Bridging the Pressure Gap in Catalysis: From Surface Science to Industrial and Biomedical Applications

This article provides a comprehensive overview of the long-standing 'pressure gap' challenge in catalysis, where fundamental surface science studies conducted in ultra-high vacuum (UHV) conditions fail to accurately predict catalyst...

Bridging the Pressure Gap in Catalysis: From Surface Science to Industrial and Biomedical Applications

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive overview of the long-standing 'pressure gap' challenge in catalysis, where fundamental surface science studies conducted in ultra-high vacuum (UHV) conditions fail to accurately predict catalyst behavior under industrially relevant high-pressure environments. We explore the latest technological advancements, including Ambient Pressure XPS (APXPS), graphene-separated membrane systems, and polarization-dependent infrared spectroscopy, that are bridging this divide. The content covers foundational concepts, cutting-edge methodologies, troubleshooting strategies, and validation frameworks, with a specific focus on implications for catalytic processes relevant to pharmaceutical development and biomedical research. By synthesizing insights from recent peer-reviewed studies and instrumental breakthroughs, this resource equips researchers with the knowledge to design more predictive experiments and develop efficient catalytic systems for drug synthesis and biomolecule production.

Understanding the Pressure Gap: The Fundamental Divide Between Surface Science and Applied Catalysis

Defining the Pressure and Materials Gaps in Heterogeneous Catalysis

In the field of heterogeneous catalysis, the journey from a fundamental laboratory discovery to an industrial-scale process is often hindered by two significant challenges known as the "pressure gap" and the "materials gap" [1]. These gaps describe the substantial differences between the well-controlled, simplified conditions of academic research and the complex, harsh environments of real-world industrial catalysis [1]. For researchers and drug development professionals, understanding and addressing these disparities is crucial for translating promising catalytic systems into practical applications, particularly within the context of resolving the pressure gap in catalysis research.

The pressure gap refers to the approximately 13 orders of magnitude difference in pressure between conventional surface science studies conducted under ultra-high vacuum (UHV) and industrial catalytic processes that typically operate at atmospheric pressure or higher [1]. The materials gap signifies the difference in complexity between single-crystal model catalysts used in fundamental studies and real industrial catalysts that consist of metallic nanoparticles on supports, often containing promoters, fillers, and binders [1]. This technical support document provides troubleshooting guidance and experimental methodologies to help researchers bridge these critical gaps in their catalytic investigations.

Understanding the Fundamental Gaps: FAQ

What exactly are the "pressure gap" and "materials gap" in heterogeneous catalysis?

The pressure gap describes the significant disparity (about 13 orders of magnitude) between the ultra-high vacuum conditions typically used in fundamental surface science studies and the atmospheric (or higher) pressure conditions of industrial catalytic processes [1]. The materials gap refers to the difference in complexity between the single-crystal model catalysts used in academic research and real-world catalysts that consist of metallic nanoparticles on supports, often containing promoters, fillers, and binders [1].

Why do these gaps pose such a significant problem in catalysis research?

These gaps are problematic because a catalyst's structure and chemical state can dramatically change between UHV and high-pressure conditions [1]. For instance, surface reconstruction, faceting, and oxidation phenomena occur under reaction conditions that are not observed in UHV, potentially leading to incorrect mechanistic conclusions and ineffective catalyst designs [1]. Many techniques that provide atomic-scale information about catalyst surfaces are limited to maximum pressures of 10⁻⁵ mbar and temperatures of 400 K, restricting their direct application under industrially relevant conditions [1].

What are the key consequences of neglecting these gaps in experimental design?

Failure to address these gaps can result in:

- Inaccurate mechanistic understanding of catalytic processes

- Development of catalysts that perform well under UHV but poorly at industrial conditions

- Inability to observe reaction-driven surface restructuring and faceting

- Overlooking the formation of surface species only stable under reaction conditions

- Poor translation of laboratory results to industrial applications [1]

Which industrial processes are most affected by these gaps?

Numerous industrially relevant systems are significantly affected, including:

- CO and NO oxidation over platinum catalysts

- NO reduction by H₂ on platinum

- Ammonia synthesis via the Haber-Bosch process

- Graphene growth on metal surfaces

- Sulfuric acid production via the contact process [2] [1]

Troubleshooting Guides for Gap-Related Experimental Challenges

Challenge: Discrepancy Between UHV and High-Pressure Results

Symptoms:

- Catalyst shows excellent activity in UHV but poor performance at atmospheric pressure

- Different reaction mechanisms observed between low and high-pressure regimes

- Surface characterization under UHV does not match surface state under reaction conditions

Possible Causes and Solutions:

| Cause | Solution | Experimental Approach |

|---|---|---|

| Surface reconstruction under reaction conditions [1] | Perform in situ characterization under realistic pressures | Utilize high-pressure STM, AFM, or surface X-ray diffraction |

| Formation of surface species only stable at high pressure [1] | Investigate catalyst under operando conditions | Employ techniques like PM-IRRAS or XPS adapted for higher pressures |

| Pressure-dependent oxidation states [1] | Monitor catalyst oxidation state during reaction | Implement X-ray absorption spectroscopy under working conditions |

Challenge: Disconnect Between Model and Real Catalysts

Symptoms:

- Single-crystal catalysts show different selectivity than nanoparticle systems

- Supported catalysts deactivate rapidly while model systems remain stable

- Promoter effects observed in industrial catalysts not replicated in model systems

Possible Causes and Solutions:

| Cause | Solution | Experimental Approach |

|---|---|---|

| Missing support effects in model systems [1] | Incorporate appropriate support materials in study | Design experiments with well-defined nanoparticles on relevant supports |

| Omission of promoters in simplified systems [3] | Include relevant promoters in catalyst design | Systematically study promoter effects using combinatorial approaches |

| Neglected mass transport limitations [3] | Account for diffusion constraints in catalyst design | Perform tortuosity measurements and design hierarchical pore structures |

Challenge: Characterization Limitations Under Reaction Conditions

Symptoms:

- Inability to determine active sites under working conditions

- Uncertainty about surface intermediates present during reaction

- Unknown structural changes during catalyst activation or deactivation

Possible Causes and Solutions:

| Cause | Solution | Experimental Approach |

|---|---|---|

| Lack of chemical sensitivity in microscopy techniques [1] | Combine multiple characterization methods | Correlate STM/AFM data with spectroscopic techniques (XPS, XAFS) |

| Limited spatiotemporal resolution in spectroscopy [4] | Implement time-resolved characterization | Use quick-XAS, modulation excitation spectroscopy, or operando TEM |

| Inability to probe liquid-solid interfaces [4] | Develop methods for liquid-phase catalysis | Apply ATR-IR spectroscopy, liquid-cell TEM, or sum frequency generation |

Advanced Experimental Protocols for Bridging the Gaps

Protocol: High-Pressure Scanning Tunneling Microscopy (HP-STM)

Principle: This technique enables direct observation of catalyst surface structure at the atomic scale under realistic pressure conditions, overcoming the pressure gap by allowing simultaneous imaging and activity measurements [1].

Experimental Workflow:

- Catalyst Preparation: Prepare well-defined single-crystal surfaces under UHV conditions (base pressure < 1 × 10⁻¹⁰ mbar)

- Reactor Isolation: Isolate the STM tip and sample in a miniature high-pressure cell (volume ~0.05 mL) while keeping the piezoelectric scanner in UHV

- Gas Introduction: Introduce reaction gases to pressures up to 1 bar using precision gas dosing systems

- Simultaneous Measurement:

- Acquire STM images with atomic resolution at elevated temperatures (up to 600 K)

- Monitor reaction products simultaneously using mass spectrometry of the effluent gas

- Data Correlation: Correlate structural changes in sequential STM images with catalytic activity measurements from mass spectrometry

Key Considerations:

- Use Kalrez O-rings for high-temperature seals (up to 600 K)

- Ensure minimal dead volume in the reactor cell for rapid gas exchange

- Implement quartz tuning forks for AFM operation where optical access is limited [1]

The relationship between technique capability and information obtained can be visualized as follows:

Protocol: In Situ Surface X-Ray Diffraction (SXRD)

Principle: Using high-energy X-rays at synchrotron facilities to probe catalyst structure under reaction conditions, bridging both pressure and materials gaps by investigating supported nanoparticles under realistic environments [1].

Experimental Workflow:

- Sample Design: Prepare model catalyst systems consisting of nanoparticles on flat supports or single crystals

- Reactor Cell: Utilize specially designed in situ reactors with X-ray transparent windows (e.g., Be, SiN membranes)

- Data Collection:

- Perform surface X-ray diffraction (SXRD) measurements during catalytic reaction

- Conduct grazing-incidence small-angle X-ray scattering (GISAXS) to monitor nanoparticle morphology

- Measure X-ray reflectivity for surface structure information

- Activity Correlation: Simultaneously monitor reaction rates using mass spectrometry or gas chromatography

- Data Analysis: Extract structural parameters (surface roughness, layer distances, particle sizes) and correlate with catalytic performance

Application Example: NO reduction by H₂ over platinum - SXRD revealed surface restructuring and faceting under reaction conditions that were not observed in UHV studies [1].

Protocol: Integrated Spectro-Microscopic Characterization

Principle: Combining multiple characterization techniques to overcome individual limitations, particularly addressing the materials gap by providing both structural and chemical information across different length scales [4].

Experimental Workflow:

- Multi-technique Setup: Design experimental systems that combine:

- Scanning probe microscopy (STM/AFM) for structural information

- X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) for chemical state analysis

- Polarization-modulation IR reflection absorption spectroscopy (PM-IRRAS) for surface species identification

- Simultaneous Data Acquisition: Coordinate measurements to obtain complementary information on the same catalyst under identical conditions

- Spatial Correlation: Map structural features to chemical composition at the nanoscale

- Temporal Resolution: Monitor dynamic processes during catalytic reactions with appropriate time resolution

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

The following table details key materials and their functions in advanced catalysis research aimed at bridging the pressure and materials gaps:

| Research Material | Function & Application | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Platinum Single Crystals [1] | Model catalysts for fundamental surface science studies | Various crystal facets (Pt(111), (110), (100)) exhibit different catalytic properties |

| Vanadium(V) Oxide (V₂O₅) [2] | Industrial catalyst for sulfuric acid production (contact process) | Preferred over Pt due to resistance to arsenic impurities in sulfur feedstock |

| Iron-Based Catalysts [2] | Ammonia synthesis via Haber-Bosch process | Contains promoters (Al₂O₃, K₂O) for enhanced activity and stability |

| Zeolite ZSM-5 [5] | Shape-selective catalyst for petroleum refining | Microporous structure provides size and shape selectivity for molecules |

| Quartz Tuning Forks [1] | Sensors for non-optical AFM detection in high-pressure environments | Enable AFM operation in reactors without optical access |

| Molten Copper Substrates [1] | Unique catalyst for graphene growth with fluid surface | Enables production of large single-crystalline graphene sheets |

| Kalrez/Viton O-rings [1] | High-temperature seals for reactor STM/AFM systems | Withstand temperatures up to 600 K under reactive atmospheres |

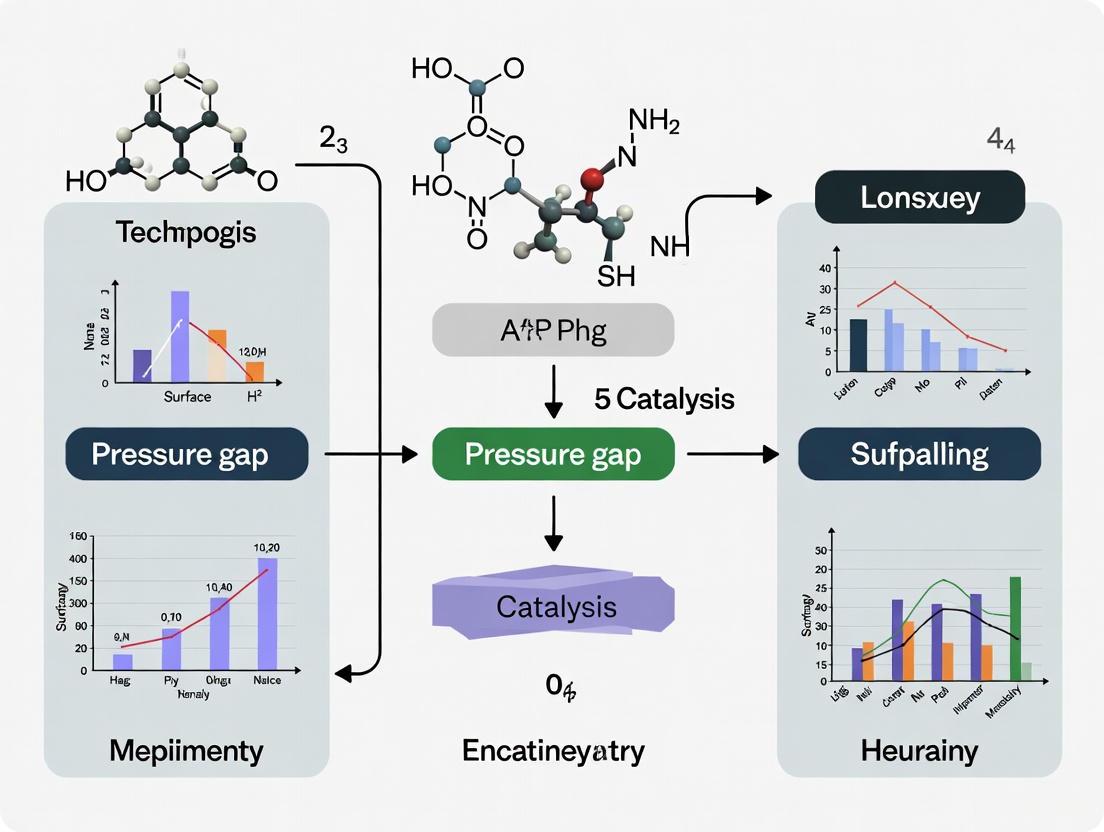

Interrelationship Between Experimental Approaches

Successfully bridging the pressure and materials gaps requires an integrated approach that combines multiple techniques and methodology considerations. The following diagram illustrates how different experimental strategies interrelate to address these challenges:

Frequently Asked Questions on Advanced Concepts

What is the Sabatier principle and how does it relate to these gaps?

The Sabatier principle states that optimal catalytic activity requires an intermediate strength of reactant adsorption - too weak and activation doesn't occur, too strong and products don't desorb [3]. This principle manifests differently across the pressure and materials gaps because adsorption strengths can change dramatically with pressure and catalyst nanostructure, explaining why a catalyst optimized under UHV may perform poorly at industrial conditions [3].

How do coherent, semicoherent, and incoherent interfaces affect catalytic performance?

Interface coherence significantly impacts surface energy and catalytic properties [3]:

- Coherent interfaces (perfect lattice matching) have low surface energy (0-200 mJ·m⁻²) and specific adsorption properties

- Semicoherent interfaces (partial matching) have medium surface energy (200-500 mJ·m⁻²)

- Incoherent interfaces (no lattice matching) have high surface energy (500-1000 mJ·m⁻²) These nanoscale "jumps" in surface energy strongly affect how reactants, intermediates, and products interact with the catalyst surface, contributing to the materials gap [3].

What role do machine learning and computational methods play in bridging these gaps?

Machine learning approaches are increasingly valuable for predicting nanoparticle catalytic activity and stability, which would be computationally prohibitive using first-principles calculations alone [4]. These methods can help extrapolate from model systems to real catalysts and from UHV to high-pressure conditions by identifying descriptor relationships that span the pressure and materials gaps [4].

How can we study catalyst deactivation mechanisms across these gaps?

Studying deactivation requires specialized approaches:

- Accelerated aging tests under realistic conditions

- Post-mortem analysis using surface science techniques

- In situ monitoring of structural changes during operation

- Theoretical modeling of sintering, coking, and poisoning mechanisms True understanding requires correlating deactivation phenomena observed industrially with fundamental processes studied at the atomic scale [3].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What is the "Pressure Gap" in catalysis research? The pressure gap refers to the significant challenge in comparing results from catalytic surface studies conducted under Ultra-High Vacuum (UHV) conditions—typically between 10⁻⁷ and 10⁻¹² mbar—with the performance of catalysts operating at industrial conditions, which are often at atmospheric pressure (around 1 bar) or higher [6] [7] [8]. This orders-of-magnitude difference in pressure can lead to dramatically different catalyst behavior, making it difficult to predict real-world performance from foundational UHV studies [7].

Q2: Why is there a "Materials Gap" alongside the Pressure Gap? The materials gap arises from the difference in complexity between the model catalysts used in fundamental research and industrial catalysts. Surface science often uses well-defined, clean single-crystals to understand basic mechanisms. In contrast, real-world industrial catalysts are complex, heterogeneous materials whose active sites can be influenced by supports, promoters, and the reaction environment itself [7]. Bridging both gaps is essential for translating fundamental knowledge into practical applications.

Q3: What are the main technical challenges of working with UHV systems? Creating and maintaining UHV environments requires meticulous attention to several factors [6] [8]:

- Outgassing: The release of trapped gases from chamber walls and internal components is a major gas load. This is managed by using low-outgassing materials (like certain stainless steels), minimizing internal surface area, and performing bake-outs (heating the entire chamber) to drive off volatiles [6] [8] [9].

- Pump Selection: Achieving UHV requires a combination of pumps, often a roughing pump paired with a high-vacuum pump like a Turbomolecular Pump (TMP) or an Ion Getter Pump (IGP) [6] [8].

- Conductance: Every component in the vacuum line limits gas flow. Optimizing conductance—the measure of how easily gas flows through the system—is critical for achieving the best possible base pressure and pump-down speed [6].

Q4: Are there experimental techniques that can operate across the pressure gap? Yes, the development of in situ and operando techniques is key to closing this gap. These methods allow for the observation of the catalyst surface under realistic reaction conditions. One innovative approach uses a graphene membrane to separate a high-pressure reaction cell from the UHV environment of an X-ray Photoelectron Spectroscopy (XPS) instrument. This enables the use of powerful surface-sensitive techniques to study catalysts at atmospheric pressure and above [10].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem 1: Inconsistent Catalytic Performance Between UHV and High-Pressure Testing

| Potential Cause | Diagnostic Steps | Recommended Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Adsorbate Coverage Differences | Perform Temperature-Programmed Desorption (TPD) at both pressure regimes to compare surface species. | Use in situ spectroscopy to identify the active surface phase under reaction conditions and adjust the model accordingly [7]. |

| Presence of "Spectator" Species | Use a technique like Ambient-Pressure XPS to identify non-reactive species blocking active sites at high pressure. | Factor in the effect of surface coverage on the reaction mechanism when building kinetic models [7]. |

| Unaccounted For Bulk Diffusion | Compare reaction rates on single crystals vs. nanoparticulated catalysts of the same material. | Design model systems that incorporate aspects of real catalysts, such as supported nanoparticles, for more relevant testing [7]. |

Problem 2: Inability to Reach or Maintain UHV Conditions

| Potential Cause | Diagnostic Steps | Recommended Solution |

|---|---|---|

| High Virtual Leak or Outgassing | Isolate sections of the vacuum system with valves to locate the problematic area. Use a Residual Gas Analyzer (RGA) to identify the gas species. | Perform a standard bake-out protocol (typically 100-200°C for several hours) to accelerate outgassing. Use components with low-outgassing rates and metallic seals [6] [8] [9]. |

| Actual Vacuum Leak | Use an RGA to look for a dominant peak (e.g., mass 4 for helium, mass 18 for water). Use a helium mass spectrometer leak detector. | Check seals and flanges. Re-tighten ConFlat flanges to the specified torque. For small leaks, professional repair or replacement of the faulty component may be necessary. |

| Insufficient Pumping Speed/Capacity | Check pump performance curves and compare to the system's total gas load and volume. | Ensure the pump combination (e.g., fore pump + TMP) is correctly sized for the chamber. Reduce conductance losses by using wider, shorter piping [6] [11]. |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Validating a Model Catalyst Across the Pressure Gap

This protocol outlines a systematic approach to verify that mechanistic insights gained from UHV studies are applicable at industrially relevant pressures, using the oxidative coupling of methanol as a historical example [7].

1. Objective: To determine if the reaction mechanism and selectivity observed on a single-crystal model catalyst in UHV are preserved at higher pressures.

2. Materials and Equipment:

- UHV Chamber System equipped with Low-Energy Electron Diffraction (LEED), XPS, and a Mass Spectrometer for gas analysis.

- High-Pressure Flow Reactor with online Gas Chromatograph (GC) for product analysis.

- Model Catalyst: A well-defined single crystal (e.g., Au(110)).

- Nanoparticulated Catalyst: A realistic catalyst analogous to the model (e.g., nanoporous Ag₀.₀₃Au₀.₉₇).

3. Step-by-Step Methodology:

- Step 1: UHV Kinetic Analysis

- Prepare a clean single-crystal surface in the UHV chamber via sputtering and annealing.

- Expose the crystal to controlled doses of reactants at low temperature (~200 K).

- Use temperature-programmed reaction spectroscopy (TPRS) to monitor the formation of reaction products and determine the reaction mechanism and activation barriers.

- Step 2: High-Pressure Reactor Testing

- Load the nanoparticulated catalyst into the high-pressure flow reactor.

- Run the reaction at industrially relevant conditions (e.g., 425 K, 1 bar) with a continuous flow of reactants.

- Use online GC to quantitatively measure the reaction rate and product selectivity.

- Step 3: Data Comparison and Model Validation

- Compare the product distribution (selectivity) from the high-pressure reactor with the products observed in the UHV TPRS experiments.

- Use the kinetic parameters (activation energies, reaction orders) obtained in UHV to mathematically model the expected output at high pressure.

- Validation Criterion: A successful validation is achieved if the predicted selectivity from the UHV-derived model matches the experimentally measured selectivity in the high-pressure reactor [7].

Protocol 2:In SituSurface Analysis Using a Graphene Membrane

This protocol describes a novel method to study catalysts at high pressure using XPS, bridging the pressure gap with a graphene separation layer [10].

1. Objective: To perform X-ray Photoelectron Spectroscopy on a catalyst sample under atmospheric pressure conditions.

2. Materials and Equipment:

- Atmospheric-Pressure XPS System with a specialized sample holder.

- Silicon Nitride Membrane with an array of micrometre-sized holes.

- Bilayer Graphene transferred to seal the holes in the silicon nitride membrane.

- Catalyst nanoparticles (e.g., Iridium, Copper, or Pd Black).

3. Step-by-Step Methodology:

- Step 1: Sample Preparation

- Synthesize or purchase the catalyst nanoparticles.

- Deposit the catalyst nanoparticles directly onto the graphene membrane window.

- Step 2: System Setup

- Mount the sample holder with the catalyst/graphene membrane into the AP-XPS instrument.

- The graphene membrane acts as a barrier, separating the UHV environment of the electron analyzer from the high-pressure reaction cell.

- Step 3: In Situ Measurement

- Introduce the reactant gases (e.g., O₂, H₂) into the reaction cell at atmospheric pressure.

- Direct X-rays through the graphene membrane onto the catalyst sample.

- Measure the kinetic energy of the electrons emitted from the catalyst surface through the graphene window. The graphene is thin enough to allow electrons to pass through with minimal energy loss, enabling chemical state analysis [10].

Diagram 1: Workflow for Validating a Model Catalyst.

Diagram 2: Graphene Membrane for AP-XPS.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents & Materials

The following table details essential materials and equipment for conducting experiments aimed at bridging the pressure gap.

| Item | Function & Importance in Pressure Gap Research |

|---|---|

| Well-Defined Single Crystals | Serve as model catalysts to establish fundamental reaction mechanisms without the complexity of real-world materials. They are the starting point for UHV surface science [7]. |

| Graphene Bilayer Membranes | Act as a transparent, electron-permeable window that physically separates a high-pressure reaction environment from a UHV analyzer, enabling in situ spectroscopy [10]. |

| Residual Gas Analyzer (RGA) | A mass spectrometer used to identify and quantify partial pressures of gases in a vacuum system. Critical for leak detection, monitoring contamination, and understanding the vacuum environment [8]. |

| Turbomolecular Pump (TMP) | A high-vacuum pump that uses rapidly spinning blades to momentum-transfer gas molecules. Essential for achieving and maintaining the UHV conditions required for surface-sensitive analysis [6] [8]. |

| Metallic Seals (e.g., Copper Gaskets) | Used in ConFlat and other UHV flanges to provide a hermetic, ultra-clean seal that can withstand high-temperature bake-out cycles, minimizing outgassing and leaks [6] [9]. |

Limitations of Traditional Surface Science Techniques (XPS, LEED, HREELS) in UHV

Frequently Asked Questions

1. What is the "pressure gap" in catalysis research? The pressure gap refers to the significant disparity between the ultrahigh vacuum (UHV) conditions (typically below 10⁻⁶ mbar) required for many traditional surface science techniques and the ambient or high-pressure conditions (often 1 bar or more) under which real-world catalytic reactions occur. The properties and behavior of a catalyst surface can be profoundly different under these contrasting environments [12].

2. Why can't techniques like LEED and HREELS be used at high pressures? Techniques such as Low-Energy Electron Diffraction (LEED) and High-Resolution Electron Energy Loss Spectroscopy (HREELS) rely on the detection of electrons that have a very short mean free path in gas phases. At pressures above UHV, these electrons undergo intense scattering by gas molecules, preventing them from reaching the detector and making the techniques non-functional [12].

3. What are the main limitations of traditional XPS under UHV? Conventional X-ray Photoelectron Spectroscopy (XPS) is limited to UHV to protect the detector and prevent electron scattering. This creates a pressure gap, as the chemical state of a catalyst surface observed in UHV may not reflect its true active state under realistic reaction conditions. Key surface intermediates might only be stable at higher pressures [13] [14].

4. How is the "material gap" different from the "pressure gap"? While the pressure gap concerns the difference in reaction environments, the material gap refers to the difference between the simple, well-defined model catalysts (like single crystals) used in fundamental studies and the complex, often nanostructured materials (like nanoparticles on oxide supports) used in industrial catalysis [15] [12].

5. What technical solutions have been developed to bridge these gaps? To bridge the pressure gap, techniques like Ambient Pressure XPS (APXPS) have been developed. These systems use specialized electron energy analyzers with differential pumping and small apertures to maintain the detector in UHV while the sample is exposed to gases at pressures up to the millibar range [13] [14]. For the material gap, researchers create supported model catalysts, such as growing well-defined metal nanoparticles on thin, ordered oxide films, which are more representative of real catalysts yet still compatible with surface science tools [15].

Troubleshooting Common Experimental Challenges

| Challenge | Root Cause | Solution & Experimental Protocol |

|---|---|---|

| Inability to observe relevant surface species during catalysis. | UHV conditions quench reactive intermediates or prevent the formation of high-pressure phases. | Protocol: Utilize Near-Ambient Pressure XPS (NAP-XPS). 1. Transfer a pre-cleaned sample to the APXPS reaction cell. 2. Introduce reactant gases (e.g., CO and O₂) to reach millibar pressures. 3. Use a synchrotron light source for high photon flux to overcome signal attenuation from gas scattering. 4. Acquire XP spectra in situ to identify active surface phases, such as high-density oxygen species on Pd during CO oxidation [14]. |

| Charging effects on insulating catalyst supports. | Electron emission from the sample during XPS measurement causes a positive charge buildup on insulating materials, shifting the measured binding energies. | Protocol: Employ thin, well-ordered oxide films as supports for metal nanoparticles. These films, grown on conductive substrates (e.g., alumina on NiAl(110)), are thin enough to allow charge stabilization, enabling the study of supported catalysts without severe charging artifacts [15]. |

| Lack of vibrational information under reaction conditions. | HREELS is a UHV technique and cannot provide data at high pressures. | Protocol: Combine APXPS with photon-based techniques. For example, simultaneously use Polarization Modulation Infrared Reflection Absorption Spectroscopy (PM-IRRAS). As photons are less scattered by gases, PM-IRRAS can provide complementary vibrational information on surface species under the same operando conditions [13]. |

| Uncertainty in correlating surface structure with reactivity. | Single crystal surfaces lack the complexity (e.g., particle size effects, metal-support interfaces) of real catalysts. | Protocol: Create a supported model catalyst and use a molecular beam for precise kinetic studies. 1. Deposit a controlled amount of metal (e.g., Pd) onto an ordered alumina film to create nanoparticles. 2. Use a molecular beam to direct a modulated flux of reactants onto the surface. 3. Monitor reaction products with a mass spectrometer to determine sticking coefficients and reaction probabilities, linking structure to function [15]. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

| Item | Function in Experiment |

|---|---|

| Ordered Oxide Thin Films (e.g., Al₂O₃/NiAl(110)) | Serves as a conductive, well-defined model support for metal nanoparticles, bridging the material gap while remaining compatible with electron-based spectroscopies [15]. |

| Differentially Pumped Electron Analyzer | The core component of APXPS systems. It uses multiple pumping stages to maintain UHV around the detector while allowing the sample region to be at higher pressures, thus bridging the pressure gap [13] [14]. |

| Electrochemical (EC) Cell with Potentiostat | Enables operando APXPS studies of electrochemical interfaces, such as those in batteries or electrocatalysis, by controlling and measuring electrochemical potentials while probing surface chemistry [13]. |

| Molecular Beam Reactor | Provides precise control over the flux, energy, and composition of reactants impinging on a model catalyst surface, allowing for detailed studies of adsorption and reaction kinetics [15]. |

| Synchrotron Radiation Source | Provides the high photon flux and brilliance necessary for APXPS to compensate for signal loss due to electron scattering in gas environments, and enables high time-resolution for tracking transient phenomena [13]. |

Technical Setup for Bridging the Pressure Gap

The diagram below illustrates a typical experimental setup for an Ambient Pressure XPS (APXPS) measurement, which allows for the study of surfaces under realistic reaction conditions.

This setup overcomes the pressure gap by physically separating the sample environment from the sensitive electron detector. The reaction cell can be filled with gases at millibar pressures, while a system of differential pumping stages, connected by small apertures, ensures that the electron analyzer remains in UHV. This allows photoelectrons emitted from the sample to be detected and analyzed under realistic catalytic conditions [13] [14].

The Impact of Adsorbate-Adsorbate Interactions at Elevated Pressures

This technical support guide addresses the critical experimental and computational challenges researchers face when studying adsorbate-adsorbate interactions at elevated pressures. In catalysis research, the "pressure gap" refers to the significant challenge of extrapolating findings from ultra-high vacuum (UHV) surface science studies to industrially relevant pressure conditions [7]. Under UHV conditions, typical of many surface science techniques, adsorbate-adsorbate interactions are often negligible. However, as pressure increases, these interactions become increasingly significant, leading to dramatic changes in surface coverage, reaction mechanisms, and catalytic selectivity [7]. This guide provides troubleshooting protocols and methodological frameworks to help researchers bridge this gap, enabling more accurate prediction of catalytic behavior under realistic operating conditions.

Frequently Asked Questions & Troubleshooting

Q1: Our experimental reaction rates at elevated pressures diverge significantly from predictions based on UHV studies. What might be causing this?

Potential Cause: The discrepancy likely stems from neglecting cooperative adsorbate-adsorbate interactions that become significant at higher coverage conditions. Under UHV, adsorbate coverage is typically low, and adsorbate-adsorbate interactions are minimal. At elevated pressures, increased coverage enhances these interactions, which can alter adsorption energies, reaction barriers, and surface diffusion rates [7] [16].

Troubleshooting Steps:

- Characterize Surface Coverage: Use techniques like in situ XPS or ambient pressure FTIR to quantify actual surface coverage under reaction conditions.

- Compute Coverage-Dependent Energetics: Employ density functional theory (DFT) calculations with increasing adsorbate coverage to model how interaction energies evolve.

- Validate with Model Systems: Compare results from single-crystal studies at low and high pressures to isolate pressure effects from material complexity effects [7].

Q2: During high-pressure adsorption experiments, we observe unexpected changes in reaction selectivity. How can we investigate the role of adsorbate-adsorbate interactions?

Potential Cause: Elevated coverages can lead to the formation of new adsorbate structures or phases that alter the available reaction pathways. Strong repulsive or attractive interactions between co-adsorbed species can block specific active sites or create new ensemble sites [16].

Troubleshooting Steps:

- In Situ Spectroscopy: Utilize in situ Raman or IR spectroscopy to identify the formation of new surface species or bonding configurations under high-pressure conditions.

- Microkinetic Modeling: Develop microkinetic models that incorporate coverage-dependent parameters derived from calculations or experiments.

- Single-Crystal Calibration: Verify if the reaction is structure-sensitive by testing on different single-crystal facets; pressure effects are more predictable for structure-insensitive reactions [7].

Q3: What computational strategies can bridge the gap between UHV models and high-pressure reality?

Core Challenge: Standard computational models often simulate isolated adsorbates on perfect crystal surfaces at 0 K, failing to capture the complex interactions at operational temperatures and pressures [7].

Methodological Solutions:

- Ab Initio Thermodynamics: Use this approach to model the equilibrium surface phase diagram as a function of temperature and pressure, identifying stable surface structures and compositions under different conditions.

- Reaction-Diffusion Models: Implement continuous models that account for local adsorbate concentration, diffusion, and lateral interactions to simulate pattern formation and growth dynamics [16].

- Accuracy Verification: Consistently validate computational predictions against experimental data obtained at comparable pressures to ensure model accuracy, as incorrect models can sometimes produce seemingly correct answers [7].

Quantitative Data on Interaction Effects

The following table summarizes key parameters and their evolution from low-pressure (UHV) to high-pressure conditions, which are critical for modeling and experimental design.

Table 1: Key Parameter Evolution from UHV to High-Pressure Conditions

| Parameter | Low-Pressure (UHV) Regime | High-Pressure Regime | Impact on Catalytic Properties |

|---|---|---|---|

| Surface Coverage (θ) | Low (often << 1 ML) | High (can approach 1 ML) | Alters active site availability, can lead to island formation or new patterning [7] [16]. |

| Adsorbate-Adsorbate Interaction Strength | Negligible | Significant (attractive or repulsive) | Modifies adsorption energies and activation barriers, directly impacting kinetics [16]. |

| Dominant Reaction Mechanism | Often simple, linear pathways | Complex, can involve coupled reactions | Changes product distribution and selectivity. |

| Surface Morphology | Stable, often the clean surface | Can reconstruct or form new adsorbate phases | Creates or blocks specific catalytic sites. |

| Reaction Order in Reactants | Can be near first-order | Often shifts to zero-order as sites saturate | Critical for reactor design and scale-up. |

Experimental Protocols for High-Pressure Studies

Protocol 1: Using High-Pressure Adsorption Instruments

High-pressure physical adsorption instruments are essential for obtaining accurate adsorption data under realistic conditions [17] [18].

- Principle: These instruments operate primarily on the static volumetric method. They measure the amount of gas adsorbed by an adsorbent material at a series of precisely controlled pressures and temperatures [18].

- Procedure:

- Sample Preparation: The solid catalyst sample is typically pre-treated (e.g., degassed) in a sample cell to remove any contaminants.

- Gas Introduction: A known amount of adsorbate gas is introduced into the system containing the sample.

- Equilibration: The system is allowed to reach equilibrium at a specific pressure (P) and temperature (T).

- Quantity Measurement: The amount of gas adsorbed is calculated by measuring the pressure change in a calibrated volume using equations of state (e.g., Peng-Robinson) [18].

- Isotherm Generation: Steps 2-4 are repeated across a wide pressure range (e.g., from vacuum up to 200 bar) to generate a complete adsorption isotherm [18].

- Troubleshooting Tip: Ensure the instrument's temperature control is highly accurate, as small temperature fluctuations can lead to significant errors in high-pressure gas uptake calculations.

Protocol 2: Computational Modeling of Interactions

The workflow below outlines a multi-scale approach to model adsorbate interactions, bridging from the atomic scale to the mesoscale.

Diagram 1: Multi-scale computational modeling workflow for adsorbate interactions.

- Key Methodological Details:

- DFT Calculations: Perform calculations with progressively larger surface unit cells and increasing adsorbate coverage to quantify the evolution of adsorption energies and identify stable adsorption sites and configurations [19].

- Ab Initio Thermodynamics: Use the outputs from DFT (adsorption energies, vibrational frequencies) to calculate the surface free energy and construct a surface phase diagram, predicting the most stable surface structures under specific pressure and temperature conditions [7].

- Reaction-Diffusion Modeling: Implement continuous models, as discussed in [16], to simulate the spatio-temporal evolution of adsorbate concentration. These models integrate terms for adsorption (Ra), desorption (Rd), and surface diffusion (J) to predict the formation of islands and other mesoscale patterns that emerge from adsorbate-adsorbate and adsorbate-substrate interactions.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Materials

Table 2: Key Materials and Computational Tools for High-Pressure Adsorbate Studies

| Item / Reagent | Function / Role | Specific Application Example |

|---|---|---|

| Single-Crystal Surfaces | Well-defined model catalysts to deconvolute pressure effects from materials effects. | Used in foundational studies, e.g., on Au single crystals, to establish baseline kinetics that can be extrapolated to higher pressures on nanoporous analogs [7]. |

| Nanoporous Model Catalysts | Bridge the materials gap, offering high surface area while maintaining relatively well-defined structures. | E.g., Nanoporous Ag₀.₀₃Au₀.₉₇ allows for comparison with single-crystal studies under industrially relevant pressures [7]. |

| High-Purity Gases (H₂, CO₂, CH₄, etc.) | Adsorbate molecules for probing surface interactions and catalytic activity. | Used in high-pressure adsorption instruments to generate accurate adsorption isotherms and study reaction kinetics [18]. |

| Density Functional Theory (DFT) | First-principles computational method for calculating electronic structure and adsorption energetics. | Used to compute adsorption energies, reaction barriers, and electronic properties (e.g., density of states, charge transfer) of adsorbate-substrate complexes [19] [16]. |

| Reaction-Diffusion Modeling Software | Tools for mesoscale simulation of surface processes, including pattern formation. | Models dynamics of adsorbate island formation and growth during deposition/adsorption processes, incorporating lateral interactions [16]. |

| In Situ Spectroscopy Cells | Reactors that allow for spectroscopic characterization of the catalyst surface under operational conditions. | Enables direct observation of adsorbates and surface intermediates during high-pressure reactions via techniques like AP-XPS or IR. |

Single-crystal models have become indispensable tools in catalysis research, offering researchers the ability to study surface reactions at the atomic level under idealized conditions. These models have driven significant advances in our fundamental understanding of catalytic mechanisms. However, a persistent challenge—known as the "pressure gap"—limits their direct applicability to industrial processes. This gap refers to the discrepancy between the ultra-high vacuum (UHV) conditions typically required for single-crystal surface analysis and the high-pressure, high-temperature environments of industrial catalysis [20].

This technical support document examines how single-crystal models both succeed and fail to predict real-world catalytic behavior. We provide troubleshooting guidance and experimental protocols to help researchers bridge the pressure gap and translate theoretical predictions into practical catalytic systems.

Understanding the Core Challenge: The Pressure Gap

FAQ: What exactly is the "pressure gap" in catalysis research?

The pressure gap describes a significant experimental limitation in catalysis science. Most surface analysis techniques require high vacuum conditions to function properly, as gas molecules would otherwise interfere with electron beams or other probe signals. However, industrial catalytic processes typically operate at atmospheric pressure or higher. This creates a fundamental disconnect: we can study model catalysts under conditions where we can characterize them, but these conditions don't reflect how catalysts actually perform in real applications [20].

FAQ: Why does the pressure gap matter for predicting catalytic performance?

Catalyst surfaces can undergo significant structural and chemical changes depending on their environment. A surface structure observed in UHV may reconstruct entirely at atmospheric pressure, potentially creating or eliminating the active sites responsible for catalytic activity. Without observing these changes in real-time under realistic conditions, predictions based on low-pressure studies may be fundamentally misleading [20].

Troubleshooting Guide: Common Experimental Challenges

Problem: Inconsistent results between model and real catalyst systems

Potential Causes and Solutions:

| Cause | Diagnostic Approach | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Surface reconstruction | Compare surface-sensitive measurements (e.g., XPS, LEED) before and after pressure changes | Implement in situ characterization techniques that operate at realistic pressures [20] |

| Missing adsorbates | Use temperature-programmed desorption (TPD) to identify weakly-bound species | Incorporate co-adsorbates present in industrial reaction environments |

| Pressure-dependent active sites | Perform activity tests across a pressure gradient | Use pressure-capable reactors with inline analytics |

Problem: Computational predictions don't match experimental observations

Potential Causes and Solutions:

| Cause | Diagnostic Approach | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Inadequate treatment of long-range interactions | Compare different computational methods (DFT vs. high-level ab initio) | Implement many-body dispersion corrections or higher-level theory [21] |

| Neglected entropy contributions | Calculate vibrational entropy contributions at operating temperatures | Include finite-temperature free energy corrections in computational models [21] |

| Simplified reaction pathways | Search for alternative reaction coordinates | Employ automated reaction pathway exploration algorithms |

Quantitative Analysis: Success Rates and Error Margins

Recent advances in computational methods have improved the accuracy of crystal form stability predictions. The table below summarizes performance metrics for modern free-energy calculation methods:

Table 1: Accuracy of Computational Crystal Form Predictions

| Calculation Method | Standard Error | Applicable Systems | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| TRHu(ST) composite method [21] | 1-2 kJ mol⁻¹ for industrially relevant compounds | Hydrates, anhydrates, multi-component systems | Requires empirical correction for water chemical potential |

| PBE0 + MBD + Fvib [21] | 2-4 kJ mol⁻¹ | Diverse molecular crystals | Computationally intensive for large systems |

| Conventional DFT | 5-10 kJ mol⁻¹ | Simple bulk crystals | Poor treatment of dispersion forces |

These error margins have significant practical implications. For context, a free-energy error of 1.7 kJ mol⁻¹ can lead to approximately a two-fold inaccuracy in predicting phase-transition relative humidity values [21].

