) | Ultra-smooth surfaces, high appearance accuracy. Ideal for aesthetic validation and demos. | Producing high-fidelity visual models of a final product for stakeholder feedback. |

| CNC Machining [25] | Stage 3 (Alpha), Stage 4 (Beta) | High precision (±0.01 mm), uses real production materials (metals, engineering plastics). | Creating functional prototypes that must withstand real-world mechanical or thermal stress. |

| Urethane Casting [25] | Stage 4 (Beta) | Low-cost small batches (10-50 pcs), surface finish close to injection molding. | Producing a larger set of samples for parallel user testing or market validation. |

| Digital Twin (Simulation) [25] | Prior to Physical Stage 3/4 | Reduces physical prototypes by 20-40%, predicts performance (stress, thermal, fluid dynamics). | Using FEA/CFD to simulate material performance in a virtual environment, predicting failure points. |

Our team is stuck – our prototype's experimental data consistently deviates from our model's predictions. How do we troubleshoot this?

This is a classic "materials gap" scenario. A structured approach to troubleshooting is essential to bridge the gap between computational design and experimental reality.

Troubleshooting Workflow: Bridging the Model-Experiment Gap

Key Reagent & Material Solutions for Gap Analysis

This table details essential materials and tools used in troubleshooting materials gaps.

| Reagent / Tool | Function in Troubleshooting |

|---|---|

| High-Purity Precursors | Ensures that deviations are not due to impurities from starting materials that can alter reaction pathways or final material composition. |

| Certified Reference Materials | Provides a known benchmark to calibrate measurement equipment and validate the entire experimental characterization workflow. |

| Computational Foundation Models [6] | Pre-trained models (e.g., on databases like PubChem, ZINC) can be fine-tuned to predict properties and identify outliers between your model and experiment. |

| Synchrotron-Grade Characterization | Techniques like high-resolution X-ray diffraction or XAS probe atomic-scale structure and local environment, revealing defects not captured in models. |

| In-situ / Operando Measurement Cells | Allows for material characterization during synthesis or under operating conditions, capturing transient states assumed in models. |

Detailed Methodology for Interrogating Experimental Process:

- Characterize at Atomic/Meso Scale: If your model predicts a perfect crystal structure but your prototype underperforms, use high-resolution characterization (e.g., TEM, atom probe tomography) to identify the root cause. Look for dislocations, grain boundaries, phase segregation, or unintended dopants that were not accounted for in the model [6].

- Audit Synthesis for Contamination/Defects: Systematically vary one synthesis parameter at a time (e.g., temperature, pressure, precursor injection rate) while holding others constant. This Design of Experiments (DoE) approach can identify a critical processing window where the model's predictions hold true, revealing the gap to be a process-control issue rather than a model flaw.

The Role of Digital Twins in Creating High-Fidelity Material and Biological Models

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

General Concepts

Q1: What is a Digital Twin in the context of material and biological research? A Digital Twin (DT) is a dynamic virtual replica of a physical entity (e.g., a material sample, a human organ, or a biological process) that is continuously updated with real-time data via sensors and computational models. This bidirectional data exchange allows the DT to simulate, predict, and optimize the behavior of its physical counterpart, bridging the gap between idealized models and real-world complexity [29] [30].

Q2: How do Digital Twins help address the "materials gap" in model systems research? The "materials gap" refers to the failure of traditional models (e.g., animal models or 2D cell cultures) to accurately predict human physiological and pathological conditions due to interspecies differences and poor biomimicry. DTs address this by creating human-based in silico representations that integrate patient-specific data (genetic, environmental, lifestyle) and multi-scale physics, leading to more clinically relevant predictions for drug development and personalized medicine [31] [30].

Technical Implementation

Q3: What are the core technological components needed to build a Digital Twin? Building a functional DT requires the integration of several core technologies [30]:

- Internet of Things (IoT) Sensors: For real-time data collection from the physical entity.

- Cloud Computing: To provide the computational power and data storage for hosting and updating the twin.

- Artificial Intelligence (AI) and Machine Learning (ML): To analyze data, identify patterns, and enable predictive simulations.

- Data and Communication Networks: To ensure seamless, bidirectional data flow.

