Electrode Interfaces in Electrochemistry: Fundamentals, Applications, and Innovations in Drug Research

This article provides a comprehensive exploration of electrochemistry at electrode interfaces, tailored for researchers and drug development professionals.

Electrode Interfaces in Electrochemistry: Fundamentals, Applications, and Innovations in Drug Research

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive exploration of electrochemistry at electrode interfaces, tailored for researchers and drug development professionals. It covers the foundational principles governing interfacial processes, details advanced methodological applications in pharmaceutical analysis and biosensing, addresses key challenges in interface optimization and stability, and validates electrochemical methods against established analytical techniques. By synthesizing recent advancements, this review highlights the critical role of electrode interfaces in enhancing drug detection, simulating metabolic pathways, and paving the way for personalized medicine through portable sensors and AI-driven data analysis.

The Foundation of Electrode Interfaces: Principles, Dynamics, and Key Challenges

Within the field of electrochemistry, the electrochemical interface is defined as the region where an electronic conductor (an electrode) meets an ionic conductor (an electrolyte), enabling the transfer of charge and matter that constitutes an electrochemical reaction [1]. This boundary is not a simple two-dimensional plane but a complex, dynamic three-dimensional region where key processes—including the redistribution of ions, electron transfer, and chemical transformations—govern the behavior of energy storage systems, sensors, and catalytic devices [2]. The fundamental event at this interface is the redox (reduction-oxidation) reaction, where one species is oxidized by losing electrons and another is reduced by gaining them [1]. A deep understanding of the structure and dynamics of this interface is therefore critical for advancing research in electrode interfaces, particularly for applications in drug development where electrochemical sensors are used for real-time analyte detection [3].

This article frames the discussion of electrochemical interfaces within the broader thesis that interfacial stability and architecture are the pivotal factors determining the performance and longevity of electrochemical devices. Recent research highlights that challenges such as electrode fracture, uncontrolled growth of passivation layers, and dendrite formation are primarily interfacial problems that impede device reliability [2]. Consequently, elucidating the composition, kinetics, and thermodynamic properties of this region is essential for rational design of next-generation electrochemical systems.

Fundamental Principles of the Electrochemical Interface

The Site of Redox Reactions

At its core, an electrochemical cell facilitates the conversion between chemical and electrical energy. This occurs via two half-reactions taking place at physically separated electrodes: oxidation at the anode and reduction at the cathode [1] [4]. For instance, in a zinc-copper galvanic cell, zinc metal at the anode is oxidized to Zn²⁺, releasing electrons that travel through an external circuit to the cathode, where Cu²⁺ ions are reduced and deposited as solid copper [1]. The flow of electrons through the external circuit is balanced by the movement of ions within the electrolyte, maintaining electroneutrality, often assisted by a salt bridge [4].

The electric double layer (EDL) is a central concept for understanding the structure of the electrochemical interface. When an electrode is immersed in an electrolyte, a structured arrangement of ions and solvent molecules forms at the surface. In traditional aqueous systems, this EDL is often described by models like Helmholtz-Perrin or Gouy-Chapman. However, in advanced electrolytes like ionic liquids, the EDL exhibits a more complex structure with potential-dependent capacitance and oscillatory charge density profiles consisting of alternating anion- and cation-enriched layers [3]. The dynamic response of this EDL to applied potentials directly impacts sensor stability and battery charging rates.

Distinguishing Faradaic and Non-Faradaic Processes

A critical distinction in interfacial electrochemistry is between Faradaic and non-Faradaic processes:

- Faradaic currents arise from genuine redox reactions where electrons transfer across the electrode-electrolyte interface, leading to permanent chemical transformation of the electroactive species (e.g., deposition/dissolution of a metal) [1]. This current directly correlates with the rate of the electrochemical reaction and is the basis for analytical detection in sensors [3].

- Non-Faradaic (capacitive) currents result from the rearrangement of ions in the EDL during charging and discharging, without any electron transfer across the interface. While this does not cause chemical change, it can be a significant source of current, especially in high-surface-area materials or viscous electrolytes where relaxation processes are slow [1] [3].

Failure to separate these current contributions can lead to misinterpretation of data, such as overestimating reaction rates or misidentifying kinetic limitations [1]. In sensing applications, non-Faradaic processes can cause baseline drift, particularly in ionic liquids where the EDL relaxation can be slow (seconds to minutes) [3].

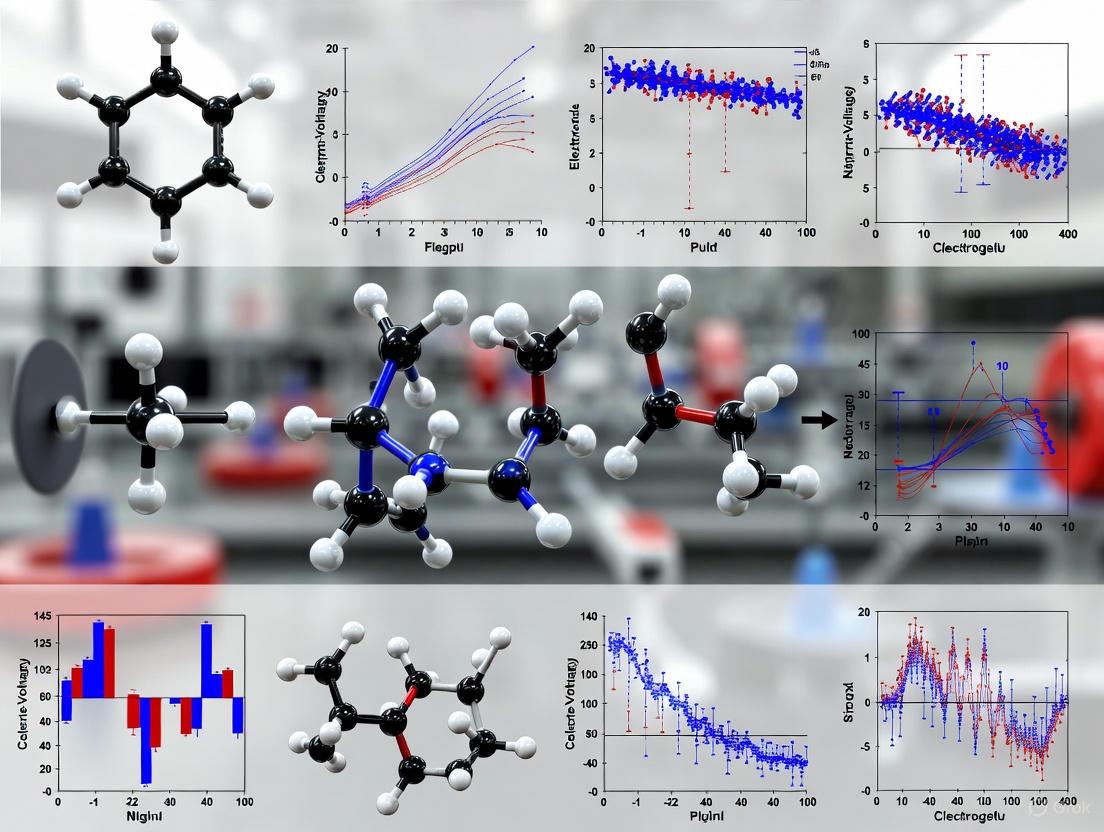

Diagram: Electrochemical Interface and Key Processes showing the fundamental components and processes at the electrochemical interface, including charge transfer pathways and the critical distinction between Faradaic and non-Faradaic processes.

Experimental Protocols for Interfacial Characterization

Protocol: Chronoamperometry for Sensor Interface Analysis

Chronoamperometry is a potential-step method valuable for studying interfacial phenomena in sensing applications, particularly for characterizing the relaxation dynamics of the electrode/ionic liquid interface [3].

Materials:

- Potentiostat/Galvanostat: For applying controlled potentials and measuring current response.

- Electrochemical Cell: Clark-type cell with working, counter, and reference electrodes.

- Working Electrode: Polycrystalline platinum gauze or microfabricated platinum black.

- Ionic Liquid Electrolyte: e.g., 1-Butyl-1-methylpyrrolidinium bis(trifluoromethylsulfonyl)-imide ([Bmpy][NTf₂]).

- Gas Permeable Membrane: Porous Teflon membrane (e.g., 5 μm pore size, 0.15 mm thickness).

- Analyte Gases: Nitrogen and 5% oxygen/nitrogen mixture.

Procedure:

- Cell Assembly: Assemble the Clark-type electrochemical cell with stacked electrode configuration. Infuse cellulose filter paper with the ionic liquid to provide electrolytic contact between electrodes [3].

- Electrode Conditioning: Condition the working electrode at zero volts instead of open circuit potential (OCP) to minimize baseline drift and enhance signal stability [3].

- Potential Step Program: Program the potentiostat to apply a series of potential steps from OCP to the amperometric sensing potential. Use multiple frequencies with different time periods (e.g., varying ON-OFF ratios) [3].

- Data Collection: Record the total current response, which is the sum of faradaic current (if) and capacitive charging current (ic), according to the equation: i(t) = if + ic [3].

- Signal Processing: Sample the current at a time exceeding five times the time constant (τ = RsCd) to ensure the capacitive charging current has decayed sufficiently, allowing quantitative analysis of the faradaic current [3].

