Essential Surface Science Textbooks: A Curated Guide for Researchers and Drug Development Professionals

This guide provides a strategic selection of surface science textbooks tailored for researchers, scientists, and professionals in drug development.

Essential Surface Science Textbooks: A Curated Guide for Researchers and Drug Development Professionals

Abstract

This guide provides a strategic selection of surface science textbooks tailored for researchers, scientists, and professionals in drug development. It systematically navigates from foundational principles and modern analytical techniques to practical troubleshooting and comparative resource analysis. The article empowers readers to select the ideal textbooks for mastering surface science fundamentals, applying methodological knowledge to real-world challenges like pharmaceutical formulation and device development, and validating their analytical approaches.

Building Your Core Knowledge: Foundational Surface Science Textbooks

For researchers and scientists entering the field of surface science, a solid foundation is built upon authoritative textbooks that clearly explain both fundamental principles and advanced characterization techniques. This guide curates key texts and foundational knowledge essential for professionals in fields like drug development, where surface phenomena are critical.

Foundational Textbooks in Surface Science

The following table summarizes essential textbooks that provide comprehensive introductions to the field of surface science.

| Textbook Title & Edition | Key Focus & Scope | Target Audience & Level | Notable Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| Surface Science: An Introduction [1] | Covers all major aspects of modern surface science, from experimental background and crystallography to analytical techniques and applications in thin films and nanostructures [1]. | Advanced undergraduate and graduate students in engineering and physical sciences; researchers beginning in the field [1]. | Presents topics in a concise, accessible form with numerous figures (372), exercises, and problems; praised for its clarity and compactness [1]. |

| Modern Techniques of Surface Science, 3rd Edition [2] | A thorough introduction to characterization techniques used in surface science and nanoscience. It compares techniques for solving specific research questions [2]. | Senior undergraduate students, researchers, and practitioners performing materials analysis [2]. | Chapters organized by research question (e.g., surface composition, structure) to help readers select the most suitable techniques for their research [2]. |

| Surface Science Techniques, 1st Edition [3] | A comprehensive review of techniques to determine surface nature and composition, including electron/ion spectroscopies and atom-imaging methods like STM [3]. | University research workers, graduate students, and industrial scientists solving practical problems [3]. | A carefully edited collection of chapters written by specialists in each technique, with coverage of routinely used and more fundamental methods [3]. |

Conceptual Framework and Core Principles

Surface science is an interdisciplinary field studying phenomena at the interfaces between different phases (solid, liquid, gas, vacuum), crucial for processes like catalysis, adhesion, and corrosion [4]. The field historically developed from two converging paths: surface physics and surface chemistry [4].

- Surface Physics: Focused on fundamental questions about clean surfaces, often of single crystals in ultra-high vacuum (UHV). Key questions include surface structure, atomic layer spacing, and the concentration of defects like steps and kinks [4].

- Surface Chemistry: Inherently involved molecules from gas or liquid phases interacting with surfaces, with early applications in heterogeneous catalysis (e.g., ammonia synthesis) and colloid science [4].

The maturation of surface science has bridged these tracks, leading to applications in diverse fields including biomaterials, nanotechnology, and microelectronics [4].

Foundational Experimental Methodology

A core activity in surface science is the preparation and analysis of well-defined surfaces, a methodology that bridges the surface physics and chemistry approaches.

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

The table below lists key materials and equipment used in the preparation and analysis of model surfaces.

| Item Name | Function/Application |

|---|---|

| Single Crystal Substrate | A solid with a highly ordered, defect-free surface, used as a model system to study fundamental surface properties and processes [4]. |

| Ultra-High Vacuum (UHV) System | A chamber pumped to very low pressure (e.g., 10⁻⁹ torr) to create and maintain a clean, contamination-free surface for extended periods [4]. |

| Ion Sputtering Gun | A source of energetic ions (e.g., Ar⁺) used to remove surface contamination layers (e.g., oxides) by bombarding the surface [4]. |

| Annealing Furnace/Oven | A heat source used to re-order the surface atomic structure after sputtering, healing defects and creating a well-ordered crystalline surface [4]. |

Step-by-Step Experimental Workflow

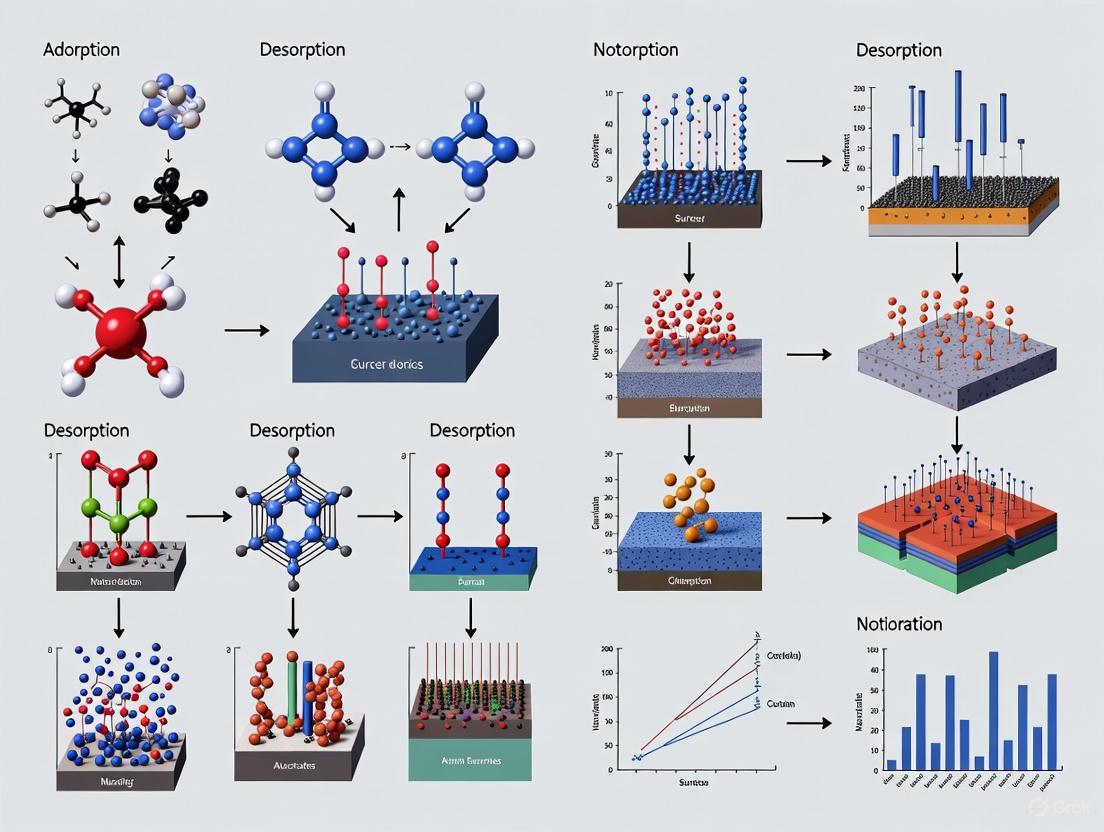

The following diagram and protocol outline a classic procedure for creating a clean, well-ordered single-crystal surface for fundamental studies.

Detailed Protocol:

- Sample Preparation: A single crystal is cut and polished to expose a specific low-index crystal plane, defining the surface orientation to be studied [4].

- UHV Introduction: The prepared crystal is mounted onto a sample holder and transferred into an ultra-high vacuum (UHV) chamber. This environment is critical to prevent immediate re-contamination of the surface by gases in the air [4].

- Ion Sputtering: The surface is bombarded with a beam of inert gas ions (e.g., Ar⁺). This process physically removes (sputters) any surface contaminants, such as oxides or carbonaceous species, leaving a clean but often structurally damaged surface [4].

- Thermal Annealing: The sputtered sample is heated to a high temperature (annealing). This provides atoms at the surface with sufficient thermal energy to migrate, re-ordering into a thermodynamically stable, well-defined crystalline structure with minimal defects [4].

- Surface Characterization: The cleanliness and structural order of the prepared surface are verified using in-situ techniques. Low-Energy Electron Diffraction (LEED) can confirm long-range order, while X-ray Photoelectron Spectroscopy (XPS) quantitatively analyzes surface elemental composition and chemical states [4]. This iterative preparation and analysis cycle is foundational for producing reliable and reproducible surface science data.