- Modeling and Simulation Tools: Including both physics-based and data-driven models to represent system behavior.

Q4: What is the difference between a "sloppy model" and a "high-fidelity" Digital Twin? A "sloppy model" is characterized by many poorly constrained (unidentifiable) parameters that have little effect on model outputs, making accurate parameter estimation difficult. While such models can still be predictive, they may fail when pushed by optimal experimental design to explain new data [32]. A high-fidelity DT aims to overcome this through rigorous Verification and Validation (V&V). Verification ensures the computational model correctly solves the mathematical equations, while Validation ensures the model accurately represents the real-world physical system by comparing simulation results with experimental data [33].

Q5: What are common optimization methods used in system identification for Digital Twins? System identification, a key step in creating a DT, is often formulated as an inverse problem and solved via optimization. Adjoint-based methods are powerful techniques for this. They allow for efficient computation of gradients, enabling the model to identify material properties, localized weaknesses, or constitutive parameters by minimizing the difference between sensor measurements and model predictions [34].

Applications and Validation

Q6: How can Digital Twins improve the specificity of preclinical drug safety models? Specificity measures a model's ability to correctly identify non-toxic compounds. An overly sensitive model with low specificity can mislabel safe drugs as toxic, wasting resources and halting promising treatments. DTs, particularly those incorporating human organ-on-chip models, can be calibrated to achieve near-perfect specificity while maintaining high sensitivity. For example, a Liver-Chip model was dialed to 100% specificity, correctly classifying all non-toxic drugs in a study, while still achieving 87% sensitivity in catching toxic ones [35].

Q7: Can Digital Twins reduce the need for animal testing in drug development? Yes. DTs, especially when informed by human-derived bioengineered models (organoids, organs-on-chips), offer a more human-relevant platform for efficacy and safety testing. They can simulate human responses to drugs, helping to prioritize the most promising candidates for clinical trials and reducing the reliance on animal models, which often have limited predictivity for humans [36] [31].

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue 1: Poor Model Fidelity and High Prediction Error

Problem: Your Digital Twin's predictions consistently diverge from experimental observations, indicating low fidelity.

| Possible Cause | Diagnostic Steps | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Incorrect Model Parameters | Perform a sensitivity analysis to identify which parameters most influence the output. Check for parameter identifiability. | Use adjoint-based system identification techniques to calibrate material properties and boundary conditions against a baseline of experimental data [34]. |

| Overly Complex "Sloppy" Model | Analyze the eigenvalues of the Fisher Information Matrix (FIM). A sloppy model will have eigenvalues spread over many orders of magnitude [32]. | Simplify the model by fixing or removing irrelevant parameter combinations (those with very small FIM eigenvalues) that do not significantly affect the system's behavior. |

| Inadequate Model Validation | Check if the model was only verified but not properly validated. | Implement a rigorous V&V process. Compare model outputs (QoIs) against a dedicated set of experimental data not used in model calibration [33]. |

| Poor Quality or Insufficient Real-Time Data | Audit the data streams from IoT sensors for noise, drift, or missing data points. | Implement data cleaning and fusion algorithms. Increase sensor density or frequency if necessary to improve the data input quality [30]. |

Issue 2: Computational Intractability in Real-Time Simulation

Problem: The high-fidelity model is too computationally expensive to run for real-time or frequent updating of the Digital Twin.

| Possible Cause | Diagnostic Steps | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| High-Fidelity Model is Too Detailed | Profile the computational cost of different model components. | Develop a Reduced-Order Model (ROM) or a Surrogate Model. These are simplified, goal-oriented models that capture the essential input-output relationships of the system with far less computational cost [37]. |

| Inefficient Optimization Algorithms | Monitor the convergence rate of the system identification or parameter estimation process. | Employ advanced first-order optimization algorithms (e.g., Nesterov accelerated gradient) combined with sensitivity smoothing techniques like Vertex Morphing for faster and more stable convergence [34]. |

| Full-Order Model is Not Amortized | The model is solved from scratch for each new data assimilation step. | Use amortized inference techniques, where a generative model is pre-trained to directly map data to parameters, bypassing the need for expensive iterative simulations for each new case [37]. |