- Interface Relaxation Assessment: Analyze the baseline recovery during the OFF period (at OCP) to determine the time required for the interface to relax to its initial state. Shorter sensing periods with extended idle periods promote more complete relaxation [3].

Data Interpretation: The faradaic current follows the Cottrell equation (if(t) = nFAD¹/²Cπ⁻¹/²t⁻¹/²), while the capacitive charging current decays exponentially (ic(t) = E/Rs × e^(-t/RsC_d)). A slow relaxation process indicates strong reorganization of the interfacial structure, which can lead to sensor baseline drift. The high viscosity of ionic liquids contributes to this slow relaxation but can be leveraged for electrochemical regeneration during conditioning steps [3].

Protocol: Electrochemical Impedance Spectroscopy for Interface Analysis

EIS is a powerful non-destructive technique for probing the charge transfer resistance, double-layer capacitance, and mass transport properties at electrochemical interfaces [2] [5].

Materials:

- Frequency Response Analyzer: Often integrated with modern potentiostats.

- Three-Electrode Cell: With well-defined reference electrode.

- Electrolyte: With supporting electrolyte to minimize solution resistance.

Procedure:

- Cell Setup: Configure the electrochemical cell with working, reference, and counter electrodes immersed in the electrolyte of interest.

- DC Bias Application: Apply a DC bias potential at the formal potential of the redox couple or at the open circuit potential.

- AC Perturbation: Superimpose a small amplitude AC signal (typically 5-10 mV) across a wide frequency range (e.g., 0.1 Hz to 100 kHz).

- Data Acquisition: Measure the magnitude and phase shift of the current response relative to the applied voltage at each frequency.

- Equivalent Circuit Modeling: Fit the resulting Nyquist and Bode plots to an appropriate equivalent circuit model representing the physical processes at the interface.

Data Interpretation: The high-frequency intercept with the real axis provides the solution resistance (Rs). The semicircle diameter in the Nyquist plot corresponds to the charge transfer resistance (Rct). The low-frequency region reflects mass transport limitations. For ionic liquid interfaces, EIS can reveal slow pseudocapacitive processes at frequencies below 10 Hz, indicating complex EDL dynamics with hysteresis effects in potential-dependent capacitance [3].

Advanced Characterization Techniques

Significant progress in understanding electrochemical interfaces has come from advanced characterization methods that probe interfacial structure and dynamics in operando. The following table summarizes key techniques and their specific applications in interfacial analysis.

Table: Advanced Characterization Techniques for Electrochemical Interfaces

| Technique | Key Application | Spatial/Temporal Resolution | Key Insights |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cryo-electron Microscopy (Cryo-EM) [2] | Atomic-level composition of solid-electrolyte interphases | Atomic resolution | Composition and spatial arrangement of SEI components |

| Time-of-Flight Secondary Ion Mass Spectrometry (TOF-SIMS) [2] | Chemical composition and morphology of interfacial layers | Depth profiling capability | Chemical mapping of SEI through sputtering control |

| Solid-State NMR (ss-NMR) [2] [5] | Chemical environments and ionic diffusion dynamics | Atomic-level chemical information | Ionic transport mechanisms and reaction intermediates |

| Spectroscopic Ellipsometry (SE) [2] | Space charge layer characterization at solid-state interfaces | Thin-film sensitivity | Physical properties of space charge layers |

| Electrochemical Quartz Crystal Microbalance (QCM-D) [1] | Coupled mass and charge transfer at interfaces | Nanogram mass sensitivity | Viscoelastic properties during interfacial processes |

| X-ray Reflectivity [3] | EDL structure in ionic liquids | Sub-nanometer resolution | Oscillatory ion layering at electrode interfaces |

These techniques have revealed that interfaces in electrochemical systems are highly complex, with structures ranging from crystalline to amorphous states, often containing reactive components sensitive to impurities, air, and electron irradiation [2]. The development of cross-scale and multimodal in situ characterization methods is crucial for real-time observation of the dynamic evolution of electrochemical interfaces [2].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table: Essential Materials for Electrochemical Interface Research

| Reagent/Material | Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Ionic Liquids (e.g., [Bmpy][NTf₂]) [3] | Low-vapor-pressure electrolyte for stable interfaces | High viscosity (61.14 cP) slows interfacial relaxation; useful for gas sensors |

| Supporting Electrolyte (e.g., KNO₃) [6] | Maintains high ionic strength; minimizes migration | Enables concentration studies without ohmic drop artifacts |

| Platinum Electrodes [3] [4] | Inert electron transfer surface | Ideal for Fe³⁺/Fe²⁺ studies where Fe electrode would participate in competing reactions |

| Porous Teflon Membrane [3] | Gas permeable barrier for Clark-type cells | 5 μm pore size, 0.15 mm thickness optimal for gas sensor applications |

| Redox Mediators [7] | Enhance charge transfer at interfaces | Species like hydroquinone/I₂ or Fe³⁺/Fe²⁺ improve supercapacitor performance |

| Solid-State Electrolytes (e.g., LLZO, LATP) [2] | Enable all-solid-state battery interfaces | Understanding reactivity with current collectors is critical for stable interfaces |

Diagram: Research Toolkit Selection showing the relationship between research objectives and appropriate characterization techniques or materials in electrochemical interface studies.

The electrochemical interface represents the crucial frontier where charge transfer and chemical transformation converge. Defining its structure and dynamics—through the integrated application of electrochemical techniques, advanced characterization methods, and tailored materials—provides the foundation for optimizing electrochemical devices. The ongoing development of in situ and in operando analytical approaches is essential for building a predictive understanding of interfacial phenomena, ultimately enabling the design of more efficient sensors, energy storage systems, and catalytic platforms. For drug development professionals, mastering these interfacial principles is particularly valuable for creating robust electrochemical sensors capable of real-time monitoring in complex biological environments.

In electrochemistry, the interface between an electrode and an electrolyte is the central locus of activity, where charge transfer reactions occur. As famously noted, "The interface is the device" [2]. Quantifying the flow of current, the driving forces of potential, and the accumulation of charge at this interface is fundamental to understanding reaction mechanisms, kinetics, and efficiency in systems ranging from energy storage devices to biosensors. This application note details the core principles, methodologies, and protocols for accurately measuring these essential parameters within the context of modern electrochemical research on electrode interfaces.

The interrelated parameters of current, voltage, and charge form the basis for characterizing electrochemical interfaces. The table below summarizes their definitions, primary measurement tools, and significance in interface research.

Table 1: Core Parameters in Electrochemical Interface Analysis

| Parameter | Definition & Units | Primary Measurement Instrument | Key Significance in Interface Research |

|---|---|---|---|

| Current (I) | Rate of electron flow due to faradaic reactions at the electrode interface. Measured in Amperes (A). | Potentiostat | Direct indicator of the rate of electrochemical reactions; used to study interface kinetics and mass transport. |

| Voltage (E) | Potential difference between the working and reference electrodes, representing the thermodynamic driving force. Measured in Volts (V). | Potentiostat / Voltmeter | Controls and probes the energy of electrons at the interface; crucial for investigating interfacial energetics and stability. |

| Charge (Q) | Integral of current over time, representing the total number of electrons transferred. Measured in Coulombs (C). | Potentiostat (via integrator) / Coulometer | Quantifies the total extent of reaction; used to determine capacity, layer formation (e.g., SEI), and adsorption processes. |

Experimental Protocols for Key Techniques

This section provides detailed methodologies for foundational experiments that probe the properties of electrochemical interfaces by manipulating and measuring current and voltage.

Protocol: Cyclic Voltammetry (CV) for Interfacial Reactivity

1. Objective: To characterize the redox activity, reaction kinetics, and stability of species at the electrode-electrolyte interface.

2. Research Reagent Solutions & Essential Materials: Table 2: Key Materials for Electrochemical Experiments

| Item | Function / Explanation |

|---|---|

| Potentiostat | The primary instrument for applying controlled potentials and measuring the resulting current. |

| Electrochemical Cell | A container (e.g., 3-neck jar) that houses the electrodes and electrolyte, providing a controlled environment. |

| Working Electrode | The electrode of interest where the interfacial reaction occurs (e.g., glassy carbon, gold, modified electrodes). |

| Reference Electrode | Provides a stable, known reference potential for the working electrode (e.g., Ag/AgCl, Saturated Calomel Electrode). |

| Counter Electrode | Completes the electrical circuit, often made of inert materials like platinum wire or mesh. |

| Electrolyte Solution | A high-conductivity solution containing sufficient supporting electrolyte to minimize solution resistance. |

| Purified Analyte | The redox-active species of interest, purified to prevent interference from side reactions. |

| Ultra-pure Water / Solvent | Used to prepare electrolyte solutions and clean glassware to prevent contamination. |

3. Procedure: 1. Cell Assembly: Clean all glassware meticulously. Insert the working, reference, and counter electrodes into the electrochemical cell. Fill the cell with the electrolyte solution containing the supporting electrolyte but not the analyte. 2. Initial Purging: Purge the electrolyte solution with an inert gas (e.g., N₂ or Ar) for at least 15-20 minutes to remove dissolved oxygen, a common electroactive interferent. 3. System Connection: Connect the electrodes to the potentiostat according to the manufacturer's instructions, ensuring correct cable connections. 4. Background Measurement: Run a cyclic voltammogram of the supporting electrolyte alone over the desired potential window. This serves as a background to identify the "potential window of the electrolyte" and confirms the absence of significant impurities. Save this scan. 5. Analyte Introduction: Add a precise quantity of the purified analyte to the cell and mix thoroughly. Continue purging with inert gas. 6. Parameter Setup: On the potentiostat software, configure the CV method: * Initial Potential: Set to a value where no faradaic reaction occurs. * High Potential Vertex: The anodic switching potential. * Low Potential Vertex: The cathodic switching potential. * Scan Rate: Define the rate of potential change (e.g., 50-100 mV/s for initial characterization). * Number of Cycles: Typically 3-5 cycles to assess reproducibility and stability. 7. Data Acquisition: Initiate the experiment. Monitor the current response in real-time to ensure the signal is within the instrument's compliance range. 8. Data Processing: Subtract the background current from the measured data. Plot current (I) vs. applied potential (E). Analyze peak currents, peak potentials, and the peak separation to extract information about the reversibility and kinetics of the interfacial reaction.

Protocol: Chronoamperometry (CA) for Interfacial Diffusion and Nucleation

1. Objective: To study the transient current associated with diffusion-limited processes, electrocatalytic reactions, or nucleation and growth phenomena at the electrode interface.

2. Procedure: 1. Steps 1-5: Follow the cell preparation and setup as described in the CV protocol (sections 3.1.1 to 3.1.5). 2. Parameter Setup: On the potentiostat, select the chronoamperometry (or current-time) technique. * Initial Potential: Set to a value where no reaction occurs. * Step Potential(s): Define the potential to which the system will be stepped. This is often to a value where the reaction is diffusion-controlled. * Pulse Width / Duration: Set the total time for which the potential step is applied. This must be long enough to observe the decay transient. 3. Data Acquisition: Initiate the experiment. The instrument will apply the potential step and record the current as a function of time. 4. Data Analysis: Plot the current response (I) versus time (t). For a simple diffusion-controlled process to a planar electrode, the current will decay according to the Cottrell equation (I ∝ t^(-1/2)). Deviations from this behavior can indicate phenomena like coupled homogeneous reactions, adsorption, or multi-step electron transfers.

Protocol: Electrochemical Impedance Spectroscopy (EIS) for Interfacial Properties

1. Objective: To deconvolute the resistive and capacitive properties of the electrochemical interface and investigate charge transfer kinetics.

2. Procedure: 1. Cell Setup: Prepare the electrochemical cell as in previous protocols. The system should be at a steady-state, often at the open-circuit potential (OCP) before measurement. 2. Parameter Setup: * DC Bias Potential: The potential at which the interface is probed (often OCP or a specific applied potential). * AC Amplitude: A small sinusoidal perturbation, typically 5-10 mV, to ensure a linear system response. * Frequency Range: A broad range, usually from 100 kHz (or 1 MHz) down to 100 mHz (or 10 mHz). 3. Data Acquisition: Run the EIS experiment. The potentiostat applies the AC potential and measures the magnitude and phase shift of the resulting current across the frequency spectrum. 4. Data Analysis: Plot the data as a Nyquist plot (Imaginary vs. Real impedance) and a Bode plot. Use equivalent circuit modeling to fit the data and extract quantitative parameters such as the solution resistance (Rs), charge transfer resistance (Rct), and double-layer capacitance (C_dl), which is directly related to the electroactive surface area and state of the interface [2].

Experimental Workflow and Data Interpretation

The following diagram illustrates the logical workflow for planning, executing, and analyzing experiments focused on the electrochemical interface.

Advanced Interface Characterization and Future Outlook

Understanding electrochemical interfaces requires moving beyond basic measurements. Advanced architectural analysis often employs a suite of complementary techniques [2]. For instance, incremental capacity analysis (ICA) and differential voltage analysis (DVA) can help quantify contributions from different electrode and interfacial processes. Furthermore, the growth, rupture, and repair of interphases like the solid-electrolyte interphase (SEI) are primary mechanisms governing the lifetime of devices like batteries, and their study requires evaluating parameters such as solvent, salt, and electrolyte concentration [2].

The future of interfacial electrochemistry lies in the development and application of in situ and operando characterization methods. Techniques like in situ spectroscopic ellipsometry (SE) can characterize space charge layers within solid-state electrolytes [2], while cryo-electron microscopy (cryo-EM) offers the potential to resolve SEI composition at the atomic level [2]. Correlating data from these advanced methods with the foundational electrical measurements of current, voltage, and charge is crucial for building a comprehensive, multiscale understanding of the dynamic processes at electrochemical interfaces.

Interfacial phenomena are fundamental to the performance and reliability of advanced electrochemical systems, including energy storage devices and drug delivery platforms. The processes that occur at the interfaces between different materials often dictate the overall efficiency, stability, and functionality of these systems. This article examines three critical interfacial phenomena—wettability, ion transfer, and space charge layers—through the lens of practical application and experimental investigation. Within the context of a broader thesis on electrochemistry at electrode interfaces, we present standardized protocols and analytical frameworks to quantify and optimize these phenomena, supported by recent research advancements. The insights provided are particularly relevant for researchers and scientists working toward the development of next-generation batteries and targeted pharmaceutical systems, where interfacial control is paramount.

Wettability in Electrochemical Systems

Quantitative Analysis of Electrode Wettability

Table 1: Wettability Parameters and Performance Metrics in Electrochemical Systems

| Material/System | Contact Angle (°) | Test Method | Impact on Performance | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| NZZSPO Solid Electrolyte (untreated) | 63.1 | Sessile drop | Poor interfacial contact, high resistance | [8] |

| NZZSPO Solid Electrolyte (EAP-treated) | 10.5 | Electrowetting | Superior interfacial contact, low resistance | [8] |

| Calendered Li-ion Electrode (Optimal) | Not specified | Washburn method | Improved energy density, reduced porosity | [9] |

| Over-Calendered Li-ion Electrode | Not specified | Washburn method | Decreased wettability, smaller pore diameter | [9] |

Wettability, quantified by parameters such as contact angle, fundamentally governs the interfacial contact and electrolyte penetration in porous electrodes and solid-state battery configurations. Insufficient electrolyte wetting leads to irregular reactions, unstable solid-electrolyte interface (SEI) formation, and underutilization of electrode capacity, which ultimately deteriorates cell performance and cycle life [9]. In solid-state sodium metal batteries, poor wettability contributes to dendrite formation and catastrophic failure, necessitating sophisticated interfacial engineering strategies [8].

The electrowetting interfacial coating effect presents a promising approach to overcome these challenges. According to the Young-Lippmann equation, an applied electric field can optimize the contact angle of liquid droplets on solid electrolytes [8]:

$$\cos {\theta }{{ew}}=\cos {\theta }{Y}+\frac{{c}{H}{\left(V-{V}{{pzc}}\right)}^{2}}{{2\gamma }_{{\mathrm{lg}}}}$$

where θ_ew is the electrowetting contact angle, θ_Y is the intrinsic contact angle without an applied field, V is the applied voltage, V_pzc is the zero charge potential, c_H is the electrical double layer capacitance per unit area, and γ_lg is the interfacial tension. This principle enables the creation of superhydrophilic surfaces with contact angles as low as 10.5°, significantly improving interfacial contact compared to conventional methods (63.1°) [8].

Experimental Protocol: Electrode Wettability Enhancement via Electrowetting

Purpose: To achieve complete interfacial coating and healing in solid-state batteries through electroinitiated accelerated polymerization (EAP).

Materials:

- Ethyl 2-cyanoacrylate (ECA) monomers as interfacial mending glue (IMG)

- Solid-state electrolyte (e.g., NZZSPO) pellets

- Sodium metal electrodes

- High-voltage power supply for electrospray

- Sealed optical cell for in-situ monitoring

- FT-IR and Raman spectrometers

Procedure:

- Interface Preparation: Clean the solid-state electrolyte (NZZSPO) and sodium metal electrode surfaces to remove contaminants.

- Electrospray Setup: Position the electrode and electrolyte assembly with approximately 100μm separation. Connect to a high-voltage power supply.

- Charged Microdroplet Generation: Apply a high electric field (specific voltage dependent on setup geometry) to generate charged IMG microdroplets via electrospray. The net charge enhances thermodynamic reactivity.

- Electrowetting Coating: Allow charged microdroplets to deposit on the electrolyte surface. The reduced interfacial tension causes nearly complete spreading (contact angle ~10.5°).

- Preferential Defect Filling: Monitor the filling of inherent cracks, voids, and surface roughness features via in-situ microscopy.

- Polymerization Initiation: Facilitate electron transfer from the electrode to electrophilic ECA monomers, generating carbanions that initiate anionic polymerization.

- Interface Characterization: Confirm complete polymerization via FT-IR spectroscopy (disappearance of C=C stretch at 1633 cm⁻¹ and =CH₂ bends at 3130 cm⁻¹) [8].

Validation: The EAP strategy increases the polymerization rate by 21.4 times compared to conventional methods, enabling rapid interface healing and achieving a critical current density of 6.8 mA cm⁻² in solid-state sodium metal batteries [8].