Surface science is a critical field of study that examines the physical and chemical phenomena occurring at the interface between two phases, including solid-gas, solid-liquid, and liquid-gas boundaries. The outermost surface layers of a material play a crucial role in processes such as catalysis, adhesion, wear, and corrosion, with broad applications across metallurgy, thin films and surface coatings, the chemicals and polymer industries, and microelectronics [3]. This field explores how the properties of a material's surface—which can differ dramatically from its bulk properties—govern its interactions with the environment and other materials. The understanding of these underlying principles is foundational for advancements in technology and industry, from developing more efficient catalysts to creating novel electronic devices.

The significance of surface science is further amplified in specialized fields like pharmaceutical development, where the surface characteristics of a compound can influence its bioavailability, stability, and interaction with biological targets. Systematic analysis of surface properties allows researchers to relate a compound's structure to its activity, a relationship central to rational drug design [5]. This guide provides an in-depth examination of the core principles, analytical techniques, and methodologies that define modern surface science.

Foundational Principles and Concepts

Thermodynamics of Surfaces

Surface thermodynamics addresses the energy considerations at interfaces. A fundamental concept is surface free energy or surface tension, which arises because atoms or molecules at a surface have fewer neighbors to bond with compared to those in the bulk material, resulting in an unbalanced force and higher energy state. This excess energy drives many surface processes. The thermodynamic drive to minimize this surface energy influences processes such as adsorption, where foreign atoms or molecules (adsorbates) adhere to a surface, thereby lowering its energy. Another key phenomenon is surface reconstruction, where the atoms at the surface of a crystal rearrange into a structure that is different from the bulk to achieve a more stable, lower-energy configuration.

Symmetry and Structure

The atomic structure of a surface is defined by its symmetry and periodicity. The concept of a Bravais lattice is used to describe the two-dimensional periodic arrangement of atoms on a surface. The specific arrangement of atoms, including steps, kinks, and terraces, creates distinct surface sites with different chemical reactivities and physical properties. Understanding this structure is vital, as it directly dictates how the surface will interact with adsorbates. The study of surface structure involves characterizing these arrangements and understanding how they deviate from the ideal bulk termination.

Electronic Structure of Surfaces

The electronic properties at a surface are distinctly different from those in the bulk of a material. The termination of the crystal lattice leads to the presence of dangling bonds and the formation of surface states within the electronic band gap. These electronic states can act as trapping centers for charge carriers or as active sites for chemical reactions. The electronic structure determines key properties such as work function (the minimum energy needed to remove an electron from the solid to a point in the vacuum far away outside the surface), surface conductivity, and catalytic activity. Techniques like photoelectron spectroscopy are specifically designed to probe this electronic landscape [6].

Key Analytical Techniques in Surface Science

A range of sophisticated techniques has been developed to characterize the structure, composition, and chemistry of surfaces. The table below summarizes the fundamental principles and applications of key surface analysis methods.

Table 1: Key Techniques for Surface Analysis

| Technique | Acronym | Primary Information | Typical Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| X-ray Photoelectron Spectroscopy [3] | XPS | Elemental identity, chemical state, and electronic state of elements within the top 1-10 nm. | Analysis of thin oxide layers, polymer surface chemistry, contamination studies. |

| Auger Electron Spectroscopy [3] | AES | Elemental composition (except H, He) of the top 0.5-3 nm; can be used for depth profiling. | Failure analysis, microelectronics quality control, corrosion studies. |

| Secondary Ion Mass Spectrometry [3] | SIMS | Elemental and molecular composition of the outermost 1-2 atomic layers; extremely high sensitivity for trace elements. | Dopant profiling in semiconductors, study of organic monolayers. |

| Scanning Tunneling Microscopy [3] | STM | Real-space, atomic-resolution image of the surface topography and electronic density of states. | Atomic-scale imaging of reconstruction, defect studies, manipulation of atoms. |

| Atom Probe Field Ion Microscopy [3] | APFIM | Three-dimensional, atomic-scale elemental mapping of a specimen. | Nanoscale compositional analysis in metallurgy and materials science. |

| Angle-Resolved UV Photoelectron Spectroscopy [3] | ARUPS | Electronic band structure of solids and their surfaces. | Fundamental studies of electronic properties of new materials. |

| Surface Infrared Spectroscopy [3] | - | Identification of molecular functional groups and bonding of adsorbates on surfaces. | Study of catalytic reaction mechanisms, self-assembled monolayers. |

| Ion Scattering Spectroscopy [3] | ISS | Elemental composition of the absolute outermost atomic layer. | Determination of the termination layer of a crystal surface. |

| Rutherford Backscattering [3] | RBS | Quantitative elemental composition and depth profile without standards; non-destructive. | Analysis of thin film composition and inter-diffusion. |

Experimental Protocol: Surface Analysis via X-ray Photoelectron Spectroscopy (XPS)

This protocol provides a detailed methodology for determining the elemental composition and chemical state of a solid surface using XPS, following guidelines for comprehensive reporting of experimental procedures [7].

Background and Principle

XPS is based on the photoelectric effect. An X-ray beam irradiates the sample, ejecting core-level electrons (photoelectons). The kinetic energy of these ejected electrons is measured, and the binding energy is calculated. The binding energy is characteristic of a specific element and its chemical environment, providing both elemental and chemical state information. The technique is surface-sensitive because only electrons emitted from the top ~10 nm of the material can escape without losing energy [3].

Materials and Reagents

Table 2: Research Reagent Solutions and Essential Materials for XPS

| Item Name | Function / Explanation |

|---|---|

| XPS Instrument | The main apparatus, comprising an X-ray source, an electron energy analyzer, an ultra-high vacuum (UHV) chamber, and an electron detector. |

| Solid Sample | A conductive or semi-conductive material, or a non-conductor if charge compensation is available. Must be compatible with UHV. |

| Adhesive Conductive Tape | Used for mounting powdered samples or ensuring electrical contact between the sample and the holder to prevent charging. |

| Sample Holder (Stub) | A metal platform designed to securely hold the sample within the UHV chamber. |

| Argon Gas (Ar⁺) | Used in an ion gun for sputter cleaning the sample surface or for depth profiling by sequentially removing surface layers. |

| Reference Samples | Samples with known, well-defined surface composition (e.g., gold or clean silicon) for instrument calibration and energy scale verification. |

Step-by-Step Procedure

Sample Preparation:

- Handling: Wear powder-free nitrile gloves to avoid contamination.

- Cleaning: If necessary, clean the sample surface with volatile, non-residue-leaving solvents (e.g., high-purity isopropanol) in a dust-free environment to remove atmospheric contaminants.

- Mounting: Securely mount the sample onto the appropriate sample holder using conductive tape. Ensure good electrical contact, especially for insulating samples.

- Insertion: Transfer the mounted sample into the introduction chamber (load-lock) of the XPS system.

Instrument Setup:

- Pump-down: Evacuate the introduction chamber to a pressure typically better than 1 x 10⁻⁶ mbar before transferring the sample into the main UHV analysis chamber (pressure < 1 x 10⁻⁹ mbar).

- X-ray Source Selection: Select the anode for the X-ray source. Common choices are Mg Kα (1253.6 eV) or Al Kα (1486.6 eV). Ensure the X-ray source is energized and stable.

- Calibration: Use a reference sample (e.g., clean gold foil) to calibrate the energy scale of the spectrometer by measuring the Au 4f₇/₂ peak and setting its binding energy to 84.0 eV.

Data Acquisition:

- Survey Spectrum: Acquire a wide-energy-range (e.g., 0-1100 eV binding energy) survey spectrum to identify all elements present on the surface.

- High-Resolution Spectra: For each element of interest identified in the survey scan, acquire a high-resolution spectrum over a narrow energy range. Use a lower pass energy for better energy resolution.

- Parameters: Typical parameters might include: 20-50 eV pass energy for high-resolution scans, 0.05-0.1 eV step size, and acquisition time sufficient to achieve a good signal-to-noise ratio.

Data Analysis:

- Peak Identification: Identify the elements present by matching the binding energies of the peaks in the survey spectrum to known core-level energies.

- Chemical Shift Analysis: For high-resolution spectra, note the precise binding energy of peaks. Shifts from the elemental binding energy indicate the chemical state (e.g., oxidation state).

- Quantification: Use the peak areas and relative sensitivity factors (RSFs) provided by the instrument software to calculate the atomic concentration of each element.