Issue 3: Failure to Generalize Across Experimental Conditions

Problem: The Digital Twin performs well under the conditions it was trained on but fails to make accurate predictions for new scenarios or patient populations.

| Possible Cause | Diagnostic Steps | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Lack of Representative Data | Analyze the training data for diversity. Does it cover the full range of genetic, environmental, and clinical variability? | Generate and integrate synthetic virtual patient cohorts using AI and deep generative models. This augments the training data to better reflect real-world population diversity [38]. |

| Model Bias from Training Data | Check if the model was built using data from a narrow subpopulation (e.g., a single cell line or inbred animal strain). | Build the DT using human-derived models like organoids or organs-on-chips, which better capture human-specific biology and genetic heterogeneity [31]. Validate the model against data from diverse demographic groups. |

Experimental Protocols for Key Applications

Protocol 1: Establishing a High-Fidelity Digital Twin for a Bioengineered Tissue

Objective: To create and validate a dynamic DT for a human liver tissue model to predict drug-induced liver injury (DILI).

Materials:

- Emulate Liver-Chip or equivalent organ-on-chip system [35].

- Human primary hepatocytes or iPS-cell derived hepatocytes.

- Perfusion bioreactor system with integrated sensors (pH, O2, metabolites).

- RNA/DNA sequencing tools for genomic profiling.

- High-performance computing (HPC) infrastructure.

Methodology:

- Physical Twin Characterization:

- Seed the Liver-Chip with human cells to form a 3D, physiologically relevant tissue.

- Continuously monitor and record tissue health and function parameters (e.g., albumin production, urea synthesis, ATP levels) to establish a baseline.

- Perform genomic, proteomic, and metabolomic profiling to define the initial state.

Digital Twin Seeding & Workflow:

- Agent 1 (Geometry): Digitize the 3D geometry of the tissue construct from CAD or imaging data [29].

- Agent 2 (Material Properties): Input scaffold material properties and initial cell distribution into the model.

- Agent 3 (Behavioral Model): Formulate a multi-scale model integrating cellular kinetics, metabolic pathways, and fluid dynamics. Use parameters from the physical twin characterization.

- Update Knowledge Graph: Seed a dynamic knowledge graph with all initial parameters, model definitions, and experimental baseline data [29].

Validation and Calibration:

- Step 1: Verification. Ensure the computational model solves the equations correctly by comparing with analytical solutions [33].

- Step 2: Internal Validation. Expose the physical liver chip to a training set of compounds (known toxic and safe). Update the DT's parameters (e.g., metabolic rate constants) using adjoint-based optimization to minimize the difference between simulated and observed tissue responses [34].

- Step 3: External Validation. Challenge the system with a blinded test set of novel compounds. Assess the DT's predictive accuracy for DILI using sensitivity and specificity metrics [35].

The workflow for this protocol is summarized in the diagram below:

Diagram Title: Digital Twin Workflow for a Liver-Chip Model

Protocol 2: Using a Digital Twin as a Synthetic Control in a Clinical Trial

Objective: To augment a Randomized Controlled Trial (RCT) by creating digital twins of participants to generate a synthetic control arm, reducing the number of patients needing placebo.

Materials:

- Patient data (EHRs, genomics, imaging, wearables).

- AI-based deep generative models.

- High-performance computing cluster.

- Clinical trial management software.

Methodology:

- Virtual Patient Generation:

- Collect comprehensive baseline data from real trial participants.

- Use AI models trained on historical control datasets and real-world evidence to generate a library of synthetic virtual patient profiles that reflect the target population's diversity [38].

Digital Twin Synthesis:

- For each real participant in the experimental arm, create a matched digital twin.

- Simulate the disease progression and standard care response in these digital twins to create a "synthetic control arm" [38].

Trial Execution and Analysis:

- Administer the investigational drug to the real participants.

- Compare the outcomes of the real treatment group against the outcomes predicted for their digital twins under the control condition.

- Use statistical methods to assess the treatment effect, leveraging the increased power provided by the synthetic cohort.

The logical relationship of this protocol is shown below:

Diagram Title: Digital Twins as Synthetic Controls in Clinical Trials

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

The following table details key materials and technologies essential for developing Digital Twins in material and biological research.

| Item | Function/Application | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| Organ-on-Chip (OoC) Systems | Microfluidic devices that emulate the structure and function of human organs; provide a human-relevant, perfused physical twin for data generation. | Liver-Chip for predicting drug-induced liver injury (DILI) with high specificity [31] [35]. |

| Organoids | 3D self-organizing structures derived from stem cells that mimic key aspects of human organs; used for high-throughput screening and disease modeling. | Patient-derived tumor organoids for personalized drug sensitivity testing and DT model calibration [31]. |

| Adjoint-Based Optimization Software | Computational tool that efficiently calculates gradients for inverse problems; crucial for calibrating model parameters to match experimental data. | Identifying localized weaknesses or material properties in a structural component or biological tissue from deformation measurements [34]. |

| Reduced-Order Models (ROMs) | Simplified, computationally efficient surrogate models that approximate the input-output behavior of a high-fidelity model. | Enabling real-time simulation and parameter updates in a Digital Twin where the full-order model is too slow [37]. |

| Dynamic Knowledge Graph | A graph database that semantically links all entities and events related to the physical and digital twins; serves as the DT's "memory" and self-model. | Encoding the evolving state of a building structure or a patient's health record, allowing for complex querying and reasoning [29]. |

AI and Machine Learning for Predictive Material Property and Behavior Modeling

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Data and Modeling Challenges

Q1: How can I improve my model's performance when I have very limited experimental data?

- A: Leverage meta-learning techniques like Extrapolative Episodic Training (E2T), which trains a model on a large number of artificially generated extrapolative tasks. This allows the model to "learn how to learn" and achieve higher predictive accuracy, even for materials with features not present in the limited training data [39]. Furthermore, embed existing expert knowledge into the model. For example, the ME-AI framework uses a chemistry-aware kernel in a Gaussian-process model and relies on expert-curated datasets and labeling based on chemical logic to guide the learning process effectively with a relatively small dataset [40].

Q2: My model performs well on training data but fails to generalize to new, unseen material systems. What can I do?

- A: This is a classic problem of interpolation vs. extrapolation. The E2T algorithm is specifically designed for domain generalization, helping models acquire the ability to make reliable predictions beyond the distribution of the training data [39]. Additionally, ensure your training dataset is diverse and representative of the chemical and structural space you intend to explore. Techniques like data augmentation, while more common in image processing, can be adapted by incorporating physical knowledge or using generative models to create realistic synthetic data points [39].

Q3: How can I make a "black box" machine learning model's predictions interpretable to guide experimental synthesis?

- A: Prioritize models that offer inherent interpretability. The ME-AI framework uses a Dirichlet-based Gaussian-process model to uncover quantitative, human-understandable descriptors (like the "tolerance factor" and hypervalency) that are predictive of material properties. This articulates the latent expert insight in a form that researchers can use for targeted synthesis [40]. For complex models, employ post-hoc explanation tools (like SHAP or LIME) to identify which features were most influential for a given prediction.

Q4: How do I know if a predicted material can be successfully synthesized?

- A: Machine learning can guide synthesis, but validation remains key. Integrate process-structure-property (PSP) relationships into your AI framework. For instance, comprehensive AI-driven frameworks can not only predict properties but also inversely design optimal process parameters (e.g., nanoparticle diameters for nanoglass) to achieve a desired microstructure and property [41]. Ultimately, these AI-generated synthesis protocols must be coupled with rapid experimental validation in a closed-loop system [42].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: Inability to predict rare events (e.g., material failure).

- Symptoms: Model consistently misses the occurrence of infrequent but critical events, such as abnormal grain growth.

- Solution:

- Use Temporal and Relational Models: Combine a Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) network to model the evolution of material properties over time with a Graph Convolutional Network (GCN) to establish relationships between different components (e.g., grains) [43] [44].

- Align on the Event: Work backward from the rare event to identify precursor trends. Analyze the properties of grains at 10 million time steps before failure versus 40 million steps to find consistent, predictive signatures [43].

- Implementation: This approach has been shown to predict abnormal grain growth with 86% accuracy within the first 20% of the material's simulated lifetime, allowing for early detection and intervention [43] [44].

Problem: Model predictions are inaccurate for complex, multi-phase, or grained materials.

