GISAXS for Nanoparticle Characterization: A Comprehensive Guide for Materials and Drug Development Research

This article provides a complete overview of Grazing-Incidence Small-Angle X-ray Scattering (GISAXS) for characterizing nanoparticles in thin films and at interfaces.

GISAXS for Nanoparticle Characterization: A Comprehensive Guide for Materials and Drug Development Research

Abstract

This article provides a complete overview of Grazing-Incidence Small-Angle X-ray Scattering (GISAXS) for characterizing nanoparticles in thin films and at interfaces. Tailored for researchers and drug development professionals, it covers foundational principles, practical methodologies, advanced data analysis techniques, and validation strategies. The content explores applications ranging from block copolymer nanostructures for microelectronics to real-time monitoring of nanoparticle adsorption at liquid surfaces, highlighting GISAXS as a powerful, statistically robust tool that complements high-resolution microscopy for comprehensive nanomaterial analysis.

Understanding GISAXS: Core Principles and Advantages for Nanoscale Analysis

What is GISAXS? Defining the Technique and Its Historical Development

Grazing-Incidence Small-Angle X-Ray Scattering (GISAXS) is an advanced, surface-sensitive analytical technique used to probe the nanostructure of thin films and surfaces. As a hybrid method, it combines the principles of small-angle X-ray scattering (SAXS) with the surface sensitivity of grazing-incidence diffraction, enabling the characterization of nanoscale density correlations and object shapes at surfaces or buried interfaces [1] [2]. The technique was originally introduced in 1989 by Joanna Levine and Jerry Cohen to study thin film growth, and has since evolved into a frequently used tool for investigating nanostructured materials [1] [2].

In a typical GISAXS experiment, a collimated X-ray beam strikes the sample surface at a very shallow grazing-incidence angle (typically less than 1°), which limits beam penetration to a depth ranging from a few nanometers up to approximately 100 nanometers [1] [3]. This configuration efficiently minimizes background scattering from the substrate while maximizing the signal from the surface nanostructures. The scattered X-rays are collected by a two-dimensional detector, producing a pattern that encodes information about the size, shape, and arrangement of nanoscale features over a statistically representative sample area [1] [4].

Table 1: Key Characteristics of GISAXS

| Parameter | Typical Range | Significance |

|---|---|---|

| Incidence Angle (αᵢ) | 0.05° - 1.0° | Governs penetration depth and surface sensitivity [1] [3] |

| Scattering Angles (2θ) | Up to 5° | Probes structures at nanoscale lengths [1] |

| Penetration Depth | Few nm to ~100 nm | Controlled by varying incidence angle [1] |

| Probed Sample Area | Several mm² | Provides statistically representative data [1] [3] |

Compared to local probe techniques like atomic force microscopy (AFM) and transmission electron microscopy (TEM), GISAXS provides averaged, representative structural information from a large sample area, making it an ideal complement for comprehensive nanomaterial characterization [1]. The technique is widely applicable to diverse material systems including porous materials, metals, semiconductors, polymers, and biological materials attached to surfaces [1] [2].

Historical Development and Technique Evolution

The development of GISAXS represents a significant milestone in surface science, enabling researchers to statistically analyze nanostructures that were previously only observable through local probe techniques. Since its introduction in 1989 by Levine and Cohen for studying dewetting of gold on glass, the technique has expanded rapidly with the growing interest in nanoscience [1] [2].

The initial applications focused primarily on hard matter systems, including the characterization of quantum dots on semiconductor surfaces and in-situ studies of metal deposits on oxide surfaces [2]. As the technique matured, its applications broadened to include soft matter systems such as ultrathin polymer films, block copolymer films, and other self-organized nanostructured thin films that are crucial for modern nanotechnology [2]. Future development challenges may include expanded biological applications, such as studying proteins, peptides, or viruses attached to surfaces or incorporated into lipid layers [2].

Table 2: Evolution of GISAXS Applications

| Time Period | Primary Applications | Material Systems |

|---|---|---|

| 1989 (Introduction) | Thin film growth, dewetting processes [1] [2] | Metal layers on glass [2] |

| 1990s | Metal agglomerates on surfaces, buried interfaces [2] | Hard matter systems, semiconductors |

| 2000s | In-situ growth studies, self-organized nanostructures [2] | Quantum dots, block copolymers, polymers |

| 2010s-Present | Complex nanostructures, biological hybrids, real-time processes | Mesoporous films, biological materials, soft matter [1] [2] |

The theoretical framework for interpreting GISAXS data has also advanced significantly. While initial analysis borrowed heavily from transmission SAXS, the community developed more sophisticated approaches based on the Distorted-Wave Born Approximation (DWBA) to properly account for the unique scattering geometry and multiple reflection effects that occur at grazing incidence [2] [5]. This theoretical foundation enables researchers to accurately interpret complex scattering patterns and extract quantitative structural parameters.

Instrumentally, GISAXS has progressed from specialized synchrotron beamlines to include laboratory-based systems, increasing accessibility for researchers [1]. Recent developments include high-throughput robotic systems for automated data collection [6] and specialized variants like GTSAXS (Grazing-incidence Transmission SAXS) that simplify data analysis by reducing multiple scattering effects [7].

Technical Foundations and Methodology

Fundamental Principles

GISAXS leverages the same fundamental physical principles as conventional SAXS but adapts them for surface sensitivity through a specialized geometric configuration. When X-rays interact with matter at grazing incidence, several unique effects occur that differentiate GISAXS from transmission scattering techniques:

- Evanescent Wave Propagation: Below the critical angle, X-rays undergo total external reflection, creating an evanescent wave that propagates along the surface and probes only a shallow depth of a few nanometers [3].

- Intensity Enhancement: Multiple factors contribute to signal enhancement in GISAXS, including beam projection effects that illuminate a larger sample volume, waveguiding phenomena near the critical angle, and multiple scattering events that direct more scattered radiation toward the detector [3].

- Refraction and Multiple Scattering: The grazing-incidence geometry introduces significant refraction effects that distort scattering patterns and require specialized correction approaches. Additionally, scattering can arise from both the direct and reflected beams, creating duplicated features in the detector image [3] [2].

The scattering pattern is typically described in terms of the scattering vector q, which has components both perpendicular (q₂) and parallel (q_y) to the sample surface, providing information about out-of-plane and in-plane structures, respectively [1] [5].

Experimental Geometry and Workflow

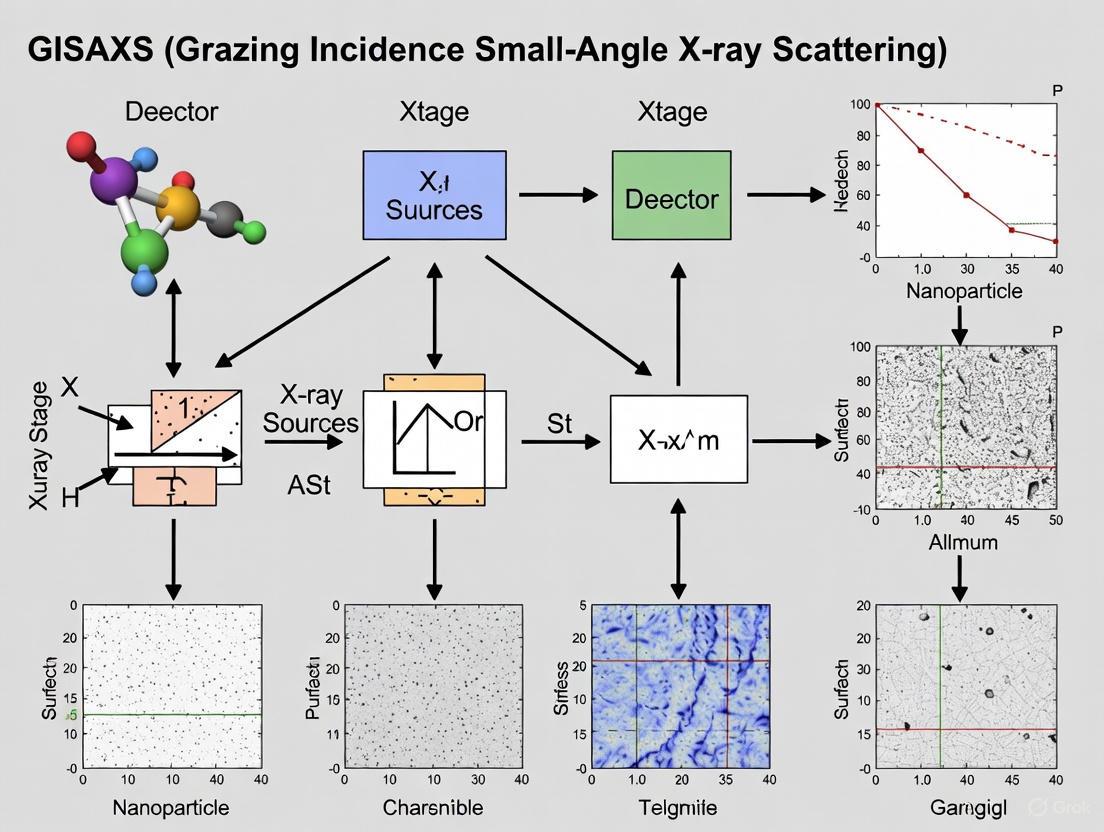

The GISAXS experimental configuration follows a standardized geometry optimized for surface sensitivity. The following diagram illustrates the key components and relationships in a typical GISAXS experiment:

The workflow begins with precise alignment of the sample to achieve the desired grazing incidence angle. The incident angle (αᵢ) is carefully controlled, typically using a sample-tilt stage, and set to values on the order of 0.05° to 0.50° [3]. This shallow angle ensures efficient reflection of the X-ray beam from the sample or substrate surfaces while maximizing surface sensitivity.