Visualization of Workflow

The following diagram illustrates the logical workflow of an XPS experiment, from sample preparation to data interpretation.

Advanced Concepts and Applications

Modeling Surface Activity: 3D Activity Landscapes

In fields like drug development, the concept of Activity Landscapes (ALs) is used to model and visualize the relationship between the chemical structure of compounds and their biological potency [5]. A 3D AL is a graphical representation where a hypersurface is constructed in a chemical descriptor space, with the topography of the landscape revealing key Structure-Activity Relationship (SAR) characteristics.

- Mountains and Peaks: Represent regions of SAR discontinuity, where small chemical modifications lead to large changes in potency. The most prominent peaks are known as activity cliffs, formed by structurally similar compounds with large potency differences [5].

- Plains and Valleys: Represent regions of SAR continuity, where a series of chemical modifications are accompanied by only small to moderate changes in potency [5].

Quantitative comparison of these 3D ALs, by converting them into color-coded heatmaps and systematically extracting topological features, allows researchers to objectively compare the SAR information content of different compound data sets, moving beyond subjective visual assessment [5]. This is crucial for understanding the heterogeneity and complexity of SARs in drug discovery.

Visualization of Activity Landscape Concepts

The following diagram illustrates the key topological features of a 3D Activity Landscape and their relationship to SAR characteristics.

Quantitative Comparison of Activity Landscapes

Advanced computational methods enable the quantitative comparison of 3D ALs, which is essential for systematic SAR exploration. The process involves:

- Image Transformation: Converting 3D AL images into color-coded heatmaps (top-down views) where pixel intensity represents potency [5].

- Feature Extraction: Using algorithms like the marching squares algorithm (MSA) to systematically extract shape features (contours representing peaks and valleys) from the heatmaps [5].

- Similarity Quantification: Comparing the extracted feature vectors from different ALs using metrics like the weighted Jaccard coefficient (Jw) to provide a numerical measure of AL (dis)similarity, thus quantifying topological relationships and, by extension, SAR information content [5].

This quantitative approach allows researchers to differentiate between data sets in a rigorous, reproducible manner, identifying which compound sets have similar or divergent SAR characteristics.

Surface science is an interdisciplinary field fundamental to advancements in materials science, heterogeneous catalysis, and nanotechnology. For researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, a deep conceptual understanding must be coupled with practical problem-solving abilities. Textbooks with integrated exercises provide a critical pathway from theoretical knowledge to applied competence, enabling professionals to analyze experimental data, characterize material interfaces, and design novel surface-mediated processes. This structured approach to learning is particularly vital in surface science, where theoretical concepts often require visualization of complex atomic structures and interpretation of sophisticated analytical instrument data.

The following analysis examines key textbooks and resources that reinforce learning through integrated problems, data analysis exercises, and practical methodologies. These materials are selected for their technical rigor and relevance to research applications, providing a foundation for both self-study and professional development in surface-driven technologies.

Critical Analysis of Surface Science Textbooks with Integrated Exercises

A comparative analysis of core textbooks reveals distinct approaches to integrating problem sets with conceptual learning. The table below summarizes key textbooks quantitatively assessed for their exercise integration and technical depth.

Table 1: Quantitative Analysis of Surface Science Textbooks with Integrated Exercises

| Textbook Title | Publication Year | Target Audience | Problem Types | Technical Focus Areas |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Surface Science: An Introduction [1] | 2003 | Advanced undergraduates, graduate students, entering researchers | End-of-chapter problems and exercises [1] | Surface analysis, diffraction, electron spectroscopy, ion probes, microscopy, adsorption, desorption, thin films [1] |

| Modern Techniques of Surface Science [8] | 2016 (3rd Edition) | Researchers, practitioners, senior undergraduates | Comparative technique analysis, research question-driven learning [8] | Surface composition, structure, electronic structure, microstructure, adsorbate characterization [8] |

2.1 Surface Science: An Introduction This textbook by Oura et al. provides a comprehensive overview, successfully balancing accessibility for beginners with technical comprehensiveness [1]. Its pedagogical approach is anchored by "end of chapter problems for the student," making it particularly suitable for systematic study [1]. The content progresses logically from foundational concepts like two-dimensional crystallography to advanced topics including surface diffusion and nanostructures, all supported by extensive visual aids with 372 figures to illustrate complex concepts [1]. Its strength lies in covering the most important aspects of modern surface science while emphasizing fundamental physical principles, making it an excellent foundational resource with practical exercises.

2.2 Modern Techniques of Surface Science The third edition of this work by D.P. Woodruff is organized around solving specific research questions rather than simply describing techniques [8]. This paradigm shifts learning from passive reception to active application, which is a more sophisticated form of exercise integration. Each chapter compares different characterization techniques for addressing particular analytical challenges, such as determining surface composition or molecular adsorption properties [8]. This structure trains researchers to select the most appropriate techniques for their specific needs, developing crucial experimental design skills that directly benefit professionals in drug development and materials science.

Experimental Methodologies and Protocols in Surface Science

Surface science experimentation requires sophisticated protocols for reproducible and meaningful results. The following workflow represents a generalized methodology for surface analysis, integrating multiple techniques discussed in the recommended textbooks.

Diagram 1: Surface Analysis Workflow

3.1 Detailed Protocol: Surface Crystallography via Low-Energy Electron Diffraction (LEED) This protocol outlines the procedure for determining surface structure, a fundamental capability in surface science research.

Objective: To determine the two-dimensional periodicity and atomic arrangement of a crystal surface.

Materials and Reagents:

- Ultra-High Vacuum (UHV) Chamber: Maintains pressure < 10⁻¹⁰ mbar to prevent surface contamination.

- LEED Optics: Consists of electron gun, hemispherical grids, and phosphorescent screen.

- Single Crystal Sample: Oriented and polished to within 0.1° of desired crystallographic plane.

- Sample Holder: With precision heating (to 1500 K) and cooling (to 100 K) capabilities.

- Transfer Arm: For moving samples between preparation and analysis positions.

Procedure:

- Sample Preparation: Mount the single crystal on the holder. Introduce into UHV system.

- Surface Cleaning: Cycle repeatedly until surface is clean:

- Sputtering: Expose surface to 1-5 keV Ar⁺ ions for 10-30 minutes.

- Annealing: Heat to recrystallization temperature (typically 2/3 of melting point) for 1-5 minutes.

- Surface Quality Verification: Monitor surface composition using Auger Electron Spectroscopy (AES) until contamination levels are below 1% monolayer.

- LEED Measurement:

- Align sample normal with LEED optics axis.

- Set electron beam energy to range 20-200 eV.

- Adjust beam current to 0.1-1 μA to visualize pattern without sample damage.

- Record diffraction pattern images at multiple energies.

- Data Analysis:

- Measure spot positions to determine surface unit cell dimensions and symmetry.

- Analyze spot intensities versus beam energy (IV-LEED) for structural determination.

- Compare experimental IV curves with multiple-scattering calculations to refine atomic coordinates.

Troubleshooting:

- Poor Pattern Quality: May indicate residual contamination; repeat cleaning cycles.

- High Background: Suggests disordered surface; optimize annealing temperature and duration.

- Streaked Patterns: Often indicates step arrays; verify surface miscut angle.

Essential Research Reagent Solutions and Materials

Surface science research requires specialized materials and reagents for sample preparation, modification, and analysis. The following table details key resources for experimental work.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for Surface Science Experiments

| Reagent/Material | Technical Function | Application Example |

|---|---|---|

| Single Crystal Surfaces | Provides well-defined, ordered substrates for fundamental studies of surface phenomena [1]. | Metal single crystals (Pt, Au, Cu) for catalysis studies; semiconductor wafers (Si, GaAs) for electronics. |

| Sputtering Gases | Creates energetic ions for surface cleaning and depth profiling through momentum transfer. | High-purity Argon (Ar) for general sputtering; Krypton (Kr) for heavier elements; Oxygen (O₂) for reactive sputtering. |

| Calibration Standards | Enables quantitative analysis and instrument response calibration for surface spectroscopy. | Au, Ag, Cu foils for XPS energy calibration; Si/MoO₃ for work function measurements; gratings for spatial calibration. |

| Molecular Adsorbates | Serves as probe molecules for studying adsorption energetics and surface reaction mechanisms. | CO for metal site titration; H₂ for hydrogenation studies; H₂O for hydrophilicity; organic vapors for sensor development. |

Conceptual Framework of Surface Science Domains

Surface science integrates multiple disciplinary approaches and conceptual domains. The following diagram maps these interrelationships and their connection to core analytical techniques.