- Symptoms: Poor performance when predicting properties for materials with heterogeneous microstructures like nanoglasses or polycrystalline alloys.

- Solution:

- Advanced Microstructure Quantification: Move beyond simple descriptors. Use novel characterization techniques like the Angular 3D Chord Length Distribution (A3DCLD) to capture spatial features of 3D microstructures in detail [41].

- Adopt a Comprehensive AI Framework: Implement a framework that integrates this detailed microstructure data with a Conditional Variational Autoencoder (CVAE). The CVAE enables robust inverse design, allowing you to explore multiple microstructural configurations that lead to a desired mechanical response [41].

- Validate Experimentally: Ensure the framework is validated against experimental data for key properties like elastic modulus and yield strength to confirm its predictive fidelity [41].

Problem: Computational cost of high-fidelity simulations (e.g., DFT) for generating training data is prohibitive.

- Symptoms: Inability to generate sufficient data for training accurate ML models due to time and resource constraints.

- Solution:

- Use Machine Learning Interpolated Potentials (MLIPs): Train ML models on a limited set of high-fidelity DFT simulations. The MLIP can then interpolate the potential field between these reference systems, dramatically reducing the computational cost for examining defects, distortions, and other variations [45].

- Leverage Existing Materials Databases: Bootstrap your research by using large-scale materials databases (e.g., Materials Project, AFLOW, OQMD) for initial model training and candidate screening [42].

- Hybrid Modeling: Combine the results of atomistic simulations with any available experimental data to create a hybrid model that predicts where new candidates might fall relative to known materials [45].

Experimental Protocols & Workflows

Protocol 1: ME-AI Workflow for Discovering Material Descriptors

This protocol outlines how to translate expert intuition into quantitative, AI-discovered descriptors for materials discovery [40].

- Curate a Specialized Dataset: An expert materials scientist curates a dataset focused on a specific class of materials (e.g., 879 square-net compounds). The priority is on measurement-based, experimentally accessible data.

- Define Primary Features (PFs): Select 12-15 atomistic and structural primary features believed to be relevant. These should be interpretable and could include:

- Electron affinity

- Pauling electronegativity

- Valence electron count

- FCC lattice parameter of the key element

- Key crystallographic distances (e.g.,

d_sq,d_nn)

- Expert Labeling: Label the materials based on the target property (e.g., topological semimetal). Use all available information:

- Visual comparison of experimental/computational band structures (56% of data).

- Chemical logic and analogy for alloys and related compounds (44% of data).

- Train a Chemistry-Aware Model: Train a Dirichlet-based Gaussian-process model with a chemistry-aware kernel on the curated dataset of PFs and labels.

- Extract Emergent Descriptors: The model will output a combination of primary features that form the most predictive descriptor(s), recovering known expert rules (e.g., tolerance factor) and potentially revealing new chemical levers (e.g., hypervalency).

Diagram 1: ME-AI descriptor discovery workflow.

Protocol 2: Predicting Rare Failure Events (Abnormal Grain Growth)

This protocol details the use of a combined deep-learning model to predict rare failure events like abnormal grain growth long before they occur [43] [44].

- Data Generation via Simulation: Conduct simulations of realistic polycrystalline materials to generate data on grain evolution over time under thermal stress.

- Feature Tracking Over Time: For each grain, track its properties (e.g., size, orientation, neighbor relationships) across millions of time steps.

- Temporal and Relational Modeling:

- Feed the time-series data of grain properties into a Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) network to capture temporal evolution patterns.

- Simultaneously, use a Graph Convolutional Network (GCN) to model the complex relationships and interactions between neighboring grains.

- Align on Failure Event: Identify the precise time step

T_failurewhen a grain becomes abnormal. Align the data from all abnormal grains backward from this point (T_failure - 10M steps,T_failure - 40M steps, etc.). - Identify Predictive Trends: Train the combined LSTM-GCN model to identify the shared trends in the evolving properties that consistently precede the abnormality.

- Validate Early Prediction: Test the model's ability to predict failure within the first 20% of the material's lifetime based on these early warning signs.

Diagram 2: Workflow for predicting rare failure events.

Quantitative Performance Data

Table 1: Performance Metrics of Featured AI/ML Models