The scattered X-rays are collected using a two-dimensional area detector, such as a Pilatus 2M detector with a large detection area and high dynamic range [6]. The resulting 2D scattering pattern contains distinctive features—including peaks, rings, and diffuse scattering—that encode information about the nanoscale order in the sample. Careful analysis of these patterns enables quantification of structural parameters including average particle size, size distribution, shape, orientation, and long-period structures [4].

GISAXS for Nanoparticle Characterization

Application Principles and Capabilities

GISAXS has emerged as a powerful technique for nanoparticle characterization, particularly for investigating nanoparticles deposited on surfaces, quantum dot arrays, and metal nanoclusters. The method provides statistically robust information about nanoparticle systems under native or near-realistic conditions, enabling researchers to collect significant data on nanoparticle growth at the nanoscale, typically for structures up to approximately 100 nm in size [8].

A key advantage of GISAXS for nanoparticle research is its ability to probe excess electron density differences between nanoparticles and their surrounding medium [8]. This capability allows researchers to extract comprehensive structural information including:

- Size and Shape Distribution: GISAXS patterns reveal whether nanoparticles are spherical, elongated, or have more complex geometries based on characteristic scattering signatures.

- Spatial Arrangement: The technique can identify ordered arrays, random distributions, or anisotropic alignments of nanoparticles on surfaces.

- Orientation and Alignment: For nonspherical nanoparticles, GISAXS can determine preferential orientation relative to substrate features.

- Interparticle Distances: Regular spacing between nanoparticles creates distinctive interference patterns that can be quantified.

Case Study: Silver Nanoparticles on Ripple-Patterned Silicon

Recent research demonstrates the power of GISAXS for detailed nanoparticle characterization. A 2026 study investigated the sequential growth of silver nanoparticles (Ag-NPs) on ion-beam-induced nanorippled silicon substrates, combining GISAXS with GIWAXS (Grazing-Incidence Wide-Angle X-ray Scattering) and molecular dynamics simulations [8].

In this study, researchers fabricated ripple patterns on silicon substrates via ion beam irradiation, then deposited Ag-NPs under three different configurations: along the ion beam direction, opposite to it, and sequentially from both sides. GISAXS analysis revealed an inherent asymmetry in the ripple morphology, with slopes of approximately 6.4° and 6.9°, leading to slightly steeper facets on one side [8]. After Ag deposition, the lateral and vertical correlation lengths provided crucial information about nanoparticle size and distribution.

The research demonstrated that sequential deposition from both sides of the ripple effectively restricted elongation and promoted the formation of nearly spherical nanoparticles, in contrast to the ellipsoidal shapes obtained with single-direction deposition [8]. This controlled nanoparticle morphology is particularly valuable for Surface Enhanced Raman Scattering (SERS) applications, where the uniformity and density of plasmonic "hotspots" directly influence enhancement factors and signal reproducibility [8].

Experimental Protocol for Nanoparticle Characterization

Protocol: GISAXS Analysis of Nanoparticles on Patterned Substrates

1. Sample Preparation

- Substrate Patterning: Create ripple-patterned silicon substrates using Kaufman broad ion beam source under ultra-high vacuum conditions (base pressure: 1×10⁻⁷ mbar, working pressure: 2×10⁻⁴ mbar) at 700 eV energy with 2.5 mA ion current [8].

- Nanoparticle Deposition: Deposit metal nanoparticles (e.g., Ag, Au) using thermal evaporation or sputtering systems. For sequential growth studies, employ multiple deposition steps from different azimuthal angles relative to substrate features [8].

- Sample Cleaning: Ultrasonically clean substrates in acetone, distilled water, and isopropyl alcohol (5 minutes each) before processing [8].

2. GISAXS Data Collection

- Instrument Setup: Utilize synchrotron beamline (e.g., P03 beamline of PETRA III, DESY) or laboratory GISAXS system with appropriate X-ray energy (typically ~10 keV) [8] [6].

- Angle Alignment: Precisely align sample to achieve grazing incidence angle (typically 0.1°-0.3°), carefully controlling using sample-tilt stage [3].

- Data Acquisition: Collect 2D scattering patterns using large-area detector (e.g., Pilatus 2M). For in-situ studies, monitor structural evolution during deposition or annealing processes [8] [6].

3. Data Analysis

- Pattern Interpretation: Identify characteristic features in 2D scattering pattern (Yoneda peaks, Bragg rods, diffuse scattering) related to nanoparticle size, shape, and arrangement [1] [2].

- Quantitative Fitting: Apply Distorted-Wave Born Approximation (DWBA) theory to account for refraction effects and multiple scattering [2] [5].

- Parameter Extraction: Determine nanoparticle dimensions, size distributions, interparticle distances, and spatial correlations from fitting models [8] [4].

Research Toolkit for GISAXS Experiments

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for GISAXS

| Item | Function | Examples/Specifications |

|---|---|---|

| Synchrotron Beamline | High-intensity X-ray source | PETRA III (DESY), ALS SAXS/WAXS (BL 7.3.3) [8] [6] |

| Laboratory GISAXS System | Benchtop alternative to synchrotron | Systems with microfocus X-ray sources [1] |

| 2D X-ray Detector | Records scattering patterns | Pilatus 2M (172μm pixel size, 1475×1679 pixels) [6] |

| Goniometer Stage | Precise sample positioning | Multi-axis stage with angular resolution <0.001° [3] |

| Environmental Chamber | In-situ sample control | Hot stages (RT-200°C), solvent annealing, humidity control [6] |

| Analysis Software | Data processing and modeling | Igor Pro NIKA package, ATSAS, FIT2D [6] [9] |

Successful GISAXS experiments require careful selection of substrates and deposition methods tailored to the specific research objectives. For nanoparticle studies, common substrates include silicon wafers with native oxide layers, patterned substrates created by ion beam irradiation or lithography, and specialized templates designed to guide nanoparticle organization [8]. Deposition techniques range from thermal evaporation and sputtering for metal nanoparticles to spin-coating and dip-coating for polymer and colloidal systems.

Advanced in-situ capabilities significantly enhance the utility of GISAXS for studying dynamic processes. Modern beamlines offer specialized sample environments including hot stages for temperature-dependent studies, solvent annealing chambers for controlling thin film morphology, humidity control systems, and even slot die printers for studying deposition processes in real time [6]. These capabilities enable researchers to probe structural evolution under realistic processing conditions, providing invaluable insights into formation mechanisms and stability of nanostructured materials.

Complementary and Related Techniques

GISAXS is most powerful when combined with complementary characterization methods that provide additional structural information. The most commonly paired techniques include:

- GIWAXS (Grazing-Incidence Wide-Angle X-ray Scattering): While GISAXS probes nanoscale structures (1-100 nm), GIWAXS investigates atomic-level arrangements and crystalline structures through wide-angle scattering [1] [8]. The combination provides comprehensive structural information across multiple length scales.

- GIXD (Grazing-Incidence X-ray Diffraction): Used to characterize crystalline thin-film structures by analyzing Bragg reflections at higher scattering angles corresponding to atomic-level distances [1].

- GTSAXS (Grazing-incidence Transmission SAXS): A variant where the X-ray beam is directed toward the sample edge, reducing refraction-induced distortion and multiple scattering effects for cleaner data interpretation [7].

- Microscopy Techniques (AFM, SEM, TEM): While GISAXS provides statistical information over large areas, microscopy methods offer local, real-space imaging with high spatial resolution, creating a complementary analysis approach [1] [8].

The integration of these techniques within a single research framework enables comprehensive characterization of complex nanostructured materials, connecting local structural features with statistically representative average properties—a crucial capability for advancing nanomaterials science and applications.

Grazing-Incidence Small-Angle X-Ray Scattering (GISAXS) is a powerful, surface-sensitive technique for probing the nanostructure of thin films, coatings, and surfaces. The geometry of a GISAXS experiment is fundamentally a reflection-mode version of Small-Angle X-Ray Scattering (SAXS) [3]. Its unique power comes from the grazing-incidence geometry, which uses very small incident angles (typically on the order of 0.05° to 0.50°) to achieve a high scattering signal from ultra-thin layers and nanoscale objects on surfaces [3] [1]. This geometry makes GISAXS an indispensable tool for nanoparticle characterization, providing statistical information about particle size, shape, spatial arrangement, and order across a large sample area, thus complementing local probe techniques like Atomic Force Microscopy (AFM) or Transmission Electron Microscopy (TEM) [1] [10].

For research focused on nanoparticle characterization, understanding the essential geometry—specifically the control of the incident X-ray angle and the configuration of the 2D detector—is critical. It is this geometry that dictates the probe's surface sensitivity, enables a form of depth profiling, and ultimately determines how the measured scattering pattern relates to the sample's nanostructure [3] [11].

The Core Components of GISAXS Geometry

The GISAXS experiment is built upon a specific arrangement of its core components, each playing a vital role in data acquisition.

The Grazing-Incidence Angle (αi)

The most defining aspect of the GISAXS geometry is the shallow grazing-incidence angle (αi) at which the collimated X-ray beam strikes the sample surface. This angle is carefully controlled using a high-precision sample-tilt stage [3]. The choice of αi is not arbitrary; it is strategically selected relative to the critical angle (αc) of the sample material to control the X-ray penetration depth and, consequently, the experiment's sensitivity [11].

- Below the Critical Angle (αi < αc): The X-ray beam undergoes total external reflection. The beam probes only a few nanometers into the film due to the evanescent wave phenomenon, making the measurement exceptionally surface-sensitive [3].

- Above the Critical Angle (αi > αc): The beam penetrates deeply into the film and may be transmitted through it. In this regime, the scattering signal comes from the entire illuminated volume of the film, providing information about the "bulk" structure of the thin film [3].

By comparing measurements above and below the critical angle, researchers can perform a limited form of depth profiling, differentiating the nanostructure at the surface from the structure buried within the film [3].

The X-ray Beam and its Footprint

A direct consequence of the grazing-incidence geometry is the large beam footprint. A typically sized X-ray beam (e.g., 50 µm in height) impinging at a shallow angle of 0.1° will be projected into a long stripe on the sample surface, which can be several centimeters long [3] [12]. While this large footprint provides excellent statistical averaging and enhances scattering intensity, it has traditionally limited GISAXS to samples of millimeter size. However, advanced approaches using highly focused beams have demonstrated that GISAXS measurements on micrometre-sized targets are possible [12].

The 2D Detection System

The scattering from the sample is captured using a two-dimensional (2D) X-ray detector positioned perpendicular to the direct beam [3]. The recorded pattern is a complex intensity map that encodes information about the nanoscale order in the sample. The detector captures scattering over a range of exit angles:

- Out-of-plane angle (αf): The exit angle relative to the sample surface plane.

- In-plane angle (2θf): The azimuthal angle in the sample plane [11].

A beam stop is essential to block the intense specularly reflected beam and the direct beam spill-over, which would otherwise saturate and damage the detector [11].

The schematic below illustrates the core geometric setup and scattering pathways of a GISAXS experiment.

Quantitative Parameters of a GISAXS Experiment

The geometry of a GISAXS experiment is defined by specific quantitative parameters. The tables below summarize the key angular values and the resulting beam footprint calculations, which are critical for experimental planning.

Table 1: Key Angular Parameters in a GISAXS Experiment

| Parameter | Symbol | Typical Range | Function in the Experiment |

|---|---|---|---|

| Incidence Angle | αi | 0.05° to 0.50° [3] | Controls beam penetration depth and surface sensitivity. Selected relative to the material's critical angle. |

| Critical Angle | αc | ~0.1° to 0.5° (material-dependent) | The angle below which total external reflection occurs. Demarcates the surface-sensitive regime. |

| Out-of-plane Exit Angle | αf | Varies with detector position | Measured perpendicular to the sample surface. Sensitive to vertical (out-of-plane) structural features. |

| In-plane Exit Angle | 2θf | Varies with detector position | Measured parallel to the sample surface. Sensitive to lateral (in-plane) structural features and order. |

Table 2: Beam Footprint Calculations for Common Experimental Conditions

| Incident Beam Height | Incidence Angle (αi) | Beam Footprint Length | Experimental Implication |

|---|---|---|---|

| 50 µm | 0.1° | ~29 mm [3] | Provides a large illuminated volume for high signal intensity and good statistical sampling. Requires a large, uniform sample. |

| 500 µm | 0.5° | ~57 mm [12] | Standard for many synchrotron experiments. Offers a strong scattering signal from large sample areas. |

| ~300 nm | ~0.6° | ~30 µm [12] | Enables measurements on micrometre-sized targets. Presents significant technical challenges in sample alignment. |

Experimental Protocol: Setting Up a GISAXS Experiment

This protocol details the essential steps for configuring the geometry of a GISAXS experiment, with a focus on nanoparticle characterization.

Sample and Substrate Preparation

- Substrate Selection: Use a flat, smooth substrate (e.g., a silicon wafer with native oxide) that is larger than the expected X-ray beam footprint.

- Nanoparticle Deposition: Deposit the nanoparticle sample onto the substrate using a method appropriate for your research (e.g., spin-coating, drop-casting, Langmuir-Blodgett transfer, or in-situ growth) [2] [10]. The goal is to achieve a uniform layer or a well-defined pattern of nanoparticles.

Instrument Alignment and Angle Calibration

- Beam Definition: Use slits to define the size and divergence of the incident X-ray beam. A smaller vertical beam size can be used to reduce the footprint for small samples [12].

- Sample Alignment: Mount the sample on a high-precision goniometer. Align the sample surface to be coincident with the axis of the rotation stage. This is a critical step to ensure the accurate setting of the grazing-incidence angle.

- Angle of Incidence Calibration: Carefully calibrate the 0° position where the X-ray beam is parallel to the sample surface. The incident angle (αi) is then set by rotating the sample stage by a fraction of a degree from this position.

Data Collection Procedure

- Determine Critical Angles: If unknown, perform an X-ray reflectivity (XRR) measurement on your sample to determine the critical angles (αc) of the film and substrate [13].

- Select Incident Angle: Choose an αi based on your scientific question.

- For maximum surface sensitivity (probing the top ~few nm), set αi just below the critical angle of the film.

- To probe the entire film volume, set αi above the critical angle of the substrate [11].

- Configure Detector and Beamstop: Position the 2D detector perpendicular to the direct beam at a known sample-to-detector distance. Place a beam stop accurately to block the intense specular reflection and protect the detector [11].

- Acquire Scattering Pattern: Record the 2D scattering pattern with an appropriate exposure time. For kinetic studies, continuous or rapid sequential acquisition can be used to track structural changes in real-time [11].

The workflow below summarizes the key decision points and steps in this protocol.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

A successful GISAXS experiment relies on more than just the X-ray instrument. The table below lists key materials and their functions, particularly in the context of nanoparticle research.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for GISAXS

| Item | Function in the GISAXS Experiment |

|---|---|

| Flat, Polished Substrate (e.g., Silicon Wafer) | Provides a smooth, flat surface for sample deposition. Its well-defined critical angle and low roughness are essential for clean data interpretation [1]. |

| Nanoparticle Dispersion | The sample of interest, which must be prepared and deposited uniformly to avoid artifacts and ensure a representative scattering signal. |

| High-Precision Goniometer | A motorized stage that allows for precise control of the incident angle (αi) and other sample orientations, which is fundamental to the technique [3]. |

| 2D X-ray Detector (e.g., Pixel Array Detector) | Captures the scattered X-rays to form the 2D GISAXS pattern. Modern detectors enable fast data collection for real-time kinetic studies [11]. |

| Beamstop | A small, X-ray opaque shield that protects the detector from the intense direct and specularly reflected beams, which are many orders of magnitude brighter than the weak scattering signal [11]. |

| Analysis Software (e.g., BornAgain, GISAXSshop) | Specialized software is required to model the complex scattering patterns within the Distorted-Wave Born Approximation (DWBA) and extract quantitative structural parameters [14]. |

Data Analysis and Interpretation

The raw 2D GISAXS pattern is a distorted representation of the sample's reciprocal space due to refraction of the X-ray beam at the sample surface and multiple scattering events (e.g., scattering from both the direct and reflected beams) [15]. Interpreting these patterns requires an understanding of these effects.

- The Distorted-Wave Born Approximation (DWBA): This is the primary theoretical framework used to model and fit GISAXS data. The DWBA accounts for refraction and multiple scattering, allowing researchers to relate the distorted detector image to the sample's true nanostructure [2] [15].

- Unwarping GISAXS Data: Computational methods have been developed to "unwarp" GISAXS data, reconstructing an estimate of the undistorted reciprocal-space scattering. This can make the data easier to interpret and allow for the use of analysis tools developed for transmission SAXS [15].

- Signature Patterns for Nanoparticles:

- Disordered Nanoparticles: Produce a circular or elliptical ring pattern, where the radius is related to the average particle size via the form factor.

- Ordered Nanoparticle Arrays: Produce distinct Bragg peaks, the positions of which reveal the symmetry and lattice spacing of the superlattice [1] [2].

In conclusion, the essential geometry of a GISAXS experiment, centered on the precise control of the grazing-incidence angle and the detection of the scattered radiation, is the foundation of its power as a characterization tool. A deep understanding of how the incidence angle, beam footprint, and detector signal interrelate is paramount for designing effective experiments, particularly in the field of nanoparticle research, where it provides unparalleled statistical insights into nanoscale structure and order.

Grazing-Incidence Small-Angle X-Ray Scattering (GISAXS) has emerged as a powerful technique for characterizing nanostructured thin films and surfaces, with particular relevance for nanoparticle research. Originally introduced in 1989, this method combines features from small-angle X-ray scattering and diffuse X-ray reflectivity, enabling the analysis of density correlations and nanostructured object shapes at surfaces or buried interfaces [1]. For researchers investigating nanoparticle self-assembly, catalytic nanoparticles, and polymer thin films, GISAXS provides unique advantages that address fundamental limitations of traditional characterization methods. The technique analyzes scattering data at small scattering angles, typically up to 5° 2θ, providing detailed structural information about nanoscale features [1]. This application note examines three core advantages of GISAXS—representative sampling, minimal sample preparation, and environmental flexibility—within the context of nanoparticle characterization for advanced materials and drug development research.

Core Advantages of GISAXS

Representative Sampling

Unlike localized characterization techniques that provide information from limited sample areas, GISAXS delivers statistically representative data from large sample areas, enabling robust quantitative analysis of nanoparticle systems.

- Large Area Interrogation: GISAXS probes the entire illuminated near-surface volume, with the beam footprint typically extending to several millimeters on the sample surface [16] [17]. This extensive coverage ensures that the collected data represents the overall sample characteristics rather than localized features.

- Statistical Significance: The technique provides averaged results that are representative of a large sample area, overcoming the limitation of local probe techniques that may miss important structural variations or defects [1]. This is particularly valuable for quality control in nanoparticle thin film manufacturing and for ensuring experimental reproducibility.

- Comparative Advantage Over Local Techniques: Classical nanoscale structural methods like Atomic Force Microscopy (AFM) and Transmission Electron Microscopy (TEM) provide highly precise local information about the nanostructured surface but struggle to deliver representative averaged results from a sample [1]. GISAXS ideally complements these microscopic methods by providing the statistical overview needed for comprehensive characterization.

Minimal Sample Preparation

GISAXS requires minimal sample preparation compared to many analytical techniques, reducing artifacts and streamlining the characterization workflow for nanoparticle systems.

- Direct Measurement Capability: Nanoparticle dispersions can often be measured directly on suitable substrates without complex processing. Self-assembly processes can be studied in situ at liquid subphases without requiring fixation or drying [18] [16].

- Reduced Introduction of Artifacts: The minimal preparation requirements significantly reduce the risk of introducing artifacts that might alter the native nanostructure. This is particularly important for studying delicate self-assembling systems, soft matter, and biological nanomaterials where processing steps could disrupt the natural organization.

- Complementary to Intensive Preparation Methods: Techniques like TEM often require extensive sample preparation including thinning, staining, or sectioning, which can modify the original nanostructure. GISAXS provides an alternative view with minimal intervention, preserving the native state of nanoparticle assemblies [1].

Environmental Flexibility

GISAXS studies can be performed under diverse environmental conditions, enabling in situ and operando studies of nanoparticles under realistic processing or application conditions.

- Controlled Atmosphere and Temperature: GISAXS can be performed in vacuum or under controlled atmosphere at ambient or non-ambient temperature [1]. This flexibility allows researchers to simulate real-world application environments or specific processing conditions.

- In Situ and Operando Capabilities: The technique enables real-time monitoring of dynamic processes such as nanoparticle self-assembly [18], thermal treatments, or response to environmental stimuli. This temporal resolution provides insights into kinetic processes and structural evolution.

- Penetration Depth Control: By varying the incident angle from 0.8αi to a factor of 3–4 of αc of the material, researchers can selectively calculate the beam penetration depth from several nanometers to several micrometers, respectively [16]. This allows depth-profiling experiments to investigate buried interfaces or gradient structures in nanoparticle composites.

Table 1: Quantitative Comparison of GISAXS Advantages in Practice

| Advantage | Technical Basis | Experimental Impact | Typical Parameters |

|---|---|---|---|

| Representative Sampling | Large beam footprint (up to ~11 mm) illuminating extensive sample area [16] [17] | Provides statistical average from ~mm² area vs. µm² for local techniques | Sample area probed: ~1-100 mm² [17] |

| Minimal Preparation | Non-destructive measurement requiring no sectioning, staining, or coating | Reduces preparation time from hours/days to minutes; minimizes artifacts | Measurement ready: Often <30 minutes |

| Environmental Flexibility | Compatible with various sample environments (vacuum, gas flow, liquid cells) | Enables in situ studies under realistic conditions | Temperature range: Cryogenic to >1000°C; Various atmospheres [1] |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: GISAXS Analysis of Nanoparticle Self-Assembly at Liquid Subphases

This protocol describes the methodology for studying nanoparticle self-assembly at liquid interfaces using a vertical geometry GISAXS setup, based on research conducted at the P10 beamline at PETRA III (DESY, Hamburg) [18].

Materials and Equipment

- Synchrotron Beamline: Configured for SAXS/GISAXS with vertical geometry

- Langmuir Trough: For containing liquid subphase and controlling surface pressure

- 2D X-ray Detector: Pilatus or similar single-photon-counting detector

- Gold Nanoparticles: Spherical nanoparticles (e.g., 10-100 nm diameter) in colloidal dispersion

- Optical Microscope: Integrated for measurement position verification

Procedure

Sample Preparation:

- Prepare nanoparticle colloidal dispersion at appropriate concentration (typically 0.1-5 mg/mL).

- Carefully spread nanoparticle dispersion onto the liquid subphase (typically water) in the Langmuir trough.

- Allow nanoparticles to self-assemble at the air/liquid interface, optionally controlling surface pressure with movable barriers.

Beamline Alignment:

- Align the vertical GISAXS setup to ensure precise grazing incidence on the liquid surface.

- Set incident angle αi typically below 1° to achieve total external reflection conditions.

- Calibrate sample-to-detector distance using standard reference materials (e.g., silver behenate).

Data Collection:

- Position the X-ray beam to graze the liquid surface where nanoparticles are assembling.

- Acquire 2D scattering patterns with appropriate exposure time (typically 0.1-10 seconds).

- Integrate optical microscopy to observe measurement position and formation of supercrystal flakes during data collection.

- Collect series of images to monitor temporal evolution of self-assembly process.

Data Analysis:

- Convert 2D detector images to reciprocal space (q-space) coordinates.

- Extract linecuts along in-plane (qy) and out-of-plane (qz) directions for quantitative analysis.

- Analyze peak positions to determine interparticle distances and lattice parameters.

- Model scattering patterns to extract information about nanoparticle ordering, film thickness, and density.

Protocol 2: In Situ GISAXS-CT for Spatial Mapping of Nanostructures

This protocol outlines the procedure for GISAXS coupled with computed tomography (CT) to visualize spatial distribution of nanostructures in thin films, based on methodologies developed at the BL03XU beamline at SPring-8 [17].

Materials and Equipment

- High-Brilliance X-ray Source: Synchrotron beamline with high flux (≥10¹² photons/s) and low divergence

- Precision Goniometer: For accurate sample positioning and rotation

- 2D X-ray Detector: Pilatus 1M or similar with high dynamic range

- Thin Film Samples: Nanoparticle layers on substrates (e.g., Au-patterned layers on silicon)

- Computational Resources: For tomographic reconstruction and data processing

Procedure

Sample Preparation:

- Fabricate nanoparticle layers on appropriate substrates (e.g., silicon wafers).

- For patterned samples, use masks or templates to create defined regions of nanoparticle assemblies.

- Mount sample securely on goniometer ensuring precise alignment of rotation axis.

Experimental Setup:

- Set X-ray wavelength to appropriate value (typically λ = 0.1 nm for high-energy measurements).

- Define sample-to-detector distance based on required q-range (e.g., 2275 mm for specific resolution).

- Adjust incident angle to critical angle regime (typically 0.2-0.5° for metal nanoparticles on silicon).

Data Acquisition:

- Perform translational scans along direction perpendicular to X-ray beam (Y direction) with step size comparable to beam size (typically 15-20 μm).

- At each Y position, acquire 2D GISAXS pattern with sufficient counting statistics (exposure time ~1 second).

- Rotate sample by defined angular increment (1-3°) and repeat translational scan.

- Continue until 180° rotation is completed, acquiring thousands of individual scattering patterns.

Tomographic Reconstruction:

- Extract scattering intensities at specific q-positions from all 2D patterns to create sinograms.

- Apply Total Variation (TV) regularization to minimize noise and artifacts in sinograms.

- Reconstruct CT images using filtered back-projection or advanced iterative algorithms.

- Generate spatial maps of nanostructural parameters (size, shape, ordering) across the sample.

Table 2: Key Parameters for GISAXS Experiments

| Parameter | Protocol 1: Liquid Subphases | Protocol 2: GISAXS-CT |

|---|---|---|

| X-ray Energy | Typically 10-15 keV [18] | 12.4 keV (λ = 0.1 nm) [17] |

| Incidence Angle (αi) | Below 1° [18] | 0.50° [17] |

| Sample-Detector Distance | Instrument dependent | 2275 mm [17] |

| Beam Size | Varies by beamline | 28.5 μm (H) × 99.5 μm (V) [17] |

| Exposure Time | 0.1-10 seconds per pattern | 1.0 second per pattern [17] |

| Spatial Resolution | μm range for volume sampling [18] | 15-20 μm translational steps [17] |

Experimental Design and Workflow

The experimental workflow for GISAXS investigation of nanoparticle systems involves careful planning and execution across multiple stages, from sample preparation to data analysis. The following diagram illustrates the complete process for a typical GISAXS study:

The decision path for selecting appropriate GISAXS measurement strategies depends on sample characteristics and research objectives. The following workflow guides researchers through key decision points:

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for GISAXS Experiments

| Item | Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Synchrotron Beam Access | High-brilliance X-ray source | Provides necessary flux and coherence for GISAXS measurements; essential for time-resolved studies [18] [16] |

| 2D X-ray Detector | Records scattering patterns | Single-photon-counting detectors (e.g., Pilatus, Eiger) with high dynamic range and low noise [17] [19] |

| Goniometer | Precise sample positioning | Allows control of incident angle and sample orientation with sub-micron precision [17] |

| Langmuir Trough | Controls liquid interfaces | Enables study of nanoparticle self-assembly at air/liquid interfaces with controlled surface pressure [16] |

| Standard Reference Materials | Calibration samples | Silver behenate or similar standards for q-range calibration [19] |

| Igor Pro with FitGISAXS | Data analysis software | Commercial software package for modeling and fitting GISAXS patterns [14] [19] |

| BornAgain | Scattering simulation software | Open-source package for simulating GISAXS patterns using Distorted Wave Born Approximation [14] |

GISAXS represents a powerful characterization platform for nanoparticle research, offering three distinct advantages that address critical challenges in nanomaterials science. The combination of representative sampling, minimal preparation requirements, and environmental flexibility makes GISAXS particularly valuable for investigating nanoparticle self-assembly processes, thin film morphology, and structural evolution under realistic conditions. As demonstrated in the protocols presented, this technique can be applied to diverse systems ranging from nanoparticle monolayers at liquid interfaces to complex patterned thin films. The continued development of GISAXS methodologies, including coupling with computed tomography and advanced reconstruction algorithms, promises to further enhance its capabilities for spatially-resolved nanostructural characterization. For researchers in drug development and nanomaterials science, GISAXS provides unique insights that complement local probe techniques and contribute to a more comprehensive understanding of nanoparticle systems.

Grazing-Incidence Small-Angle X-ray Scattering (GISAXS) is an advanced surface-sensitive technique widely used for analyzing the state and size distribution of nanoparticles in thin films, as well as nanoscale surface and interface structures [4]. A fundamental principle underlying its surface sensitivity is the controlled penetration of the X-ray beam into the sample, which is predominantly governed by the angle at which the X-ray beam strikes the sample surface. By varying the incident angle (αi) relative to the critical angle (αc) of the film or substrate material, researchers can selectively probe different depths within the near-surface region [16]. This controlled penetration is crucial for non-destructively depth-profiling nanostructured materials, enabling the study of buried interfaces, vertical compositional gradients, and the three-dimensional distribution of nanoparticles in thin films—a capability of significant interest for applications in drug delivery systems, organic photovoltaics, and advanced nanoelectronics.

Theoretical Foundation

The Critical Angle and Total External Reflection

The interaction of X-rays with matter at grazing incidence is described by the complex refractive index, ( n ), which is slightly less than 1 for X-rays and is expressed as ( n = 1 - δ + iβ ) [16]. The real part, ( δ ), governs refraction and scattering, while the imaginary part, ( β ), relates to absorption. The critical angle, ( αc ), is a material-dependent property below which total external reflection occurs. At incident angles smaller than ( αc ), the X-ray beam does not penetrate into the bulk material but instead propagates as an evanescent wave along the surface, exponentially decaying in intensity with depth. This phenomenon confines the scattering signal exclusively to the surface and immediate subsurface region, providing exceptional surface sensitivity.

Penetration Depth and Incident Angle Relationship

When the incident angle exceeds the critical angle, the beam begins to penetrate substantially into the material. The penetration depth, ( Λ ), defined as the depth at which the X-ray intensity falls to ( 1/e ) of its surface value, becomes a strong function of ( αi ). As detailed in recent synchrotron studies, by varying the angle of incidence from approximately ( 0.8αc ) to 3–4 times ( α_c ), the researcher can selectively control the beam penetration depth from several nanometres to several micrometres, respectively [16]. This tunability allows GISAXS to interrogate specific depth regions within a sample by simply adjusting a single geometric parameter.

Table 1: Penetration Depth Regimes in GISAXS

| Incident Angle Regime | Penetration Behavior | Primary Information Obtained |

|---|---|---|

| ( αi < αc ) (Below Critical) | Evanescent wave; minimal penetration (nanometers) | Surface structure, top-layer nanoparticles |

| ( αi ≈ αc ) (Near Critical) | Penetration increases sharply; depth is tunable | Interface morphology, near-surface ordering |

| ( αi > αc ) (Above Critical) | Significant penetration into the bulk (micrometers) | Buried interfaces, vertical particle distribution, film homogeneity |

Quantitative Penetration Depth Data

The precise relationship between the incident angle and the penetration depth is quantifiable. The following table provides characteristic penetration depths for a silicon substrate and a polymeric thin film, calculated for a representative X-ray energy of 10 keV. These values illustrate the powerful depth-profiling capability achievable through incident angle variation.

Table 2: Penetration Depth vs. Incident Angle for a Silicon Substrate (10 keV X-rays, ( α_c ) ≈ 0.18°)

| Incident Angle (α_i) | Relation to α_c | Approximate Penetration Depth | Probed Region |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0.14° | ~0.8 × α_c | ~5 nm | Extreme surface, 2D monolayers |

| 0.18° | = α_c | ~10 nm | Surface & substrate interface |

| 0.36° | 2 × α_c | ~100 nm | Thin film, near-surface nanostructures |

| 0.54° | 3 × α_c | ~1000 nm (1 µm) | Bulk of thin film, buried layers |

Table 3: Penetration Depth vs. Incident Angle for a Polymeric Thin Film (10 keV X-rays, ( α_c ) ≈ 0.15°)

| Incident Angle (α_i) | Relation to α_c | Approximate Penetration Depth | Probed Region |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0.12° | 0.8 × α_c | ~4 nm | Polymer surface, top nanoparticle layer |

| 0.15° | = α_c | ~7 nm | Surface and polymer-substrate interface |

| 0.30° | 2 × α_c | ~70 nm | Bulk of polymer film, particle dispersion |

| 0.45° | 3 × α_c | ~700 nm | Entire film thickness, vertical gradients |

Experimental Protocols for Depth Profiling

Protocol: GISAXS Depth Profiling via Incident Angle Series

Objective: To determine the vertical distribution of nanoparticles within a polymer thin film on a silicon substrate.

Materials & Reagents:

- Sample: Thin film with incorporated nanoparticles on a silicon wafer.

- X-ray Source: Synchrotron beamline providing a monochromatic, collimated X-ray beam (e.g., 10 keV).

- Goniometer: High-precision multi-axis stage capable of milli-degree angular resolution.

- 2D Detector: Large-area, high dynamic range detector (e.g., Pilatus series) placed at a sufficient distance (1-5 m) to achieve desired q-resolution [20].

Procedure:

- Sample Alignment: Mount the sample on the goniometer. Use the direct beam to locate the sample edge and then carefully align the sample surface to be parallel to the beam path (i.e., find ( α_i = 0° )).

Critical Angle Determination: Perform an X-ray reflectivity (XRR) scan by measuring the specularly reflected beam intensity while rocking the incident angle ( αi ) through a small angular range (e.g., 0° to 0.5°). The critical angle ( αc ) is identified as the angle where the intensity drops precipitously.

GISAXS Measurement Series:

- Set the incident angle to the first value in your series (e.g., ( 0.8α_c )).

- Acquire a 2D GISAXS pattern with an adequate exposure time for a good signal-to-noise ratio.

- Increment the incident angle to the next value in the series (e.g., ( αc ), ( 1.5αc ), ( 2αc ), ( 3αc )).

- Repeat the acquisition at each angle, ensuring all other geometric parameters (beam position, detector distance) remain constant.

Data Reduction: For each 2D image, perform data reduction to extract 1D scattering profiles. This may involve sector or line cuts to isolate in-plane (e.g., horizontal line cut at ( qz = 0.03 Å^{-1} )) and out-of-plane (e.g., vertical line cut at ( qy \sim 0.012 Å^{-1} )) structural information [20].

Data Analysis and Interpretation

- Analysis of Angle Series: Compare the 1D scattering profiles obtained at different incident angles. The appearance, intensification, or shift of scattering features (peaks, shoulders) as a function of ( α_i ) indicates the depth origin of the corresponding nanostructures.

- Modeling with DWBA: Quantitative analysis requires modeling the data using the Distorted Wave Born Approximation (DWBA), which correctly accounts for the reflection and refraction effects at grazing angles [21]. Software packages like BornAgain [14] or IsGISAXS can be used to fit the data from multiple angles simultaneously with a structural model that includes the vertical distribution of nanoparticles.

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 4: Essential Research Reagent Solutions and Materials for GISAXS Depth Profiling

| Item | Function/Application | Example/Note |

|---|---|---|

| Silicon Wafer Substrate | A common, flat, low-roughness substrate for thin film deposition. | Provides a well-defined critical angle (~0.18° at 10 keV). |

| Langmuir-Blodgett Trough | To prepare highly ordered nanoparticle monolayers at air/liquid interfaces for model studies [16]. | Used for fundamental studies of self-assembly. |

| Precision Goniometer | To accurately align the sample and set the incident angle with milli-degree precision. | Essential for reliable penetration depth control. |

| 2D X-ray Detector | To capture the scattered intensity pattern. | Pilatus or Eiger detectors are common choices [20]. |

| BornAgain Software | For modeling and fitting GISAXS data using the Distorted Wave Born Approximation (DWBA) [14]. | Open-source, allows modeling of complex nanostructures. |

| IsGISAXS Software | For simulating 2D GISAXS patterns based on the DWBA [14]. | Useful for predicting scattering from proposed models. |

Workflow Visualization

Diagram 1: GISAXS depth profiling workflow.

Diagram 2: Incident angle controls penetration depth.

Advanced Applications and Recent Developments

The principle of penetration depth control is being leveraged in advanced GISAXS applications. The development of Grazing-incidence Transmission SAXS (GTSAXS), where the beam is directed at the sample's edge, provides cleaner sub-horizon scattering data with less distortion, useful for probing structures near the substrate interface [7]. Furthermore, the integration of coherent imaging techniques like ptychography with grazing incidence geometry is a frontier in research. This approach replaces the conventional DWBA with a multislice wave-propagation model, enabling the full 3D reconstruction of complex surface and near-surface nanostructures from coherent diffraction data, starting from a random initial guess [21]. These advanced methods promise even more detailed and quantitative depth-resolved structural analysis for future nanoparticle research.

Grazing-incidence X-ray scattering techniques have become indispensable tools for the nanoscale characterization of thin films and surfaces, particularly in the field of nanoparticle research. These techniques, which include Grazing-Incidence Small-Angle X-Ray Scattering (GISAXS), Grazing-Incidence Wide-Angle X-Ray Scattering (GIWAXS), and Grazing-Incidence X-Ray Diffraction (GIXD), enable non-destructive probing of structures across multiple length scales—from mesoscopic ordering down to atomic arrangements [22]. For researchers focused on nanoparticle characterization, understanding the complementary information provided by these methods is crucial for developing comprehensive structure-property relationships. The fundamental principle shared by all these techniques involves directing an X-ray beam at a very shallow incident angle (typically less than 1°) onto a sample surface, which significantly enhances the interaction volume with thin films while minimizing background scattering from the substrate [4] [1]. This approach allows for the collection of statistically significant data from large surface areas, providing averaged results that are representative of the entire sample—a distinct advantage over local probe techniques like atomic force microscopy or transmission electron microscopy [1].

Technical Foundations and Comparative Analysis

Core Principles and Length Scales

The family of grazing-incidence techniques probes different structural hierarchies within nanomaterials by measuring X-rays scattered at different angular ranges. GISAXS analyzes scattering at small angles (typically up to a few degrees) to investigate nanoscale density fluctuations and electron density variations, providing information about particle size, shape, and arrangement in the mesoscopic size range from approximately 1 nm to 100 nm [4] [23]. In contrast, GIWAXS collects scattering data at wider angles (typically up to 45°) to characterize molecular and atomic-level structures, including crystalline phases, molecular packing, and orientation in thin films [1] [22]. GIXD shares similarities with GIWAXS but traditionally implies the use of a point or line detector with collimation in a diffractometer setup, and is often applied to materials with sharp diffraction peaks [23]. The combination of these techniques allows researchers to correlate nanostructural organization with molecular ordering, which is particularly valuable for understanding how nanoparticle synthesis parameters influence final material properties.

Table 1: Key Characteristics of Grazing-Incidence X-ray Techniques

| Technique | Probed Length Scales | Primary Information | Typical Samples |

|---|---|---|---|

| GISAXS | ~1 nm to 100 nm [23] | Particle size, shape, distribution, mesoscale ordering, pore structure [4] | Nanoparticle arrays, block copolymer films, porous materials [1] |

| GIWAXS | Atomic to ~2 nm [23] | Crystalline structure, molecular packing, crystal orientation, polymorphism [22] [24] | Organic semiconductors, perovskite films, crystalline nanoparticles [8] [24] |

| GIXD | Atomic to ~2 nm [23] | Crystal structure, lattice parameters, epitaxial relationships [23] | Highly crystalline thin films, quantum dots, 2D materials |

Complementary Information for Nanoparticle Characterization

The particular strength of combining GISAXS with GIWAXS or GIXD lies in their ability to provide complementary structural information across multiple hierarchical levels in a single experiment. For nanoparticle research, this multi-scale approach enables researchers to connect synthesis parameters with resulting functional properties. GISAXS efficiently probes the size, shape, and spatial distribution of nanoparticles on surfaces or within thin films, including parameters such as average particle size, size distribution, and long-period structures [4]. Simultaneously, GIWAXS provides insights into the crystalline structure, phase composition, and molecular orientation within the same nanoparticles [8]. This combination is particularly powerful for investigating structure-property relationships in functional nanomaterials, such as plasmonic nanoparticles for sensing applications, catalytic nanoparticles, or semiconductor quantum dots for optoelectronic devices.

A research example demonstrating this complementary approach investigated the sequential growth of silver nanoparticles (Ag-NPs) on ripple-patterned silicon substrates [8]. In this study, GISAXS revealed the morphology and ordering of Ag-NPs, showing how deposition geometry affected nanoparticle shape and spatial distribution. The analysis quantified inherent asymmetry in the ripple morphology, with slopes of approximately 6.4° and 6.9°, and revealed how sequential deposition from both sides of the ripple promoted the formation of truncated spherical nanoparticles rather than elongated structures. Concurrently, GIWAXS provided information about the crystalline structure and atomic arrangements within the nanoparticles, showing that the sequential deposition method reduced the crystalline size ratio (D⊥/D‖), indicating more isotropic crystallite development [8]. This combined analysis provided unprecedented insights into the atomic-scale reorganization of Ag-NPs on nanostructured surfaces, demonstrating how coordinated GISAXS/GIWAXS experiments can elucidate fundamental growth mechanisms.

Experimental Protocols

Integrated GISAXS/GIWAXS Measurement Protocol

The following protocol describes a standardized approach for simultaneous GISAXS and GIWAXS data collection, particularly relevant for in-situ studies of nanoparticle growth and self-assembly processes.

Sample Preparation

- Substrate Selection: Use atomically smooth substrates (e.g., silicon wafers with native oxide layer, glass slides) appropriate for your nanoparticle system. Clean substrates ultrasonically in acetone, distilled water, and isopropyl alcohol for 5 minutes each to ensure surface cleanliness [8].

- Nanoparticle Deposition: Deposit nanoparticles using your method of choice (spin-coating, drop-casting, Langmuir-Blodgett transfer, or in-situ deposition). For sequential deposition studies like the Ag-NP example, control the deposition geometry relative to substrate features [8].

- Sample Mounting: Secure samples on a multi-axis goniometer capable of precise translational and rotational positioning. Ensure the sample surface is aligned perpendicular to the rotation axis with high accuracy (≤0.002°) [24].

Instrument Setup and Alignment

- X-ray Source: Utilize a synchrotron beamline or laboratory X-ray source with sufficient flux. For combined GISAXS/GIWAXS, hard X-rays (typically 10-15 keV) are preferred for their higher penetration and broader q-range coverage [22] [24].

- Beam Definition: Employ appropriate slits or focusing optics to define the beam size (e.g., 0.2 mm horizontal × 0.05 mm vertical) [24].

- Detector Configuration: Position two 2D detectors simultaneously—one at a longer distance (1-5 m) for GISAXS and one at a shorter distance (0.1-0.3 m) for GIWAXS. Ensure detectors have appropriate pixel sizes and dynamic ranges for the expected scattering intensities.

- Incidence Angle Optimization: Align the sample surface to the X-ray beam using the goniometer. Set the grazing-incidence angle (αi) near the critical angle of the sample (typically 0.1-0.5°) to enhance surface sensitivity while ensuring sufficient penetration depth [1] [22].

Data Collection

- Footprint Calculation: Verify that the X-ray footprint (determined by beam size divided by sin(αi)) completely covers the region of interest on the sample.

- GISAXS Acquisition: Collect 2D scattering patterns with the SAXS detector using exposure times ranging from 0.1-10 seconds, depending on source brightness and sample scattering power.

- GIWAXS Acquisition: Simultaneously collect wide-angle patterns with the second detector. Adjust exposure times to prevent detector saturation while maintaining adequate signal-to-noise.

- Angular Scanning: For comprehensive structural analysis, perform azimuthal rotations (ϕ) over 180° or 360° with step sizes of 0.1-0.5° [24]. For in-situ studies, collect time-series data during nanoparticle growth or processing.

Data Analysis Workflow

The analysis of combined GISAXS/GIWAXS data involves both qualitative interpretation of scattering patterns and quantitative modeling of the underlying nanostructure.

Data Reduction: Apply necessary corrections to the 2D scattering patterns, including background subtraction, geometric corrections, and solid-angle normalization.

GISAXS Analysis:

- Identify characteristic features in the 2D pattern: intensity streaks indicate ordered lamellar structures; correlation peaks suggest periodic arrangements; rings or partial rings indicate disordered or polycrystalline structures [1].

- Extract 1D line profiles along specific directions (in-plane qy, out-of-plane qz) for quantitative analysis.

- Model the data using form factor (particle shape/size) and structure factor (interparticle correlations) models to determine nanoparticle morphology and spatial organization.

GIWAXS Analysis:

- Identify Bragg peaks and determine crystal structure and lattice parameters through peak indexing [24].

- Analyze azimuthal intensity distributions to determine crystallite orientation relative to the substrate.

- Calculate crystallite size using Scherrer analysis of peak broadening.

Correlative Interpretation: Integrate information from both techniques to build a comprehensive structural model that connects nanoscale organization with atomic-level crystal structure.

Figure 1: Experimental workflow for combined GISAXS/GIWAXS measurements.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 2: Essential Materials for GISAXS/GIWAXS Experiments on Nanoparticles

| Category | Specific Items | Function & Importance |

|---|---|---|

| Substrates | Silicon wafers (with native oxide), Glass slides, PMMA-coated Si [8] [24] | Provide flat, well-defined surfaces for nanoparticle deposition; silicon wafers are ideal due to their atomic smoothness and well-characterized properties. |

| Cleaning Reagents | Acetone, Deionized water, Isopropyl alcohol [8] | Remove organic and particulate contamination from substrates through ultrasonic cleaning, ensuring reproducible nanoparticle deposition. |

| Nanoparticle Synthesis | Metal precursors (e.g., AgNO3), Reducing agents, Surfactants, Solvents | Control nanoparticle size, shape, and surface functionalization during synthesis; critical for tailoring nanostructural properties. |

| Deposition Tools | Spin coater, Thermal evaporator, Langmuir-Blodgett trough | Create uniform nanoparticle films with controlled thickness and organization on substrates. |

| Calibration Standards | Silver behenate, Glassy carbon, Lupolen [22] | Calibrate detector distances, angular ranges, and intensity responses; essential for quantitative comparisons between experiments. |

| Alignment Aids | Laser pointers, Optical microscopes, Fluorescent screens | Facilitate precise sample alignment relative to the X-ray beam, critical for grazing-incidence geometry. |

Advanced Applications and Future Directions

The combination of GISAXS, GIWAXS, and GIXD continues to evolve with instrumental advancements, enabling increasingly sophisticated nanoparticle characterization. In-situ and operando studies represent a particularly powerful application, where structural evolution is monitored in real-time during nanoparticle synthesis, processing, or device operation [22]. For example, researchers can observe morphological and crystalline changes during thermal annealing, solvent vapor exposure, or electrical biasing, directly connecting processing parameters with structural outcomes. Recent instrumental progress has enabled data acquisition times down to milliseconds, opening possibilities for studying dynamic processes in nanoparticle systems with unprecedented temporal resolution [22].

Emerging variations of these techniques further expand their applicability to complex nanoparticle systems. Micro- and nanofocused GISAXS/GIWAXS utilize X-ray beams focused to micron or sub-micron dimensions to perform spatial mapping of structural heterogeneity across nanoparticle assemblies [22]. This approach is particularly valuable for investigating domain boundaries, gradient structures, or localized processing effects in nanoparticle films. Grazing-incidence diffraction tomography represents another innovative development, combining GIWAXS with computed tomography principles to quantitatively determine the dimension and orientation of crystalline domains in thin films without restrictions on substrate type or film thickness [24]. This method utilizes the fact that peaks from a single crystal only appear on the detector when the reciprocal lattice intersects with the Ewald sphere, allowing reconstruction of domain shapes and absolute orientations through rotational scanning.

The ongoing development of analysis software and computational tools is making these techniques more accessible to non-specialists while enhancing the sophistication of quantitative analysis. Specialized software packages, such as indexGIXS for interactive indexing of grazing-incidence scattering data, are addressing the computational challenges associated with analyzing complex fiber texture scattering patterns from organic thin films and nanoparticle assemblies [25]. These computational advances, combined with the versatile experimental framework provided by GISAXS, GIWAXS, and GIXD, ensure that grazing-incidence scattering techniques will remain at the forefront of nanomaterial characterization for the foreseeable future.

Grazing-Incidence Small-Angle X-ray Scattering (GISAXS) is a powerful, non-destructive technique for investigating the nanostructure of thin films and surfaces. Originally introduced in 1989, it has become a fundamental tool for characterizing a wide range of materials, from porous materials and metals to polymers and biological soft matter [1]. Its key advantage lies in its ability to provide statistically representative, averaged structural information over a large sample area, effectively complementing local probe techniques like Atomic Force Microscopy (AFM) and Transmission Electron Microscopy (TEM) [1]. This application note details the interpretation of basic GISAXS patterns within the context of nanoparticle characterization research.

The geometry of a GISAXS experiment involves a highly collimated X-ray beam striking the sample surface at a very small grazing incidence angle (αi, typically below 1°). This configuration limits the penetration depth of the X-rays, minimizing background scattering from the substrate. The scattered X-rays at small angles are captured by a two-dimensional detector, producing a pattern that contains information about the in-plane (qy) and out-of-plane (qz) nanostructure [1]. The following workflow diagram outlines the core process of a GISAXS experiment and its connection to a specific nanoparticle study.

Fundamental GISAXS Pattern Interpretation

The two-dimensional GISAXS pattern is a direct consequence of the size, shape, and arrangement of nanoscale objects on the surface. Interpreting these patterns allows researchers to discern the underlying structure of the sample.

Pattern Features and Their Structural Meaning

- Yoneda Band: A highly intense, horizontal band across the detector. Its position is sensitive to the material properties of the sample and substrate and is crucial for qualitative analysis.

- Specular Peak: Located on the detector's meridian (qz-axis, where qy=0), this peak results from direct reflection of the incident beam. Its intensity and shape provide information about surface roughness and layer thickness.

- Bragg Peaks / Correlation Peaks: Distinct, sharp spots or rods indicate a highly ordered, periodic structure. Their positions are inversely related to the repeat distances in the nanostructure.

- Diffuse Scattering: A broad, halo-like intensity distribution signifies disordered or weakly correlated structures with a distribution of particle sizes and distances.

Pattern Archetypes and Material Morphology

The following diagram illustrates how different sample morphologies produce distinct, characteristic GISAXS signatures.

Experimental Protocol: Nanoparticle Growth on Patterned Surfaces

This protocol details a specific experiment investigating the growth of silver nanoparticles (Ag-NPs) on ion-beam-fabricated nanorippled silicon substrates, a system relevant for creating substrates with tailored plasmonic properties [26].

Materials and Reagents

- Substrate: Silicon (100) wafer, 1x1 cm².

- Cleaning Solvents: Acetone, distilled water, and isopropyl alcohol for ultrasonic cleaning.

- Sputtering Target: High-purity (99.99%) silver target for nanoparticle deposition.

- Process Gases: High-purity argon (Ar) for the ion beam source and sputtering process.

Step-by-Step Procedure

- Substrate Preparation:

- Cut a silicon wafer to 1x1 cm² pieces.

- Ultrasonically clean the substrates sequentially in acetone, distilled water, and isopropyl alcohol for 5 minutes each to ensure a pristine surface [26].

- Ripple Pattern Fabrication:

- Load the cleaned substrate into an ultra-high vacuum (UHV) chamber with a base pressure of 1x10⁻⁷ mbar.

- Use a broad ion beam source (e.g., Kaufman type) with Ar⁺ ions at 2 keV energy.

- Set the ion incidence angle to 65° relative to the surface normal.

- Maintain a constant working pressure of 2x10⁻⁴ mbar during irradiation to create the nanoripple pattern [26].

- Sequential Nanoparticle Deposition:

- Transfer the patterned substrate to a DC magnetron sputtering chamber without breaking vacuum.

- Use a high-purity Ag target in an Ar atmosphere at 0.02 mbar.

- For sequential deposition, rotate the substrate to deposit Ag from two opposing directions relative to the ripple axis. For example, deposit for a duration t₁ from one side, then for t₂ from the opposite side [26].

- Control the deposition rate and total time to achieve the desired nanoparticle coverage and size.

- GISAXS Data Collection:

- Align the sample at a grazing incidence angle (typically < 1°) to maximize surface sensitivity.

- Use a 2D X-ray detector (e.g., Pilatus or Eiger) to collect the scattering pattern.

- Ensure the beamline is calibrated to convert pixel position to scattering vector components qy (in-plane) and qz (out-of-plane).

Data Analysis and Key Findings

The structural parameters extracted from GISAXS analysis provide quantitative insight into nanoparticle morphology and ordering.

- Asymmetric Ripple Morphology: GISAXS analysis of the bare rippled substrate revealed an inherent asymmetry, with slopes of approximately 6.4° and 6.9° on the two sides of the ripples [26].

- Impact of Sequential Deposition: Compared to single-direction deposition, which resulted in elongated, ellipsoidal nanoparticles (aspect ratio ~1.5), sequential deposition from both sides promoted the formation of more uniform, truncated spherical nanoparticles [26].

Table 1: Quantitative Structural Parameters from GISAXS/GIWAXS Analysis of Ag-NPs on Rippled Si [26]

| Deposition Configuration | NP Morphology | Aspect Ratio (a/b) | Crystalline Size Ratio (D⊥/D‖) | Key Finding |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Along Ion Beam (Ag60in) | Ellipsoidal | 1.45 | --- | Anisotropic growth along ripple direction |

| Opposite Ion Beam (Ag60opp) | Ellipsoidal | 1.50 | --- | Anisotropic growth along ripple direction |

| Sequential (Ag60seq) | Truncated Spherical | ~1.0 (near-spherical) | Decreased | Reduced anisotropy, more uniform morphology |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Software for GISAXS Analysis

A variety of software packages are available for viewing, reducing, modeling, and fitting GISAXS data. There is no single universal package, and the choice often depends on the specific analysis needs [14].

Table 2: Key Software for GISAXS Data Analysis [14]

| Software Name | Primary Function | Key Features / Applications | Requirements / Language |

|---|---|---|---|

| IsGISAXS | Simulation & Analysis | Predicts 2D scattering patterns using DWBA; well-established | Standalone |

| BornAgain | Simulation & Fitting | Modern implementation of DWBA; polarized GISAXS/GISANS; extensive fitting | Python/C++ |

| HipGISAXS | Simulation | High-performance, massively parallel simulation of complex structures | C++ |

| FitGISAXS | Simulation & Fitting | DWBA modeling for GISAXS patterns | Igor Pro |

| GIXSGUI | Visualization & Reduction | Data reduction and visualization for GISAXS | MATLAB |

| GISA XSshop | Visualization & Reduction | 2D visualization and data reduction for GISAXS | Igor Pro |

| GIXS Tools | Visualization & Reduction | Data reduction and visualization for GISAXS | MATLAB |

| SciAnalysis | Batch Analysis | Suite of Python scripts for batch analysis of 2D x-ray data | Python |

Interpreting GISAXS patterns is a critical skill for extracting meaningful nanostructural information. The patterns serve as a fingerprint, revealing the degree of order, orientation, and morphology in a thin film or nanoparticle system. The experimental case study on Ag-NPs demonstrates the power of GISAXS to probe growth mechanisms. The technique confirmed that sequential deposition compensates for the inherent asymmetry of rippled substrates, leading to more isotropic nanoparticle growth crucial for applications like Surface-Enhanced Raman Spectroscopy (SERS) where uniform "hotspot" density is key [26].

GISAXS, especially when combined with complementary techniques like GIWAXS (for crystalline structure) and MD simulations (for atomic-scale insights), provides a comprehensive picture of nanostructured surfaces [26]. Its ability to provide ensemble-averaged data makes it an indispensable tool in the field of nanoparticle characterization, bridging the gap between local probe microscopy and bulk-sensitive scattering techniques.

Practical Applications: From Thin Films to Liquid Interfaces and Drug Delivery Systems

Sample Preparation and Experimental Setup for Reliable GISAXS Data

Grazing-Incidence Small-Angle X-Ray Scattering (GISAXS) is an advanced, non-destructive technique for investigating the nanoscale structure of thin films, surfaces, and interfaces. For researchers in nanoparticle characterization, it provides statistically robust, representative information from a large sample area, complementing local probe techniques like Atomic Force Microscopy (AFM) and Transmission Electron Microscopy (TEM) [1]. The reliability of this powerful technique, however, is fundamentally contingent upon meticulous sample preparation and a rigorous experimental setup. This application note details the critical protocols required to obtain high-quality, reproducible GISAXS data, framed within the context of nanoparticle research.

Sample Preparation Protocols

Proper sample preparation is the most critical factor for successful GISAXS experiments. The following guidelines ensure that the sample itself does not introduce artifacts or complicate data interpretation.

Substrate Selection and Requirements

The choice of substrate is paramount, as it is the foundation for your thin film or nanoparticle assembly.

Table 1: Substrate Selection Guidelines for GISAXS

| Substrate Type | Key Characteristics | Ideal Applications | Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Silicon Wafer | Cheap, very smooth, flat, well-defined surface chemistry [27]. | Ideal for most applications, especially fundamental studies on nanoparticle ordering [27]. | The industry standard; first choice for most experiments. |

| Glass Microscope Slide | Reasonably smooth and flat [27]. | Lower-cost alternative for less demanding applications. | Higher roughness may yield more diffuse scattering [27]. |

| ITO (Indium Tin Oxide) | Conducting, moderately smooth. | Experiments requiring an electrical contact. | Roughness of coatings must be considered [27]. |

The substrate must be macroscopically flat and microscopically smooth. Substrate roughness induces substantial diffuse scattering that can overwhelm the weak GISAXS signal from the nanostructure, while macroscopic bending or curvature makes sample alignment difficult and the incident angle ill-defined [27]. Note that processing steps like spin-coating can kink or bend even nominally flat substrates like silicon wafers [27].

Film and Nanoparticle Layer Specifications

The sample layer itself must be carefully prepared to yield a strong, interpretable scattering signal.

Table 2: Sample (Film/Nanoparticle Layer) Specifications

| Parameter | Optimal Range | Impact on GISAXS Measurement |

|---|---|---|

| Thickness | ~50 nm to ~300 nm [27]. | A balance between sufficient scattering volume and avoiding excessive roughness/absorption. |

| Sample Size | Ideal: ~10 mm × ~10 mm [27]. | Captures most of the X-ray beam and simplifies alignment. Smaller samples (down to 0.5 mm) are possible with reduced signal [27]. |

| Scattering Contrast | High electron density difference between nanoparticles and matrix/substrate [28]. | Defines scattering intensity. Low contrast (e.g., polymer nanoparticles in an organic matrix) requires longer exposure times [28]. |

Mitigation of Edge Effects

The GISAXS beam probes a long stripe of the sample. If this stripe includes the sample edge, artifacts from the deposition process can dominate the signal. For instance, spin-coated films often have a thicker "lip" at the edge, which produces an isotropic scattering pattern that can mask the anisotropy of the well-ordered central film [27]. To mitigate this, cleave the substrate to avoid edges or remove the edge material with a solvent-soaked swab or razor blade [27].

Experimental Setup and Workflow

A correct experimental geometry is essential for meaningful data collection and subsequent analysis.

Core GISAXS Geometry