Diagram 2: Surface Science Conceptual Framework

For researchers and drug development professionals, textbooks with integrated exercises provide more than academic training—they develop the analytical mindset required to tackle complex surface-related challenges in applied settings. Resources like Surface Science: An Introduction offer foundational problem-solving skills, while advanced texts like Modern Techniques of Surface Science cultivate the technique selection and experimental design capabilities crucial for innovation. The protocols and methodologies detailed herein provide a framework for translating theoretical knowledge into practical expertise, enabling professionals to characterize material surfaces, optimize catalytic processes, and develop surface-modified drug delivery systems with greater scientific rigor.

Surface science provides the critical framework for understanding molecular interactions at interfaces, a fundamental concept for advancements in catalysis, semiconductor technology, and pharmaceutical development [1]. This discipline bridges the gap between the idealized world of bulk crystalline structures and the complex reality of surface phenomena. A comprehensive curriculum in this field systematically progresses from the well-defined principles of two-dimensional (2D) crystallography to the intricate details of electronic structure at surfaces [1]. This foundational knowledge is indispensable for researchers and scientists engaged in rational drug design, where surface interactions determine binding affinity and specificity. The following sections delineate the core curriculum, supported by quantitative data, detailed experimental protocols, and essential analytical workflows to equip professionals with the necessary tools for cutting-edge research.

Foundational Concepts: 2D Surface Crystallography

The study of surface science begins with 2D crystallography, which describes the periodic arrangement of atoms on a surface. Unlike bulk 3D crystals, surface structures can exhibit reconstructions and adsorbates that lead to unique symmetries and properties [1].

Key Concepts and Notation:

- Substrate and Overlayers: The surface structure is defined relative to the underlying bulk crystal. An overlayer, such as an adsorbed gas molecule, may form a periodic structure described by a specific notation.

- Wood's Notation: This is a standard method for describing surface structures. It defines the overlayer's periodicity relative to the substrate's primitive lattice vectors. A structure is denoted as ( M(hkl)m \times n R\beta^\circ - A ), where:

- ( M ) is the chemical symbol of the substrate.

- ( (hkl) ) is the Miller index of the surface plane.

- ( m ) and ( n ) describe the periodicity of the overlayer.

- ( R\beta^\circ ) indicates a rotation of the overlayer by ( \beta ) degrees relative to the substrate.

- ( A ) is the chemical symbol of the adsorbate.

Table 1: Common 2D Bravais Lattices and Their Properties

| Lattice Type | Unit Cell Axes and Angles | Examples of Observed Surface Structures |

|---|---|---|

| Hexagonal | ( |a1| = |a2| ), ( \gamma = 120^\circ ) | Graphite(0001), HCP(0001) metal surfaces (e.g., Ru) |

| Square | ( |a1| = |a2| ), ( \gamma = 90^\circ ) | Fe(100), Ni(100) |

| Rectangular | ( |a1| \neq |a2| ), ( \gamma = 90^\circ ) | Reconstructed Au(110) 1x2 |

| Oblique | ( |a1| \neq |a2| ), ( \gamma \neq 90^\circ ) | Rare on clean metals, possible with complex organic adsorbates |

Experimental Determination of Surface Structure

A suite of advanced analytical techniques is employed to determine surface structure and composition. These methods provide complementary information, from long-range periodicity to chemical identity.

Table 2: Core Surface Science Techniques and Applications

| Technique | Primary Physical Principle | Key Information Obtained | Typical Experimental Parameters |

|---|---|---|---|

| Low-Energy Electron Diffraction (LEED) | Elastic backscattering of low-energy electrons (10-500 eV) | 2D surface periodicity, unit cell size and symmetry, presence of reconstruction | UHV conditions (< ( 10^{-10} ) Torr), electron beam current 0.1-1 μA, sample at room temperature or cooled/heated |

| X-ray Photoelectron Spectroscopy (XPS) | Photoelectric effect induced by X-rays | Elemental composition, chemical oxidation state, empirical formula | Monochromatic Al Kα (1486.6 eV) or Mg Kα (1253.6 eV) source, UHV, pass energy 20-100 eV for high resolution |

| Scanning Tunneling Microscopy (STM) | Quantum tunneling between a sharp tip and conductive sample | Real-space atomic-scale topography, local electronic density of states | UHV, constant current mode: bias voltage 10 mV - 2 V, tunneling current 0.1-5 nA |

From Structure to Electronic Properties

The atomic structure of a surface directly dictates its electronic properties. Surface states, which are electronic states localized at the surface, arise due to the termination of the bulk crystal lattice. These states are highly sensitive to atomic geometry and the presence of adsorbates, making them critical for understanding chemical reactivity [1].

Key Electronic Structure Concepts:

- Surface States: Electronic states localized at the surface, found in band gaps of the bulk crystal projected band structure.

- Work Function (( \Phi )): The minimum energy required to remove an electron from the solid to a point in vacuum far outside the surface. It is sensitive to surface crystallography, reconstruction, and adsorbates.

- Surface Core-Level Shift (SCLS): In XPS, the binding energy shift of core-level electrons from surface atoms compared to bulk atoms, due to their different coordination and chemical environment.

Advanced Crystallographic Data Collection for Structure Solution

For the definitive 3D atomic structure determination of surface-adsorbed molecules or thin films, single-crystal X-ray diffraction is the gold standard. The quality of the diffraction data set is paramount and is characterized by several key metrics [9].

Table 3: Data Quality Requirements for Different Crystallographic Applications

| Crystallographic Method | Recommended Resolution Limit | Required Completeness | Optimal Redundancy | Primary Application in Surface Science |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Small Molecule SXRD | As high as the crystal provides (often <1.0 Å) | > 95% for overall and shell with highest I/σ | 4-10 | Determining atomic coordinates of adsorbed ligands or small molecules on surfaces. |

| Anomalous Dispersion (SAD/MAD) | Not the highest priority; focus on accuracy | High completeness at low resolution is critical | As high as possible | Locating specific heavy atoms (e.g., in metal-organic frameworks or organometallic surface complexes). |

| Molecular Replacement (MR) | Moderate (e.g., 1.5-2.5 Å) | High completeness for strong, low-resolution reflections | Moderate (e.g., 2-4) | Solving structures of proteins or large biomolecules with known homologs, relevant to membrane protein studies. |

Experimental Protocol: Data Collection for High-Resolution Structure Refinement [9] [10]

Crystal Selection and Mounting: Select a single, well-formed crystal under a microscope. For surface-grown crystals, this may involve mounting on a specialized loop. Flash-cool the crystal in a stream of nitrogen gas at 100 K to mitigate radiation damage.

Strategy Calculation:

- Collect a preliminary test image (e.g., 0.5-1° oscillation).

- Auto-index the image to determine the crystal's unit cell and orientation matrix.

- Use a data collection strategy program (e.g., within the PILATUS or EIGER detector software suite) to determine the optimal starting angle and total rotation range to maximize completeness and minimize redundancy.

Data Collection Parameters:

- Wavelength: Typically use a standard source (e.g., Mo Kα = 0.71073 Å or Cu Kα = 1.54184 Å for laboratory systems; ~1.0 Å at synchrotrons).

- Detector Distance: Set to achieve the desired resolution (e.g., a shorter distance for higher resolution, ensuring reflections at the detector edge do not overlap).

- Exposure Time and Rotation per Image: Balance to achieve I/σ(I) > 2 in the highest-resolution shell while avoiding saturation of strong, low-resolution reflections. A fine φ-slice (e.g., 0.1-0.5°) is optimal for modern photon-counting detectors.

- Total Rotation Range: Typically 180° to 360° to ensure a complete data set, as dictated by the strategy calculation.

Data Processing:

- Process the diffraction images using software like XDS or CCP4.

- Integrate spot intensities and scale the data to correct for experimental variations.