Experimental Protocols: Bridging the Pressure Gap

Protocol: Atmospheric-Pressure XPS Using Graphene Membranes

This innovative approach enables surface characterization under realistic catalytic conditions:

Materials and Equipment:

- Bilayer graphene on silicon nitride membrane

- Modified XPS instrument with separated vacuum chambers

- High-pressure reaction cell

- X-ray source and electron detector

Procedure:

- Sample Preparation: Transfer catalyst nanoparticles to the graphene membrane surface

- Reaction Conditions: Introduce reactant gases at atmospheric pressure to the sample side

- X-ray Irradiation: Direct X-rays through the graphene membrane onto the catalyst surface

- Electron Detection: Measure ejected electrons through the vacuum-protected detector side

- Data Collection: Acquire XPS spectra while catalytic reactions proceed

- Analysis: Correlate surface composition with reaction conditions

This method has been successfully demonstrated for oxidation/reduction reactions on iridium and copper nanoparticles, and for hydrogenation of propyne on Pd black catalyst [20].

Visualization: Graphene Membrane XPS Setup

The diagram above illustrates the graphene membrane approach that enables XPS measurements at atmospheric pressure, effectively bridging the pressure gap in catalysis research [20].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 2: Key Materials for Advanced Catalysis Research

| Material/Reagent | Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Bilayer graphene [20] | Electron-transparent membrane | Enables in situ XPS at atmospheric pressure; must be defect-free |

| Iridium nanoparticles [20] | Model oxidation catalyst | Used in pressure-gap validation studies |

| Palladium black [20] | Hydrogenation catalyst | Demonstrates structure sensitivity in propyne hydrogenation |

| Metal-organic frameworks [22] | Porous catalyst supports | High surface area; tunable functionality |

| Single-crystal metal surfaces | Model catalyst substrates | Provide well-defined surface structures for fundamental studies |

Advanced Modeling Approaches: Beyond Conventional Methods

Protocol: CrysToGraph for Crystal Property Prediction

The CrysToGraph model represents a significant advancement in predicting crystal properties by addressing the challenge of capturing long-range interactions:

Model Architecture:

- Graph Construction: Atoms as nodes, k-nearest neighbors (k=12) as edges

- Line Graphs: Explicit modeling of three-body interactions

- Edge-engaged Transformer Graph Convolution (eTGC): Updates node and edge features using shared attention scores

- Graph-wise Transformer (GwT): Captures long-range dependencies across the entire crystal structure

Implementation Steps:

- Data Preparation: Convert crystal structures to graphs with 12 nearest neighbors per atom

- Feature Encoding: Use CGCNN-style atom embeddings (92 dimensions)

- Edge Feature Calculation: Compute spherical coordinates and apply radial-based filters

- Model Training: Optimize using combined short-range and long-range interaction blocks

This approach has demonstrated state-of-the-art performance on 10 out of 15 benchmark datasets for crystal property prediction [22].

Visualization: CrysToGraph Model Architecture

The CrysToGraph architecture simultaneously captures both short-range chemical interactions and long-range crystalline order, addressing a critical limitation in conventional GNNs for materials prediction [22].

Single-crystal models continue to provide invaluable fundamental insights into catalytic mechanisms but must be complemented by emerging techniques that bridge the pressure gap. The integration of in situ characterization methods like graphene-membrane XPS with advanced computational approaches such as CrysToGraph represents a promising path forward. By understanding both the capabilities and limitations of single-crystal models, researchers can develop more effective strategies for predicting and optimizing catalytic performance in real-world conditions.

As these technologies mature, the catalysis research community moves closer to the ultimate goal: predicting catalyst behavior across the full spectrum of industrial operating conditions from fundamental principles and model systems.

In-Situ and Operando Techniques: Bridging the Gap with Advanced Instrumentation

Ambient Pressure X-ray Photoelectron Spectroscopy (APXPS) has emerged as a pivotal analytical technique for investigating surface and interface chemistry under realistic conditions, directly addressing the longstanding "pressure gap" in catalysis research [23]. Conventional XPS is restricted to ultrahigh vacuum (UHV) environments, creating a significant disconnect between surface characterization and actual operational conditions where catalytic reactions occur at pressures ranging from millibar to several bar [24]. This pressure gap has historically limited our understanding of catalytic mechanisms, as catalyst surfaces can undergo dramatic reconstructions, phase changes, and adsorbate coverage variations when transitioning from UHV to realistic reaction environments.

APXPS overcomes this limitation by employing specialized differential pumping systems and electron energy analyzers capable of operating at pressures up to several tens of millibar [23]. This technological advancement enables researchers to probe elemental composition, chemical states, and potential distributions at solid/gas, solid/liquid, solid/solid, and liquid/vapor interfaces under in situ and operando conditions [25]. The ability to maintain realistic pressure environments while collecting photoelectron spectra has transformed surface science by allowing direct observation of reaction intermediates, active site identification, and dynamic surface transformations during ongoing chemical processes.

The scientific impact of APXPS extends across multiple domains including heterogeneous catalysis, electrochemistry, energy storage, corrosion science, and environmental science [26] [23]. By bridging the pressure gap, APXPS provides unprecedented insights into interfacial processes in catalysts, batteries, fuel cells, and other functional materials, enabling rational design of improved materials for energy and environmental applications.

Table: Evolution of XPS Techniques Bridging the Pressure Gap

| Technique | Operating Pressure Range | Key Applications | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Conventional XPS | <10⁻⁹ mbar | Surface composition, chemical states | Limited to UHV, excludes realistic operating conditions |

| Near-Ambient Pressure XPS (NAP-XPS) | 1-50 mbar | Catalysis, gas-solid interfaces | Limited to gas-phase applications |

| Ambient Pressure XPS (APXPS) | Up to 100 mbar | Solid/gas, solid/liquid interfaces | Signal attenuation at higher pressures |

| High-Pressure XPS (HP-XPS) | >100 mbar | Extreme condition catalysis | Requires synchrotron radiation for sufficient signal |

Technical Principles and Instrumentation

Fundamental Physics of APXPS

The core principle of APXPS relies on the photoelectric effect, where incident X-rays eject core-level electrons from sample surfaces. The kinetic energy of these photoelectrons is analyzed to determine elemental composition, chemical states, and electronic structure. In APXPS, the major technical challenge involves maintaining a higher pressure environment near the sample while effectively transmitting photoelectrons to the detector operating in high vacuum. This is achieved through multiple stages of differential pumping apertures that create a pressure gradient, reducing the pressure by several orders of magnitude between the sample chamber and the electron detector [23].

The inelastic mean free path of photoelectrons in gaseous environments fundamentally limits the maximum working pressure in APXPS. As pressure increases, electron scattering by gas molecules attenuates the photoelectron signal, particularly for lower kinetic energy electrons. This phenomenon follows an exponential decay relationship: I = I₀exp(-σPL), where I is the detected intensity, I₀ is the emitted intensity, σ is the scattering cross-section, P is the pressure, and L is the path length. Modern APXPS systems mitigate this limitation through close sample-to-aperture positioning and efficient electron collection optics [25].

Synchrotron vs. Laboratory-Based APXPS

APXPS systems can be implemented at both synchrotron facilities and laboratory environments, each with distinct advantages:

Synchrotron-Based APXPS leverages the high brilliance, energy tunability, and polarization control of synchrotron radiation [23]. Facilities like MAX IV Laboratory, Advanced Light Source (ALS), and Taiwan Photon Source (TPS) offer state-of-the-art APXPS beamlines capable of probing complex interfaces with high energy resolution, spatial resolution, and time resolution [23] [27] [25]. The high photon flux at synchrotron sources enables operando studies with milliseconds to seconds time resolution, particularly in the soft X-ray regime [23]. These facilities provide specialized environments for researching single-atom catalysts, confined catalysis, time-resolved catalysis, atomic layer deposition, and electrochemical interfaces [23].

Laboratory-Based APXPS systems utilize conventional X-ray sources (typically Al Kα or Mg Kα) and have become increasingly sophisticated, enabling routine experiments at pressures up to 20-30 mbar [24]. These systems offer greater accessibility for industrial and academic researchers, allowing for long-term studies and method development. Recent advancements in laboratory systems have demonstrated capabilities for studying catalytic reactions, electrochemical interfaces, and material transformations under near-realistic conditions [24].

Table: Representative APXPS Facilities Worldwide

| Facility | Beamline/System | Energy Range | Specialized Capabilities |

|---|---|---|---|

| MAX IV Laboratory | SPECIES, HIPPIE | Soft to tender X-rays | High time-resolution, single-atom catalysis, confined catalysis [23] |

| Advanced Light Source (ALS) | 9.3.2, 11.0.2.1 | 90-2000 eV | Solid/gas, liquid/vapor interfaces, RIXS combination [25] |

| Taiwan Photon Source (TPS) | TPS 43A, 47A | VUV to hard X-rays | APXPS, HAXPES, time-resolved PES [27] |

| Brookhaven National Laboratory | NSLS-II | Not specified | Catalysis, energy storage, materials science [26] |

| Laboratory Systems | NAP-XPS | Al Kα (1486.6 eV) | Routine catalyst characterization, method development [24] |

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Sample Preparation and Mounting

Proper sample preparation is critical for successful APXPS experiments. Catalyst powders are typically pressed into uniform pellets or deposited as thin films on conductive substrates. For model catalyst systems, well-defined nanoparticles or single crystals are used. The sample mounting approach must ensure good thermal and electrical contact while allowing precise positioning relative to the X-ray beam and analyzer entrance. For operando catalysis studies, samples are often mounted on specialized holders that incorporate heating capabilities (up to 600-800°C) and temperature monitoring [24].

Electrical grounding or charge compensation is particularly important for insulating samples, as charge accumulation can distort spectral features. In APXPS, the surrounding gas environment can provide some natural charge compensation, but additional electron flood guns or metallic meshes are often employed for optimal results. The sample position is optimized using manipulators that provide multiple degrees of freedom (x, y, z, tilt, rotation) to align the surface precisely with the "sweet spot" where the X-ray beam and analyzer axis intersect [25].

Pressure and Environmental Control

Establishing and maintaining the desired gas environment requires careful pressure and composition control. Most APXPS systems employ precision leak valves or mass flow controllers to introduce gases into the analysis chamber. The composition can be monitored using residual gas analyzers or quadrupole mass spectrometers. For reaction studies, the gas environment may be continuously flowed or static, depending on the experimental requirements [24].

Liquid-phase APXPS presents additional challenges, typically requiring the creation of liquid jets or thin films. The APPEXS endstation at ALS Beamline 11.0.2.1, for example, specializes in investigating liquid/vapor and solid/liquid interfaces using a combination of APXPS and scattering techniques [25]. For electrochemical interfaces, specialized cells with working, counter, and reference electrodes enable potential control while maintaining the required pressure conditions [23].

Data Collection and Analysis Protocols

Data collection in APXPS involves acquiring high-quality spectra with sufficient signal-to-noise ratio while maintaining experimental conditions. Typical parameters include step sizes of 0.05-0.1 eV, dwell times of 50-500 ms per step, and total acquisition times of several minutes per spectrum. For time-resolved studies, acquisition parameters are optimized to capture dynamics while maintaining adequate spectral quality [24].

Spectral analysis involves peak fitting using appropriate software, with careful consideration of background subtraction, peak shapes (typically Voigt profiles), and spin-orbit splitting. Quantification requires sensitivity factors that account for cross-sections, analyzer transmission, and mean free paths. For operando studies, spectral changes are correlated with simultaneous measurements of gas composition (via mass spectrometry) or catalytic activity (via product analysis) [24].

Diagram 1: APXPS Experimental Workflow showing the sequential steps from sample preparation to data interpretation.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs) - Technical Troubleshooting

Q1: Why do I observe significant signal attenuation in my APXPS experiments even at moderate pressures (1-10 mbar)?

Signal attenuation in APXPS primarily results from inelastic scattering of photoelectrons by gas molecules. The degree of attenuation depends on the photoelectron kinetic energy, gas composition, and path length. Lower kinetic energy electrons experience greater scattering cross-sections. To mitigate this issue: (1) Position the sample as close as possible to the analyzer entrance aperture to minimize the electron path length through the gas; (2) Utilize higher kinetic energy photoelectrons by selecting appropriate core levels or using higher energy X-ray sources (e.g., tender X-rays); (3) For synchrotron experiments, tune the photon energy to optimize the photoelectron kinetic energy; (4) Increase acquisition times or use higher flux sources to compensate for signal loss [23] [25].

Q2: How can I distinguish between surface and bulk contributions in APXPS spectra?

The surface sensitivity of XPS depends on the photoelectron kinetic energy due to the relationship between kinetic energy and inelastic mean free path. To discriminate between surface and bulk contributions: (1) Utilize the tender X-ray capabilities available at beamlines like ALS 9.3.1 (2100-6000 eV) to probe deeper into the bulk; (2) Take advantage of synchrotron radiation's energy tunability to vary the probing depth; (3) For laboratory systems, compare spectra acquired at different take-off angles (though this is more challenging in high-pressure environments); (4) Model the depth distribution of species using angle-resolved measurements or energy-dependent studies [27] [25].

Q3: What are the best practices for charge compensation in APXPS of insulating samples?

Charge compensation in APXPS can be less challenging than in conventional XPS due to the presence of ions in the gas environment. However, for reliable results: (1) Utilize the surrounding gas itself for natural charge stabilization; (2) Employ low-energy electron flood guns specifically designed for APXPS environments; (3) Use a thin metallic mesh placed slightly above the sample surface; (4) For powder samples, mix with conducting materials like graphite when possible; (5) Always reference spectra to a known internal standard, such as adventitious carbon (C 1s at 284.8 eV) or a substrate peak if available [24].

Q4: How can I confirm that my APXPS measurements reflect catalytically relevant surface states rather than artifacts?

Validating the catalytic relevance of APXPS observations requires careful experimental design: (1) Implement simultaneous mass spectrometry to correlate surface composition with gas-phase activity and selectivity; (2) Perform post-reaction characterization (e.g., TEM, XRD) to confirm structural stability, as demonstrated in the Ru nanoparticle study where TEM verified no sintering occurred during reaction; (3) Compare APXPS results with theoretical calculations to validate observed chemical states; (4) Conduct control experiments with inert or poisoned catalysts to distinguish active sites from spectators; (5) Ensure the measured reaction rates under APXPS conditions align with those in conventional reactor tests [24].

Q5: What are the current limitations in achieving higher pressures in APXPS, and what developments are underway?

The fundamental limitation for high-pressure operation is photoelectron scattering, which follows an exponential decay with increasing pressure and path length. Current research focuses on: (1) Developing novel electron optics with even shorter sample-to-aperture distances; (2) Implementing more efficient differential pumping systems; (3) Utilizing high-transmission electron energy analyzers; (4) Applying tender and hard X-rays to generate higher kinetic energy photoelectrons less susceptible to scattering; (5) Developing windowless approaches for liquid jet studies. The continued advancement of synchrotron sources like MAX IV provides brighter photons that enable measurements at higher pressures with better signal-to-noise ratios [23] [25].

Research Reagent Solutions and Essential Materials

Table: Key Research Reagents and Materials for APXPS Experiments

| Material/Reagent | Function/Application | Specific Examples from Literature |

|---|---|---|

| Model Catalyst Systems | Well-defined surfaces for fundamental studies | Ru nanoparticles (3.3 nm) on Al₂O₃ for CO₂ hydrogenation [24] |

| Support Materials | High-surface-area substrates for dispersing active phases | Al₂O₃, SiO₂, CeO₂, TiO₂ supports for metal nanoparticles [24] |

| Reference Materials | Energy calibration and method validation | Au foil (Au 4f at 84.0 eV), Cu foil (Cu 2p₃/₂ at 932.7 eV) |

| Reaction Gases | Creating realistic catalytic environments | CO₂, H₂, O₂, CO, H₂O vapor for operando catalysis studies [24] |

| Electrochemical Components | Solid/liquid interface studies | Electrolytes (aque/organic), working electrodes (Pt, Au, carbon), reference electrodes [23] |

| Calibration Compounds | Peak assignment and lineshape analysis | Standard metal foils, metal oxides with well-characterized spectra |

Case Study: Resolving the Pressure Gap in CO₂ Hydrogenation Catalysis

A recent landmark study exemplifies how APXPS directly addresses the pressure gap in catalysis research. Investigating Ru-based catalysts for CO₂ methanation (Sabatier reaction), researchers employed laboratory-based NAP-XPS to unravel the dynamic surface chemistry under realistic reaction conditions [24]. This work demonstrates the power of APXPS in bridging the pressure gap and provides a template for troubleshooting common experimental challenges.

Experimental Methodology

The research team utilized size-controlled Ru nanoparticles (3.3 nm) prepared by dc magnetron sputtering with quadrupole mass filtration to ensure uniformity [24]. The model catalysts were deposited on Al₂O₃ supports with precisely controlled coverage (9.2%). The NAP-XPS experiments were conducted under various environments: UHV, O₂, CO₂, and reactive CO₂+H₂ mixtures, with temperatures ranging from 100°C to 350°C to simulate reaction conditions [24]. A critical innovation involved developing a peak fitting model with three components (Ru⁰, RuOₓ, and RuO₂) to accurately deconvolute the complex chemical states present under operating conditions.

Key Findings and Technical Solutions

The study revealed that the fresh catalyst surface was predominantly composed of metastable RuOₓ (78%), which stabilized at the Ru-Al₂O₃ interface [24]. Under UHV conditions, complete reduction to metallic Ru⁰ required heating to 200°C, while in pure CO₂ atmosphere, oxidation persisted up to 300°C. Most significantly, in the presence of H₂ (CO₂+4H₂ mixture), reduction occurred at just 100°C, highlighting the crucial role of hydrogen in removing surface oxygen species [24]. This dramatic pressure-dependent behavior would be entirely missed in conventional UHV-XPS.

The researchers also identified distinct carbon species evolution pathways. Under reaction conditions (350°C, CO₂+H₂), the Ru catalyst accumulated C-C/C-H intermediates (>60% of carbon species), confirming its catalytic activity [24]. In contrast, pure CO₂ environment led to graphitic C=C species that poison active sites. These findings directly explain the critical role of H₂ in maintaining catalyst stability and activity, providing essential design principles for improved CO₂ methanation catalysts.

Troubleshooting Insights from the Case Study

This case study offers several important troubleshooting insights: (1) The use of size-selected nanoparticles minimizes heterogeneity, simplifying spectral interpretation; (2) The development of multi-component fitting models is essential for accurately representing complex surface chemistry; (3) Post-reaction characterization (TEM in this case) confirmed nanoparticle stability (3.3-3.7 nm after reaction), validating that observed spectral changes reflect genuine surface chemistry rather than structural degradation [24]; (4) Systematic variation of gas composition and temperature enables decoupling of individual factor effects on surface state.

Diagram 2: Bridging the Pressure Gap concept showing how APXPS enables observations missing in traditional UHV-XPS.

Advanced Applications and Future Directions

APXPS continues to evolve with technological advancements pushing the boundaries of temporal resolution, spatial resolution, and environmental complexity. At the MAX IV Laboratory, world's first fourth-generation synchrotron, the high brilliance enables time-resolved APXPS with milliseconds resolution, capturing transient reaction intermediates previously inaccessible [23]. The combination of APXPS with complementary techniques like RIXS (resonant inelastic X-ray scattering) at beamlines such as ALS 11.0.2.1 provides additional electronic structure information beyond traditional chemical state analysis [25].

Future developments focus on several frontiers: (1) High spatial resolution APXPS using nanofocused beams to chemically map heterogeneous surfaces with <50 nm resolution; (2) Ultrafast time-resolved studies capturing surface dynamics on sub-second timescales; (3) Complex environment capabilities including supercritical fluids, ionic liquids, and biologically relevant conditions; (4) Tender and hard X-ray APXPS for probing buried interfaces and complete devices; (5) Integrated multi-technique environments combining APXPS with XRD, XAFS, and optical spectroscopy for comprehensive characterization [23] [27].

The ongoing development of laboratory-based APXPS instruments promises to make this powerful technique more accessible to broader research communities. As these systems become more sophisticated, they will enable long-term studies, method development, and industrial research that complements the capabilities of synchrotron facilities. The 12th APXPS Workshop scheduled for 2025 at Brookhaven National Laboratory will showcase the latest scientific discoveries and technical innovations in this rapidly advancing field [26].

Troubleshooting Guide: Common Experimental Challenges and Solutions

Table: APXPS Troubleshooting Guide for Common Experimental Issues

| Problem | Possible Causes | Solutions | Preventive Measures |

|---|---|---|---|

| Poor Signal-to-Noise Ratio | High pressure causing electron scattering, sample degradation, insufficient photon flux | Reduce pressure temporarily for alignment, optimize sample position, increase acquisition time | Use higher flux sources, prepare stable samples, minimize path length |

| Energy Shift or Peak Broadening | Sample charging, unstable conditions, radiation damage | Use charge compensation, verify ground connection, check for sample stability | Implement proper grounding, use lower flux if possible, monitor sample condition |

| Irreproducible Results Between Experiments | Sample history effects, surface contamination, slight positional variations | Establish standardized pretreatment protocols, implement precise positioning | Document sample history thoroughly, develop reproducible mounting procedures |

| Unexpected Surface Species | Contamination from handling, residual gases, reactions during transfer | Improve transfer procedures, implement in situ cleaning, verify initial surface state | Use glove boxes for preparation, implement load-lock systems, characterize pre-and post-reaction |

| Pressure Instability | Leaks, insufficient pumping, gas condensation | Check seals and fittings, verify pump performance, avoid condensable gases | Regular maintenance, monitor pressure gauges, use gas lines with appropriate heating |

This technical support guide provides a foundation for researchers addressing the pressure gap in catalysis using APXPS. As the field continues to advance with new instrumentation and methodologies, the capabilities for probing interfaces under realistic conditions will expand, further closing the gap between idealized surface science and practical operating environments.

FAQs: Troubleshooting Your Graphene Membrane XPS Experiment

Q1: My photoelectron signal is too weak. What could be the cause?

A weak signal is often due to excessive scattering of photoelectrons. The most common causes are:

- Membrane Thickness: The graphene membrane is too thick. The detectable photoelectron signal decreases significantly with membrane thickness; for instance, only about 5% of photoelectrons pass through a membrane of 3λ thickness without being inelastically scattered [28]. Ensure you are using a single- or bi-layer graphene membrane to maximize signal [29].

- Sample Position: The catalyst nanoparticles are not directly on or in immediate proximity to the graphene membrane. Photoelectrons from samples farther away must travel through more of the high-pressure environment, increasing the probability of scattering before reaching the membrane [28] [30].

- Membrane Contamination: The membrane may be contaminated with polymers or other residues from the fabrication and transfer process, which can attenuate the photoelectron signal.

Q2: My graphene membrane ruptured during an experiment. How can I prevent this?

Graphene membranes are mechanically robust but can fail if improperly handled. To prevent rupture:

- Pressure Management: Avoid sudden, large pressure changes in the reaction cell. Ensure pressure is increased and decreased gradually.

- Check for Defects: Use microscopy (e.g., SEM) to inspect the membrane over its silicon nitride grid support before the experiment. Even pinhole defects in an otherwise perfect membrane can compromise its ability to sustain the large pressure difference [29] [30].

- Support Grid Integrity: Verify that the silicon nitride support grid with micrometer-sized holes is intact and free of cracks, as this structure is critical for bearing the mechanical load [29].

Q3: I am observing unexpected shifts in the binding energy of gas-phase species. Is this normal?

Yes, this can be a normal experimental observation. Pressure-dependent changes in the apparent binding energies of gas-phase species have been documented. These shifts are often attributable to changes in the work function of the metal-coated grids that support the graphene membrane [31]. It is crucial to account for this effect when calibrating and interpreting spectra obtained at different pressures.

Q4: Can I use this method to study liquid-phase catalytic reactions?

The graphene membrane approach is primarily developed for high-pressure gas environments. While the fundamental principle of using a membrane to separate a liquid environment from the UHV of the analyzer is sound, it presents additional challenges. These include ensuring the membrane's stability and impermeability in liquid and managing the even higher density of the liquid phase, which can strongly scatter photoelectrons [28]. This application remains an area of active development.

Experimental Protocols: Key Methodologies

Protocol for Probing Catalyst Oxidation States under Atmospheric Pressure

This protocol is adapted from a foundational study that demonstrated the stability of Cu(2+) oxidation state in O2 (1 bar) and its spontaneous reduction under vacuum [31].

Objective: To monitor the oxidation state of catalyst nanoparticles (e.g., Cu) under realistic atmospheric pressure reaction conditions.

Materials:

- Bilayer graphene membrane on a silicon nitride grid [29].

- Catalyst nanoparticles (e.g., Cu) deposited directly onto the graphene membrane.

- Atmospheric Pressure XPS system with a standard laboratory X-ray source.

Procedure:

- Setup: Mount the sample (catalyst-on-graphene) in the membrane-based AP-XPS reaction cell.

- Baseline Measurement: Evacuate the reaction cell and acquire an XPS spectrum of the catalyst (e.g., Cu 2p core level) under high vacuum to establish a baseline.

- Introduce Reactant Gas: Introduce the reactant gas (e.g., O2) into the cell, gradually increasing the pressure to the desired level (e.g., 1 bar).

- Operando Measurement: Under steady-state atmospheric pressure conditions, acquire XPS spectra of the catalyst and any gas-phase species.

- Post-Reaction Analysis: Pump down the reaction cell to high vacuum and immediately acquire another set of XPS spectra to observe any pressure-induced changes.

Troubleshooting Tip: If you do not observe a signal from gas-phase species, verify the integrity of the graphene seal and ensure your electron analyzer is calibrated for the expected binding energy range.

Protocol for Detecting Gas-Phase Reaction Products

This methodology allows for the simultaneous detection of various gas-phase species, including those with low photoionization cross-sections like H2 and He [31].

Objective: To detect and identify gas-phase species present during a catalytic reaction at pressures from 10 to 1500 mbar.

Materials:

- Graphene membrane sealed reaction cell.