Quantifying Interfacial Ion Transfer

Advanced Measurement Techniques

Table 2: Techniques for Quantifying Interfacial Ion Transfer

| Technique | Spatial Resolution | Key Measurable Parameters | Applicable Systems | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Scanning Electrochemical Microscopy (SECM) | Micrometer-scale | Local ion concentration, Effective insertion rates | Aqueous and non-aqueous batteries | Requires compatible redox mediator |

| Finite Element Modeling (FEM) | Numerically determined | Ion concentration gradients, Transport kinetics | Simulated electrode interfaces | Dependent on model parameters |

| Voltammetry at Microelectrodes | Millisecond temporal | E1/2 shift vs. ion concentration | High concentration electrolytes (up to 3 mol dm⁻³) | Sensitivity to mediator stability |

Interfacial ion transfer is a fundamental process in insertion-type battery electrodes, directly impacting power performance. Quantifying these phenomena at operating concentrations remains challenging. Scanning electrochemical microscopy (SECM) with a ferri/ferrocyanide (FeCN) redox mediator enables tracking of local alkali ion concentration changes during insertion and deinsertion processes, even at high electrolyte concentrations up to 3 mol dm⁻³ [10].

The SECM method capitalizes on the reversible shift in half-wave potential (E₁/₂) of approximately 60 mV per decade change in K⁺ concentration. This stable response enables precise positioning of a platinum microelectrode at the surface of a potassium-insertion electrode to monitor local concentration changes during operation. When combined with 2D axisymmetric finite element modeling, this approach provides estimates of effective insertion rates, offering a key parameter for improving battery performance [10].

Experimental Protocol: Interfacial Ion Transfer Kinetics via SECM

Purpose: To quantify interfacial ion transfer kinetics at operating battery electrodes using scanning electrochemical microscopy.

Materials:

- Scanning electrochemical microscope with potentiostat

- Platinum microelectrode (tip diameter: 1-25μm)

- Ferri/ferrocyanide (FeCN) redox mediator

- Potassium-insertion electrode material

- Aqueous electrolytes with varying K⁺ concentrations (0.1-3 mol dm⁻³)

- Reference and counter electrodes

- Finite element modeling software (COMSOL or equivalent)

Procedure:

- System Calibration:

- Prepare standard K⁺ solutions with known concentrations (0.1, 0.5, 1, 2, 3 mol dm⁻³) containing 5 mM FeCN.

- Perform cyclic voltammetry at the Pt microelectrode for each standard solution.

- Plot E₁/₂ values against log[K⁺] to establish calibration curve (expected shift: ~60 mV per decade).

Electrode Preparation:

- Fabricate potassium-insertion electrode using standard slurry casting methods.

- Assemble electrochemical cell with the insertion electrode as working electrode.

SECM Measurement:

- Position the Pt microelectrode within 1-2 electrode diameters from the insertion electrode surface.

- Fill cell with electrolyte containing FeCN mediator at operating concentration.

- Initiate potassium insertion/deinsertion via galvanostatic or potentiostatic control.

- Simultaneously monitor E₁/₂ shifts at the microelectrode during cycling.

Data Analysis:

- Convert recorded E₁/₂ values to local K⁺ concentrations using calibration curve.

- Map temporal and spatial concentration profiles near the electrode interface.

- Implement 2D axisymmetric finite element model to fit concentration data.

- Extract effective insertion rate constants from model optimization.

Validation: The method demonstrates high stability in sequential measurements and enables direct correlation between interfacial ion concentration and electrode operation, providing insights into mass transport limitations at practical battery concentrations [10].

Space Charge Layers in All-Solid-State Batteries

Revisiting Space-Charge Layer Theories

Table 3: Space-Charge Layer Properties in Solid Electrolytes

| Solid Electrolyte | Electrode Material | Presumed SCL Properties | Actual SCL Properties | Impact on Resistance |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Li₀.₃₃La₀.₅₆TiO₃ (LLTO) | Not specified | Li-deficient, ~5.5 nm width | Li-excess, ~40 nm width | Minimal (efficient transport) |

| LLZO (Li₇La₃Zr₂O₁₂) | LCO (LiCoO₂) | ~1 nm thickness | Modeled: ~1 nm thickness | Negligible resistance |

| LATP (Li₁.₂Al₀.₂Ti₁.₈(PO₄)₃) | Graphite | Complete Li⁺ depletion possible | Modeled: Nanometer scale | Potentially significant if depleted |

Space-charge layers (SCLs) at solid-solid interfaces have frequently been implicated as the cause of large interfacial resistances in all-solid-state batteries. Conventional theory suggests that positively charged grain-boundary cores in solid electrolytes like LLTO drive away nearby Li⁺ ions, creating Li-deficient SCLs that impede ion transport [11]. However, recent atomic-scale studies challenge this paradigm.

Direct observation via aberration-corrected transmission electron microscopy and electron energy loss spectroscopy reveals that grain-boundary cores in LLTO are actually negatively charged, resulting in Li-excess SCLs approximately 40 nm wide, contrary to the previously speculated 5.5 nm Li-deficient layers [11]. These Li-excess regions accommodate additional Li⁺ at the 3c interstitials and enable efficient ion transport, suggesting that the SCLs themselves are not the major bottleneck for ion transport. Instead, the Li-depleted grain-boundary cores are identified as the primary cause of large grain-boundary resistance [11].

Computational modeling supports these findings, indicating that space-charge layers in typical electrode-electrolyte combinations are approximately one nanometer thick, with negligible associated resistance for Li-ion transport—except when completely depleted Li⁺ layers form in the solid electrolyte [12]. The equilibrium state of SCLs is governed by the balance between chemical and electrical potentials, described by the relationship:

$$\frac{d\mu (x)}{dx} + ze\frac{d\phi (x)}{dx} = 0$$

where μ is the chemical potential, z is the ionic charge, e is the elementary charge, and φ is the electric potential [12].

Experimental Protocol: Atomic-Scale Characterization of Space-Charge Layers

Purpose: To directly characterize the atomic configuration and Li distribution in space-charge layers of solid electrolytes.

Materials:

- LLTO or other solid electrolyte ceramics

- Aberration-corrected transmission electron microscope (AC-TEM)

- High-angle annular dark-field (HAADF) scanning TEM system

- Electron energy loss spectroscopy (EELS) detector

- Focused ion beam (FIB) system for sample preparation

- X-ray diffractometer for phase verification

Procedure:

- Sample Preparation:

- Prepare LLTO ceramics using standard sintering methods.

- Verify phase purity via X-ray diffraction.

- Confirm ionic conductivity consistency with literature values using electrochemical impedance spectroscopy.

- Prepare electron-transparent thin sections (<100 nm) containing grain boundaries using FIB.

HAADF-STEM Imaging:

- Acquire atomic-resolution HAADF-STEM images of grain boundaries.

- Analyze contrast variations (proportional to Z¹·⁷) to identify elemental depletion/enrichment.

- Note that darker regions indicate La depletion at grain-boundary cores.

EELS Analysis:

- Acquire spectra across grain boundaries with 4 nm spatial resolution.

- Analyze Li-K edge, Ti-L₂,₃ edge, and O-K edge for chemical composition.

- Normalize Li-K intensity to La-N₄,₅ integrated intensity to account for thickness variations.

- Calculate normalized Li-K intensity as percentage of La-N₄,₅ intensity.

Data Interpretation:

- Plot normalized Li-K intensity against distance from grain-boundary core.

- Identify Li-rich regions (normalized intensity >16% vs. bulk 8.07%) extending approximately 40 nm from boundary.

- Confirm Ti/O ratio consistency in grain-boundary core indicating TiOₓ composition.

Validation: The combined approach reveals that actual SCLs are Li-excess rather than Li-deficient, with a width of ~40 nm, fundamentally changing the understanding of resistance origins in solid electrolytes [11].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 4: Key Research Reagents and Materials for Interfacial Studies

| Reagent/Material | Function/Application | Key Characteristics | Research Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ethyl 2-cyanoacrylate (ECA) monomers | Interfacial mending glue for defect healing | Polymerizes via anionic mechanism under electric field | Solid-state battery interface healing [8] |

| Ferri/ferrocyanide (FeCN) redox mediator | Tracking alkali ion concentration changes | Reversible E1/2 shift of ~60 mV per decade [K⁺] | SECM studies of ion transfer [10] |

| Li₀.₃₃La₀.₅₆TiO₃ (LLTO) | Model solid electrolyte for SCL studies | Perovskite structure, large grain-boundary resistance | Atomic-scale SCL characterization [11] |

| NZZSPO Solid Electrolyte | Oxide solid electrolyte for Na batteries | Na₃.₄Zr₁.₉Zn₀.₁Si₂.₂P₀.₈O₁₂ composition | Electrowetting interface studies [8] |

| Platinum Microelectrode | SECM probe for localized measurements | 1-25μm diameter, precise positioning | Ion transfer quantification [10] |

The pursuit of higher energy density and safer electrochemical energy storage systems has brought the critical role of electrode-electrolyte interfaces into sharp focus. Within the context of advanced battery technologies, particularly lithium-metal and all-solid-state batteries, the stability of this interface governs overall cell performance, longevity, and safety. Lithium dendrite formation—the uncontrolled growth of metallic filaments during cycling—presents a fundamental challenge, as it can penetrate separators, cause internal short circuits, and lead to thermal runaway [13]. Simultaneously, interfacial degradation through parasitic side reactions consumes electrolyte and active materials, increasing resistance and causing capacity fade [14] [15]. This application note delineates the core scientific principles underlying these interface challenges and provides detailed protocols for investigating and mitigating them, framing the discussion within a broader electrochemistry research thesis.

The central hypothesis driving this field is that interfacial instability originates from complex, interdependent processes including: (i) thermodynamic driving forces that favor non-uniform lithium deposition and dissolution [16]; (ii) chemical and electrochemical reactions at the interface that form unstable or non-protective interphases [17] [18]; and (iii) mechanical failures and spatial heterogeneities in solid-state systems that locally enhance current density [13]. A multi-scale approach, combining advanced computational modeling with high-resolution in situ characterization, is essential to deconvolute these mechanisms and inform rational design strategies for stable interfaces.

Core Interface Challenges: Mechanisms and Quantitative Analysis

Lithium Dendrite Formation: Thermodynamic and Kinetic Drivers

Lithium dendrite formation remains the most critical barrier to implementing lithium metal anodes. The process is governed by an interplay of thermodynamic and kinetic factors. Thermodynamically, the nucleation and growth of lithium are highly susceptible to localized energy landscapes, which promote inhomogeneous deposition over uniform films [16]. From a kinetic perspective, the rate of lithium-ion depletion at the electrode surface often exceeds the diffusion-limited rate from the bulk electrolyte, creating a constitutional super-saturation that destabilizes the deposition front [13].

Table 1: Fundamental Drivers and Characteristics of Lithium Dendrite Formation

| Driver Category | Specific Mechanism | Key Influencing Factors | Observed Morphology |

|---|---|---|---|

| Thermodynamic | Low Li nucleation barrier [16] | Surface energy, temperature, substrate material | Isolated, mossy Li nuclei |

| Electrochemical | Localized current hotspots [13] | Interfacial contact area, SEI conductivity, grain boundaries | Filamentary, dendritic growth |

| Transport-Limited | Li+ concentration gradient [18] | Current density, Li+ transference number, electrolyte conductivity | Branching, fractal-like dendrites |

| Mechanical | Solid electrolyte fracture [13] | Stack pressure, electrolyte shear modulus, defect density | Dendrites penetrating SSE |

Recent insights from machine-learning-enhanced molecular dynamics simulations under constant potential conditions have directly visualized the initial stages of dendrite nucleation. These simulations reveal that inhomogeneous lithium deposition is often initiated by the aggregation of lithium atoms within amorphous inorganic components of the solid electrolyte interphase (SEI), creating protrusions that focus the electric field and accelerate further growth [19]. Furthermore, the charge distribution at the interface is a critical descriptor, as it dictates the reaction pathways of electrolyte components; for instance, the bond cleavage sequence of LiFSI salt changes under charged versus uncharged conditions, directly influencing the composition and passivation quality of the SEI [17].

Interfacial Degradation and Instability

Beyond dendrites, continuous interfacial degradation poses a major challenge to cycle life. In liquid electrolyte systems, this primarily involves the reductive decomposition of electrolyte components to form the SEI. While a stable SEI is essential, it often evolves during cycling, consuming active lithium and electrolyte and increasing interfacial resistance [17] [18]. In all-solid-state batteries (SSBs), the challenges are distinct and include chemical incompatibility between the solid electrolyte and electrodes, leading to the formation of resistive interlayers [15].

Table 2: Types and Consequences of Interfacial Degradation in Battery Systems

| System | Degradation Type | Primary Cause | Impact on Performance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Liquid Electrolyte | Unstable SEI growth [18] | Reduction of solvents/salts at low potential | Active Li consumption, capacity fade, increased impedance |

| Solid-State Battery | Interfacial side reactions [15] | Chemical potential difference between electrode and solid electrolyte | High interfacial resistance, poor kinetics |

| Solid-State Battery | Contact loss [13] | Volume changes of electrode during cycling | Local current density increase, dendrite initiation |

| High-Voltage System | Cathode Electrolyte Interphase (CEI) breakdown [14] | Oxidative decomposition at high voltage | Transition metal dissolution, catalytic electrolyte breakdown |

A key finding in SSBs is the critical role of the Li chemical potential ((μ{Li})) at the interface. The alignment of (μ{Li}) between the electrode and solid electrolyte during bonding can lead to Li extraction or insertion into the electrode, forming non-stoichiometric regions that are highly resistive [15]. For example, when a LiCoO₂ cathode is combined with a lithium phosphate oxide nitride (LiPON) electrolyte, differences in Fermi energy can cause electron transfer that reduces Co³⁺ and degrades the cathode structure [15]. This underscores that interfacial stability is not merely a chemical issue but also an electronic one, where controlling the Fermi energy and band alignment is crucial for forming low-resistivity interfaces.

The diagram below illustrates the interconnected mechanisms that lead to the two primary failure modes: dendrite growth and interfacial degradation.

Diagram 1: Causal pathways linking root causes to interfacial failure modes, highlighting the interplay between electrochemical, chemical, and mechanical factors.

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Protocol: Investigating SEI Formation and Stability Using Multivalent Cation Additives

Objective: To evaluate the effectiveness of multivalent cation additives (e.g., Ca²⁺, La³⁺) in modifying the solvation structure and promoting the formation of a stable, anion-derived SEI on lithium metal anodes [18].

Materials:

- Base Electrolyte: 1.0 M LiTFSI in EC:PC (1:1 v/v).

- Additives: Ca(TFSI)₂, La(TFSI)₃.

- Electrodes: Li metal chips (counter/reference), Cu foil (working electrode).

- Cell: Standard coin cell (CR2032) configuration.

Procedure:

- Electrolyte Preparation: In an argon-filled glovebox (< 0.1 ppm H₂O/O₂), prepare the control electrolyte (1.0 M LiTFSI in EC:PC). For test electrolytes, add multivalent cation salts (e.g., 0.1 M Ca(TFSI)₂ or 0.05 M La(TFSI)₃) to the base electrolyte and stir for 24 hours to ensure complete dissolution.

- Cell Assembly: Assemble coin cells using the Cu working electrode, Li counter/reference electrode, a standard separator, and 80 µL of the prepared electrolyte.

- Electrochemical Cycling: Cycle the cells using a battery cycler. Perform Li plating at a constant current density of 0.5 mA cm⁻² for 1 hour (0.5 mAh cm⁻²), followed by stripping to a cut-off voltage of 1.0 V vs. Li/Li⁺. Repeat for multiple cycles to assess stability.

- Coulombic Efficiency (CE) Calculation: Monitor the charge during plating (Qₚ) and stripping (Qₛ). Calculate CE for each cycle as (Qₛ / Qₚ) × 100%. A higher and more stable CE indicates improved reversibility.

- Post-Mortem Analysis: After cycling, disassemble cells in the glovebox. Wash the Cu electrode with pure DMC solvent to remove residual salts and gently dry it.

- XPS Analysis: Transfer the electrode via a vacuum-sealed transfer vessel to an XPS system. Analyze the SEI composition, focusing on the F 1s (for LiF content), C 1s, O 1s, and, if applicable, La 3d or Ca 2p regions. A higher F 1s signal indicates an anion-derived, more stable SEI.

- SEM Imaging: Characterize the lithium deposition morphology. A flat, dense morphology is indicative of successful dendrite suppression.

Protocol: Quantifying Interfacial Resistance in Solid-State Thin-Film Cells

Objective: To measure and understand the origin of interfacial resistance between a LiCoO₂ (LCO) cathode and a lithium phosphate-based solid electrolyte (LPO) with varying Li/P atomic ratios [15].

Materials:

- Substrates: Pt/Ti/SiO₂/Si wafers.

- Electrodes: Sputter-deposited, c-axis oriented LCO thin films.

- Solid Electrolyte: Amorphous LPO thin films deposited via bias-induced RF magnetron sputtering with controlled Li/P ratios (2 to 9).

- Top Electrode: Li metal.

Procedure:

- Thin-Film Fabrication:

- Deposit a 100 nm thick, c-axis oriented LCO film on the Pt-coated substrate using pulsed laser deposition (PLD) or sputtering.

- Deposit a 1.5-2.0 µm thick LPO film on the LCO surface using RF magnetron sputtering from a Li₃PO₄ target. To vary the Li/P ratio, apply a substrate bias (0 V to -6 V) and maintain the substrate at temperatures below -80 °C to ensure an amorphous structure.

- Surface Characterization: Use X-ray Photoelectron Spectroscopy (XPS) to determine the precise Li/P, O/P, and N/O atomic ratios on the surface of the LPO film.

- Cell Assembly: In a glovebox, evaporate a Li metal anode onto the LPO surface to complete the Li/LPO/LCO/Pt cell stack.

- Electrochemical Impedance Spectroscopy (EIS):

- Perform EIS measurements at a DC bias of 4.0 V (vs. Li/Li⁺) at 25 °C.

- Use a frequency range of 1 MHz to 0.1 Hz and a small AC amplitude (e.g., 10 mV).

- Data Analysis:

- Fit the resulting Nyquist plot with an equivalent circuit model, typically a resistor in series with a parallel (resistor-constant phase element) combination. The diameter of the semicircle corresponds to the interfacial charge-transfer resistance (Rₘₜ).

- Plot Rₘₜ against the Li/P atomic ratio. The optimal Li/P range for the lowest resistance (e.g., < 10 Ω cm²) can be identified. Excess Li (high Li/P) causes reductive degradation of LCO, while Li deficiency (low Li/P) leads to irreversible phase formation in LCO, both increasing resistance.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Key Reagents and Materials for Interface Research

| Category / Item | Example Compounds | Primary Function in Research |

|---|---|---|

| Liquid Electrolyte Salts | LiTFSI, LiPF₆, LiFSI | Conduct Li+ ions; FSI/TFSI anions promote LiF-rich SEI. |

| Multivalent Additives | Ca(TFSI)₂, La(TFSI)₃ | Modify solvation structure, promote CIPs/AGGs, enhance SEI stability [18]. |

| Solid-State Electrolytes | LiPON, LLZO, Li₆PS₅Cl | Replace flammable liquids; study interface stability & dendrite blocking in SSBs [13] [15]. |

| Polymer Matrices | PEO, PVDF-HFP | Base for flexible solid/composite electrolytes; study ion transport & interface compatibility [14]. |

| Interface Modifiers | LiF, Li₃PO₄, LiNbO₃ | Artificial SEI or coating layers to physically block dendrites and suppress side reactions [13]. |

| Flame Retardants | HNT@FPPN nanohybrids | Additives to improve safety of polymer electrolytes without sacrificing ionic conductivity [14]. |

Visualization of Experimental Workflow for Interface Engineering

The following diagram outlines a generalized, iterative research workflow for developing and characterizing stable electrode-electrolyte interfaces, integrating the protocols and strategies discussed in this note.

Diagram 2: Cyclical workflow for interface engineering R&D, from initial concept through characterization to data-driven design refinement.

Electroanalytical Methods and Their Transformative Applications in Biomedicine

Electrode interfaces are the central arena where critical electrochemical processes occur, governing the performance of energy storage systems, sensors, and catalytic devices. Understanding these interfaces requires analytical techniques that can probe interfacial reactions with high sensitivity and specificity [2]. Voltammetry, a class of electrochemical methods that measure current as a function of applied potential, provides such insights [20]. This application note details three essential voltammetric techniques—Cyclic Voltammetry (CV), Differential Pulse Voltammetry (DPV), and Square Wave Voltammetry (SWV)—framed within contemporary research on electrochemical interfaces. It provides structured protocols, comparative analysis, and practical guidance for researchers and scientists engaged in fundamental electrochemistry and applied drug development.

Cyclic Voltammetry (CV)

Cyclic Voltammetry is a powerful technique for studying the kinetics of electrochemical reactions and mechanisms. In CV, the current response is measured while the potential of the working electrode is swept linearly between two set limits (vertex potentials) at a controlled scan rate, producing a characteristic cyclic profile [20]. The resulting I vs. E plot provides information on redox potentials, reaction reversibility, and diffusion coefficients. For a simple, reversible one-electron transfer reaction, the peak current (Ip) is described by:

$$ I{\text{p}} = -0.446AzFC{\text{A}}\sqrt{zf\text{N} v{\text{b}}D{\text{A}}} ; f\text{N} = F/RT $$ [20]

where A is the electrode surface area, F is the Faraday constant, CA is the concentration of species A, vb is the scan rate, and D_A is the diffusion coefficient.

Differential Pulse Voltammetry (DPV)

DPV is a pulse technique designed to minimize non-Faradaic (charging) background current, thereby enhancing measurement sensitivity [21] [22]. In DPV, a series of small potential pulses (typically 10-100 mV) are superimposed on a linear staircase baseline. The current is sampled twice for each pulse: just before the pulse application (i1) and at the end of the pulse (i2) [21] [22]. The differential current, Δi = i2 - i1, is plotted against the base potential, yielding peak-shaped voltammograms where the peak height is proportional to analyte concentration [21]. For a reversible system, the peak current is given by:

$$ Ip = \frac{nFAD^{1/2}C}{\pi^{1/2}tp^{1/2}} \cdot \frac{P}{1+P} $$ [21]

where P = exp[(nF/RT)(ΔE/2)], ΔE is the pulse amplitude, and tp is the pulse period.

Square Wave Voltammetry (SWV)

SWV combines the advantages of pulse techniques with rapid scanning capability. A high-frequency square wave is superimposed on a staircase waveform. The current is sampled at the end of each forward (if) and reverse (ir) potential pulse, and the difference (idiff = if - ir) is plotted against the base potential [23] [24]. This differential plot amplifies the Faradaic response and effectively suppresses capacitive background currents [25]. SWV is particularly useful for studying surface-confined reactions and determining charge transfer kinetics [23] [25]. The normalized peak current can be used to determine the standard rate constant by identifying the critical frequency at which the current is maximized [25].

Comparative Analysis of Techniques

Table 1: Comparative characteristics of voltammetric techniques.

| Parameter | Cyclic Voltammetry (CV) | Differential Pulse Voltammetry (DPV) | Square Wave Voltammetry (SWV) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Primary Application | Mechanism elucidation, reaction kinetics [20] | Quantitative trace analysis [22] | Kinetic studies, surface-bound processes [23] [25] |

| Waveform | Linear potential sweep between two limits [20] | Staircase with small superimposed pulses [21] | Staircase with superimposed square wave [23] |

| Current Measurement | Continuous during sweep [20] | Difference (i₂ - i₁) per pulse [21] [22] | Difference (iforward - ireverse) [23] [24] |

| Background Suppression | Moderate | Excellent [21] | Excellent [23] [25] |

| Speed | Moderate (scan rate dependent) | Slow | Very Fast (1-125 Hz typical frequency) [23] |

| Sensitivity | Micromolar (~10⁻⁶ M) | Nanomolar to picomolar (~10⁻⁹ to 10⁻¹² M) [22] | Nanomolar (~10⁻⁹ M) [23] |

| Information Obtained | Redox potentials, reversibility, reaction mechanisms [20] | Quantitative concentration, peak potential [21] [22] | Charge transfer kinetics, surface coverage [25] |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol for Cyclic Voltammetry

Objective: To determine the reversibility and redox potential of a reversible analyte.

- Cell Assembly: Use a standard three-electrode cell: Working Electrode (e.g., glassy carbon, Pt disk), Counter Electrode (Pt wire), and Reference Electrode (Ag/AgCl, SCE) [20].

- Solution Preparation: Prepare a solution containing the analyte (e.g., 1-10 mM) in a suitable supporting electrolyte (e.g., 0.1 M KCl, phosphate buffer) [20]. Deoxygenate with inert gas (N₂ or Ar) for 10-15 minutes.

- Instrument Parameters (EC-Lab or equivalent):

- Initial Potential (Einit): 0.5 V (a potential where no reaction occurs)

- Vertex Potential 1 (E₁): 0.5 V

- Vertex Potential 2 (E₂): -0.3 V

- Scan Rate (vb): Begin with 0.1 V/s [20]

- Number of Cycles: 3-5

- Execution: Start the experiment. Monitor the resulting voltammogram for the appearance of symmetric reduction and oxidation peaks.

- Data Analysis:

- Note the peak potentials (Epc for cathodic peak, Epa for anodic peak).

- Calculate ΔEp = Epa - Epc. For a reversible, one-electron transfer, ΔEp ≈ 59 mV [20].

- Confirm that the peak current ratio (Ipa / Ipc) is close to 1.

- Vary the scan rate to study kinetics; Ip should be proportional to the square root of the scan rate (vb^(1/2)) for diffusion-controlled processes [20].

Protocol for Differential Pulse Voltammetry

Objective: Quantitative determination of lead (Pb) and cadmium (Cd) in tap water [22].

- Cell Assembly: Use a three-electrode system with a Hanging Mercury Drop Electrode (HMDE) as the working electrode, an Ag/AgCl reference electrode, and a Pt counter electrode [22]. Note: Mercury electrodes are ideal for heavy metal detection but require careful handling and disposal.

- Solution Preparation:

- Sample: 10 mL of filtered tap water.

- Supporting Electrolyte: Add 0.5 mL of acetate buffer (1 M ammonium acetate + 1 M acetic acid) [22].

- Standard Additions: Prepare known concentrations (e.g., 1 mg/L) of Pb and Cd standard solutions.

- Instrument Parameters (NOVA or AfterMath software):

- Initial Potential: -0.9 V

- Final Potential: -0.2 V

- Pulse Height (ΔE): 50 mV

- Pulse Width: 50 ms

- Step Height (ΔE_s): 2-5 mV

- Step Time: 100-500 ms [22]

- Execution & Quantification (Standard Addition Method):

- Pre-conditioning: Purge with nitrogen and form a fresh Hg drop. Apply a pre-concentration potential of -0.9 V under stirring to reduce and accumulate metal ions at the Hg electrode [22].

- Measurement: Stop stirring and run the DPV scan from -0.9 V to -0.2 V. Record the voltammogram.

- Standard Additions: Add known volumes of Pb and Cd standard solutions (e.g., 100 µL, then 200 µL) to the cell, repeating the pre-conditioning and measurement after each addition [22].

- Analysis: Measure the peak heights for Cd (~-0.58 V) and Pb (~-0.40 V). Plot peak height vs. analyte concentration for the sample and standard additions. The absolute value of the x-intercept gives the original sample concentration [22].

Protocol for Square Wave Voltammetry

Objective: Study of a surface-bound redox system, such as an electrochemical aptamer-based (E-AB) sensor [25].

- Cell Assembly: Use a three-electrode cell with a gold working electrode (2 mm diameter), a Pt counter electrode, and an Ag/AgCl reference electrode [25].

- Sensor Fabrication:

- Clean and polish the gold electrode.

- Incubate the thiol-modified aptamer probe (reduced with TCEP) on the gold electrode surface for 1 hour to form a self-assembled monolayer [25].

- Passivate the surface with 6-mercapto-1-hexanol (30 mM) to block non-specific adsorption [25].

- Equilibrate in Tris buffer.

- Instrument Parameters (CH Instruments or AfterMath):

- Initial Potential: A potential positive of the formal potential (E°) of the redox tag (e.g., Methylene Blue).

- Final Potential: A potential negative of E°.

- Amplitude: 25 mV

- Frequency (f): 10-100 Hz (Start at 60 Hz) [25]

- Increment: 1 mV

- Execution:

- Run the SWV experiment. The output is a plot of the difference current (Idiff) vs. potential.

- The result is a peak whose height is related to the surface coverage of the redox-active aptamer and whose position is related to E°.

- Data Analysis:

- To study kinetics, perform SWV at different frequencies. The normalized peak current (Ip/f) reaches a maximum at a critical frequency related to the electron transfer rate constant [25].

- A shift in this critical frequency upon target (e.g., drug) binding indicates a change in the aptamer's conformation and electron transfer kinetics [25].

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 2: Essential research reagents and materials for voltammetric experiments.

| Item | Function/Application | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| Supporting Electrolyte | Minimizes solution resistance; ensures current is carried by ions, not the analyte. | 0.1 M KCl for general use; Acetate buffer for heavy metal analysis [22]. |

| Redox Probe | Well-characterized standard for electrode calibration and method validation. | Potassium ferricyanide (K₃[Fe(CN)₆]) for CV on solid electrodes [25]. |

| Working Electrodes | Surface at which the controlled electrochemical reaction occurs. | Glassy Carbon (general use); HMDE (trace metal analysis) [22]; Gold (surface-modified sensors) [25]. |

| Reference Electrodes | Provides a stable, known potential for the working electrode. | Ag/AgCl (3 M KCl) [25] [22]; Saturated Calomel Electrode (SCE). |

| Purified Gases | Removes dissolved oxygen, which can interfere with measurements. | Nitrogen (N₂) or Argon (Ar) for deaerating solutions prior to analysis [22]. |

| Aptamer Sequences | Biorecognition elements for specific target binding in sensor development. | Functional nucleic acids (e.g., for ATP or tobramycin) for E-AB sensing [25]. |

Signaling and Workflow Diagrams

Cyclic, Differential Pulse, and Square Wave Voltammetry offer a complementary toolkit for interrogating electrochemical interfaces, each with distinct strengths. CV remains the primary technique for initial mechanistic studies, while DPV excels in ultra-sensitive quantification, and SWV provides rapid, high-information-content data on kinetics and surface processes. The ongoing development of advanced interfacial architectures for batteries and sensors [26] [2] underscores the critical role of these techniques. By selecting the appropriate method and following rigorous protocols, researchers can extract detailed information on charge transfer, degradation mechanisms, and binding events, thereby accelerating innovation in electrochemistry and drug development.

Biosensors are analytical devices that integrate a biological recognition element with a physicochemical transducer to produce a measurable signal proportional to the concentration of a target analyte. The electrochemical interface, defined as the boundary where electrode materials and electrolytes engage in energy conversion and information transfer, serves as the central hub determining biosensor performance [27] [2]. Its microscopic structure, electronic properties, and dynamic ionic behavior directly govern reaction kinetics, mass transfer efficiency, and system stability, thereby defining the sensitivity, selectivity, and detection limits of the entire biosensing device [27].

The evolution from traditional enzyme-based biosensors to advanced biomolecule-free sensors represents a significant paradigm shift in electrochemical biosensing. This transition addresses critical challenges associated with the intrinsic instability of biological recognition elements and their limited operational lifespans under varying environmental conditions [28] [29]. Enzyme-based biosensors leverage the specificity and catalytic efficiency of biological enzymes, while enzyme-free approaches utilize direct electrocatalytic oxidation at nanostructured material interfaces, offering enhanced stability and reduced complexity [30] [29]. Both approaches fundamentally rely on precisely engineered electrochemical interfaces where molecular recognition events are transduced into quantifiable electrical signals.

Enzyme-Based Biosensing Systems

Fundamental Principles and Components

Enzyme-based biosensors consist of three essential components: (1) enzymes as biological recognition elements, (2) transducers that convert biochemical reactions into measurable signals, and (3) immobilization matrices that stabilize the enzyme and maintain its proximity to the transducer [28]. The functional mechanism relies on specific enzyme-substrate interactions where catalytic reactions produce detectable byproducts such as hydrogen peroxide, oxygen, protons, heat, or light [28].

These biosensors are classified by their transduction methods, which include:

- Electrochemical: Amperometric (current measurement) and potentiometric (voltage measurement) systems detecting changes in electrical signals from enzyme-mediated redox reactions [28]

- Optical: Systems measuring changes in absorbance, fluorescence, luminescence, surface plasmon resonance, or chemiluminescence [28]

- Thermal: Thermistor-based sensors detecting heat changes during enzymatic reactions [28]

- Mass-sensitive: Piezoelectric devices measuring mass changes on sensor surfaces [28]

Key Enzymes and Their Applications

Table 1: Key Enzymes Used in Biosensor Development and Their Applications

| Enzyme | Catalytic Reaction | Primary Applications | Common Transduction Methods |

|---|---|---|---|

| Glucose Oxidase (GOx) | Oxidation of β-D-glucose to gluconic acid and H₂O₂ | Diabetes management, food industry sugar analysis | Amperometric, Potentiometric [28] |

| Urease | Hydrolysis of urea to ammonia and CO₂ | Kidney function diagnostics, environmental monitoring | Optical (chemiluminescence, SPR) [28] |

| Lactate Oxidase (LOx) | Conversion of L-lactate to pyruvate and H₂O₂ | Sports medicine, critical care metabolic monitoring | Amperometric, Wearable sensors [28] |

| Cholesterol Oxidase (ChOx) | Oxidation of cholesterol to cholest-4-en-3-one and H₂O₂ | Cardiovascular health monitoring, food science | Electrochemical, Optical [28] |

| Acetylcholinesterase (AChE) | Hydrolysis of acetylcholine to choline and acetate | Pesticide detection, neurotoxin monitoring | Electrochemical [28] |

| Tyrosinase | Oxidation of phenolic compounds to quinones | Environmental monitoring, food antioxidant detection | Amperometric, Optical [28] |

Advanced Application: E-DNA Sensor for miRNA Detection in Whole Serum

Experimental Principle: This conformational change-based electrochemical DNA (E-DNA) sensor detects miRNA through a binding-induced structural rearrangement of a redox-tagged DNA probe immobilized on a gold electrode surface [31]. In the absence of the target miRNA, the probe structure positions the methylene blue (MB) redox tag near the electrode surface, generating a strong faradaic current. Upon hybridization with the specific miRNA target, the conformational change displaces the redox tag away from the electrode, significantly reducing the electron transfer efficiency and producing a measurable signal drop [31].

Protocol: miRNA-29c Detection in Whole Human Serum

Materials and Reagents:

- Thiolated MB-tagged DNA capture probe (sequence: SH(CH₂)₆-TAACCGATTTCAAATGGTGCTA-MB) [31]

- Target miRNA-29c (sequence: UAGCACCAUUUGAAATCGGUUA) [31]

- Phosphate buffered saline (PBS, 10 mM, pH 7.4) containing 137 mM NaCl and 2.7 mM KCl [31]

- Gold working electrode, reference electrode, and counter electrode [31]

- Square-wave voltammetry (SWV) setup [31]

Experimental Procedure:

- Electrode Pretreatment: Clean the gold working electrode through electrochemical cycling in sulfuric acid solution to ensure a pristine surface [31].

- Probe Immobilization: Incubate the electrode with 100 nM thiolated DNA capture probe in PBS buffer for 2 hours at room temperature to form a self-assembled monolayer via gold-thiol bonding [31].

- Surface Blocking: Treat the electrode with 6-mercapto-1-hexanol (1 mM) for 30 minutes to passivate uncovered gold surfaces and minimize non-specific adsorption [31].

- Target Detection: Incubate the functionalized electrode with undiluted human serum samples spiked with miRNA-29c (concentration range: 0.1-100 nM) for 60 minutes at 37°C [31].

- Electrochemical Measurement: Perform square-wave voltammetry measurements from -0.1 V to -0.5 V (vs. reference electrode) with frequency 60 Hz and amplitude 25 mV [31].

- Signal Analysis: Quantify the relative current decrease compared to the baseline (no target) measurement. The signal follows a sigmoidal response curve fitting the Langmuir-Hill model [31].

Performance Characteristics:

- Detection Range: 0.1-100 nM miRNA-29c in whole serum [31]

- Selectivity: Excellent discrimination against non-complementary and two-base-mismatched sequences [31]

- Recovery Rate: ±10% in spiked serum samples [31]

- Fouling Resistance: Maintains performance in undiluted biological fluids due to conformational change mechanism [31]

Biomolecule-Free Sensing Systems

Principles of Enzyme-Free Electrochemical Sensing

Non-enzymatic electrochemical sensors represent the next generation of biosensing platforms, eliminating biological recognition elements in favor of direct electrocatalytic oxidation/reduction of target analytes at strategically designed electrode interfaces [30] [29]. These systems circumvent limitations associated with enzyme instability, temperature and pH sensitivity, and complex immobilization procedures [29]. Instead, they rely on nanomaterial-enabled catalytic activity where the electrode surface itself facilitates both recognition and signal transduction through adsorption and subsequent electrocatalytic oxidation of target molecules [29].

The fundamental mechanism involves the formation of reactive interfacial species that drive the oxidation process. In alkaline media, metal-based sensors typically generate metal hydroxide/oxyhydroxide intermediates that act as strong oxidizing agents for the target molecules [29]. For instance, cobalt-based sensors undergo surface transformations from Co₃O₄ to CoOOH and finally to CoO₂ containing Co(IV) atoms, where CoO₂ serves as the primary oxidant for glucose conversion to gluconolactone [29].

Advanced Application: Cobalt Hydroxycarbonate-Based Glucose Sensor

Experimental Principle: This enzyme-free glucose sensor utilizes nanostructured cobalt hydroxycarbonate (Co₆(CO₃)₂(OH)₈) as an electrocatalytic material for the direct oxidation of glucose [29]. The material is synthesized via a simple one-step hydrothermal method and modified with zinc dopants to enhance catalytic activity through morphology control and increased active surface area [29].

Protocol: Enzyme-Free Glucose Sensor Fabrication and Testing

Materials and Reagents:

- Cobalt(II) nitrate hexahydrate (Co(NO₃)₂·6H₂O) [29]

- Zinc nitrate hexahydrate (Zn(NO₃)₂·6H₂O) for doping [29]

- Urea (CO(NH₂)₂) as hydroxycarbonate source [29]

- Sodium hydroxide (NaOH) for alkaline measurement conditions [29]

- Glucose solutions (0-3 mM concentration range) [29]

Sensor Fabrication Procedure:

- Hydrothermal Synthesis: Prepare growth solution containing 0.1 M cobalt nitrate and 0.5 M urea in deionized water. For zinc-doped material, add 2 mol% zinc nitrate to the growth solution [29].

- Material Preparation: Transfer the solution to a Teflon-lined autoclave and maintain at 120°C for 6 hours to facilitate crystalline nanostructure formation [29].

- Product Collection: Centrifuge the resulting precipitate, wash thoroughly with ethanol and deionized water, and dry at 60°C overnight [29].

- Electrode Modification: Prepare an ink by dispersing 5 mg of the synthesized material in 1 mL ethanol with 5 μL Nafion solution. Drop-cast 10 μL of the ink onto a glassy carbon electrode and air-dry [29].

Glucose Detection Protocol:

- Electrochemical Setup: Use a standard three-electrode configuration with the modified working electrode, Ag/AgCl reference electrode, and platinum counter electrode in 0.1 M NaOH electrolyte [29].

- Amperometric Measurement: Apply a constant potential of +0.55 V (vs. Ag/AgCl) while continuously stirring the solution [29].

- Glucose Addition: Introduce successive aliquots of glucose stock solution to achieve concentration increments within the 0-3 mM range [29].

- Current Recording: Monitor the steady-state current response after each glucose addition. Plot current density versus glucose concentration to establish calibration curves [29].

Performance Characteristics:

- Sensitivity: 6745 μA cm⁻² mM⁻¹ (Zn-doped) vs. 1950 μA cm⁻² mM⁻¹ (undoped) [29]

- Linear Range: Up to 3 mM glucose [29]

- Detection Limit: 16 μM (Zn-doped) vs. 30 μM (undoped) [29]

- Stability: No significant degradation after three months of storage under normal conditions [29]

Table 2: Performance Comparison of Enzyme-Free Glucose Sensing Materials

| Material | Sensitivity (μA cm⁻² mM⁻¹) | Linear Range (mM) | Detection Limit (μM) | Stability |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cobalt Hydroxycarbonate (Zn-doped) [29] | 6745 | 0-3 | 16 | >3 months |

| Cobalt Hydroxycarbonate (undoped) [29] | 1950 | 0-3 | 30 | >3 months |

| Gold-Based Sensors [29] | Up to 700 | 0.01-20 | 1-50 | Varies |

| Porous Gold/Polyaniline/Platinum Composite [32] | 95.12 ± 2.54 (μA mM⁻¹ cm⁻²) | Not specified | Not specified | Stable in interstitial fluid |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Biosensor Development

| Reagent/Material | Function/Application | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|

| Glucose Oxidase (GOx) [28] | Biological recognition element for glucose biosensors | High specificity for β-D-glucose, produces H₂O₂ as detectable product |

| Cobalt Hydroxycarbonate (Co₆(CO₃)₂(OH)₈) [29] | Enzyme-free glucose sensing material | Nanostructured, high catalytic activity, tunable morphology |

| Gold Electrodes [31] | Transducer platform for electrochemical biosensors | Excellent conductivity, facile thiol-based functionalization |

| Thiolated DNA Probes [31] | Recognition elements for nucleic acid biosensors | Self-assembling monolayer formation, conformational change capability |

| Methylene Blue (MB) [31] | Redox tag for conformational change-based sensors | Reversible electrochemistry, distance-dependent electron transfer |

| Nafion Perfluorinated Resin [29] | Electrode binder and membrane | Chemical resistance, cation selectivity, stability in biological media |

| Polydopamine [32] | Surface modification and functionalization | Biocompatibility, universal adhesion, versatile chemistry |

| Graphene & Carbon Nanotubes [28] | Nanomaterial enhancers for sensor interfaces | High surface area, excellent conductivity, catalytic properties |

The evolution from enzyme-based to biomolecule-free biosensors represents significant progress in electrochemical interface engineering for analytical applications. Enzyme-based systems offer exceptional specificity through biological recognition but face challenges in stability and environmental sensitivity [28]. In contrast, enzyme-free approaches provide enhanced operational stability and simplicity through direct electrocatalysis at nanomaterial-functionalized interfaces [30] [29].

Future developments will likely focus on hybrid approaches that incorporate the best attributes of both systems, potentially through synthetic enzymes or biomimetic nanomaterials that combine the specificity of biological recognition with the stability of inorganic materials [28] [27]. The integration of artificial intelligence in electrochemical interface design promises to accelerate this development by enabling predictive modeling of structure-activity relationships and optimizing the trade-offs between performance, cost, and sustainability [27]. Additionally, emerging trends point toward increased miniaturization, multimodal sensing capabilities, and integration with wearable platforms for continuous health monitoring applications [32] [33].

The continued advancement of both enzyme-based and enzyme-free biosensing platforms will fundamentally rely on deeper understanding and precise engineering of the electrochemical interface—where molecular recognition events are transduced into quantifiable signals that drive diagnostic decisions and enable personalized medicine.

Electrochemistry-mass spectrometry (EC-MS) has emerged as a powerful, purely instrumental technique for simulating the oxidative phase I metabolism of drug candidates. By mimicking the electron-transfer reactions catalyzed by cytochrome P450 (CYP) enzymes, EC-MS enables rapid generation and identification of potential metabolites under controlled conditions, providing a valuable complementary approach to conventional biological methods [34] [35]. This application note details the theoretical foundations, experimental protocols, and practical applications of EC-MS within the broader context of electrochemical interface research, providing researchers and drug development professionals with a framework for implementing this technology.

The fundamental principle underlying EC-MS is the electrochemical simulation of biological redox processes at the electrode-solution interface. As electrode interfaces serve as the central platform for these electron-transfer reactions, understanding their architecture and properties is crucial for optimizing metabolic simulations [2]. The technique is particularly valuable for predicting drug metabolism pathways, identifying reactive metabolites, and generating metabolite standards without the need for extensive biological experiments [36] [37].

Technical Foundations and Applications

Principle of Operation

EC-MS functions by integrating an electrochemical flow-through cell directly with mass spectrometric detection, often with liquid chromatographic separation (EC-LC-MS). The electrochemical cell serves as an electron-transfer interface where drug molecules undergo controlled oxidation or reduction, simulating metabolic transformations that typically occur in the liver [35]. The resulting products are then characterized by mass spectrometry, providing structural information about potential metabolites.

The technique effectively mimics Phase I metabolism, particularly CYP450-catalyzed reactions, since the enzymatic catalytic cycle involves essential electron transfer steps [36]. Over 90% of pharmaceutical compounds possess redox-active properties, making them amenable to electrochemical simulation [37]. Key metabolic reactions that can be simulated include N-dealkylation, aromatic hydroxylation, S-oxidation, and dehydrogenation [38] [37].

Current Research Applications