- The final output is a file of structure factors (( F{hkl} )) and their estimated uncertainties (( σ(F{hkl}) )), which are used for subsequent structure solution and refinement.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

Table 4: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Surface Science and Crystallography

| Item / Reagent | Function and Explanation |

|---|---|

| Single-Crystal Substrates | Provide a well-defined, atomically flat surface for the growth of thin films or study of adsorbates. Examples include Au(111), Si(100), and HOPG (Highly Oriented Pyrolytic Graphite). |

| High-Purity Gases (e.g., CO, H₂, O₂) | Used as controlled adsorbates to study surface reactions, catalytic cycles, or to functionalize a surface for subsequent crystal growth. |

| Cryogenic Coolants (Liquid N₂) | Essential for flash-cooling crystals to ~100 K during X-ray data collection to reduce radiation damage and preserve crystal order [10]. |

| Selenomethionine | An amino acid used in protein expression for incorporation into proteins. Its selenium atom provides a strong anomalous scattering signal for SAD/MAD phasing to solve the phase problem in macromolecular crystallography [10]. |

| Synchrotron Radiation Beamtime | Provides high-flux, tunable X-ray beams essential for collecting high-resolution and anomalous diffraction data, especially for challenging samples like thin films or weakly diffracting crystals [10]. |

Visualization of Workflows and Relationships

The following diagrams, generated using Graphviz DOT language, illustrate the core experimental and logical pathways in surface science.

Diagram 1: Surface Analysis Techniques Workflow

Diagram 2: Crystallographic Data Collection Protocol

Mastering Techniques and Their Real-World Applications

Comprehensive Guides to Surface Analysis Techniques (XPS, AES, SIMS, etc.)

Surface analysis techniques are indispensable tools in modern materials science, nanotechnology, and industrial research, enabling the characterization of the outermost layers of materials where critical processes occur. These techniques provide vital information about elemental composition, chemical bonding, molecular structure, and topography at scales ranging from micrometers to nanometers. The field has evolved significantly over recent decades, with technological advancements pushing detection limits and spatial resolution to new frontiers. Current market analysis indicates substantial growth in the surface analysis sector, with the global X-ray Photoelectron Spectroscopy (XPS) market alone projected to be worth USD 824.3 million in 2025 and expected to achieve USD 974.5 million by 2034 with a CAGR of 1.9% [11]. This growth is driven by increasing demands from semiconductor, materials science, and biomedical sectors where understanding surface properties is essential for product development and innovation.

The strategic importance of surface analysis spans multiple industries. In semiconductors, these techniques enable characterization of nanoscale features and contamination control. In biomedicine, they facilitate the study of implant surfaces and drug-polymer interactions. For energy applications, they reveal degradation mechanisms in batteries and fuel cells. Each technique offers unique capabilities and limitations, making technique selection a critical step in experimental design. This guide provides a comprehensive overview of major surface analysis methods, their operating principles, applications, and practical implementation considerations to assist researchers in selecting the most appropriate methodology for their specific research needs.

Fundamental Principles of Surface Analysis

Surface analysis techniques probe the outermost atomic layers of materials (typically 1-10 nm) using various incident particles (photons, electrons, or ions) and detect the ejected particles to obtain compositional and chemical information. The fundamental principle underlying all surface analysis methods is that the interaction between an incident probe and a material surface produces emitted particles or radiation that carries characteristic information about the surface. The depth sensitivity of these techniques arises from the limited escape depth of the emitted particles, which for electrons is typically a few nanometers, making them exceptionally surface-sensitive.

The most common surface analysis approaches can be categorized by their probe and detection mechanisms. Electron spectroscopy techniques, including XPS and Auger Electron Spectroscopy (AES), use X-rays or electrons to eject electrons from core levels of surface atoms, with the kinetic energy of these electrons providing elemental and chemical state information. I spectroscopy techniques, such as Secondary Ion Mass Spectrometry (SIMS), use focused ion beams to sputter and ionize surface atoms, which are then analyzed by mass spectrometry. Ion scattering techniques, including Rutherford Backscattering Spectroscopy (RBS) and Ion Scattering Spectroscopy (ISS), use ion beams and analyze the energy distribution of scattered ions to determine surface composition and structure.

Each technique has distinct information depths, detection limits, and capabilities for elemental identification, quantification, and chemical state analysis. The choice of technique depends on the specific analytical requirements, including the need for spatial resolution, depth profiling, sensitivity, and the types of materials being analyzed. Understanding these fundamental principles is essential for selecting the most appropriate technique and correctly interpreting the resulting data.

Major Surface Analysis Techniques

X-ray Photoelectron Spectroscopy (XPS)

XPS is the most widely used surface analysis technique, with more than 6,500 operational instruments installed worldwide as of 2024 [11]. The technique operates on the photoelectric effect principle, where a surface irradiated with X-rays emits photoelectrons whose binding energies are characteristic of specific elements and their chemical states. XPS provides quantitative elemental analysis for all elements except hydrogen and helium, with typical information depths of <10 nm [12]. Chemical state information is derived from small shifts (typically a few eV) in electron binding energies, enabling identification of oxidation states and chemical environments.

The applications of XPS span virtually all branches of science and engineering. In materials science, it characterizes surface composition of alloys, polymers, and ceramics. In the semiconductor industry, it analyzes thin films and contamination. In biomedicine, it studies protein adsorption and biomaterial surfaces. Recent advancements include high-resolution monochromatic XPS systems, which showed a 31% adoption jump from 2021 to 2024 as researchers pursued sub-1 nm surface characterization accuracy [11]. Automation has also surged by 27%, with automated sample loading reducing turnaround time by 42% in high-volume testing centers.

Despite its capabilities, XPS faces reproducibility challenges, particularly with inexperienced users. A survey of experienced XPS practitioners revealed that in many publications, XPS data are often incomplete or misinterpreted [13]. Proper instrument calibration, charge correction, and spectral interpretation are essential for reliable results. The technique requires ultra-high vacuum conditions and has limited spatial resolution compared to electron microscopy techniques. Depth profiling requires sputtering with ion guns, which can cause damage and alter chemical states.

Auger Electron Spectroscopy (AES)

AES utilizes a focused electron beam to excite atoms, resulting in the emission of Auger electrons that have characteristic energies for each element. The technique provides elemental identification and composition with high spatial resolution (down to 5 nm) and can be combined with ion sputtering for depth profiling. Unlike XPS, AES is primarily an elemental technique with limited chemical state information, though chemical effects can sometimes be observed in line shapes and positions.

The strength of AES lies in its high spatial resolution and capability for elemental mapping. When electrons are the incident particles, spatial resolution on the order of 5 nm can be achieved, enabling detailed imaging of surface heterogeneity [14]. This makes AES particularly valuable for failure analysis in semiconductors, where identifying sub-micron contamination or defects is critical. AES is also used in metallurgy to study grain boundary segregation and in catalysis to examine active sites.

Limitations of AES include potential electron beam damage, especially on sensitive organic and biological materials. Like XPS, it requires conductive samples or charge compensation for insulating materials. The technique has higher detection limits (typically 0.1-1 at%) compared to XPS and is less quantitative due to stronger matrix effects. While AES instruments can be less expensive than XPS systems, they require more operator skill for optimal analysis.

Secondary Ion Mass Spectrometry (SIMS)

SIMS uses a focused primary ion beam (typically 2-5 keV) to sputter material from the surface in high vacuum conditions (<10⁻⁷ Torr), followed by mass analysis of the ejected secondary ions [14]. The technique offers exceptional sensitivity, with detection limits in the ppb-ppm range across the periodic table, and the ability to detect all elements and isotopes. SIMS can provide molecular information through the detection of cluster ions, making it valuable for organic and biological surface analysis.

Time-of-Flight SIMS (TOF-SIMS) provides the highest spatial resolution (down to 50 nm) and mass resolution for surface analysis. Recent applications demonstrate its power in complex materials characterization, such as in battery research where XPS and TOF-SIMS chemical imaging uncovered the stabilizing effects of engineered particle battery cathodes [15]. The combination of these tools provided a comprehensive view of how coatings influence interfacial stability and degradation.

The main limitation of SIMS is its strong matrix effects, where the yield of secondary ions depends dramatically on the chemical environment. This makes quantification challenging and requires matrix-matched standards. SIMS is also inherently destructive, and the high vacuum requirement limits the analysis of volatile samples. While offering excellent depth resolution (1-10 nm), SIMS has relatively slow erosion rates (nm/min) compared to techniques like GDOES [14].

Glow Discharge Optical Emission Spectroscopy (GDOES)

GDOES utilizes a reduced-pressure plasma (a few Torr) to generate sputtering ions in situ from a low flow of argon [14]. These ions are attracted to the sample cathode, arriving with kinetic energies of ~50 eV, resulting in rapid sputtering of the surface material. The sputtered atoms are excited in the plasma and emit element-specific light that is detected by optical spectrometers.

A key advantage of GDOES is the physical separation of the sputtering and excitation mechanisms, which greatly reduces matrix effects compared to techniques like SIMS or Spark Emission [14]. Pulsed RF GDOES can analyze both conductive and non-conductive materials without charge compensation, making it suitable for oxides, glasses, and polymers. The technique offers very high erosion rates (μm/min vs. nm/min for SIMS), enabling rapid depth profiling through thick layers.

The limitations of GDOES include the lack of lateral resolution as signals are averaged over the sputtered area (several mm in diameter) [14]. Its detection limits (expressed in ppm) are higher than SIMS, and it provides primarily elemental rather than chemical state information. However, for rapid depth profiling of thin and thick films, GDOES offers unique benefits, particularly for industrial applications where speed and ease of use are prioritized.

Other Surface Analysis Techniques

Rutherford Backscattering Spectroscopy (RBS) uses high-energy ions (typically 1-2 MeV He⁺) and analyzes the energy spectrum of backscattered ions to determine elemental composition and depth distributions. RBS is quantitative without standards, has good depth resolution (10-30 nm), but has limited mass resolution for heavy elements in a light matrix and requires specialized accelerator facilities.

Ion Scattering Spectroscopy (ISS) is exceptionally surface-sensitive, probing only the outermost atomic layer. It uses low-energy ions (0.5-5 keV) and analyzes the energy of scattered ions to determine surface composition and structure. ISS is valuable for studying adsorption and catalytic processes but has limited mass resolution and quantification capabilities.

Scanning Tunneling Microscopy (STM) and Atomic Force Microscopy (AFM) provide real-space atomic-scale imaging of surface topography without the need for vacuum conditions. These scanning probe techniques can achieve atomic resolution and manipulate individual atoms but provide limited chemical information unless combined with spectroscopy methods.

Comparative Analysis of Techniques

Table 1: Comparison of Key Surface Analysis Techniques

| Technique | Information Depth | Lateral Resolution | Detection Limits | Elements Detected | Chemical Information | Destructive |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| XPS | <10 nm [12] | 5-10 μm | 0.1-1 at% | All except H, He [13] | Excellent (oxidation states, bonding) | Minimal (except during depth profiling) |

| AES | 2-5 nm | 5 nm - 50 nm [14] | 0.1-1 at% | All except H, He | Limited | Yes (electron beam damage) |

| SIMS | 10 monolayers [14] | 50 nm - 1 μm | ppb-ppm [14] | All elements and isotopes | Molecular information from clusters | Yes |

| GDOES | 100 monolayers [14] | Several mm [14] | ppm range [14] | All except H, He, Ne | Limited | Yes |

| RBS | 100 monolayers [14] | 1 mm - 1 cm | 1 at% | Heavier than matrix | Limited | Minimal |

Table 2: Operational Characteristics and Applications

| Technique | Vacuum Requirements | Analysis Speed | Quantification | Main Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| XPS | Ultra-high vacuum | Minutes to hours | Good (with standards) | Surface chemistry, thin films, contamination analysis [11] |

| AES | Ultra-high vacuum | Minutes to hours | Moderate | Failure analysis, microelectronics, grain boundary segregation |

| SIMS | Ultra-high vacuum (<10⁻⁷ Torr) [14] | Hours | Poor (strong matrix effects) | Trace analysis, dopant profiling, organic surfaces [15] |

| GDOES | Reduced pressure (a few Torr) [14] | Seconds to minutes | Good (with calibration) | Rapid depth profiling, coatings, thick films [14] |

| RBS | High vacuum | Hours | Excellent (standardless) | Thin film composition, impurity location, film thickness |

The selection of an appropriate surface analysis technique depends on the specific analytical requirements. For chemical state information and quantitative analysis of the top few nanometers, XPS is generally the preferred method. When high spatial resolution elemental mapping is required, AES offers superior capabilities. For trace element detection and isotopic analysis, SIMS is unmatched. For rapid depth profiling through thick layers, GDOES provides unique advantages. RBS offers quantitative depth profiling without standards but requires specialized facilities.

Technique complementarity is often the most effective approach for complex materials characterization. Recent studies demonstrate the power of combined approaches, such as XPS and TOF-SIMS for battery cathode analysis [15], or GD and SEM for topographic characterization [14]. Approximately 65% of GD users in Japan are also XPS users, frequently applying the techniques complementarily [14]. Such integrated methodologies leverage the strengths of each technique to provide a more complete understanding of surface properties.

Experimental Design and Workflows

Technique Selection Framework

Selecting the appropriate surface analysis technique requires systematic consideration of multiple factors. The decision workflow begins with defining the analytical question, then evaluating sample characteristics and analytical requirements.

The following diagram illustrates the decision process for selecting surface analysis techniques:

Sample Preparation Considerations

Proper sample preparation is critical for successful surface analysis. Samples must be compatible with the vacuum environment of the instrument, with minimal volatile components that could outgas and compromise vacuum integrity. Conductive samples require no special preparation for techniques like XPS and AES, but insulating samples may need charge compensation strategies such as thin metal coatings, low-flux electron floods, or the use of charge-neutralizing filaments.

For depth profiling applications, surface roughness should be minimized as it degrades depth resolution. Cross-sectioning may be required for interface analysis, followed by careful polishing to maintain interface integrity. SIMS analysis of organic materials often requires special handling to preserve molecular information and minimize beam-induced damage. In all cases, representative sampling and minimization of surface contamination during preparation are essential for meaningful results.

Data Collection Strategies

Effective data collection begins with defining the analysis objectives and developing a measurement plan. For XPS, this typically involves collecting survey spectra to identify all elements present, followed by high-energy-resolution regional scans for quantitative analysis and chemical state identification. The amount of data to collect should provide adequate statistics and reproducibility, with careful consideration of potential specimen damage from the X-ray source or charge neutralization system [13].

Depth profiling requires optimization of sputtering parameters to balance depth resolution and analysis time. In techniques like SIMS and AES, alternating between data collection and sputtering enables reconstruction of composition versus depth. For GDOES, continuous monitoring of optical emissions during sputtering provides real-time depth profiles. Imaging applications require balancing spatial resolution, field of view, and signal-to-noise ratios, with modern instruments offering automated large-area mapping capabilities.

Advanced Applications and Case Studies

Battery Interface Engineering

The combination of XPS and TOF-SIMS has proven invaluable for studying interfacial processes in advanced battery systems. In one case study, researchers used these techniques to analyze engineered particle (Ep) battery cathodes, revealing how specialized coatings stabilize interfaces and reduce degradation in lithium metal batteries [15]. XPS provided chemical state information about the solid-electrolyte interface (SEI) composition, while TOF-SIMS delivered high-resolution mapping of lithium distribution and detection of trace degradation products.

The study demonstrated that Ep-coated cathodes exhibit more uniform and controlled interfaces, leading to improved battery performance and long-term stability. This application highlights how complementary techniques can address complex materials challenges where multiple length scales and information types are required. Battery research centers reported a 29% increase in XPS-based SEI studies between 2021 and 2024, reflecting growing reliance on surface analysis for energy storage development [11].

Semiconductor Process Control

Surface analysis techniques play a critical role in semiconductor manufacturing, where contamination layers under 0.5 nm can disrupt device yields at nodes below 7 nm [11]. XPS is extensively used for contamination studies, thin film characterization, and process monitoring. Semiconductor and microelectronics facilities account for 28% of global XPS utilization, driven by fabrication requirements for sub-nanometer chemical depth profiling [11].

AES provides failure analysis capabilities with the spatial resolution needed to identify sub-micron defects and contamination. The semiconductor industry has seen a 19% increase in in-line XPS systems from 2021 to 2024, reflecting the integration of surface analysis into fabrication processes [11]. These applications demonstrate how surface analysis techniques have evolved from research tools to essential components of high-volume manufacturing.

Thin Film and Coating Analysis

GDOES has found particular utility in the analysis of thin films and coatings, where its rapid sputtering capabilities (1-10 μm/min) enable efficient depth profiling through thick layers [14]. The technique's ability to sputter both conductive and non-conductive surfaces with Ar⁺ ions of very low energies (less than 50 eV) and high current densities makes it suitable for diverse materials systems [14].

Recent advances include the use of GD sputtering for sample preparation for SEM analysis, creating sharp steps along boundaries of different materials due to differential sputtering effects [14]. This application demonstrates the expanding role of surface analysis techniques beyond characterization to include sample preparation for other analytical methods.

Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for Surface Analysis

| Material/Reagent | Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Argon Gas (High Purity) | Sputtering gas for depth profiling | Used in SIMS, XPS, AES, and GDOES; purity critical for minimizing contamination |

| Electron Flood Guns | Charge compensation for insulating samples | Essential for XPS analysis of polymers, ceramics, and biological materials |

| Reference Standards | Energy scale calibration and quantification | Au, Ag, Cu standards for XPS/AES; ion-implanted standards for SIMS |

| Conductive Adhesive Tapes | Sample mounting | Carbon tapes preferred for minimal background; specific tapes for UHV compatibility |

| Specialized Ion Sources | Sputtering and primary ion generation | Cesium, oxygen, and argon sources for different applications in SIMS and depth profiling |

| Charge Neutralizing Filaments | Surface charge control | Electron-emitting filaments for analysis of insulating samples in XPS |

| Certified Reference Materials | Method validation and quantification | NIST-traceable standards for quality assurance in quantitative analysis |

Future Perspectives and Emerging Trends

The field of surface analysis continues to evolve with several emerging trends shaping its future direction. Automation and hybrid analysis integration grew 32% year-over-year, with AI-enabled spectral analytics rising 27% [11]. These developments are making surface analysis more accessible while improving data quality and interpretation. Multi-technique platforms integrating XPS, AES, and SIMS expanded by 22%, addressing cross-correlation needs for advanced nanostructure verification [11].

Instrument performance continues to advance, with recent releases showing 22% higher energy resolution, 18% faster acquisition speeds, 15% lower instrument noise, and 24% improved surface sensitivity [11]. These improvements enable more precise characterization of increasingly complex materials systems. The growing integration of surface analysis with other characterization methods, such as the combination of Raman spectroscopy with AFM and SEM [16], provides more comprehensive materials characterization capabilities.

As materials systems become more complex and nanoscale features become increasingly important across industries, surface analysis techniques will continue to play a critical role in materials development and failure analysis. The challenge of reproducibility highlighted by experienced practitioners [13] is being addressed through improved training, standardization, and the development of best practice guides. These efforts will ensure that surface analysis remains a reliable and essential tool for scientific discovery and technological innovation.

Methodology for Pharmaceutical and Biopharmaceutical Sample Analysis

In the pharmaceutical and biopharmaceutical industries, robust analytical methodologies are fundamental to ensuring the quality, safety, and efficacy of drug substances and products. Analytical method validation (AMV) is a required process for all methods used to test final containers (release and stability testing), raw materials, in-process materials, and excipients [17]. The International Council for Harmonisation (ICH) guidelines Q2A and Q2B, along with the United States Pharmacopoeia (USP) general chapter <1225>, provide the primary framework for this validation, establishing performance characteristics that demonstrate a method's suitability for its intended use [17]. Within a broader surface science research context, these analytical techniques provide the essential tools for characterizing solid-state properties, surface interactions, and material compositions critical to drug product performance. This guide details the core methodologies, their validation, and application in the modern pharmaceutical landscape.

Core Analytical Techniques and Their Applications

A suite of analytical techniques is employed to characterize the complex attributes of pharmaceuticals, ranging from small molecules to large biological molecules like monoclonal antibodies and recombinant proteins [18].

High-Performance Liquid Chromatography (HPLC)

High-Performance Liquid Chromatography (HPLC) is an indispensable analytical technique in the biopharmaceutical industry, crucial for the separation, identification, and quantification of complex biological molecules [18]. It offers high resolution and sensitivity, allowing for the detection of small quantities of compounds in complex samples. Its versatility is evident in its various operational modes, each suited for specific analytical purposes as detailed in Table 1 [18].

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of Chromatographic Methods in Biopharmaceuticals

| Method | Primary Purpose | Key Features | Common Challenges |

|---|---|---|---|

| Reversed-Phase (RPC) | Separates proteins, peptides, and other biomolecules based on hydrophobicity [18]. | Uses hydrophobic stationary phase (e.g., C18) and polar mobile phase [18]. | Potential protein denaturation; requires optimization of organic solvent gradient. |

| Size-Exclusion (SEC) | Determines aggregation status and molecular weight distribution [18]. | Separates molecules based on their size in solution [18]. | Limited resolution; potential for non-size-based interactions with the resin. |

| Ion-Exchange (IEX) | Assesses charge variants of proteins [18]. | Separates molecules based on surface charge using ionic stationary phases [18]. | Sensitivity to mobile phase pH and ionic strength. |

| Affinity Chromatography | Protein purification and quantification (titer) [18]. | Uses specific biological interactions (e.g., Protein A for antibodies) [18]. | Requires specific ligands; elution conditions (low pH) can damage proteins. |

The workflow for developing and applying an HPLC method involves careful optimization of parameters such as the stationary phase selection, mobile phase composition (often a mixture of water and organic solvents with additives like trifluoroacetic acid), flow rate, gradient profile, and column temperature [18]. Recent advancements, such as ultra-high-performance liquid chromatography (UHPLC) and hybrid systems coupled with mass spectrometry, continue to enhance the sensitivity, resolution, and speed of these analyses [18].

Affinity Chromatography

Affinity chromatography is a highly specific technique where the stationary phase is composed of a solid support matrix embedded with immobilized ligands that specifically bind to the target protein [18]. Common ligands include Protein A, G, and L, which are extensively used for antibody purification. Protein A, for instance, specifically targets the Fc region of antibodies, making it a standard platform for monoclonal antibody (mAb) purification [18].

A typical analytical-scale Protein A affinity chromatography protocol for determining antibody titer in cell culture fluid is as follows [18]:

- Column Equilibration: The Protein A affinity column is equilibrated with a mobile phase buffer at approximately pH 7.5.

- Sample Application: The sample (e.g., cell culture fluid harvest) is introduced onto the column. The target antibodies bind specifically to the Protein A ligand.

- Washing: The column is washed with the equilibration buffer to remove non-specifically bound proteins and other contaminants.

- Elution: The bound target protein is eluted using a low-pH mobile phase (e.g., pH 3-4). This typically results in a single, sharp peak in the chromatogram.

- Sample Neutralization: Immediately after collection, the eluted protein fraction is neutralized using a buffer such as 1 M Tris-HCl (pH 9.0) to prevent acid-induced conformational changes or degradation.

- Quantification: A standard curve is generated from injected standards of known concentration, and the titer of the sample is calculated based on this curve.

This method serves as a critical sample clean-up step and for quantifying low-abundance proteins, determining the performance of a cell culture, and calculating the proper load for purification-scale columns during production [18].

Analytical Method Validation: A Practical Guide

For any analytical method, demonstrating suitability for its intended use through validation is a regulatory requirement. The critical elements of method performance are defined by ICH guidelines [17].

Table 2: Validation Characteristics per ICH Q2A and Q2B [17]

| Validation Characteristic | Definition | Typical Validation Approach |

|---|---|---|

| Accuracy | The closeness of agreement between the accepted reference value and the value found. | Demonstrated by spiking a known quantity of reference standard into the sample matrix and calculating percent recovery. |

| Precision (Repeatability) | The closeness of agreement under the same operating conditions over a short interval of time. | Measured by multiple determinations of a homogeneous sample under ideal conditions (same analyst, instrument, day). |

| Precision (Intermediate Precision) | The precision within laboratories (e.g., different days, analysts, equipment). | Assessed by generating a data set using several operators over several days with different instruments. |

| Specificity | The ability to assess the analyte unequivocally in the presence of other components. | Demonstrated by showing no interference from the matrix, impurities, or degradation products. |

| Detection Limit (DL) | The lowest amount of analyte that can be detected, but not necessarily quantitated. | Determined by analyzing samples with decreasing concentrations until a signal-to-noise ratio of 2:1 or 3:1 is achieved. |

| Quantitation Limit (QL) | The lowest amount of analyte that can be quantified with acceptable accuracy and precision. | The lowest level of the assay range, validated by demonstrating acceptable accuracy and precision at that concentration. |

| Linearity | The ability of the method to obtain results directly proportional to the analyte concentration. | Evaluated by plotting analyte concentration versus assay response and performing linear regression analysis. |

| Range | The interval between the upper and lower concentrations of analyte for which the method has suitable accuracy, precision, and linearity. | Must bracket the product specifications, with the QL constituting the lowest point. |

The validation protocol must be designed to deliver evidence of a method's suitability through appropriate acceptance criteria, varying factors expected to change during routine testing, such as sample batches, operators, instruments, and days [17]. It is crucial that method development (AMD) is finalized before AMV begins; the validation process should not be a trial-and-error effort but a formal demonstration that all pre-defined acceptance criteria are met [17].

