Interfacial Phenomena: Fundamental Principles and Cutting-Edge Applications in Biomedical Research

This comprehensive review explores the critical role of physical and chemical phenomena at interfaces in advancing biomedical research and drug development.

Interfacial Phenomena: Fundamental Principles and Cutting-Edge Applications in Biomedical Research

Abstract

This comprehensive review explores the critical role of physical and chemical phenomena at interfaces in advancing biomedical research and drug development. It examines foundational principles governing molecular behavior at boundaries like air-water and solid-liquid interfaces, where unique properties enable breakthrough applications. The article details advanced characterization techniques including vibrational spectroscopy, scanning tunneling microscopy, and AI-enhanced molecular dynamics simulations that provide unprecedented insights into interfacial processes. For researchers and drug development professionals, it addresses key challenges in reproducibility, contamination, and data integration while presenting validation frameworks and comparative analyses of methodological approaches. By synthesizing recent discoveries with emerging trends in chiral materials, electrocatalysis, and digital twin technology, this resource demonstrates how interfacial science is revolutionizing drug delivery systems, diagnostic platforms, and sustainable pharmaceutical manufacturing.

The Hidden World at Boundaries: Fundamental Principles of Interfacial Phenomena

Interfaces—the boundaries between different phases or materials—are not merely passive frontiers but dynamic environments where molecular organization and behavior deviate significantly from bulk states. These unique interfacial phenomena, driven by asymmetrical force fields and heightened energy states, have profound implications across scientific disciplines, from catalysis and energy storage to targeted drug delivery. This whitepaper explores the fundamental principles governing these unique molecular environments, highlighting advanced characterization techniques and quantitative models that reveal the distinct physicochemical properties of interfaces. Framed within the broader context of physical and chemical phenomena at interfaces research, this guide provides methodologies and insights critical for researchers and drug development professionals seeking to harness interfacial effects for technological innovation.

At the most fundamental level, an interface represents a discontinuity in the properties of a system, a plane where one phase terminates and another begins. However, to view it as a simple two-dimensional boundary is a significant oversimplification. The interfacial region is a nano-environment with its own distinct composition, structure, and properties, often extending several molecular layers into each adjoining phase. Here, molecules experience an anisotropic force field, leading to orientations, packing densities, and reaction kinetics unobservable in the isotropic bulk environment. This article delves into the origin of these unique environments, their consequential effects on physical and chemical processes, and the advanced experimental and computational tools required to study them.

Theoretical Framework: The Physical-Chemical Origin of Interfacial Uniqueness

The distinct nature of interfaces arises from the interplay of several fundamental physical and chemical forces:

- Asymmetrical Molecular Interactions: Unlike molecules in the bulk, which experience relatively uniform forces from all directions, molecules at an interface are subject to an imbalanced force field. This asymmetry can lead to specific molecular orientations, altered conformational states, and the development of electrical potentials.

- Elevated Free Energy and Reactivity: The creation of an interface is energetically costly, resulting in a region of elevated surface free energy. This excess energy often manifests as enhanced chemical reactivity and lower activation barriers for reactions, making interfaces natural hotspots for catalysis.

- Confinement and Exclusion Effects: The spatial constraint at an interface can selectively concentrate certain molecules while excluding others, based on size, charge, or polarity. This can dramatically shift reaction equilibria and enable the self-assembly of complex structures not stable in the bulk.

Quantitative Manifestations: Data on Interfacial vs. Bulk Properties

The unique character of interfaces is quantitatively demonstrated by comparing key properties against their bulk counterparts. The following tables summarize critical differences observed in experimental and computational studies.

Table 1: Comparative Properties of Molecular Environments in Bulk vs. at a Model CO₂-Brine Interface

| Property | Bulk Aqueous Phase | Interfacial Region | Measurement/Conditions |

|---|---|---|---|

| Interfacial Tension (IFT) | N/A | 25 - 75 mN/m | Key parameter for CO₂ storage capacity; varies with P, T, salinity [1]. |

| CO₂ Diffusion Coefficient | Standard | Affected by IFT | IFT influences capillary trapping mechanism in sequestration [1]. |

| Ion Concentration (Na⁺, Cl⁻) | Homogeneous | Inhomogeneous Distribution | Affected by electrostatic interactions and hydration forces at the interface. |

| Water Molecular Orientation | Random | Highly Ordered | Hydrogen-bonding network is disrupted and reorganized at the interface. |

Table 2: Performance of Machine Learning Models in Predicting CO₂-Brine Interfacial Tension Accurate IFT prediction is critical for optimizing geological CO₂ sequestration. Machine learning models offer a cost-effective alternative to complex experiments [1].

| Machine Learning Model | Mean Absolute Error (MAE) | Mean Absolute Percentage Error (MAPE) | Key Application Insight |

|---|---|---|---|

| Support Vector Machine (SVM) | 0.39 mN/m | 0.97% | Best-performing model for accurate IFT prediction [1]. |

| Multilayer Perceptron (MLP) | 0.40 mN/m | 0.99% | High-performing alternative to SVM [1]. |

| Random Forest Regressor (RFR) | Metrics Not Specified | Metrics Not Specified | Useful for non-linear relationship modeling in IFT [1]. |

| Linear Regression (LR) | 1.7 mN/m | 4.25% | Demonstrates poor performance for this non-linear problem [1]. |

Experimental Protocols for Probing Interfacial Environments

Understanding these unique environments requires sophisticated experimental techniques that can probe molecular-scale structure and dynamics at interfaces.

Characterization of Metal-Organic Frameworks (MOFs)

Objective: To synthesize and characterize the porous structure and adsorption properties of Metal-Organic Frameworks (MOFs), which function as designed solid-gas interfaces [2].

Methodology:

- Synthesis: MOFs are formed by solvothermal reaction of metal ions (e.g., Zn²⁺, Cu²⁺, Zr⁴⁺) with organic linkers (e.g., terephthalate, imidazolates) in a solvent. The mixture is heated in a sealed autoclave to form crystalline frameworks [2].

- Gas Adsorption Analysis: The synthesized MOFs are activated (solvent removal) and then analyzed using gas sorption analyzers (e.g., with N₂ at 77 K or CO₂ at 273 K). The data is used to calculate specific surface area (via BET theory) and pore size distribution (via DFT or BJH methods) [2].

- Application Testing: The MOF's capacity is tested for specific applications, such as:

- PFAS Sequestration: Exposing the MOF to water contaminated with perfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS). Some MOFs are engineered to fluoresce when saturated, providing an indicator for replacement [2].

- Drug Delivery: In clinical trials (e.g., RiMO-301), MOFs are injected into tumors and activated with low-dose radiation to enhance cancer treatment efficacy [2].

Measuring Interfacial Tension (IFT) for CO₂ Sequestration

Objective: To accurately determine the IFT between CO₂ and brine (e.g., NaCl solution) under conditions relevant to geological sequestration [1].

Methodology:

- Sample Preparation: Prepare aqueous NaCl solutions of varying molality (e.g., 0-5 mol/kg) and purify CO₂ gas to >99.99% purity.

- Pendant Drop Method: a. A high-pressure visual cell is filled with the brine solution at a set temperature (T) and pressure (P). b. A droplet of CO₂ is carefully injected through a needle into the brine phase. c. The profile of the suspended droplet is captured using a high-resolution camera and back-lit with a diffuse light source. d. The IFT (γ) is calculated by fitting the droplet shape to the Young-Laplace equation using specialized software: γ = Δρ g R₀² / β, where Δρ is the density difference between the phases, g is gravity, R₀ is the droplet radius, and β is the shape factor.

- Data Collection: Measurements are repeated across a wide range of T (e.g., 300-400 K), P (e.g., 5-25 MPa), and NaCl molalities to build a comprehensive dataset for modeling [1].

Analysis via Scanning/Transmission Electron Microscopy (S/TEM)

Objective: To obtain high-resolution structural and chemical information on molecular machines and nanoscale interfaces [3].

Methodology:

- Sample Preparation: For soft molecular systems (e.g., proteins, synthetic molecular machines), samples may need to be stained with heavy metals (e.g., uranyl acetate) or rapidly frozen (cryo-preparation) to preserve native structure.

- Imaging and Analysis: a. STEM Imaging: The microscope is switched to scanning mode, and a focused electron beam is rastered across the sample. High-angle annular dark-field (HAADF) imaging can provide atomic number (Z)-contrast. b. Spectroscopy: Electron Energy Loss Spectroscopy (EELS) can be performed by analyzing the energy distribution of the transmitted electrons, providing information on elemental composition and bonding states at interfaces. c. X-ray Photoelectron Spectroscopy (XPS): As a complementary technique, XPS can be used to determine the surface chemical composition and electronic state of the elements within the top 1-10 nm of a sample [3].

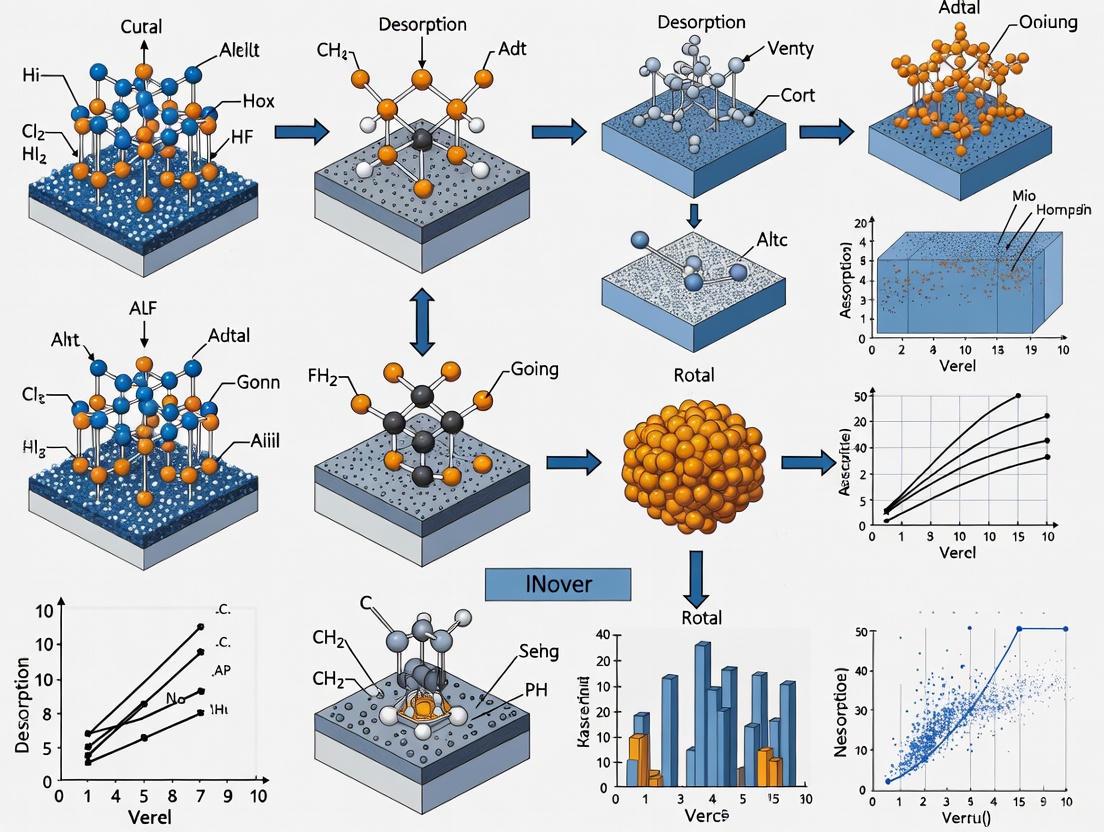

Visualization of Research Workflows

The following diagrams map the logical flow of key experimental and computational processes described in this field.

Research Pathway for Functional Materials

Machine Learning for IFT Prediction

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Key Reagents and Materials for Interfacial Molecular Research

| Item | Function/Application | Specific Example |

|---|---|---|

| Metal Salts | Source of metal ions (nodes) for constructing framework materials like MOFs. | Copper cyanide; Zinc nitrate [2]. |

| Organic Linkers | Molecular struts that connect metal nodes to form porous frameworks. | Terephthalic acid; Imidazolate [2]. |

| High-Purity Gases | Used in adsorption studies and as one phase in fluid-fluid interface studies. | Carbon dioxide (CO₂) for sequestration and IFT studies [1]. |

| Electron Microscopy Grids | Supports for holding nanoscale samples during S/TEM and EELS analysis. | Ultra-thin carbon film grids [3]. |

| Analytical Standards | Calibrants for spectroscopic techniques (e.g., XPS) and chromatography. | Certified PFAS mixtures for environmental analysis [2]. |

The air-water interface serves as a fundamental model for understanding the behavior of ions and biomolecules at hydrophobic boundaries. This review synthesizes current research on ion behavior at this critical interface, highlighting the sophisticated experimental and computational tools used to probe these interactions. We examine how ion-specific effects, driven by factors such as charge density, polarizability, and hydration enthalpy, influence interfacial organization and subsequently modulate biomolecular interactions, structure, and assembly. The insights gained from studying the air-water interface provide a foundational framework for understanding complex biological processes at cellular membranes and protein surfaces, with significant implications for drug development and biomaterial design.

The air-water interface represents the most fundamental and accessible model for studying hydrophobic interfaces, providing critical insights into phenomena spanning atmospheric chemistry, biomolecular engineering, and electrochemical energy storage [4] [5]. Traditionally viewed as a simple boundary, this interface is now recognized as a unique chemical environment with properties distinct from bulk water, where the hydrogen-bonded network is interrupted and water density is reduced [5]. Understanding how ions behave at this interface has emerged as a central challenge in physical chemistry, with profound implications for predicting biomolecular interactions.

Theoretical frameworks for describing ions at interfaces have evolved significantly beyond the classical Poisson-Boltzmann approach, which considers ions as obeying Boltzmann distributions in a mean electrical field [6]. Modern models incorporate ion-hydration forces that are either repulsive for structure-making ions or attractive for structure-breaking ions, with molecular dynamics simulations revealing that short-range attractions are crucial for explaining the behavior of structure-breaking ions at high ionic strengths [6]. This refined understanding has overturned the long-held assumption that all ions are repelled from the air-water interface due to electrostatic image forces, revealing instead that ion behavior is highly specific and depends on a complex interplay of size, polarizability, and hydration properties [7] [8].

Table 1: Key Ion Properties Influencing Interfacial Behavior

| Property | Effect on Interfacial Behavior | Representative Ions |

|---|---|---|

| Charge Density | Low charge density increases surface propensity | I⁻ > Br⁻ > Cl⁻ |

| Polarizability | High polarizability enhances surface activity | SCN⁻, I⁻ |

| Hydration Enthalpy | Weak hydration favors interfacial accumulation | Chaotropic ions |

| Size | Larger ions generally show greater surface stability | Tetraalkylammonium ions |

| Chemical Nature | Organic moieties enhance surface activity | Choline, TBA⁺ |

For biomedical researchers and drug development professionals, understanding these principles is essential because biological interfaces—from cellular membranes to protein surfaces—share fundamental characteristics with the air-water interface, yet exhibit additional complexity due to their chemical heterogeneity [7] [9]. The behavior of ions at these interfaces directly influences protein folding, molecular recognition, and self-assembly processes critical to physiological function and pharmaceutical intervention.

Fundamental Ion Behavior at Air-Water Interfaces

Specific Ion Effects and the Hofmeister Series

Ion behavior at air-water interfaces exhibits marked specificity that often follows the Hofmeister series, which ranks ions based on their ability to salt out or salt in proteins. This ranking correlates strongly with ion surface propensity, with chaotropic ions (e.g., I⁻, SCN⁻) displaying enhanced interfacial activity compared to kosmotropic ions (e.g., F⁻, Cl⁻) [7]. These differences originate from the balance between ion hydration energy and the disruption of water's hydrogen-bonding network at the interface.

Less strongly hydrated anions such as iodide and thiocyanate display a marginal interfacial stability compared with more strongly hydrated chloride anions [7]. This arises because larger, more polarizable anions have more dynamic hydration shells with less persistent ion-water interactions, allowing them to more readily accommodate the asymmetric solvation environment at the interface. The enthalpy-entropy balance of ion adsorption varies significantly between different interfaces, with air-water interfaces typically showing enthalpy-driven adsorption opposed by unfavorable entropy, while liquid hydrophobe interfaces can exhibit entropy-driven mechanisms [10].

Enhanced Ion-Ion Interactions at the Interface

A distinctive characteristic of the air-water interface is its ability to modify ionic interactions significantly. Research from Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute has demonstrated that oppositely charged ions attract each other much more strongly near an air-water interface than in bulk water [11]. More surprisingly, similarly charged ions, which strongly repel each other in bulk solution, exhibit reduced repulsion and may even attract each other when slightly displaced from the interface into the vapor phase.

This enhanced "stickiness" of ion-ion interactions arises from the complex interplay of water structure, surface deformation, and capillary waves along the water surface [11]. This phenomenon has profound implications for biomolecular assembly at interfaces, as it can influence the folding pathways of proteins and the association of biomolecules in the interfacial region. The ability to switch peptide structures between helical and hairpin turn conformations simply by charging the termini demonstrates how ion-ion interactions can dramatically influence biomolecular conformation at interfaces [11].

Table 2: Experimental Observations of Ion Behavior at Different Hydrophobic Interfaces

| Interface Type | Observed Ion Behavior | Primary Driving Force | Key Experimental Evidence |

|---|---|---|---|

| Air-Water | Enhanced concentration of large, polarizable anions | Favorable enthalpy (solvent repartitioning) | HD-VSFG, DUV-SHG, MD simulations |

| Graphene-Water | Dense ion accumulation with minimal water perturbation | Favorable enthalpy | HD-VSFG, machine-learning MD simulations |

| Liquid Hydrophobe-Water (toluene, decane) | SCN⁻ adsorption with similar free energy as air-water | Entropy increase | DUV-ESFG, Langmuir adsorption model |

| Protein-Water | Heterogeneous binding depending on local hydrophobicity | Ion-specific hydration properties | MD simulations of HFBII protein |

Experimental Methodologies for Probing Interfacial Ion Behavior

Surface-Specific Vibrational Spectroscopy

Vibrational sum-frequency generation (VSFG) spectroscopy has emerged as a powerful technique for probing molecular structure at interfaces, particularly the air-water interface [5]. As an inherently surface-specific method, VSFG derives its interface selectivity from the second-order nonlinear optical process that occurs only in media without inversion symmetry, such as interfaces between two bulk phases.

Heterodyne-detected VSFG (HD-VSFG) represents a significant technical advancement that provides direct access to the imaginary part of the nonlinear susceptibility (Im(χ(2)) [4]. This enables unambiguous determination of the net orientation of water molecules at interfaces: a positive sign in the Im(χ(2)) spectrum indicates O-H bonds pointing toward the interface (away from the liquid), while a negative signal indicates downward orientation into the bulk [4]. The technique is particularly valuable for characterizing how ions alter the hydrogen-bonding network of interfacial water, with different ions producing distinctive spectral signatures in the 3,000-3,600 cm⁻¹ region corresponding to O-H stretching vibrations.

Diagram 1: HD-VSFG workflow for interfacial water characterization.

Deep-Ultraviolet Second-Harmonic Generation (DUV-SHG)

Deep-ultraviolet second-harmonic generation (DUV-SHG) spectroscopy enables direct probing of specific anions at interfaces through their charge transfer to solvent (CTTS) transitions [10]. This technique is particularly valuable for determining Gibbs free energies of adsorption (ΔG°ad) for ions at various interfaces. The method involves measuring second-harmonic intensities as a function of bulk anion concentration and fitting the data to a Langmuir adsorption model.

The experimental setup typically involves generating deep-UV light (around 200-220 nm) through frequency doubling of visible laser pulses in nonlinear crystals, with the resulting beam incident on the interface at specific angles optimized for surface sensitivity. The intensity of the second-harmonic signal is proportional to the square of the surface susceptibility, which depends on the surface density of the adsorbing ion [10]. Temperature-dependent DUV-SHG measurements allow separation of the enthalpic (ΔH°ad) and entropic (ΔS°ad) contributions to the adsorption free energy, providing crucial mechanistic insights.

Molecular Dynamics Simulations

Molecular dynamics (MD) simulations provide atomic-level insights into ion behavior at interfaces that complement experimental findings. Modern simulations employ polarizable force fields that more accurately capture the electronic response of ions and water molecules to interfacial environments [7] [8]. These simulations typically utilize slab geometries with periodic boundary conditions to model the air-water interface.

Umbrella sampling techniques are frequently employed to compute potentials of mean force (PMFs) for ion transfer from bulk water to the interface, providing quantitative measures of ion surface stability [7]. More recently, machine-learning molecular dynamics simulations trained on first-principles reference data have enabled multi-nanosecond statistics with near-quantum accuracy, revealing complex ion hydration structures and their coupling to interface fluctuations [4]. These computational approaches have been instrumental in identifying the enhancement of ion-ion interactions at air-water interfaces and the molecular origins of specific-ion effects [11].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Key Research Reagents and Materials for Interfacial Ion Studies

| Reagent/Material | Function/Application | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| Sodium Salts of Chaotropic Anions (NaI, NaSCN) | Probe anion surface propensity | DUV-SHG studies of SCN⁻ adsorption [10] |

| Tetraalkylammonium Salts | Model organic cations with tunable hydrophobicity | MD simulations of interfacial behavior [8] |

| Hydrophobin-II (HFBII) Protein | Model protein with defined hydrophobic patches | Studying ion-specific effects at protein-water interfaces [7] |

| Graphene Surfaces | Well-defined hydrophobic solid interface | Comparing air-water vs. solid-water interfaces [4] |

| Deuterated Water | Control optical penetration depth | VSFG spectroscopy for reduced background [5] |

| Langmuir Trough Components | Control molecular density at interface | Study of mixed surfactant-ion monolayers |

Implications for Biomolecular Interactions

Protein Interfacial Behavior and Stability

The behavior of ions at air-water interfaces directly influences protein stability and conformational dynamics at hydrophobic surfaces. Research has demonstrated that the fundamental principles governing ion behavior at simple air-water interfaces can be extended to understand ion-specific effects near protein surfaces [7]. However, protein-water interfaces introduce additional complexity due to their chemical and topographical heterogeneity, where local environments of amino acid residues are perturbed by neighboring residues [7].

Studies on the hydrophobin-II (HFBII) protein have revealed that different anions induce distinct interface fluctuations at hydrophobic protein patches, with larger, less charge-dense anions like iodide inducing larger fluctuations than smaller anions like chloride [7]. These fluctuations correlate with the surface stability of the anions and their local hydration environments, ultimately influencing protein-protein interactions and aggregation propensity. The differential binding of anions to hydrophobic regions of proteins follows trends similar to those observed at the air-water interface, with larger, more polarizable anions showing enhanced affinity for hydrophobic patches [7].

Biomolecular Self-Assembly and Aggregation

The enhanced ion-ion interactions at air-water interfaces significantly influence biomolecular self-assembly processes [11]. The finding that oppositely charged ions attract more strongly near interfaces while similarly charged ions exhibit reduced repulsion provides a mechanism for facilitating biomolecular association at hydrophobic surfaces. This effect can drive the assembly of peptides and proteins into structures distinct from those formed in bulk solution.

The ability to switch peptide conformations between helical and hairpin turn structures by charging terminal groups demonstrates how subtle changes in interfacial ion interactions can dramatically alter biomolecular architecture [11]. This principle has important implications for understanding pathological protein aggregation in neurodegenerative diseases, as well as for designing functional biomaterials with tailored nanostructures. The interfacial environment can promote unfolding of proteins at interfaces, leading to aggregation pathways different from those in bulk solution [9] [11].

Implications for Drug Development

Understanding ion behavior at interfaces has direct relevance to pharmaceutical development, particularly in formulation design and delivery system optimization. The surface activity of pharmaceutical ions and excipients influences critical processes such as membrane permeation, protein binding, and absorption. Drug molecules with ionizable groups can exhibit altered interfacial behavior depending on local pH and ionic environment, affecting their distribution and activity.

The principles derived from air-water interface studies inform the design of targeted drug delivery systems, where controlled assembly at biological interfaces is essential for efficient cargo delivery. Additionally, understanding how ions modulate protein interactions at interfaces helps predict biocompatibility and stability of biologic therapeutics. The tools and methodologies developed for studying fundamental ion behavior—particularly HD-VSFG and MD simulations—are increasingly applied to characterize drug-membrane interactions and surface-mediated delivery platforms [4] [9].

The study of ion behavior at air-water interfaces has evolved from examining a simple model system to providing fundamental insights with broad implications for biomolecular interactions. The paradigm shift from viewing all ions as repelled from interfaces to recognizing their specific, often enhanced, surface activity has transformed our understanding of biological interfaces. However, recent research challenging the direct transferability of air-water interface principles to solid-water boundaries highlights the need for continued investigation of interface-specific mechanisms [4].

Future research directions should focus on multi-scale modeling approaches that connect molecular-level insights to macroscopic phenomena, and on developing even more sensitive experimental techniques capable of probing dynamic ion behavior with higher temporal and spatial resolution. The integration of advanced spectroscopy with machine-learning enhanced simulations presents a particularly promising path forward. For drug development professionals, translating these fundamental principles into predictive models for complex biological interfaces will enhance drug design, delivery system optimization, and therapeutic efficacy assessment.

The air-water interface continues to serve as both a foundational model system and a source of surprising discoveries that reshape our understanding of ion behavior and its profound influence on biomolecular interactions in health and disease.

{ remove this line and add the exact title from the user instruction as the Level 1 Heading }

Capillary Waves in Miscible Fluids: Redefining Interfacial Tension Concepts

An In-Depth Technical Guide

This whitepaper examines the paradigm-shifting evidence for the existence of capillary waves at the interface of miscible fluids, a phenomenon previously attributed exclusively to immiscible pairs. Groundbreaking research has quantitatively characterized the transition from an inertial regime (k \sim \omega^0) to a capillary regime (k \sim \omega^{2/3}) in co-flowing systems, enabling the direct measurement of a transient effective interfacial tension. This document provides a comprehensive technical overview of the theoretical foundation, experimental protocols, and quantitative findings. Furthermore, it explores the profound implications of these non-equilibrium interfacial phenomena for advanced applications, particularly in the optimization of lipid-based drug delivery systems, offering researchers a detailed guide to this emerging field.

Interfacial physical chemistry has long operated on the fundamental premise that interfacial tension, and the capillary waves it sustains, is a definitive property of immiscible fluid pairs. The discovery that miscible fluids can exhibit classic capillary wave behavior challenges this core concept and introduces a new class of non-equilibrium interfacial phenomena. These findings force a re-evaluation of interfacial dynamics in a wide range of scientific and industrial contexts, from geophysical flows to pharmaceutical manufacturing.

The ability to measure a transient interfacial tension in miscible systems opens a novel avenue for probing the earliest stages of mixing and complex fluid interactions. This is particularly relevant for drug development professionals working with lipid-based formulations, where the initial interfacial contact between a self-emulsifying drug delivery system (SEDDS) and gastrointestinal fluids can dictate the ensuing droplet size, solubility, and ultimately, drug bioavailability [12]. This guide synthesizes recent breakthroughs to provide researchers with the theoretical tools, experimental methodologies, and applied knowledge to leverage these insights in their own work on physical and chemical phenomena at interfaces.

Theoretical Framework: From Inertial to Capillary Regimes

The dispersion relation of waves on a fluid interface provides a direct link between their dynamic properties and the restoring forces at play. The recent confirmation of a capillary scaling in miscible fluids represents a fundamental shift in our understanding.

The Inertial Regime (k \sim \omega^0): In the absence of significant interfacial stresses, the propagation of interfacial waves is dominated by viscous dissipation and fluid inertia. In this regime, the wavenumber (k) (2π/λ) is largely independent of the wave frequency (\omega), resulting in the characteristic inertial scaling (k \sim \omega^0) [13]. This has been the expected and observed behavior for miscible fluids, where any interfacial stress was presumed negligible.

The Capillary Regime (k \sim \omega^{2/3}): For immiscible fluids with a finite interfacial tension (\Gamma), the dominant restoring force for short-wavelength disturbances is surface tension, leading to the classic capillary wave dispersion relation (k \sim \omega^{2/3}) [13]. The observation of this exact scaling at the boundary of miscible co-flowing fluids is the primary evidence for the existence of a transient, effective interfacial tension.

The transition from the inertial to the capillary regime is governed by the interplay between transient interfacial stresses, viscous dissipation, and confinement. The following diagram illustrates the conceptual relationship between these states and the key parameters that define them.

Experimental Evidence and Key Quantitative Data

The seminal work by Carbonaro et al. (2024-2025) provides the first direct observation and measurement of capillary waves between miscible fluids [14] [13] [15]. Their experimental setup involved co-flowing streams of deionized water and glycerol in rectangular polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS) microchannels. The instability was visualized optically, and the interface dynamics were reconstructed through image analysis to extract wavelength (λ), phase velocity (v_ph), and amplitude.

The data revealed a clear transition between the two theoretical regimes. At low flow rates of water, the system exhibited the constant wavelength characteristic of the inertial regime. As the flow rate increased, a maximum wavelength was observed, followed by a decline. Analysis of the dispersion relation in this declining regime confirmed the capillary wave scaling (k \sim \omega^{2/3}), allowing the team to back-calculate the effective interfacial tension and track its rapid decay on millisecond timescales [13].

Table 1: Key Experimental Parameters and Findings from Miscible Capillary Wave Studies

| Parameter | Inertial Regime | Capillary Regime | Measurement Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Dispersion Relation | (k \sim \omega^0) | (k \sim \omega^{2/3}) | Water-Glycerol co-flow [13] [15] |

| Effective Interfacial Tension | Negligible / Immeasurable | Transient, rapidly decaying | Measured on millisecond scales [14] |

| Wavelength (λ) | Constant with increasing frequency | Decreases with increasing frequency | Directly observed via optical microscopy [13] |

| Primary Fluids Used | Deionized Water (n = 1.333) & Glycerol (n = 1.472) | Co-flowing streams in PDMS microchannels [13] | |

| Channel Height (H) | 0.1 mm | Rectangular microchannel [13] | |

| Channel Width (W) | 1.0 mm and 0.25 mm | Used to investigate role of lateral confinement [13] |

Detailed Experimental Protocol

This section outlines a standardized protocol for replicating the key experiments on capillary waves in miscible co-flowing fluids, based on the methods established in the primary literature [13].

Microfluidic Wave Visualization

Objective: To generate and characterize capillary waves at the interface of miscible co-flowing fluids.

Materials & Reagents:

- Fluids: Deionized water and glycerol.

- Microfluidic Device: PDMS microchannel fabricated via soft lithography. The main duct should have a height (H) of 0.1 mm and a width (W) of 1.0 mm (or 0.25 mm for confinement studies), with a Y-shaped inlet geometry.

- Equipment: Syringe pumps (x2), high-speed optical microscope with a 10x objective, high-speed camera (capable of >1000 fps), and a computer with image analysis software (e.g., ImageJ, MATLAB).

Procedure:

- Channel Priming: Fill the entire microchannel with glycerol to prevent the introduction of air bubbles.

- Flow Rate Setup: Set the glycerol pump ((QG)) to a constant rate between 3–25 μL/min. Set the water pump ((QH)) to 0 μL/min initially.

- Flow Initiation: Start both pumps simultaneously. The glycerol stream should occupy one side of the channel and the water the other, forming a vertical, parallel interface.

- Critical Flow Determination: Gradually increase (QH) from 0 μL/min until the onset of instability is observed at a critical flow rate (Q^c{H_2O}). The instability will manifest as a traveling wave along the fluid-fluid boundary.

- Data Acquisition: For a fixed (QG), record the interface dynamics at multiple (QH) values above (Q^c{H2O}). Ensure recordings are taken at the instability onset, located a distance (\Delta X) downstream from the confluence point.

- Image Analysis:

- Interface Tracking: In each frame, track the position (Y) of the interface in the direction orthogonal to the flow to reconstruct the wave front.

- Parameter Extraction: Calculate the average wavelength (λ) from the spatial period of oscillations. Determine the phase velocity in the laboratory frame ((v{ph}^{lab})) by tracking wave crest propagation.

- Doppler Correction: Calculate the base flow velocity (U(Y, H/2)) at the unperturbed interface. The true phase velocity is (v{ph} = v{ph}^{lab} - U(Y, H/2)).

- Dispersion Analysis: Plot the wavenumber (k = 2\pi/\lambda) against the angular frequency (\omega = 2\pi v{ph}/\lambda) to identify the inertial ((k \sim \omega^0)) and capillary ((k \sim \omega^{2/3})) scaling regimes.

The workflow for this protocol, from preparation to data analysis, is summarized below.

Effective Interfacial Tension Calculation

Objective: To quantify the transient effective interfacial tension (EIT) from the capillary wave dispersion relation.

Procedure:

- Identify Capillary Scaling: From the dispersion plot, isolate the data points that conform to the (k \sim \omega^{2/3}) scaling.

- Apply Dispersion Model: For a confined system, use the appropriate form of the capillary dispersion relation for inviscid fluids, ( \omega^2 = \frac{\Gamma k^3}{\rho{eff}} ), where ( \rho{eff} ) is an effective density accounting for the two fluids, and (\Gamma) is the effective interfacial tension.

- Calculate EIT: Rearrange the equation to solve for (\Gamma): ( \Gamma = \frac{\omega^2 \rho_{eff}}{k^3} ). Use the measured values of (\omega) and (k) from the capillary regime to compute (\Gamma).

- Track Temporal Decay: By correlating the streamwise position of wave onset (\Delta X) with the flow velocity (U(Y, H/2)), compute the diffusion time (tc = \Delta X / U(Y, H/2)). Repeating the experiment at different (\Delta X) (or flow rates) allows for the construction of a (\Gamma) vs. (tc) curve, revealing the rapid temporal decay of the EIT.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Successful experimentation in this field requires specific materials to create and observe the transient interfacial phenomena.

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Miscible Capillary Wave Studies

| Item | Function / Role | Specific Example |

|---|---|---|

| Glycerol | High-viscosity, high-refractive index co-flowing fluid. Creates necessary viscosity contrast and optical discontinuity with water. | Anhydrous Glycerol (e.g., Sigma-Aldrich) [13] |

| Deionized Water | Low-viscosity, low-refractive index co-flowing fluid. The fast-moving fluid that drives the instability. | Milli-Q grade water (18.2 MΩ·cm) [13] |

| PDMS Microchannel | Provides confinement that is critical to the transition from inertial to capillary regime. | Sylgard 184 Elastomer Kit, fabricated to H=0.1mm, W=1.0mm [13] |

| Syringe Pumps | Deliver precise, steady flow rates of each fluid to establish stable co-flow and control shear. | Any high-precision dual-syringe pump system [13] |

| High-Speed Camera | Captures the fast dynamics of wave propagation for subsequent quantitative image analysis. | Camera capable of >1000 fps [13] |

Implications for Drug Delivery and Formulation Science

The discovery of transient interfacial tension in miscible systems has direct and significant implications for pharmaceutical research, particularly in the design of lipid-based formulations.

In Self-Emulsifying Drug Delivery Systems (SEDDS), the emulsion droplet size formed upon contact with gastrointestinal fluids is a critical parameter influencing drug solubility and absorption. Traditional strategies to reduce droplet size rely on high surfactant-to-oil ratios (SOR), which can compromise drug loading and cause gastrointestinal toxicity [12]. Recent research demonstrates a novel alternative: using a hybrid medium-chain and long-chain triglyceride (MCT&LCT) oil phase can drastically reduce emulsion droplet size without increasing surfactant concentration. One study achieved a reduction from 113.34 nm (MCT-only) and 371.60 nm (LCT-only) to 21.23 nm with the hybrid system [12]. This nanoemulsion led to a 3.82-fold increase in the bioavailability of progesterone compared to a commercial product in a mouse model [12]. The profound performance enhancement is likely governed by the complex interfacial dynamics and transient Marangoni stresses during emulsification, a direct parallel to the phenomena observed in miscible capillary waves.

The observation of capillary waves between miscible fluids fundamentally redefines the concept of an "interface" in physical chemistry, shifting it from a purely thermodynamic boundary to a dynamic, time-dependent entity. The experimental protocols and quantitative data outlined in this guide provide researchers with a roadmap to explore this nascent field. The ability to measure transient interfacial stresses offers a powerful new probe for understanding the initial moments of mixing in countless natural and industrial processes. For drug development professionals, these insights provide a mechanistic foundation for engineering next-generation formulations, where controlling non-equilibrium interfacial phenomena can directly translate to enhanced product performance and therapeutic outcomes. As research progresses, the integration of these concepts will undoubtedly unlock further innovations in interface science and material engineering.

The study of chiral materials at interfaces represents a cutting-edge frontier in physical and chemical sciences, focusing on the unique quantum mechanical interactions that occur when molecules with specific handedness meet solid surfaces. Central to this field is the Chiral-Induced Spin Selectivity (CISS) effect, a phenomenon in which chiral molecules preferentially transmit electrons of one spin orientation. This effect challenges conventional wisdom in multiple ways, as biological molecules where CISS occurs are typically warm, wet, and noisy—conditions traditionally considered hostile to delicate quantum effects. Moreover, these molecules often filter electrons based on a purely quantum property over distances much longer than those at which electron spins normally maintain their orientation. The CISS effect has profound implications across disciplines, offering potential breakthroughs in spintronics, quantum computing, enantioselective chemistry, and energy conversion technologies [16].

The fundamental principle underlying CISS revolves around molecular chirality—the geometric property of a molecule that exists in two non-superimposable mirror image forms, much like human left and right hands. Well-known examples include the drug thalidomide, where two mirror-image forms had drastically different biological effects: one therapeutic and the other causing severe birth defects [17]. When such chiral molecules interface with surfaces, particularly metallic electrodes, they can act as efficient spin filters without requiring external magnetic fields. This ability emerges from the intricate relationship between the molecule's structural asymmetry and quantum properties of electrons, especially their spin—a fundamental quantum property analogous to a tiny magnetic orientation [17] [18].

The CISS Effect: Mechanisms and Current Theoretical Frameworks

Experimental Manifestations and Key Characteristics

The CISS effect manifests experimentally in several distinct ways, each providing different insights into the underlying mechanisms. Photoemission CISS experiments involve electrons being photoexcited out of a non-magnetic metal surface covered with chiral molecules. The emerging photoelectrons exhibit significant spin polarization that depends on the handedness of the chiral molecules. In contrast, transport CISS (T-CISS) experiments measure electric current flowing through a junction where chiral molecules are sandwiched between metallic and ferromagnetic electrodes. The current-voltage characteristics vary depending on whether the ferromagnet is magnetized parallel or anti-parallel to the molecular chiral axis [18]. What distinguishes CISS from other chirality-related effects is its unique symmetry: flipping the molecular chirality reverses the preferred electron spin orientation, but this preference remains unchanged when reversing the direction of current flow [18].

A crucial feature of the CISS effect is its generality across diverse systems. The effect has been observed in small single-molecule junctions, intermediate-size molecules like helicene, large biomolecules including polypeptides and oligonucleotides, large chiral supramolecular structures, and even layers of chiral solid materials. This broad applicability suggests CISS represents a fundamental effect rather than a system-specific phenomenon. Another universal characteristic is the nearly ubiquitous involvement of metal electrodes in CISS experiments, whether as part of transport junctions or as substrates for chiral molecules in photoemission studies and magnetization measurements [18].

Theoretical Models and the Spinterface Mechanism

Despite more than two decades of research, no consensus theoretical framework fully explains the CISS effect. Multiple models have been proposed, but significant gaps remain between experimental observations and quantitative theoretical predictions [18]. Among the leading candidates is the spinterface mechanism, which hypothesizes a feedback interaction between electron motion in chiral molecules and fluctuating magnetic moments at the interface with metals. This model has demonstrated remarkable success in quantitatively reproducing experimental data across various systems and conditions [19] [18].

The spinterface model proposes that the interaction between chiral molecules and metal surfaces creates a hybrid interface region with unique spin-filtering properties. The chiral structure of the molecules couples with electron spin through spin-orbit interactions, while the metal surface provides the necessary breaking of time-reversal symmetry. This mechanism effectively creates a situation where electrons with one spin orientation experience lower resistance when passing through the chiral structure, leading to the observed spin selectivity. The model has been shown to account for key experimental features, including the dependence on molecular chirality, the magnitude of the spin polarization observed, and the effect's persistence across different length scales [18].

Table 1: Key Theoretical Models for the CISS Effect

| Model Name | Core Mechanism | Strengths | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Spinterface Mechanism | Feedback between electron motion in chiral molecules and fluctuating surface magnetic moments | Quantitative reproduction of experimental data across systems; explains interface magnetism | Nature of surface magnetism not fully understood |

| Spin-Orbit Coupling Models | Chiral geometry induces effective magnetic fields through spin-orbit coupling | Intuitive connection between structure and function; supported by some ab initio calculations | Struggles to explain magnitude of effect in some systems |

| Exchange Interaction Models | Chiral-mediated exchange interactions between electrons and nuclei | Provides mechanism for spin selection without strong spin-orbit coupling | Limited quantitative validation across diverse systems |

Quantitative Research Landscape and Computational Approaches

The research landscape for CISS involves sophisticated computational and experimental approaches designed to unravel the complex quantum dynamics at chiral interfaces. A major national effort led by UC Merced, supported by an $8 million grant from the U.S. Department of Energy, exemplifies the scale and ambition of current research initiatives. This project aims to address the fundamental challenge that "existing computer models struggle to replicate the strength of the effect seen in experiments" [17].

The UC Merced-led team employs a three-pronged computational strategy to overcome current limitations. First, quasi-exact modeling uses advanced wavefunction methods to solve the Schrödinger equation for small chiral molecules with near-perfect accuracy, creating benchmarks for testing more scalable approaches. Second, machine learning analyzes data from high-accuracy simulations to improve time-dependent density functional theory (TDDFT) for capturing complex spin dynamics in larger systems. Third, exascale computing harnesses supercomputers like Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory's El Capitan—one of the world's fastest—to simulate electron and nuclear motion in realistic materials, accounting for environmental factors like temperature and molecular vibrations [17].

Table 2: Quantitative Data in CISS Research

| Parameter Category | Specific Parameters | Typical Values/Ranges | Measurement Techniques |

|---|---|---|---|

| Spin Polarization | Photoemission asymmetry | 10-20% [16] | Spin-resolved photoemission spectroscopy |

| Transport magnetoresistance | Varies by system | Current-voltage measurements with magnetic electrodes | |

| Computational Scales | System sizes in simulations | Small molecules to large biomolecules | Wavefunction methods, TDDFT, machine learning |

| Energy Scales | Thermal energies at operation | Room temperature to millikelvin | Temperature-dependent measurements |

| Geometric Parameters | Molecular lengths | Single molecules to giant polyaniline structures | Scanning probe microscopy, structural biology |

Experimental Methodologies and Protocols

Core Experimental Approaches

Research into chiral materials at interfaces employs specialized experimental protocols tailored to probe spin-dependent phenomena. Photoemission CISS experiments typically begin with preparing a clean metal substrate (often gold or similar non-magnetic metals), followed by deposition of chiral molecules as organized films. Photoelectrons are then excited using light sources (often lasers or synchrotron radiation), with their spin polarization analyzed using spin-detection systems such as Mott polarimeters or spin-detecting electron multipliers. The key measurement involves comparing the spin polarization of emitted electrons for different molecular chiralities [18] [16].

For transport CISS measurements, researchers fabricate nanoscale junctions where chiral molecules bridge between electrodes. A common approach uses conductive atomic force microscopy (c-AFM), where one electrode is the AFM tip and the other is a substrate. Alternatively, break-junction techniques or nanopore setups can create stable molecular junctions. The experimental protocol involves measuring current-voltage characteristics while controlling the magnetization direction of ferromagnetic electrodes (often using external magnetic fields) and comparing results for different molecular enantiomers. The signature of CISS appears as different conductance states depending on the relative orientation between molecular chirality and electrode magnetization [18].

Engineered Chiral Systems as Quantum Simulators

A innovative approach to studying CISS effects involves programmable chiral quantum systems that serve as analog quantum simulators. Researchers at the University of Pittsburgh have developed a platform using the oxide interface between lanthanum aluminate (LaAlO₃) and strontium titanate (SrTiO₃). Using a conductive atomic force microscope (c-AFM) tip, they "write" electronic circuits with nanometer precision, creating artificial chiral structures by combining lateral serpentine paths with sinusoidal voltage modulation [16].

The experimental protocol involves several precise steps: first, preparing clean LaAlO₃/SrTiO₃ interfaces; second, using c-AFM with positive bias to create conductive pathways while following precisely programmed chiral patterns; third, performing quantum transport measurements at millikelvin temperatures to observe conductance oscillations and spin-dependent effects. This approach allows systematic variation of chiral parameters like pitch, radius, and coupling strength—something impossible with fixed molecular structures. The system has revealed surprising phenomena, including enhanced electron pairing persisting to magnetic fields as high as 18 Tesla and conductance oscillations with amplitudes exceeding the fundamental quantum of conductance [16].

Diagram 1: Experimental Workflow for CISS Studies. This flowchart illustrates the standard protocol for investigating spin selectivity in chiral molecular systems.

Research Reagents and Essential Materials

The experimental investigation of chiral materials at interfaces requires specialized materials and reagents carefully selected for their specific properties and functions. The table below details key components used in CISS research, drawing from current experimental methodologies across multiple research institutions.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for CISS Studies

| Material/Reagent | Function/Application | Specific Examples | Critical Properties |

|---|---|---|---|

| Chiral Molecules | Primary spin-filtering element | Helicenes, oligopeptides, DNA/RNA, chiral perovskites | High enantiomeric purity, structural stability, specific helical pitch |

| Metal Electrodes | Provide electron source/drain and interface for spinterface effect | Gold, silver, nickel, ferromagnetic metals | Surface flatness, work function, magnetic properties (for FM electrodes) |

| Oxide Interfaces | Programmable quantum simulation platform | LaAlO₃/SrTiO₃ heterostructures | 2D electron gas, nanoscale patternability, superconducting properties |

| Substrate Materials | Support for molecular films and device fabrication | Silicon wafers with oxide layers, mica, glass | Surface smoothness, electrical insulation, thermal stability |

| Characterization Tools | Analysis of structure and electronic properties | c-AFM, spin-polarized STM, XPS, spin-detectors | Nanoscale resolution, spin sensitivity, surface specificity |

Applications and Technological Implications

The CISS effect enables numerous technological applications across diverse fields. In spintronics, chiral molecules can function as efficient spin filters without requiring ferromagnetic materials or external magnetic fields, potentially enabling smaller, more efficient memory devices and logic circuits. For energy technologies, CISS offers pathways to improve solar cells through enhanced charge separation and reduced recombination losses. The effect also shows promise in enantioselective chemistry and sensing, where spin-polarized electrons from chiral electrodes could selectively promote chemical reactions of specific enantiomers, relevant for pharmaceutical development [17] [18].

Perhaps most intriguing are the implications for quantum technologies. The ability of chiral structures to generate and maintain spin-polarized currents at room temperature in biological systems suggests possibilities for robust quantum information processing. Research has demonstrated that chiral interfaces can support coherent oscillations between singlet and triplet electron pairs—a crucial requirement for quantum entanglement and spin-based qubits [16]. The programmable chiral quantum systems being developed offer a platform for engineering these quantum states with precision, potentially bridging the gap between biological quantum effects and solid-state quantum devices.

Diagram 2: CISS Application Landscape. This diagram illustrates the diverse technological applications emerging from the chiral-induced spin selectivity effect.

Future Research Directions and Open Questions

Despite significant progress, numerous fundamental questions about CISS remain unresolved. A central mystery concerns the microscopic origin of the effect, with ongoing debates between the spinterface mechanism, spin-orbit coupling models, and other theoretical frameworks. The field would benefit from crucial experiments that can discriminate between these models, such as systematic studies of temperature dependence, length scaling, and the role of specific molecular orbitals [18]. Particularly puzzling is how CISS achieves such high spin selectivity without strong spin-orbit coupling elements—a characteristic of many organic chiral molecules where the effect is observed.

Future research directions include developing hybrid chiral systems that combine molecular layers with programmable quantum materials. The Pittsburgh team, for instance, is working on integrating their oxide platform with carbon nanotubes, creating systems where chiral potentials can influence transport in separate electronic systems. This approach could help bridge the gap between engineered quantum systems and molecular CISS [16]. Similarly, the UC Merced-led collaboration aims to make their computational tools and data publicly available, enabling broader scientific community engagement with these challenging problems [17].

Another critical direction involves extending CISS studies to non-helical chiral systems and electrode-free configurations, which would test the generality of proposed mechanisms and potentially reveal new aspects of the phenomenon. Likewise, understanding the role of dissipation and decoherence in maintaining spin selectivity at room temperature remains a fundamental challenge with implications for both fundamental science and practical applications. As research progresses, the transdisciplinary nature of CISS studies—bridging physics, chemistry, materials science, and biology—will likely yield unexpected insights and applications beyond those currently envisioned.

The electrified interface between an electrode and an electrolyte is a central concept in electrochemistry, governing processes critical to energy conversion, biosensing, and electrocatalysis [20] [21]. At the heart of this interface lies water—not merely a passive solvent but a dynamic, structurally complex component that actively participates in and modulates electrochemical phenomena. The structure and orientation of water molecules at charged surfaces directly influence electron transfer kinetics, proton transport, and the stability of reaction intermediates [22].

Understanding water's behavior at electrode interfaces is particularly crucial for biosensing applications, where the recognition event occurs within the electrical double layer (EDL). The physicochemical properties of interfacial water affect bioreceptor orientation, target analyte diffusion, and the signal-to-noise ratio of the biosensor [23] [24]. This in-depth technical guide explores the fundamental principles of interfacial water structure, its experimental characterization, and its profound implications for the design and performance of electrochemical biosensors and related technologies, framed within the broader context of physical and chemical phenomena at interfaces.

Fundamental Properties of Interfacial Water

Structural Typology and Hydrogen-Bonding Networks

Interfacial water molecules, influenced by the applied potential, electrode surface chemistry, and dissolved ions, assemble into distinct structural types that differ significantly from the bulk water network [22]. These structures are primarily defined by their coordination and hydrogen-bonding patterns.

- Dangling O–H Water: This configuration features water molecules with O–H bonds weakly interacting with the electrode surface, leaving the other end pointing into the solution. These dangling O–H groups facilitate proton transfer through the breaking and reformation of O–H bonds, which is critical for reactions like the Hydrogen Evolution Reaction (HER) [22].

- Dihedral and Tetrahedral Coordinated Water: These water molecules integrate into more extensive hydrogen-bonding networks. Dihedral coordinated water often acts as a bridge in the hydrogen-bond chain, while tetrahedral coordinated water forms a more rigid, ice-like local structure [22].

- Hydrated Ions: Cations and anions in the electrolyte retain their hydration shells, which are networks of water molecules organized around the ion. The structure and stability of these shells, such as those of Na⁺ and Cl⁻, are perturbed within the intense electric field of the EDL [21].

The following table summarizes the key structural types and their characteristics.

Table 1: Structural Types of Interfacial Water and Their Properties

| Structural Type | Description | Proposed Role in Electrocatalysis/Biosensing |

|---|---|---|

| Dangling O–H Water | O–H bond weakly interacting with the electrode surface; the other end is suspended in the liquid phase. | Facilitates proton transfer; enhances water dissociation activity for HER [22]. |

| Tetrahedral Coordinated Water | Water molecules forming a local, ice-like structure with a rigid hydrogen-bond network. | Can create a "soft liquid-liquid interface"; may impede mass transport [21] [22]. |

| Hydrated Ions | Water molecules structured around ions (e.g., Na⁺, Cl⁻) forming a hydration shell. | Modifies the free energy for ion adsorption; its stability affects ion approach to the electrode [21]. |

| Free Water | Water molecules with a less rigid, disrupted hydrogen-bond network. | Promotes HER activity by facilitating faster water dissociation and ion transport compared to rigid networks [25]. |

Molecular Orientation and Network Rigidity

The orientation of water molecules at an interface is highly sensitive to the applied electric field. On a gold surface, for instance, water molecules can lie flat, forming a two-dimensional hydrogen-bond (2D-HB) network parallel to the surface [21]. When a negative potential is applied, water molecules reorient their hydrogen atoms toward the gold surface, disrupting this 2D-HB network [21]. This reorientation is a key factor in the formation of the EDL.

The concept of network rigidity differentiates "ice-like" (more rigid) from "liquid-like" (less rigid) interfacial water. The growth of rigid, ice-like networks can slow down water dissociation and impede the transport of ions to the catalyst surface, thereby negatively impacting reaction kinetics. In contrast, "free water" interfaces with disrupted hydrogen bonding have been shown to promote HER activity [25].

Experimental Characterization of Interfacial Water

Probing the molecular structure of water at electrode interfaces under operating conditions (operando) remains a significant challenge due to the dominance of bulk water signals and the weak nature of water-surface interactions [26]. A combination of advanced spectroscopic techniques has been developed to overcome these hurdles.

Core Spectroscopic Techniques

- Terahertz (THz) Spectroscopy: This technique probes the low-frequency intermolecular region (10-700 cm⁻¹), which is a direct fingerprint of the hydrogen-bond network and ion hydration shells. Using ultrabright synchrotron light, THz spectroscopy can track the stripping away of hydration shells (e.g., of Na⁺ and Cl⁻) during EDL formation at an electrode [21].

- Vibrational Spectroscopy (Raman and FTIR):

- Surface-Enhanced Raman Spectroscopy (SERS): Leverages plasmonic nanoparticles to dramatically enhance the Raman signal, providing high sensitivity for probing interfacial water structure and its role in reactions like HER and CO2 reduction [20].

- Fourier-Transform Infrared Spectroscopy (FTIR): Includes methods like external reflection (FTIR-RAS) and the more surface-sensitive Attenuated Total Reflection Surface-Enhanced IRAS (ATR-SEIRAS). These are powerful for identifying molecular vibrations and reaction intermediates at the interface [20].

- Nonlinear Optical Techniques: Sum Frequency Generation (SFG) spectroscopy is a highly surface-sensitive technique with strict selection rules that inherently suppress bulk water signals, making it ideal for resolving the structure of the topmost water layer at interfaces [26].

Table 2: Key Experimental Techniques for Probing Interfacial Water

| Technique | Key Principle | Key Advantage | Representative Insight |

|---|---|---|---|

| THz Spectroscopy | Probes low-frequency intermolecular vibrations and hydration shells. | Directly measures hydrogen-bond network dynamics and ion hydration. | Revealed contrasting hydration shell stripping for Na⁺ vs. Cl⁻ at Au electrodes [21]. |

| Surface-Enhanced Raman Spectroscopy (SERS) | Raman signal amplified by plasmonic nanoparticles. | High sensitivity for probing confined regions and reaction interfaces. | Unraveled structures of H-bonded water and cation-hydrated water during HER [20] [22]. |

| ATR-SEIRAS | IR absorption enhanced by a plasmonic film on an ATR prism. | Exceptional surface sensitivity for adsorbed species and interfacial water. | Enabled evaluation of water structure under localized surface plasmon resonance [20]. |

| Sum Frequency Generation (SFG) | Second-order nonlinear process that is forbidden in centrosymmetric media (e.g., bulk water). | Inherently surface-specific, capable of quantifying H-bond strength. | Can resolve hydrogen bonds and quantify charge transfer in water molecules [26] [22]. |

Experimental Workflow for Probing Interfacial Water

The following diagram outlines a generalized workflow for characterizing interfacial water structure using a combination of the techniques discussed.

Diagram 1: Workflow for characterizing interfacial water structure.

Implications for Biosensing and Electroanalysis

The structure and dynamics of interfacial water directly impact the critical performance parameters of electrochemical biosensors, including sensitivity, reproducibility, and response time.

The Biosensor/Electrolyte Interface

In electrochemical biosensors, the electrode is functionalized with a biorecognition element (e.g., an antibody, enzyme, or aptamer). The water layer adjacent to this functionalized surface is part of the transduction environment.

- Bioreceptor Immobilization and Orientation: The use of three-dimensional (3D) immobilization surfaces, such as hydrogels, porous silica, or metal-organic frameworks, increases probe loading and influences the local water structure. The porosity and hydrophilicity of these materials dictate the rigidity and connectivity of the water network within them, which can affect the accessibility of the target analyte to the capture probes [24].

- Signal Transduction and Reproducibility: The stability and reproducibility of a biosensor are heavily influenced by the consistency of the electrode-electrolyte interface. Fluctuations in the interfacial water structure, driven by changes in local pH or ion concentration, can alter the dielectric properties and capacitance of the EDL, leading to signal drift [23]. A well-controlled and understood interfacial water environment is therefore essential for reliable measurements.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

The following table details key materials and reagents used in the study of interfacial water and the development of advanced electrochemical biosensors.

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Interfacial and Biosensing Studies

| Category | Item | Function/Explanation |

|---|---|---|

| Electrode Materials | Gold (Au) Grid/Film | Common working electrode for fundamental studies due to its chemical inertness and excellent plasmonic properties for SERS/SEIRAS [21] [20]. |

| Glassy Carbon | A versatile electrode material often used as a substrate for biosensor functionalization [23]. | |

| Nanomaterials | Gold Nanoparticles (AuNPs) | Used for electrodeposition on electrodes to create a 3D surface, enhancing bioreceptor loading and providing SERS activity [24] [20]. |

| Graphene Oxide & 3D Graphene | Carbon-based nanostructures that provide a high-surface-area 3D scaffold for probe immobilization and facilitate electron transfer [24]. | |

| Electrolytes | Alkali Metal Chlorides (e.g., NaCl) | Model electrolytes for studying cation-specific effects (e.g., Na⁺, K⁺, Li⁺) on the interfacial water network and electrocatalytic activity [20] [21]. |

| Probes | Aptamers / Antibodies | Biorecognition elements immobilized on the 3D electrode surface to specifically capture target analytes like influenza viruses [24]. |

Water at the electrode interface is a dynamic and structurally complex entity whose properties extend far beyond those of a simple solvent. Its typology, orientation, and hydrogen-bonding network are critical factors that govern mass transport, proton transfer, and electron kinetics in electrochemical systems. A precise understanding of these factors, enabled by advanced spectroscopic tools, is fundamental to rational design in electrocatalysis and biosensing. For biosensors, engineering the interface to control water structure—for instance, through the use of tailored 3D matrices and optimized surface chemistry—offers a promising pathway to achieving superior sensitivity, stability, and reproducibility. Future research will continue to unravel the complex interplay between interfacial water, ions, and biomolecules, driving innovations in drug development, diagnostic tools, and energy technologies.

Advanced Characterization and Biomedical Applications of Interface Science

Vibrational spectroscopy provides a powerful, label-free toolkit for interrogating the physical and chemical phenomena occurring at interfaces, spanning from the scale of individual molecules to complex cellular systems. These techniques, primarily infrared (IR) and Raman spectroscopy, detect characteristic bond vibrations to reveal the biochemical composition, structure, and dynamics of interfacial species. The study of interfaces is crucial across numerous scientific domains, including catalysis, electrochemistry, biomedicine, and materials science, where molecular-level processes dictate macroscopic behavior and function. By harnessing both linear and nonlinear optical effects, vibrational spectroscopy offers unparalleled insights into adsorbate identity and orientation, bond formation and dissociation, energy transport, and lattice dynamics at surfaces.

The application of these techniques to biological interfaces, particularly in the context of drug-cell interactions, represents a rapidly advancing frontier. Here, vibrational spectroscopy serves as a critical tool for understanding the fundamental mechanisms governing cellular responses to therapeutic compounds, providing a biochemical fingerprint of efficacy and mode of action beyond what traditional, label-dependent methods can reveal. This technical guide explores the current methodologies, applications, and experimental protocols bridging single-molecule sensitivity and cellular-level analysis, framing the discussion within the broader context of interfacial science research.

Fundamental Principles and Techniques

Core Spectroscopic Techniques

Vibrational spectroscopy at interfaces encompasses several complementary techniques, each with unique mechanisms and information content. Infrared (IR) Spectroscopy measures the absorption of infrared light by molecular bonds, requiring a change in dipole moment during vibration. When applied to surfaces, Attenuated Total Reflection Fourier Transform IR (ATR-FTIR) spectroscopy is particularly valuable, enabling the study of thin films and adsorbed species with enhanced sensitivity. In contrast, Raman Spectroscopy relies on the inelastic scattering of light, involving a shift in photon energy corresponding to molecular vibrational levels; this process requires a change in polarizability and is inherently less efficient than IR absorption but offers superior spatial resolution and compatibility with aqueous environments.

The need for interfacial specificity drove the development of second-order nonlinear techniques, primarily Sum Frequency Generation Vibrational Spectroscopy (SFG-VS). SFG-VS combines a fixed-frequency visible beam with a tunable infrared beam to generate a signal at the sum frequency. This process is inherently forbidden in centrosymmetric media under the electric dipole approximation but is allowed at interfaces where inversion symmetry is broken. Consequently, SFG-VS is exclusively sensitive to the interfacial layer, making it a powerful tool for probing molecular orientation, ordering, and kinetics at buried interfaces, such as those between solids and liquids.

Enhancement Mechanisms for Ultrasensitive Detection

Achieving high sensitivity, particularly for single-molecule detection, requires signal enhancement strategies. Surface-Enhanced Raman Spectroscopy (SERS) utilizes the plasmonic properties of roughened metal surfaces or nanoparticles to amplify Raman signals by factors up to 10¹⁵, enabling the detection of trace analytes and even single molecules. Recent advancements employ sophisticated nanocavities, such as the Nanoparticle-on-Mirror (NPoM) structure, where a metal nanoparticle is separated from a metal film by a nanoscale gap. This configuration creates intensely localized optical fields, dramatically enhancing sensitivity [27].

Nonlinear techniques can be similarly enhanced. The novel NPoM-SFG-VS technique integrates femtosecond SFG-VS with NPoM nanocavities, achieving single-molecule-level sensitivity for probing interfacial structure and ultrafast dynamics. This approach has successfully detected signals from self-assembled monolayers comprising approximately 60 molecules, determining dephasing and vibrational relaxation times with femtosecond resolution [27]. Further pushing the boundaries of speed and sensitivity, nonlinear Raman techniques like Coherent Anti-Stokes Raman Spectroscopy (CARS) and Stimulated Raman Spectroscopy (SRS) overcome the inherent weakness of spontaneous Raman scattering, enabling rapid, high-resolution imaging vital for high-throughput applications and live-cell studies [28] [29].

Table 1: Key Vibrational Spectroscopy Techniques for Interfacial Analysis

| Technique | Fundamental Process | Key Strengths | Primary Applications at Interfaces |

|---|---|---|---|

| IR Spectroscopy | Infrared light absorption | Label-free, quantitative biochemical information | Bulk characterization, thin films (via ATR) |

| Raman Spectroscopy | Inelastic light scattering | Low water interference, high spatial resolution | Chemical imaging of cells and materials |

| SFG-VS | Second-order nonlinear optical mixing | Inherent interfacial specificity, molecular orientation | Buried liquid-solid and liquid-gas interfaces |

| SERS | Surface-enhanced Raman scattering | Extreme sensitivity (to single-molecule level) | Trace detection, catalysis, single-molecule studies |

| SRS/CARS | Coherent nonlinear Raman scattering | Fast acquisition, high spatial resolution | High-speed chemical imaging, live-cell tracking |

Single-Molecule Level Detection and Analysis

Ultrasensitive Techniques and Experimental Protocols

The frontier of single-molecule detection has been breached by combining plasmonic nanocavities with vibrational spectroscopy. The following protocol for NPoM-SFG-VS outlines the process for achieving single-molecule-level sensitivity, as demonstrated in the detection of para-nitrothiophenol (NTP) [27]:

- Substrate Preparation: A smooth gold film is fabricated on a suitable support (e.g., silicon wafer) using standard deposition techniques like electron-beam evaporation or sputtering to ensure a high-quality, plasmonically active surface.

- Self-Assembled Monolayer (SAM) Formation: The gold substrate is immersed in a solution of the target molecule (e.g., NTP) at a defined concentration for a controlled period. For single-molecule-level studies, concentrations ≤ 10⁻¹⁰ M are used, resulting in a sparse distribution of molecules on the surface.

- Nanocavity Fabrication: Gold nanoparticles (e.g., ~55 nm diameter) are deposited onto the molecule-functionalized gold film. This creates the NPoM structure, where the nanoparticle and the film are separated by the molecular monolayer, forming a plasmonic nanocavity.

- NPoM-SFG-VS Measurement: The sample is probed using a femtosecond SFG-VS setup in a non-collinear geometry. A tunable infrared laser pulse is spatiotemporally overlapped with a fixed-frequency visible laser pulse on the NPoM nanocavity.

- Signal Acquisition and Mapping: The generated SFG signal is collected. Due to the sparse molecular distribution at low concentrations, signals are not uniform across the surface, requiring deliberate mapping to locate "hot spots" of intense enhancement, often at the periphery of the gold film.

This technique's single-molecule-level sensitivity (~60 molecules) was confirmed by systematically diluting the NTP solution used for SAM formation and observing the corresponding signal attenuation and eventual disappearance, alongside a characteristic redshift in the vibrational frequency due to weakened intermolecular coupling [27].

Probing Ultrafast Dynamics

The NPoM-SFG-VS platform transcends structural detection to probe ultrafast vibrational dynamics. By employing femtosecond time-delayed pulses, it is possible to measure processes such as vibrational dephasing and energy relaxation. For the symmetric stretching mode of the nitro group (νNO₂) in NTP at the single-molecule level, the dephasing time (T₂) was measured at 0.33 ± 0.01 ps and the vibrational relaxation time (T₁) at 2.2 ± 0.2 ps [27]. These parameters are fundamental to understanding energy flow and lifetime at interfaces, with implications for controlling surface reactions and plasmonic processes.

Diagram 1: NPoM-SFG-VS Single-Molecule Detection Workflow

Cellular Systems and Biomedical Applications

Monitoring Drug-Cell Interactions

Vibrational spectroscopy has emerged as a powerful tool for pre-clinical drug screening and for investigating the interaction between pharmaceutical compounds and cellular systems. The primary advantage over conventional high-throughput screening (HTS) methods—which typically rely on fluorescent assays probing a single, specific interaction—is its label-free and multiplexed capability. IR and Raman spectroscopy provide a global biochemical snapshot of the cell, revealing not just whether a drug is effective, but also offering insights into its mode of action (MoA) by tracking changes in proteins, lipids, and nucleic acids simultaneously [28].

This approach is particularly valuable in anticancer drug development. Studies using IR microspectroscopy have successfully monitored the spectral signatures of cancer cells in response to various chemotherapeutic agents, identifying drug-specific biochemical responses. Similarly, Raman spectroscopy has been employed to track drug-induced changes in lipid metabolism and protein synthesis, providing a non-destructive means to classify drug efficacy and understand resistance mechanisms. The move towards high-throughput vibrational spectroscopic screening aims to accelerate drug discovery by providing a more information-rich and physiologically relevant alternative to existing univariate assays [28].

Protocol for Drug-Cell Interaction Study via Raman Spectroscopy

A typical protocol for assessing drug-cell interactions using Raman spectroscopy involves the following steps [28]: