LEED Surface Structure Analysis: A Comprehensive Guide for Materials Research and Biomedical Innovation

This article provides a comprehensive overview of Low-Energy Electron Diffraction (LEED), a powerful technique for determining the atomic-scale structure of surfaces.

LEED Surface Structure Analysis: A Comprehensive Guide for Materials Research and Biomedical Innovation

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive overview of Low-Energy Electron Diffraction (LEED), a powerful technique for determining the atomic-scale structure of surfaces. Tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, it covers the foundational principles of electron-surface interactions, detailed methodological procedures for qualitative and quantitative analysis, and advanced strategies for troubleshooting and data optimization. By comparing LEED with complementary techniques like Surface X-ray Diffraction (SXRD) and Reflection High-Energy Electron Diffraction (RHEED), it validates its unique role in surface science. The scope extends to applications in semiconductor manufacturing, catalysis, and the emerging potential for analyzing biological interfaces and drug delivery systems, providing a critical resource for advancing surface-sensitive research.

The Principles of LEED: Understanding Electron Diffraction at Surfaces

Low-Energy Electron Diffraction (LEED) is a premier technique for determining the surface structure of single-crystalline materials [1] [2]. The experiment involves directing a collimated beam of low-energy electrons (typically in the range of 20-300 eV) at a crystalline sample and observing the resulting diffraction pattern of elastically scattered electrons on a fluorescent screen [3] [2]. The key to LEED's surface sensitivity lies in the low kinetic energy of the electrons, which limits their penetration depth to just a few atomic layers (approximately 0.5-2 nm), making it exceptionally sensitive to surface structure as opposed to bulk properties [1] [2].

The historical development of LEED dates to the groundbreaking 1927 experiment by Clinton Davisson and Lester Germer at Bell Labs, which first demonstrated the wave-like nature of electrons by observing diffraction patterns from a nickel crystal [2]. However, LEED only became a standard surface science tool in the early 1960s with advances in ultra-high vacuum technology and the introduction of post-acceleration detection methods by Germer and colleagues [2]. This renaissance enabled the precise determination of surface structures that has become fundamental to modern surface science.

Table 1: Fundamental Characteristics of LEED

| Characteristic | Description | Significance |

|---|---|---|

| Electron Energy Range | 20 - 300 eV [3] [1] | Electron wavelength comparable to atomic spacings [3] |

| Penetration Depth | 0.5 - 2 nm (2-3 atomic layers) [4] | Provides exceptional surface sensitivity [1] |

| Primary Application | Determination of surface structure and symmetry [2] | Reveals surface reconstructions, adsorbate phases, and thin film structure [1] |

| Analysis Methods | Qualitative (spot positions) and Quantitative (I-V curves) [3] [1] | Qualitative reveals symmetry; quantitative reveals atomic positions [2] |

Theoretical Principles of Surface Electron Diffraction

The fundamental principle underlying LEED is wave-particle duality. The electron beam can be treated as an electron wave with a wavelength given by the de Broglie relation [3]:

[ \lambda = \frac{h}{p} = \frac{h}{\sqrt{2mE}} ]

where (h) is Planck's constant, (p) is the electron momentum, (m) is the electron mass, and (E) is the electron energy [3]. For typical LEED energies (20-200 eV), the electron wavelength ranges from approximately 2.7 to 0.87 Ångströms, which is comparable to interatomic distances in solids, thus satisfying the fundamental condition for diffraction [1].

When these electron waves interact with the periodic array of surface atoms, they are elastically scattered. Constructive interference occurs only at specific angles determined by the surface lattice arrangement, resulting in distinct diffraction spots [1]. The conditions for constructive interference are described by the Bragg condition in a one-dimensional model: (a \sin θ = nλ), where (a) is the atomic separation, (θ) is the scattering angle, (λ) is the electron wavelength, and (n) is an integer [3].

In practice, surface structure analysis employs two complementary approaches. Qualitative analysis focuses on the diffraction spot positions and pattern symmetry, revealing information about the size and rotational alignment of surface unit cells [3] [2]. Quantitative analysis, known as I-V analysis, involves measuring diffraction spot intensities as a function of incident electron beam energy and comparing these experimental I-V curves with theoretical simulations to determine precise atomic positions [2] [4].

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

LEED Instrumentation and Setup

A modern LEED apparatus operates under ultra-high vacuum conditions (typically <10⁻⁷ Pa) to maintain sample cleanliness and consists of several key components [2]:

Electron Gun: Emits a monochromatic, collimated electron beam with energies tunable between 20-300 eV. The beam is typically 0.1-0.5 mm in diameter and directed normal to the sample surface [2].

Sample Preparation Stage: Holds a single crystal specimen that can be precisely positioned. The sample must be cleaned in situ through cycles of ion sputtering and annealing to achieve a well-ordered surface structure. Sample alignment is critical and typically verified using X-ray diffraction methods such as Laue diffraction prior to insertion into the vacuum chamber [2].

Energy Filtering System: Consists of three or four hemispherical concentric grids that function as a retarding field analyzer. The first grid is at ground potential, the subsequent grids (suppressor grids) are at a negative potential to filter out inelastically scattered electrons, allowing only elastically scattered electrons to pass [2].

Detection System: A hemispherical fluorescent screen maintained at a high positive potential (5-10 kV) to accelerate the filtered electrons, producing visible diffraction patterns that can be captured with a CCD/CMOS camera or directly measured with position-sensitive electron detectors for quantitative analysis [2].

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Equipment for LEED Analysis

| Component | Specifications | Function |

|---|---|---|

| Single Crystal Samples | Precisely oriented (via Laue diffraction), surface purity verified by Auger spectroscopy [2] | Provides well-ordered surface for diffraction; purity essential for interpretable data |

| Electron Source | Tungsten or lanthanum hexaboride (LaB₆) cathode, energy range 20-300 eV, beam current 1 nA-1 μA [2] [4] | Generates monochromatic, low-energy electron beam with precise energy control |

| Grid Assembly | 3-4 concentric hemispherical grids, suppressor grid voltage: -V to ground [2] | Filters inelastically scattered electrons; ensures only elastic events contribute to pattern |

| Detection Systems | Fluorescent screen (5-10 kV acceleration), CCD camera, or delay-line detector [2] | Visualizes and records diffraction patterns; modern detectors enable quantitative I-V analysis |

| UHV System | Base pressure <10⁻⁷ Pa, ion pumps, turbo-molecular pumps [2] | Maintains surface cleanliness by minimizing contaminant adsorption |

Sample Preparation Protocol

Proper sample preparation is critical for obtaining meaningful LEED patterns. The following protocol ensures a clean, well-ordered surface:

Initial Characterization: Verify single crystal orientation using X-ray Laue diffraction prior to UHV insertion [2].

In Situ Cleaning:

- Sputtering: Expose the surface to argon ion bombardment (500 eV-2 keV, 10-20 μA/cm²) for 15-30 minutes to remove surface contaminants.

- Annealing: Heat the sample to high temperatures (typically 50-80% of melting point) for 1-5 minutes to reorder the surface lattice. Specific temperatures depend on the material.

- Cycling: Repeat sputtering and annealing cycles until surface cleanliness is confirmed by Auger electron spectroscopy [2].

Surface Quality Verification:

- Monitor surface composition using Auger electron spectroscopy to ensure contaminant levels below 1% atomic concentration.

- Check surface order by observing sharpness and low background of the LEED pattern [2].

Adsorbate Studies (if applicable):

- Expose the clean surface to controlled doses of gases using a precision leak valve.

- Typical exposures range from 0.1-100 Langmuirs (1 L = 10⁻⁶ Torr·sec).

- Anneal to desired temperature to achieve ordered adsorbate phases [2].

Data Acquisition Procedures

The specific data acquisition method depends on the type of LEED analysis being performed:

Qualitative Analysis Protocol:

- Set electron beam energy to 50-150 eV for optimal pattern visibility.

- Record diffraction pattern using CCD camera at multiple energies.

- Analyze spot positions to determine surface symmetry and unit cell dimensions.

- For adsorbate systems, identify superstructure periodicity relative to substrate [3] [2].

Quantitative I-V Analysis Protocol:

- Align sample precisely normal to incident beam.

- Select specific diffraction spots for intensity monitoring.

- Scan electron energy typically from 50-400 eV in 1-5 eV increments.

- Measure and record spot intensity at each energy using a photometer or position-sensitive detector.

- Repeat for multiple diffraction spots to generate comprehensive I-V datasets [2] [4].

Advanced Applications and Methodological Variations

Specialized LEED Techniques

The basic LEED methodology has evolved to address specific research challenges:

Fibre-Optic LEED (FO-LEED): This specialized approach uses extremely low beam currents (~1 nA) combined with fibre-optic coupling to a high-sensitivity CCD camera. This minimizes electron beam damage, making it suitable for studying sensitive materials such as water ice, ammonia, thiols, and physisorbed species that would otherwise degrade under conventional LEED conditions. FO-LEED systems often incorporate liquid helium cooling to further stabilize weakly bonded species and reduce thermal vibrations for more precise atomic position determination [4].

LEED for Surface Dynamics: Beyond static structure determination, LEED can probe surface dynamics through measurements of thermal vibration amplitudes and surface phase transitions as a function of temperature. The Debye-Waller factor, which describes the temperature dependence of diffraction spot intensities, provides information about surface atom vibrational properties.

Comparison with Related Techniques

LEED occupies a specific niche within the suite of surface analysis techniques. Compared to Reflection High-Energy Electron Diffraction (RHEED), which uses high-energy electrons (8-20 keV) at grazing incidence, LEED provides more straightforward interpretation of surface periodicity but less capability for in-situ growth monitoring [1].

Table 3: Comparison of LEED with RHEED for Surface Analysis

| Aspect | LEED | RHEED |

|---|---|---|

| Energy Range | 20-200 eV [1] | 8-20 keV [1] |

| Incidence Angle | Perpendicular or nearly perpendicular to surface [1] | Grazing incidence (1-5°) [1] |

| Diffraction Pattern | Distinct spots on fluorescent screen [1] | Elongated streaks or arcs [1] |

| Primary Applications | Surface structure analysis of bulk materials, adsorption sites, surface chemistry [1] | Thin film growth monitoring, epitaxy, in-situ monitoring during MBE [1] |

| Information Depth | Top 2-3 atomic layers [4] | Top few atomic layers (surface-sensitive due to grazing incidence) [1] |

Quantitative Structural Analysis

The most sophisticated application of LEED is the determination of precise atomic positions through quantitative I-V analysis. This process involves:

Multiple Scattering Calculations: Unlike the kinematic (single-scattering) theory adequate for X-ray diffraction, LEED requires dynamic (multiple-scattering) theory due to strong electron-matter interactions. Computational methods simulate the multiple scattering processes to generate theoretical I-V curves for trial structures [2] [4].

R-Factor Optimization: The trial structure is iteratively refined by comparing theoretical and experimental I-V curves using reliability factors (R-factors) as quantitative measures of goodness of fit. The structure yielding the lowest R-factor is accepted as the correct surface structure [4].

Precision and Limitations: Modern quantitative LEED can determine atomic positions with precisions of ±0.01-0.05 Å. However, the technique requires considerable computational resources and expertise in multiple-scattering calculations, making it one of the more challenging but powerful methods in surface structure analysis [4].

LEED remains an indispensable technique in surface science nearly a century after its initial discovery. Its enduring value lies in its direct visualization of surface periodicity and its ability to provide quantitative atomic-scale structural information through I-V analysis. The technique's extreme surface sensitivity, combined with the relatively straightforward interpretation of diffraction patterns for qualitative analysis, makes it a fundamental tool for characterizing surface reconstructions, adsorption sites, and thin film structures.

As surface science continues to advance into increasingly complex materials systems, including those with fragile molecular components, specialized approaches like FO-LEED demonstrate the methodology's ongoing evolution. The integration of LEED with complementary techniques such as Auger electron spectroscopy for composition analysis and computational modeling for structural refinement creates a powerful multidisciplinary approach to understanding surface phenomena at the atomic scale. For researchers across materials science, catalysis, and semiconductor physics, LEED provides the fundamental structural foundation upon which functional understanding of surface-dependent processes is built.

Low-Energy Electron Diffraction (LEED) is a premier technique for determining the surface structure of single-crystalline materials. By directing a collimated beam of low-energy electrons (20-200 eV) at a crystalline surface and observing the resulting diffraction pattern, researchers can deduce critical information about surface symmetry, atomic positions, reconstructions, and adsorption sites [1] [2]. The technique's exceptional surface sensitivity stems from the low mean free path of electrons in this energy range, limiting penetration to just a few atomic layers (typically 0.5-2 nm) [2]. This application note details the core components of a modern LEED instrument—the electron gun, sample stage, and fluorescent screen—within the context of surface structure analysis research, providing both fundamental principles and practical protocols for researchers and drug development professionals investigating surface-mediated phenomena.

Core Instrument Components

Electron Gun

The electron gun serves as the source of the primary probe beam in a LEED experiment. Its function is to generate a monochromatic, collimated beam of low-energy electrons directed toward the sample surface.

Operating Principle: Electrons are emitted thermionically from a cathode filament held at a high negative potential (typically -30 to -200 V relative to the sample and grounded components) [2]. These electrons are then accelerated and focused through a series of electrostatic lenses—anodes and apertures—that shape the beam and control its diameter, which typically ranges from 0.1 to 0.5 mm [2]. The low kinetic energy of the electrons (20-200 eV) corresponds to a de Broglie wavelength comparable to atomic spacings in solids (approximately 0.87 to 2.7 Ångströms), making them ideal for diffraction from crystalline surfaces [1].

Table 1: Key Operational Parameters of a LEED Electron Gun

| Parameter | Typical Range | Functional Significance |

|---|---|---|

| Electron Energy | 20 - 200 eV | Determines electron wavelength and surface penetration depth [1] [2] |

| Beam Current | Variable (nA-μA) | Controls diffraction spot intensity; must be optimized to prevent surface damage |

| Beam Diameter | 0.1 - 0.5 mm | Defines spatial resolution and area of analysis on the sample surface [2] |

| Energy Spread | < 0.5 eV | Affects sharpness and resolution of diffraction features |

| Filament Material | Tungsten or Lanthanum Hexaboride (LaB₆) | Determines electron emission efficiency and operational lifetime |

Sample Stage

The sample stage is a critical component responsible for presenting a pristine, well-oriented surface to the electron beam under ultra-high vacuum (UHV) conditions.

Operating Principle: The sample, typically a single crystal of the material under investigation, must be meticulously prepared and aligned. The stage must allow for precise manipulation, including heating, cooling, and rotation, to facilitate cleaning and alignment procedures [2]. Maintaining an UHV environment (with a residual gas pressure below 10⁻⁷ Pa) is paramount to preserve the cleanliness of the prepared surface for the duration of the experiment, preventing contamination by gas adsorption [2].

Table 2: Sample Stage Specifications and Preparation Requirements

| Feature/Specification | Description/Requirement |

|---|---|

| Vacuum Environment | Ultra-High Vacuum (UHV), < 10⁻⁷ Pa [2] |

| Sample Temperature Range | Cryogenic (e.g., 100 K) to High-Temperature (e.g., 1300 K+) |

| Manipulation Degrees of Freedom | X, Y, Z translation; tilt and rotation for alignment |

| Standard Sample Size | Several mm² to 1 cm², with specific surface orientation |

| In-situ Cleaning Methods | Ion sputtering (e.g., Ar⁺), annealing, chemical treatments (oxidation/reduction) [2] |

| Surface Preparation Goal | Atomically clean, well-ordered, and flat surface terrace |

Fluorescent Screen & Detection System

The fluorescent screen visualizes the elastically backscattered, diffracted electrons, converting them into a visible diffraction pattern that reveals the symmetry of the surface structure.

Operating Principle: Electrons that are elastically scattered from the sample surface pass through a series of hemispherical grids that act as a high-pass filter. These grids are biased to repel inelastically scattered electrons (which have lost energy), allowing only the elastically scattered ones to reach the positively biased (several kV) fluorescent screen [1] [2]. Upon striking the screen, these high-energy electrons cause fluorescence, creating a pattern of bright spots against a dark background. This pattern is a direct real-space representation of the reciprocal lattice of the surface structure. Modern systems use CCD or CMOS cameras to digitally record the pattern for further analysis [2].

Table 3: Fluorescent Screen and Detection System Characteristics

| Component/Parameter | Characteristics and Function |

|---|---|

| Screen Type | Hemispherical phosphor-coated (e.g., Zinc Sulfide) screen [2] |

| Post-Acceleration Voltage | +3 to +7 kV (for enhanced visibility and detection) [2] |

| Grid System | 3 or 4 concentric hemispherical grids for filtering and field control [2] |

| Primary Function | Visualize diffraction pattern and filter out inelastically scattered electrons |

| Modern Detection | CCD/CMOS cameras or position-sensitive delay-line detectors [2] |

| Measurable Data | Spot positions (for symmetry), spot intensities (for I-V analysis) [1] |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Materials

Successful LEED analysis requires more than just the core instrument; it depends on a suite of high-purity materials and preparation tools.

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for LEED Analysis

| Item/Category | Specific Examples & Functions |

|---|---|

| Single Crystal Substrates | Pt(111), Au(110), Si(100), Cu(111); provide the well-ordered surface for study. |

| Sputtering Gas | Research-grade (99.999%) Argon; used for ion sputtering to clean crystal surfaces [2]. |

| Calibration Samples | Ni(111), Highly Oriented Pyrolytic Graphite (HOPG); used for instrument alignment and verification. |

| Adsorbate Gases | Carbon Monoxide (CO), Oxygen (O₂), Ethylene (C₂H₄); for adsorption and surface reaction studies. |

| Sample Mounting Materials | High-purity Tantalum or Molybdenum wires; used for spot-welding samples for heating and electrical contact. |

| Filaments & Emitters | Tungsten (W) wire, Lanthanum Hexaboride (LaB₆) crystals; electron sources for the gun. |

Experimental Protocols & Methodologies

Protocol 1: Sample Preparation and Loading

Objective: To introduce a sample into the UHV chamber and achieve an atomically clean and well-ordered surface.

- Ex-situ Preparation: Cut and polish the single crystal to the desired crystallographic orientation (e.g., (100), (111)), verified by X-ray diffraction (e.g., Laue back-reflection) [2].

- UHV Chamber Introduction: Mount the sample on the manipulator stage using high-temperature compatible wires (e.g., Ta). Outgas the sample by gently heating to a moderate temperature (e.g., 600 K) for several hours to desorb water vapor and other volatile contaminants.

- Sputter-Etch Cleaning: Expose the sample surface to a beam of inert gas ions (typically Ar⁺ at 0.5 - 2 keV) for a set duration (e.g., 15-60 minutes). This process physically removes the top contaminated layers.

- Thermal Annealing: Following sputtering, anneal the sample at a high temperature (specific to the material, e.g., 1000 K for metals) for several minutes. This step allows surface atoms to migrate and reform a well-ordered, crystalline structure with large, flat terraces [2].

- Cleanliness Verification: Check surface cleanliness using a complementary technique such as Auger Electron Spectroscopy (AES), which can detect trace elemental contaminants [2].

Protocol 2: LEED Instrument Operation and Data Acquisition

Objective: To obtain a qualitative diffraction pattern for surface symmetry analysis and acquire quantitative I-V curves for structural determination.

Part A: Qualitative Pattern Acquisition

- System Check: Ensure UHV conditions are maintained. Verify the electron gun and high-voltage supplies for the screen are operational.

- Beam Alignment: Align the electron gun to ensure the beam is incident perpendicularly onto the sample surface.

- Pattern Observation: Set the electron energy to a standard value (e.g., 100 eV). Gradually increase the beam current until a clear diffraction pattern of bright spots appears on the fluorescent screen.

- Pattern Recording: Use a CCD camera to capture the diffraction pattern. Vary the incident electron energy; as energy changes, the diffraction spots will move radially, but the underlying symmetry of the pattern remains constant, confirming the surface periodicity [1].

Part B: Quantitative I-V Curve Acquisition

- Spot Selection: Identify a specific diffraction spot of interest for I-V analysis.

- Intensity vs. Energy Scan: Ramp the incident electron beam energy smoothly over a wide range (e.g., 50 to 300 eV). Simultaneously, record the intensity of the selected diffraction spot using a photometer or Faraday cup.

- Data Collection: Repeat the intensity measurement for all diffraction spots of interest. The resulting plots of intensity versus beam energy (I-V curves) are unique fingerprints of the atomic structure [1] [2].

- Structural Analysis: Compare the experimental I-V curves to theoretical curves generated by multiple-scattering calculations for trial structures. The model that provides the best agreement (e.g., lowest R-factor) reveals the precise atomic positions at the surface [1] [2].

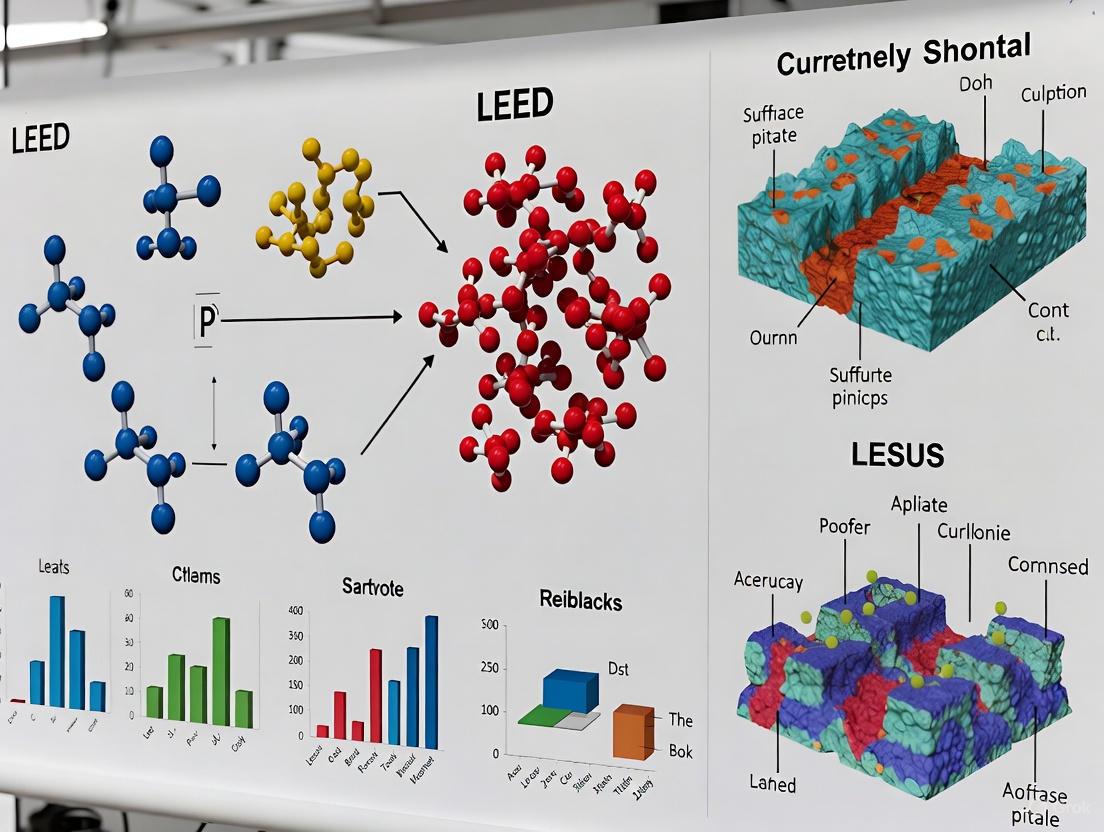

Workflow Visualization

Low-Energy Electron Diffraction (LEED) serves as a fundamental technique in surface science for determining the atomic-scale structure of crystalline surfaces. The core physics of the technique hinges on the wave nature of low-energy electrons (typically 20-200 eV) and their strong interaction with the Coulomb potential of atomic nuclei in the topmost material layers [1]. This strong interaction, coupled with the low penetration depth of these electrons, makes LEED exceptionally sensitive to the top few atomic layers, unlike X-ray diffraction which probes the bulk crystal structure [1]. The process involves directing a collimated beam of these electrons onto a well-ordered sample surface in ultra-high vacuum (UHV), resulting in a diffraction pattern of spots on a fluorescent screen that reveals the symmetry and periodicity of the surface structure [1]. This application note details the protocols for LEED analysis, framed within ongoing research aimed at refining the accuracy and applicability of surface structure determination.

Theoretical Background & Physics of Interaction

The interaction of low-energy electrons with a surface is governed by quantum mechanical scattering. The electrons possess de Broglie wavelengths between approximately 0.87 and 2.7 Ångströms, which is comparable to the interatomic distances in solids, making them ideal for diffraction [1]. When the electron beam strikes the surface, the electrons can undergo various interaction processes. They may be absorbed or scattered inelastically, exciting atomic electrons (leading to Auger electron emission), collective electron gas oscillations (plasmons), or lattice vibrations (phonons) [1]. However, for diffraction, the key process is elastic scattering.

In elastic scattering, electrons are deflected by the atomic nuclei without a net loss of energy. The elastically scattered electron waves from the periodic array of surface atoms interfere with each other. Constructive interference occurs only at specific angles determined by the surface lattice geometry and the electron wavelength, according to the Bragg condition. This results in a backscattered diffraction pattern of distinct spots, with each spot corresponding to a different diffraction beam or Fourier component of the surface structure [1]. The shallow penetration depth—a consequence of high inelastic scattering cross-sections at these energies—is what confines the probing to the top atomic layers and underpins the exceptional surface sensitivity of LEED.

Table 1: Key Characteristics of Low-Energy Electrons in LEED

| Parameter | Typical Range | Significance in Surface Probing |

|---|---|---|

| Electron Energy | 20 - 200 eV | Determines the electron wavelength; must be comparable to atomic spacing for diffraction [1]. |

| Electron Wavelength | 0.87 - 2.7 Å | Similar to interatomic distances, enabling diffraction from crystal lattices [1]. |

| Penetration Depth | A few atomic layers | Confines the signal to the surface, making the technique highly surface-sensitive [1]. |

| Inner Potential (Imaginary Part, V₀ᵢ) | -3.5 to -6 eV | Describes inelastic scattering and determines the natural energy width of diffraction features [5]. |

LEED Experimental Protocol: I(V) Analysis

Quantitative LEED, or LEED I(V), involves measuring the intensity of diffraction spots as a function of the incident electron beam energy to extract precise atomic positions. The following protocol outlines the key steps.

Sample Preparation and System Setup

- UHV Environment: The experiment must be conducted in an ultra-high vacuum chamber (base pressure typically < 10⁻¹⁰ mbar) to prevent surface contamination by adsorbates from the residual gas.

- Sample Mounting: The single-crystalline sample is mounted on a manipulator capable of precise multi-axis positioning (X, Y, Z, rotation, tilt) to align the surface normal with the electron gun.

- Surface Cleaning: The sample surface must be atomically clean and well-ordered. Common cleaning procedures include repeated cycles of sputtering with inert gas ions (e.g., Ar⁺) followed by thermal annealing to restore crystallinity.

- System Calibration: The electron gun is calibrated to ensure accurate energy emission in the 20-200 eV range. The fluorescent screen and detector (e.g., a charge-coupled device camera) are checked for uniform response [1].

Data Acquisition Workflow

- Alignment: Align the sample so the electron beam hits the surface at normal (or a known) incidence.

- Pattern Observation: Observe the diffraction pattern on the fluorescent screen. A sharp, bright, and low-background pattern indicates a clean, well-ordered surface.

- I(V) Curve Measurement:

- Select a diffraction spot of interest for intensity measurement.

- Ramp the electron acceleration voltage (and thus energy E) in small increments (typically 1-5 eV) over the desired range.

- At each energy step, record the integrated intensity,

I, of the selected spot using a Faraday cup or, more commonly, a digital camera system. - Correct the measured intensities for background contribution.

- Repeat this process for multiple diffraction beams to gather a comprehensive data set for structural analysis [5].

Data Analysis and Structure Determination

The core of quantitative LEED is comparing experimental I(V) curves with those calculated from trial structure models.

- Theoretical Calculation: A theoretical model of the surface structure is created, specifying atom types and positions. Multiple scattering (dynamical) calculations are performed to compute theoretical

I(V)curves for this model. These calculations account for the inner potential,V₀ᵢ[5]. - Reliability Factor (R-factor) Comparison: The agreement between experimental and calculated

I(V)curves is quantified using a reliability factor (R-factor). Pendry's R-factor (R_P) is a common metric, though newer factors likeR_Shave been developed to address its sensitivity to noise and intensity offsets [5]. - Structural Optimization: The structural parameters in the theoretical model (e.g., interlayer spacings, adsorption sites, vibrational amplitudes) are systematically varied. The model that produces the lowest R-factor is accepted as the best-fit structure of the surface [5].

Diagram 1: LEED I(V) analysis workflow.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Successful LEED analysis requires a suite of specialized equipment and materials, typically integrated into a single UHV system.

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for LEED Analysis

| Item | Function / Relevance |

|---|---|

| LEED Optique | The core apparatus, comprising an electron gun, a set of biased grids, and a fluorescent screen. The grids filter inelastically scattered electrons, allowing only elastically scattered ones to form the diffraction pattern [1]. |

| UHV System | Provides the necessary pristine environment (pressure < 10⁻¹⁰ mbar) to maintain an atomically clean surface for the duration of the experiment, free from contaminant adsorption. |

| Sample Manipulator | Allows precise positioning and thermal treatment (heating and cooling) of the sample crystal for alignment, cleaning, and phase transition studies. |

| I(V) Curve Acquisition Software | Controls the electron gun voltage and synchronizes it with the intensity recording from the detector (e.g., CCD camera) to automate data collection. |

| Multiple Scattering Simulation Software | Performs the computationally intensive theoretical calculations of I(V) curves for trial structures, which are essential for quantitative structural analysis [5]. |

| Sputtering Ion Gun | Used for sample cleaning by bombarding the surface with inert gas ions (e.g., Ar⁺) to remove contaminated surface layers. |

Advanced Quantitative Analysis: Reliability Factors

The precision of a LEED structure determination hinges on the choice of the reliability factor (R-factor) used to gauge the agreement between experiment and theory.

R_P is based on a comparison of the logarithmic derivatives of the intensity, which makes it less sensitive to slow, smooth variations in experimental intensity scales. However, it can be a noisy target for optimization and is sensitive to small intensity offsets [5]. Recent research has focused on developing improved R-factors, such as R_S, which is designed as a direct replacement for R_P but provides a smoother optimization landscape and avoids some of its pathological behaviors, potentially leading to more robust and reliable structure determination [5].

Table 3: Comparison of Common LEED Reliability (R) Factors

| R-factor | Basis of Calculation | Advantages | Disadvantages |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pendry's R_P | Logarithmic derivative of I(E) [5] |

Less sensitive to slow intensity scale variations; well-established. | Noisy optimization target; sensitive to small intensity offsets [5]. |

| Zanazzi-Jona R_ZJ | First and second derivatives of I(E) [5] |

Puts increased weight on regions of minima and maxima. | Very sensitive to noise in data and numerical errors in calculations [5]. |

| Modified R_S | Addresses shortcomings of R_P [5] |

Smoother target for optimization; avoids pathologies of R_P. |

Newer factor, less historical data on performance. |

Comparative Techniques and Application Perspectives

While LEED is a powerful tool for surface structure analysis of bulk materials, other diffraction techniques offer complementary information. Reflection High-Energy Electron Diffraction (RHEED) uses high-energy electrons (8-20 keV) at a grazing incidence angle. This geometry makes RHEED particularly well-suited for in-situ monitoring of thin film growth and epitaxy, such as in Molecular Beam Epitaxy (MBE) systems, as the grazing incidence does not obstruct the path of incoming evaporant fluxes [1].

The principles of electron diffraction are also finding transformative applications beyond traditional surface physics. The ability of electron diffraction to perform nanocrystallography on miniscule crystals is a disruptive innovation, opening new perspectives for determining the structures of organic compounds, including active pharmaceutical ingredients (APIs), which are often difficult to crystallize into large enough crystals for X-ray diffraction [6].

Diagram 2: LEED vs. RHEED comparison.

Electron Wavelength, Elastic Scattering, and Constructive Interference

Fundamental Concepts

This section details the core physical principles that underpin Low-Energy Electron Diffraction (LEED), focusing on the wave nature of electrons, their interaction with crystalline surfaces, and how these interactions are measured to reveal atomic surface structures.

Electron Wavelength

The wave-like behavior of electrons is fundamental to diffraction techniques. According to de Broglie's hypothesis, all moving particles exhibit wave properties, with a wavelength inversely proportional to their momentum [7] [8]. For an electron, this wavelength is given by:

λ = h / p

where h is Planck's constant (approximately 6.626 × 10⁻³⁴ J·s) and p is the electron's momentum [7] [8]. For electrons accelerated by an electric potential, this relationship can be expressed in a more practical form. The resulting de Broglie wavelength dictates the length scale at which the electron's wave-like properties become significant and is crucial for achieving diffraction from atomic lattices [8].

Table: Electron Wavelength and Energy Parameters in LEED

| Parameter | Typical Range in LEED | Description & Significance |

|---|---|---|

| Electron Energy | 20 - 200 eV [1] | Determines the electron's penetration depth; low energies ensure surface sensitivity. |

| De Broglie Wavelength (λ) | 0.87 - 2.7 Ångströms [1] | Comparable to atomic spacings in solids, enabling diffraction. |

| Planck's Constant (h) | 6.626 × 10⁻³⁴ J·s [7] | Fundamental constant relating a particle's energy to its wave frequency. |

Elastic Scattering

Elastic scattering is the process wherein incident electrons are deflected by the electrostatic potential of atoms without a net transfer of energy to the sample [9] [10]. The internal energy states of the particles involved remain unchanged, and in the non-relativistic case, the total kinetic energy of the system is conserved [9]. In the context of LEED, the primary form of elastic scattering is the diffraction of electrons by the Coulomb potential of atoms in the crystalline surface [9] [1]. This interaction is strongly influenced by the atomic number (Z) of the target atoms and the energy of the incident electrons, described quantum mechanically by scattering cross-sections [10]. For low-energy electrons, the scattering process is highly sensitive to the top few atomic layers, as the electrons lack the energy to penetrate deeply into the bulk material [1].

Constructive Interference and Bragg's Law

Constructive interference is the phenomenon that gives rise to the distinct diffraction patterns observed in LEED. When the elastically scattered electron waves from a periodic array of surface atoms are in phase, they reinforce each other [1]. This constructive interference occurs only at specific angles, satisfying the conditions set by the crystal's geometry. For a crystalline surface, this requires that the path difference between waves scattered from adjacent atoms is equal to an integer multiple of the electron's wavelength. This condition is encapsulated in Bragg's Law, which, for a surface lattice, can be stated as the requirement for the scattering vector to equal a reciprocal lattice vector. The fulfillment of this condition results in the appearance of sharp, bright spots on the LEED detector screen, where each spot corresponds to a specific set of crystal planes from which constructive interference has occurred [1].

Application in LEED Surface Structure Analysis

Low-Energy Electron Diffraction (LEED) is a premier technique for determining the atomic structure of crystalline surfaces. It leverages the concepts of electron wavelength, elastic scattering, and constructive interference to provide detailed information about surface symmetry, reconstruction, and adsorption [1]. The process involves directing a collimated beam of low-energy electrons (typically 30-200 eV) onto a well-ordered sample surface in an ultra-high vacuum environment. The electrons, with wavelengths comparable to interatomic distances, are elastically scattered by the surface atoms [1]. The resulting pattern of constructive interference is observed as distinct spots on a fluorescent screen, providing a direct real-space mapping of the surface's reciprocal lattice [1].

Experimental Protocol: LEED Surface Analysis

Objective: To determine the surface structure and symmetry of a single-crystalline sample.

Materials and Reagents: Table: Essential Research Reagents and Equipment for LEED

| Item Name | Function / Role in Experiment |

|---|---|

| UHV Chamber | Provides a contamination-free environment (pressure < 10⁻¹⁰ mbar) to maintain surface cleanliness. |

| Electron Gun | Generates a monochromatic, focused beam of low-energy electrons (20-200 eV) [1]. |

| Single-Crystal Sample | The material under investigation, with a well-defined and clean surface. |

| Sample Holder & Manipulator | Holds the sample and allows for precise positioning, heating, and cooling. |

| Fluorescent Screen | Detects elastically scattered electrons, displaying the diffraction pattern as bright spots [1]. |

| CCD Camera | Records the position and intensity of the diffraction spots for further analysis. |

Procedure:

- Sample Preparation: Introduce the sample into the UHV chamber. Clean the surface in-situ using cycles of ion sputtering (e.g., with Ar⁺ ions) and thermal annealing until no contaminants are detected and a sharp diffraction pattern is observed.

- System Calibration: Calibrate the electron gun to ensure the accuracy of the incident electron energy. This may involve using a standard sample with a known surface structure.

- Data Acquisition:

a. Set the incident electron energy to a value within the 50-150 eV range.

b. Observe the diffraction pattern on the fluorescent screen. The pattern should consist of a regular array of bright spots corresponding to constructive interference from the surface lattice [1].

c. For qualitative analysis (surface symmetry): Record the diffraction pattern at several energies. Analyze the spot positions to determine the size and symmetry of the surface unit cell. The presence of additional spots, or a "superlattice," indicates surface reconstruction or adsorbed species [1].

d. For quantitative analysis (atomic positions): For multiple diffraction spots, record the spot intensity (

I) as a function of the incident beam energy (V) to generate I-V curves [1]. This is a critical step for determining precise atomic coordinates. - Data Analysis: a. Qualitative: Compare the observed pattern geometry to the known bulk termination to identify surface reconstruction (e.g., (2x1) reconstruction). b. Quantitative: Compare the experimental I-V curves to theoretical curves generated by multiple-scattering calculations for trial structures. The trial structure that produces the best fit to the experimental data is accepted as the correct surface model [1].

Data Presentation and Analysis

The primary quantitative data in LEED is the set of I-V curves, which are used to refine the atomic structure of the surface. The following table summarizes key parameters and a typical data structure for analysis.

Table: Key Parameters for LEED I-V Curve Data Collection and Analysis

| Beam Index (h,k) | Incident Energy Range (eV) | Data Points | Primary Sensitivity | Remarks |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (0,0) | 50 - 300 | 200 | Topmost layer spacing, overall potential | Strongest beam; used for initial model fitting. |

| (1,0) | 80 - 250 | 150 | Lateral atom positions, bond lengths | Sensitive to reconstruction. |

| (1,1) | 100 - 300 | 150 | Surface rumpling, multilayer relaxation | |

| (0,1) | 80 - 250 | 150 | Lateral atom positions, bond lengths | Should be equivalent to (1,0) for symmetric surfaces. |

Advanced Protocol: Quantitative I-V Curve Analysis

Objective: To derive precise atomic coordinates (positions and layer spacings) from experimental LEED data.

Procedure:

- Data Acquisition: For a set of relevant diffraction beams (e.g., (0,0), (1,0), (1,1)), measure the intensity of each beam with high precision over a wide energy range (typically 50-400 eV) in steps of 1-5 eV to generate dense I-V curves [1].

- Theory/Calculation: a. Model Building: Propose a trial surface structure model based on symmetry and chemical intuition. This model includes atomic types, positions, and layer spacings. b. Multiple Scattering Calculation: Use specialized software (e.g., tensor LEED packages) to calculate the theoretical I-V curves for the trial structure. This calculation must account for multiple elastic scattering events of the electrons within the surface layers, a crucial factor for low-energy electrons [1]. c. Pendry R-Factor (R_P) Calculation: Quantitatively compare the theoretical and experimental I-V curves using a reliability factor (R-factor), such as the Pendry R-factor. The R-factor is a measure of the agreement between the two curves, with a lower value indicating better agreement.

- Structural Refinement: a. Systematically vary the structural parameters in the trial model (e.g., bond lengths, interlayer relaxations, adsorption heights). b. Recalculate the theoretical I-V curves and R-factor for each new configuration. c. Iterate this process until the R-factor is minimized. The structural model at the R-factor minimum is considered the best representation of the true surface structure [1].

Low-Energy Electron Diffraction (LEED) is a foundational technique in surface science for determining the atomic-scale structure of crystalline surfaces [2]. The technique operates on the principle of directing a collimated beam of low-energy electrons (typically 20-500 eV) at a well-ordered single-crystalline sample and observing the resulting diffraction pattern of elastically scattered electrons on a fluorescent screen [1] [11]. The power of LEED lies in its exceptional surface sensitivity; due to the strong interaction between low-energy electrons and solid matter, the inelastic mean free path of these electrons is minimal, resulting in a sampling depth of only a few atomic layers [12] [2]. This makes LEED uniquely suited for investigating surface-specific phenomena that are inaccessible to bulk-sensitive techniques like X-ray diffraction.

This application note details how the analysis of spot positions in LEED diffraction patterns reveals surface symmetry, framed within the broader context of surface structure analysis research. We provide comprehensive protocols for both qualitative symmetry determination and quantitative intensity analysis, enabling researchers to extract maximum structural information from their samples. The ability to precisely characterize surface structure is paramount across numerous fields, from semiconductor manufacturing where interface quality dictates device performance, to heterogeneous catalysis where reaction pathways are intimately tied to surface atomic arrangement [1].

Theoretical Foundations of Electron Diffraction at Surfaces

Electron Wavelength and Energy Relationship

The fundamental condition for observing diffraction is that the probing radiation has a wavelength comparable to the interatomic spacings within the sample. For LEED, this relationship between the electron kinetic energy and its de Broglie wavelength is derived from quantum mechanics [3]:

[ \lambda = \frac{h}{\sqrt{2m_e e V}} \approx \sqrt{\frac{1.5}{E \mathrm{[eV]}}} \quad \text{[nm]} ]

where (h) is Planck's constant, (m_e) is the electron mass, (e) is the electron charge, and (V) is the acceleration voltage, with the electron energy (E = eV) expressed in electron volts [2] [3].

Table: Electron Wavelength vs. Energy in the LEED Range

| Electron Energy (eV) | Electron Wavelength (Å) | Comparison to Atomic Spacings |

|---|---|---|

| 20 | 2.74 | Larger than typical lattice spacing |

| 50 | 1.73 | Comparable to lattice spacing |

| 100 | 1.23 | Slightly smaller than lattice spacing |

| 200 | 0.87 | Significantly smaller than lattice spacing |

As the table illustrates, the standard LEED energy range (20-200 eV) produces electron wavelengths between approximately 0.87 and 2.74 Ångströms, which is precisely the scale of interatomic distances in solids (typically 2-3 Å), thereby satisfying the fundamental condition for diffraction [1].

The LEED Pattern as a Direct Representation of Reciprocal Space

When a low-energy electron beam is incident normally on a crystalline surface, the elastically scattered electrons interfere constructively in specific directions determined by the surface periodicity [3]. The condition for constructive interference is described by the Bragg condition in one dimension:

[ a \sin \theta = n \lambda ]

where (a) is the atomic spacing, (\theta) is the scattering angle, (n) is an integer, and (\lambda) is the electron wavelength [3]. In two dimensions, this generalizes to the Laue conditions, which state that constructive interference occurs only when the change in the electron wave vector parallel to the surface equals a vector of the two-dimensional reciprocal lattice [2].

Critically, the diffraction pattern observed on the LEED screen is a direct image of the reciprocal lattice of the surface structure, not the real-space lattice. The positions of the diffraction spots immediately reveal the symmetry and dimensions of the surface unit cell. Integral-order spots correspond to the substrate periodicity, while additional spots (fractional-order spots) indicate the presence of a reconstructed surface or an ordered adsorbate overlayer [12] [2].

Figure 1: The pathway from real-space structure to observed LEED pattern involves scattering and Fourier transformation.

The LEED Instrument: Experimental Setup and Components

A modern LEED system requires an ultra-high vacuum (UHV) environment, typically with a base pressure below 10⁻⁹ mbar, to maintain surface cleanliness for the duration of the experiment [2]. The key components of the LEED instrument include:

Core Instrument Components

- Electron Gun: Produces a monochromatic, collimated beam of electrons with energies tunable between approximately 20-500 eV. The gun consists of a cathode filament held at a negative potential, with electrostatic lenses for beam focusing and alignment [2] [11].

- Sample Manipulator: Holds the single-crystal sample in a precise orientation, often with capabilities for heating, cooling, and rotation about multiple axes. The sample must be prepared with an exceptionally well-ordered surface through cycles of sputtering and annealing [2].

- Energy Filter (Retarding Field Analyzer): Typically composed of three or four concentric hemispherical grids. The first grid is at ground potential to create a field-free region, while subsequent grids are biased to reject inelastically scattered electrons, allowing only elastically scattered electrons to pass through to the detector [2] [3].

- Detection System: Traditionally a fluorescent screen where the diffraction pattern is directly visible, often coupled with a CCD/CMOS camera for digital recording. More advanced systems use position-sensitive electron detectors for quantitative intensity measurements [2].

Table: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for LEED Analysis

| Component/Reagent | Function/Specification | Critical Parameters |

|---|---|---|

| Single Crystal Samples | Provides well-ordered surface for diffraction | Surface orientation, purity (>99.99%) |

| Sputtering Ion Source | Cleans surface by removing contaminants | Ar⁺ or Ne⁺ ions, 0.5-5 keV energy |

| Sample Heating Apparatus | Anneals surface to restore crystallinity | Capable of 300-1500 K, precise control |

| Liquid Nitrogen Cryostat | Cools sample for temperature-dependent studies | Capable of cooling to 80 K or lower |

| Gas Dosing System | Introduces controlled amounts of adsorbates | Precision leak valve, pressure measurement |

Figure 2: Schematic diagram of key LEED instrument components operating in ultra-high vacuum.

Qualitative Analysis: From Diffraction Spots to Surface Symmetry

Protocol: Interpretation of Spot Patterns for Symmetry Determination

Objective: To determine the symmetry and dimensions of the surface unit cell from the LEED diffraction pattern.

Materials and Equipment:

- LEED instrument with UHV capability

- Well-prepared single crystal sample

- Digital camera for pattern recording

- Standard reference materials for calibration

Procedure:

Sample Preparation and Mounting

- Clean the single crystal surface through repeated cycles of argon ion sputtering (1-3 keV, 5-30 minutes) followed by thermal annealing at temperatures appropriate for the material (typically 300-1000°C) until a sharp diffraction pattern is obtained [2].

- Verify surface cleanliness using complementary techniques such as Auger Electron Spectroscopy (AES) if available [2].

Pattern Acquisition

- Set the electron gun to an intermediate energy (typically 80-150 eV) where the diffraction spots are clearly visible and well-distributed across the screen [12].

- Adjust the beam current to 0.1-1 μA to ensure good spot intensity without causing sample charging, particularly important for insulating samples [12].

- Record the diffraction pattern using a digital camera, ensuring the entire screen is in focus and the spot intensities are not saturated.

Spot Position Analysis

- Identify the (0,0) specular reflection at the center of the pattern.

- Measure the positions of all diffraction spots relative to the center spot.

- Identify the smallest set of non-collinear spots closest to the center; these represent the fundamental reciprocal lattice vectors.

- Determine the symmetry of the pattern by identifying rotational and mirror symmetries.

Unit Cell Determination

- Calculate the ratios of spot spacings to determine the relative dimensions of the surface unit cell compared to the substrate.

- Identify any additional (fractional-order) spots that indicate surface reconstruction or adsorbate superstructures.

- Classify the pattern according to standard surface notation (e.g., (1×1), (2×2), c(2×2), (√3×√3)R30°, etc.) [2] [3].

Interpretation Guidelines:

- A (1×1) pattern indicates the surface unit cell is identical to the bulk-terminated structure [2].

- The presence of fractional-order spots indicates a surface reconstruction or ordered adsorbate layer with a larger unit cell than the substrate [12].

- Diffuse spots or high background intensity suggests disorder or small domain sizes in the surface structure [12].

- For adsorbate systems, the symmetry and size of the superlattice spots reveal the adsorbate unit cell dimensions and its rotational alignment with respect to the substrate [2].

Case Study: CO₂ Adsorption on KCl(100)

Research demonstrates the power of qualitative LEED analysis in studying adsorption phenomena. When a clean KCl(100) surface at 81 K is exposed to CO₂, the initial diffraction pattern shows reduced intensity in the integral order spots ((1,0), (1,1), (2,0)) and a diffuse background with intensity maxima at (½,½) positions, indicating the presence of admolecules without long-range order [12]. After cooling to 25 K without further exposure, distinct fractional-order diffraction peaks appear at (½,½) and (1½,½), confirming the formation of a CO₂ adlayer with (2×2) symmetry and long-range order [12]. This temperature-dependent structural transition showcases how LEED can track the evolution of surface ordering in response to experimental parameters.

Quantitative LEED I-V Analysis: From Intensities to Atomic Positions

Protocol: Acquisition and Analysis of I-V Curves

Objective: To determine precise atomic positions on the surface by measuring and analyzing diffracted beam intensities as a function of incident electron energy.

Materials and Equipment:

- LEED system with current-measuring capability or position-sensitive detector

- Computer-controlled electron gun and data acquisition system

- Computational software for dynamical LEED calculations

Procedure:

Data Acquisition

- Select a set of diffracted beams for analysis (typically 5-15 beams including both integral and fractional order spots).

- For each beam, sweep the incident electron energy in small increments (1-2 eV) over a range typically from 30 to 300-500 eV.

- At each energy step, measure the intensity of the diffracted beam using a Faraday cup, photometer, or position-sensitive detector [2].

- Normalize intensities to account for variations in incident beam current.

Data Processing

- Smooth the I-V curves to reduce noise while preserving features.

- Apply background subtraction to remove inelastic background contributions.

- Normalize curves for comparison with theoretical calculations.

Theoretical Modeling and Comparison

- Create an initial structural model based on available information (bulk structure, chemical knowledge, complementary techniques).

- Calculate theoretical I-V curves using dynamical LEED theory that accounts for multiple scattering effects [2].

- Systematically vary structural parameters (interlayer spacings, atomic coordinates, vibrational amplitudes) in the model to find the best agreement with experimental data.

- Quantify agreement using reliability factors (R-factors), with the Pendry R-factor being most common [2].

Critical Considerations:

- Multiple scattering makes LEED analysis complex; kinematic (single-scattering) theory is generally insufficient for quantitative analysis [2].

- A sufficiently large database of I-V curves is essential for reliable structure determination.

- The analysis typically requires comparison of 5-15 beams over energy ranges of 100-500 eV per beam [12].

Figure 3: Iterative workflow for quantitative LEED I-V structure analysis using dynamical theory.

Advanced Applications and Future Directions

LEED continues to evolve as a critical tool for surface structure analysis. Recent research highlights its application to increasingly complex systems, including molecular networks on insulating substrates and disordered surfaces [13]. The technique's particular strength lies in its ability to provide quantitative information about adsorption sites, bond lengths, and structural rearrangements at surfaces.

In semiconductor manufacturing, LEED plays a vital role in quality control by ensuring proper surface ordering and orientation of epitaxial layers [1]. The development of Very-Low-Energy Electron Diffraction (VLEED) in the 0-10 eV range offers enhanced sensitivity to light elements like hydrogen and the surface potential barrier, though with a more limited database [12].

Future advancements in LEED methodology focus on improving computational algorithms for faster and more accurate I-V curve analysis, extending the technique to more complex and disordered systems, and combining LEED with complementary techniques like scanning probe microscopy for comprehensive surface characterization [13] [12]. These developments ensure LEED will remain an indispensable tool in the surface scientist's arsenal, bridging the gap between spot positions and atomic-scale surface structure.

Applying LEED I(V) Analysis: From Theory to Practice in Materials Science

Low-Energy Electron Diffraction (LEED) is a premier technique for determining the surface structure of single-crystalline materials [1]. By directing a collimated beam of low-energy electrons (20-200 eV) onto a well-ordered crystalline surface and analyzing the resulting diffraction pattern, researchers can deduce the symmetry and atomic arrangement of the topmost layers [1]. The technique's extreme surface sensitivity, owing to the short inelastic mean free path of low-energy electrons, makes it indispensable for studying surface reconstructions, adsorption sites, and thin films—critical processes in catalyst development and material science [1] [4].

The following workflow outlines the primary stages of a LEED experiment, from sample preparation to data interpretation:

Experimental Setup & Apparatus

The LEED Instrument

A standard LEED apparatus consists of several key components housed within an ultra-high vacuum (UHV) chamber to maintain surface purity [1].

Core Components:

- Electron Gun: Generates a monochromatic beam of low-energy electrons (typically 20-200 eV) [1]. The gun must be precisely calibrated to ensure the incident electron wavelength is comparable to interatomic distances (0.87 - 2.7 Ångströms) [1].

- Sample Holder and Manipulator: Positions the single-crystal sample in the path of the electron beam. It allows for precise control over polar and azimuthal angles and often includes heating and cooling capabilities. Liquid helium cooling is used to minimize thermal desorption of weakly bonded species and reduce atomic thermal vibrations [4].

- Fluorescent Screen or Detector: A concentric hemispherical grid system that allows elastically scattered electrons to pass through, striking a phosphorescent screen. This creates a visible diffraction pattern of distinct spots [1].

- Image Capture System: Modern systems use fibre-optic coupling to transfer the diffraction pattern to a high-sensitivity, slow-scan CCD camera. This is particularly crucial for beam-sensitive samples, as it allows operation at very low beam currents (~1 nA) to minimize damage [4].

Research Reagent Solutions & Essential Materials

Table 1: Key Materials and Components for LEED Analysis

| Item | Function/Application | Critical Specifications |

|---|---|---|

| Single-Crystal Samples | Substrate for surface structure analysis. | High-purity, well-oriented, well-ordered surfaces (e.g., Pt(111), Cu(100), TiO₂(110)). |

| Electron Gun Filament | Source of electron beam. | High brightness, stable emission at 20-200 eV energy range. |

| UHV-Compatible Materials | Construction of chamber and sample holder. | Low vapor pressure (e.g., stainless steel, tantalum, copper) to maintain pressure < 10⁻¹⁰ mbar. |

| Liquid Helium/Nitrogen Cryostat | Sample cooling. | Minimizes thermal desorption and reduces thermal vibrations for sharper patterns [4]. |

| Sputtering Ion Gun | In-situ surface cleaning. | Typically uses Ar⁺ ions for sputtering contaminants. |

| Gas Dosing System | Introduction of adsorbates. | Controlled leak valve for precise exposure (Langmuirs) of research gases (e.g., O₂, CO, H₂). |

Step-by-Step Experimental Protocol

Phase I: System Setup & Calibration

Step 1: LEED System Assembly and UHV Establishment

- Mount the single-crystal sample on the UHV-compatible holder using high-temperature adhesives or spot-welding.

- Insert the sample into the UHV chamber and pump down to a base pressure typically below 1x10⁻¹⁰ mbar to prevent surface contamination.

- Verify the operational status of all components: electron gun, fluorescent screen, CCD camera, and sample manipulator.

Step 2: Electron Gun Calibration

- Calibrate the electron gun to emit electrons in the desired energy range of 20-200 eV [1].

- Ensure the beam is focused and aligned perpendicular (or nearly perpendicular) to the sample surface [1].

Phase II: Sample Preparation

Step 3: Surface Cleaning

- Clean the crystal surface in-situ using repeated cycles of noble gas ion sputtering (e.g., Ar⁺) followed by thermal annealing.

- Sputtering removes impurities, while annealing recrystallizes the surface, restoring long-range order.

Step 4: Surface Order Verification

- Direct the low-energy electron beam onto the freshly prepared surface.

- Observe the fluorescent screen for a sharp, high-contrast pattern of distinct diffraction spots, which confirms a well-ordered, clean surface.

Phase III: Data Acquisition

Step 5: Qualitative LEED (Pattern Imaging)

- Capture the diffraction pattern on the fluorescent screen using the CCD camera at a single electron beam energy.

- Record the spot positions and symmetry. This pattern is a direct real-space representation of the reciprocal lattice of the surface structure [1].

Step 6: Quantitative LEED (I-V Curve Measurement)

- For a quantitative structure determination, measure the intensity of multiple diffracted beams as a function of the incident electron beam energy [1] [4].

- Systematically vary the beam energy (e.g., from 30 to 300 eV) and record the intensity of selected diffraction spots using a photometer or the CCD camera.

- Plot the intensity versus voltage for each beam to generate a set of "I-V curves," which serve as the primary experimental data for structural determination [1].

Data Interpretation & Analysis

LEED analysis is a trial-and-error process because the loss of phase information and strong multiple scattering of electrons prevent direct structural calculation [4]. The workflow for data interpretation is as follows:

1. Qualitative Interpretation:

- Analyze the symmetry and spot arrangement of the diffraction pattern. The size and rotational alignment of the surface unit cell can be directly determined from the pattern [1].

- For surfaces with adsorbates, this reveals the size and rotational alignment of the adsorbate's unit cell relative to the substrate [1].

2. Quantitative Analysis (I-V Curve Methodology):

- Propose a Trial Structure: Based on the symmetry from the qualitative analysis and chemical intuition, propose a hypothetical atomic model of the surface [4].

- Theoretical Calculation: Use multiple-scattering theory to simulate the LEED process and calculate theoretical I-V curves for the trial structure. This requires sophisticated computational methods [1] [4].

- Curve Comparison & Refinement (R-Factor Analysis): Compare the theoretical I-V curves with the experimental data using a reliability factor, or "R-factor," which quantifies the goodness of fit [4].

- Iterative Refinement: Systematically adjust the atomic coordinates (e.g., interlayer spacings, adsorption sites) in the trial model and repeat the simulation until the R-factor is minimized. The structure yielding the lowest R-factor is accepted as the correct surface structure [4].

Critical Parameters & Troubleshooting

Table 2: Key Experimental Parameters and Optimization Guidelines

| Parameter | Typical Range | Impact on Data Quality & Troubleshooting |

|---|---|---|

| Beam Energy | 20 - 200 eV [1] | Low Energy: Greater surface sensitivity. High Energy: Deeper penetration. Optimize for sufficient diffraction spot intensity. |

| Beam Current | ~1 nA (low-dose) [4] | High currents can damage delicate surfaces (organics, water ice). Use lowest current that provides measurable signal. |

| Sample Temperature | 30 K (Cryo-cooled) to 1500 K [4] | Cooling: Stabilizes weakly-bonded species, reduces thermal vibrations. Heating: Used for annealing and cleaning. |

| Surface Order | Long-range crystallinity | Diffuse spots or high background indicate poor surface order. Re-clean and anneal the sample. |

| Work Function | Material dependent | Affects the secondary electron background. Account for in quantitative intensity measurements. |

Comparative Techniques: LEED vs. RHEED

Table 3: LEED vs. RHEED for Surface Structure Analysis

| Aspect | LEED | RHEED |

|---|---|---|

| Energy Range | 20 to 200 electron volts (eV) [1] | 8 to 20 kilo electron volts (keV) [1] |

| Incidence Angle | Perpendicular or nearly perpendicular [1] | Grazing incidence (very low angle) [1] |

| Diffraction Pattern | Pattern of distinct spots on a fluorescent screen [1] | Elongated streaks or arcs [1] |

| Primary Applications | Surface structure analysis of bulk materials, surface chemistry and physics [1] | In-situ monitoring of thin film growth and epitaxy (e.g., during MBE) [1] |

| Key Advantage | Direct, intuitive visualization of surface symmetry. | Compatible with simultaneous deposition on the surface. |

In the context of LEED surface structure analysis research, determining the symmetry and precise atomic positions of a material is fundamental. Analytical techniques for characterizing crystalline materials are broadly categorized into qualitative and quantitative methods. Qualitative analysis establishes the presence of specific elements, compounds, or crystalline phases in a sample [14]. In contrast, quantitative analysis determines the precise amount or concentration of these components and refines their exact spatial positions [14]. Within surface science, Low-Energy Electron Diffraction (LEED) is a powerful technique that can be leveraged for both purposes, providing a pathway from initial structural identification to a detailed, quantified surface model [15].

The following table summarizes the core distinctions between these analytical approaches as applied to LEED studies.

Table 1: Core Distinctions Between Qualitative and Quantitative LEED Analysis

| Analytical Feature | Qualitative Phase Analysis | Quantitative Phase Analysis |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Objective | Identify crystalline components and surface symmetries present in the sample. | Determine precise atomic positions and relative abundances of phases. |

| Data Utilized | Peak positions and overall pattern shape in the LEED image or I(V) curve. | Modulated intensities of diffracted beams as a function of incident electron energy (LEED I(V) curves). |

| Comparison Basis | Compares experimental diffraction patterns with known reference patterns or databases. | Compares experimental I(V) curves with theoretical simulations derived from structural models. |

| Key Output | Identification of surface periodicity, symmetry, and possible structural phases. | Refined atomic coordinates, interlayer spacings, and quantitative surface structure. |

Qualitative Phase Identification Techniques

Fundamentals of Phase and Symmetry Identification

The primary goal of qualitative analysis in LEED is the identification of crystalline components and surface symmetries. This process is based on the principle that the arrangement of bright spots in a LEED pattern is a direct fingerprint of the surface periodicity and symmetry [15]. Each bright spot corresponds to a specific angle at which electrons are coherently scattered by the ordered atomic lattice. By analyzing the spatial arrangement of these spots, researchers can determine the surface's unit cell size and symmetry, and identify if the surface has a intended or reconstructed structure [15]. This information is crucial for initial sample characterization and for selecting appropriate models for subsequent quantitative refinement.

Search-Match Analysis and Pattern Recognition

The qualitative identification process often involves a systematic search-match analysis, where the experimental LEED pattern is compared against a library of known patterns [16]. This process includes initial spot identification and background subtraction. Software algorithms can assist in searching for potential matches, which are then ranked based on similarity scores [16]. However, confirming a match requires user expertise to evaluate the suggested patterns, considering potential complications such as multiple domains, impurities, and the presence of underlying substrate patterns. The successful identification of a surface's symmetry through its LEED pattern is the critical first step that enables deeper quantitative investigation.

Quantitative Phase Analysis Methods

Principles of Quantitative Structural Refinement

Quantitative LEED (I-V LEED) moves beyond simple symmetry identification to extract precise information about atomic positions and interlayer spacings. The quantitative information about the surface structure is contained in the modulation of the intensities of the diffracted beams as a function of the incident electron energy, known as LEED I(V) curves [15]. These intensity-energy curves provide precise details about how the scattered electrons interact with the surface's atoms, making them highly sensitive to the exact positions of atoms in the topmost layers [15]. The core principle of quantitative analysis is to computationally simulate I(V) curves for a proposed structural model and iteratively refine the model's parameters to achieve the best possible match with the experimental data.

Intensity Analysis and Structural Optimization

The process of structural optimization involves adjusting the positions of atoms in the theoretical model to better match the experimental I(V) data [15]. Advanced software packages, such as the ViPErLEED package, automate this refinement process. They use sophisticated algorithms to minimize the difference (often measured by an R-factor) between the calculated and experimental curves [15]. This optimization can determine not only the lateral positions of atoms but also crucial vertical relaxations and rippling in the surface layers. The ability to handle complex surfaces and perform calculations efficiently is key to making quantitative LEED analysis more accessible and reducing the potential for human error [15].

Table 2: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for LEED Surface Analysis

| Research Reagent / Material | Function in Analysis |

|---|---|

| High-Purity Single Crystal Sample | Serves as the substrate for surface structure analysis. Must be atomically clean and well-ordered. |

| ViPErLEED Software Package | Performs automated LEED I(V) calculations and structural optimization, minimizing manual labor and potential for errors [15]. |

| Reference Intensity Ratio (RIR) Values | Pre-determined values used in quantitative methods for estimating phase abundance based on peak intensity ratios [16]. |

| Sputtering and Annealing Apparatus | Used for sample preparation to create a clean, atomically flat and well-ordered surface for analysis (e.g., for hematite surfaces) [15]. |

| Atomic Simulation Environment (ASE) | A Python package that provides interfaces for atomistic simulations and can be directly integrated with modern LEED analysis software [15]. |

Experimental Protocols for LEED Surface Analysis

Protocol A: Qualitative Surface Symmetry Determination

This protocol outlines the steps for determining the surface symmetry and identifying potential structural phases using LEED.

- Sample Preparation: Prepare a clean, well-ordered surface. For a metal oxide like hematite, this typically involves cycles of sputtering with argon ions (e.g., at 1 keV for 10-30 minutes) followed by thermal annealing in an oxygen atmosphere (e.g., at 600-700°C for 10-20 minutes) to restore surface order and stoichiometry [15].

- Data Acquisition: Mount the prepared sample in the ultra-high vacuum (UHV) chamber. Align the sample normal with the LEED optics. Acquire a series of LEED patterns across a range of electron energies (e.g., 50 eV to 300 eV). Ensure the patterns are sharp and have low background intensity.

- Pattern Analysis: Visually inspect the LEED patterns. Identify the arrangement of spots and the associated surface Bravais lattice. Measure the spot positions and relative angles to determine the surface unit cell and its symmetry.

- Search-Match: Compare the observed pattern geometry (spot positions and symmetry) against a database of known surface structures for the material under investigation. Consider possible surface reconstructions based on the substrate's bulk termination.

Protocol B: Quantitative Atomic Position Refinement via I(V) Analysis

This protocol details the methodology for extracting precise atomic coordinates from LEED I(V) curves.

- I(V) Curve Acquisition: After qualitative symmetry determination, acquire high-resolution I(V) curves for multiple diffracted beams. Use a computer-controlled data acquisition system to measure the intensity of selected beams as the electron beam energy is ramped (e.g., in 1-5 eV steps over a wide energy range, typically 50-500 eV).

- Data Extraction and Processing: Extract the raw intensity data. Perform background subtraction and normalize the intensities to account for the incident beam current.

- Theoretical Modeling and Calculation: Propose an initial atomic structure model based on the qualitative symmetry analysis. Use a software package like ViPErLEED to set up the computational parameters. The software will automatically manage the calculation of theoretical I(V) curves for the model, handling parallelization and convergence monitoring [15].

- Structural Optimization: The software performs a structural optimization by refining the atomic coordinates in the model (e.g., layer spacings, buckling amplitudes) and comparing the resulting theoretical I(V) curves to the experimental data. This is an iterative process that minimizes a reliability factor (R-factor). The software's automated search procedures, which can preserve the known symmetries, are used to find the global minimum [15].

- Validation: The final, optimized structure is validated by the quality of the fit between the full set of experimental and theoretical I(V) curves and the achieved R-factor.

Workflow Visualization

The following diagram illustrates the integrated workflow for qualitative and quantitative LEED surface structure analysis.

Low Energy Electron Diffraction (LEED) is a cornerstone technique in surface science for determining the atomic-scale structure of crystalline surfaces. The power of LEED extends beyond qualitative analysis of surface symmetry; through the measurement and analysis of Intensity-Voltage (I-V) curves, it becomes a powerful tool for quantitative surface crystallography. When a beam of low-energy electrons (typically 20-200 eV) is incident on a well-ordered crystal surface, it diffracts to produce a pattern of spots corresponding to the surface periodicity. The intensity of any given diffraction spot is not constant but varies significantly with the energy (voltage) of the incident electrons. This variation is the I-V curve, and it contains a wealth of information about the precise positions of atoms within the surface unit cell [17].

The recording and analysis of LEED I-V curves form the experimental basis for determining surface structures. The underlying principle is that the I-V curve for a specific diffraction spot is sensitive to the vertical arrangement of atoms relative to the surface plane. Electrons with energies in the LEED range have wavelengths comparable to atomic spacings (0.87–2.7 Å for 20–200 eV electrons) and a very short inelastic mean free path, confining their diffraction primarily to the first few atomic layers [17]. This makes LEED I-V exceptionally surface-sensitive. The recorded I-V curves are compared to theoretical curves generated from trial structures. By iteratively refining the structural model until the theoretical I-V curves match the experimental ones, researchers can determine atomic coordinates, layer spacings, and the presence of surface reconstructions with high precision [18] [17].

Experimental Protocol: Recording LEED I-V Curves

The acquisition of high-quality, quantitative I-V curves requires meticulous attention to sample preparation, experimental conditions, and data collection procedures. The following protocol details the essential steps.

Sample Preparation and Surface Cleaning