Experimental Workflow and Data Integrity

The journey of a biopharmaceutical from development to market relies on a complex, integrated workflow. This process generates vast amounts of data, particularly during stability testing, which can result in approximately 20,000 data points for a single product report [19]. The following diagram illustrates the core analytical workflow in the biopharmaceutical development context.

Maintaining data integrity throughout this workflow is paramount. Regulatory authorities stress that data must be complete, consistent, and accurate, adhering to the ALCOA+ principles (Attributable, Legible, Contemporaneous, Original, Accurate, plus Complete, Consistent, Enduring, and Available) [19]. A structured approach to data from source to submission reduces manual transcription errors—which can cause significant filing delays and lost revenue—and enhances credibility with health authorities [19].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

The execution of reliable analytical methods depends on a foundation of high-quality, well-characterized materials. The following table details key reagents and their critical functions in pharmaceutical analysis.

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Pharmaceutical Analysis

| Item | Function in Analysis |

|---|---|

| Reference Standards | Well-characterized substances used to calibrate instruments and validate methods; essential for demonstrating accuracy and quantifying analytes [17]. |

| Chromatography Columns | The heart of the separation system; the choice of stationary phase (e.g., C18, ion-exchange, Protein A) dictates the mechanism of separation [18]. |

| Buffers & Mobile Phase Components | Create the chemical environment for separations; pH and ionic strength are critical for maintaining protein stability and achieving resolution [18]. |

| Critical Reagents | Includes enzymes, antibodies, and other biological materials used in assays; require strict quality control and stability testing to ensure consistent performance [17]. |

| System Suitability Controls | A homogeneous sample run to ensure the test system is operating within established limits before results are considered valid [17]. |

The methodology for pharmaceutical and biopharmaceutical analysis is a sophisticated field built on a foundation of rigorous technique, thorough validation, and uncompromising data integrity. Techniques like HPLC and affinity chromatography provide the necessary tools to characterize complex molecules, while adherence to ICH guidelines ensures methods are fit-for-purpose. As the industry evolves with more complex therapeutics, the principles of robust method development, validation, and structured data management will continue to be the cornerstones of delivering safe and effective medicines to patients.

Applying Surface Characterization in Drug Discovery and Product Development

Surface characterization constitutes a critical discipline in pharmaceutical research and development, providing indispensable insights into the physical and chemical properties of materials at the molecular and microscopic levels. These techniques enable scientists to understand solid-state properties, interfacial phenomena, and material behavior that directly influence drug efficacy, stability, and manufacturability. In the context of modern drug discovery, surface analysis extends beyond traditional quality control to become an integral component of rational formulation design, enabling the development of sophisticated drug delivery systems with enhanced therapeutic outcomes.

The integration of surface characterization methodologies has become increasingly vital with the advancement of complex dosage forms such as bilayer tablets, controlled-release formulations, and nano-scale drug delivery platforms. As the pharmaceutical industry progresses toward more targeted and personalized medicines, the ability to precisely characterize surfaces and interfaces ensures that developers can correlate material attributes with critical quality parameters, ultimately accelerating the translation of drug candidates from laboratory research to commercial products.

Key Surface Characterization Techniques

Core Analytical Methodologies

Pharmaceutical development employs a diverse arsenal of surface characterization techniques, each providing unique insights into material properties. These methodologies can be categorized based on the specific information they yield about surface composition, topography, and chemical functionality.

Table 1: Major Surface Characterization Techniques in Pharmaceutical Development

| Technique | Primary Applications | Information Obtained | Typical Resolution |

|---|---|---|---|

| Confocal Raman Microscopy | Drug distribution analysis, skin permeation studies, polymorph identification | Molecular composition, spatial distribution of components, chemical imaging | Diffraction-limited (~0.5-1 μm) |

| X-ray Photoelectron Spectroscopy (XPS) | Surface elemental analysis, contaminant identification, coating uniformity | Elemental composition, chemical state, empirical formula | 10-100 μm |

| Atomic Force Microscopy (AFM) | Surface topography, nanomechanical properties, adhesion forces | 3D surface morphology, roughness parameters, mechanical properties | Atomic to 100 nm |

| Secondary Ion Mass Spectrometry (SIMS) | Trace element analysis, molecular surface mapping, impurity identification | Elemental and molecular distribution, depth profiling, interface analysis | 100 nm - 1 μm |

| Contact Angle Analysis | Surface energy determination, wettability assessment, coating quality | Hydrophilicity/hydrophobicity, surface free energy, adhesion work | Macroscopic |

Advanced Integrated Approaches

The convergence of multiple characterization techniques provides a comprehensive understanding of pharmaceutical systems. For instance, Confocal Raman Microscopy has been significantly enhanced through improved experimental protocols for sample preparation and handling, particularly in cutaneous drug delivery research [20]. Recent methodological advances have addressed challenges such as photobleaching and signal-to-noise ratio optimization through standardized procedures involving freeze-drying and careful tissue handling, enabling more accurate quantification of drug permeation through skin layers.

The implementation of Response Surface Methodology (RSM) represents another powerful approach for systematic formulation development and optimization. This statistical technique enables researchers to efficiently explore complex relationships between multiple input variables and critical quality attributes of drug products [21]. By employing experimental designs such as central composite design, RSM facilitates the development of robust formulations while minimizing experimental effort through mathematical modeling and optimization.

Experimental Protocols for Surface Analysis

Sample Preparation for Confocal Raman Microscopy in Skin Permeation Studies

Proper sample preparation is paramount for obtaining reliable surface characterization data. The following protocol, adapted from improved methodologies in cutaneous drug delivery analysis, ensures optimal results for confocal Raman microscopy in skin permeation studies [20]:

Materials Required:

- Excised human or animal skin samples (typically dermatomed to 200-500 μm thickness)

- Phosphate buffered saline (PBS) for hydration maintenance

- Optimal Cutting Temperature (OCT) compound for cryosectioning (if required)

- Liquid nitrogen for rapid freezing

- Freeze-drying apparatus

- Test compound dissolved in appropriate vehicle (e.g., propylene glycol)

- Aluminum foil or specialized sample holders

Procedure:

- Sample Mounting: Carefully mount skin samples on diffusion cells or specialized holders, ensuring the stratum corneum faces the donor compartment. Maintain skin hydration throughout with PBS-soaked gauze.

Compound Application: Apply the test formulation (e.g., 4-cyanophenol in propylene glycol) uniformly to the skin surface using positive displacement pipettes. Control application density (typically 5-10 μL/cm²).

Incubation: Maintain samples at 32°C (skin surface temperature) and 95% relative humidity for predetermined permeation periods (typically 2-24 hours).

Termination and Washing: Carefully remove excess formulation from skin surface using cotton swabs and gentle washing with PBS-surfactant solution.

Freeze-stopping: Rapidly freeze samples using liquid nitrogen to halt molecular diffusion and stabilize the drug distribution profile.

Cryosectioning (Optional): For cross-sectional analysis, embed frozen samples in OCT compound and section at 5-20 μm thickness using a cryostat microtome maintained at -20°C.

Freeze-drying: Subject frozen samples to controlled freeze-drying to remove water without altering drug distribution. Maintain temperature below -20°C during primary drying phase.

Microscopy Analysis: Mount prepared samples on microscope slides and analyze using confocal Raman system with appropriate laser wavelength and power settings to prevent photobleaching while maintaining adequate signal-to-noise ratio.

Critical Parameters:

- Consistent sample thickness across experimental groups

- Strict temperature control during permeation and processing

- Minimization of hydration-induced artifacts through controlled drying

- Standardized instrumental settings (laser power, integration time, spatial resolution)

Response Surface Methodology for Formulation Optimization

Response Surface Methodology provides a systematic approach for optimizing complex formulations with multiple interacting variables. The following protocol details the application of RSM for bilayer tablet development containing Tamsulosin (sustained release) and Finasteride (immediate release) [21]:

Experimental Design:

- Factor Identification: Select critical formulation variables as independent factors: