Oxide Surface Properties Compared: From Fundamental Chemistry to Advanced Biomedical Applications

This article provides a comprehensive comparison of oxide surface properties, tailored for researchers and professionals in drug development and biomedical science.

Oxide Surface Properties Compared: From Fundamental Chemistry to Advanced Biomedical Applications

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive comparison of oxide surface properties, tailored for researchers and professionals in drug development and biomedical science. It explores the foundational chemical principles governing surface interactions, details advanced characterization and engineering methodologies, addresses key challenges in biocompatibility and functionalization, and presents rigorous validation and comparative frameworks. By synthesizing insights across these four intents, this review serves as a strategic guide for selecting and optimizing oxide materials to enhance the performance of drug delivery systems, diagnostic sensors, and antimicrobial coatings.

The Fundamental Building Blocks: Understanding Oxide Surface Chemistry and Interactions

In materials science and nanotechnology, the surface properties of materials dictate their performance and applications. Surface charge, hydrophilicity, and functional groups represent three interconnected fundamental properties that control interactions at the solid-liquid interface. These properties are particularly crucial for oxide materials, which are extensively utilized in fields ranging from environmental remediation to targeted drug delivery. Surface charge governs electrostatic interactions with ions, molecules, and biological systems, while hydrophilicity determines wetting behavior and compatibility with aqueous environments. Surface functional groups provide the chemical moieties that impart specific reactivity and modification potential. This guide provides a comparative analysis of these key physicochemical properties across major oxide material systems, offering researchers a structured framework for material selection and design based on quantitative data and standardized measurement methodologies.

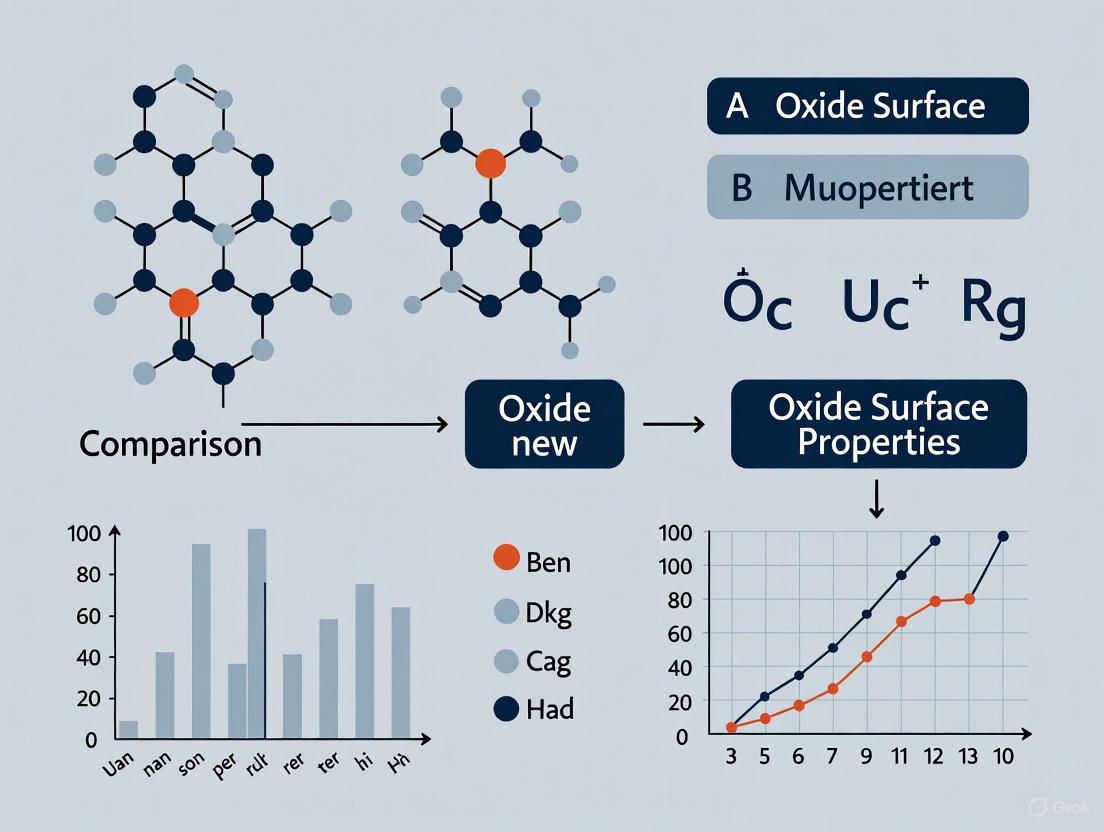

Comparative Analysis of Oxide Surface Properties

The performance of oxide materials in research and applications is directly determined by their surface characteristics. The table below provides a systematic comparison of key surface properties across prominent oxide material systems.

Table 1: Comparative Surface Properties of Selected Oxide Materials

| Material System | Key Functional Groups | Surface Charge Behavior | Hydrophilicity | Primary Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Graphene Oxide (GO) | -COOH, -OH, -C-O-C, epoxide [1] [2] | pH-dependent; IEP typically ~3-4; positive charge at low pH, negative at high pH [1] [3] | Highly hydrophilic due to oxygen-containing groups [2] [4] | Environmental adsorption, drug delivery, nanocomposites [1] [2] |

| Iron Oxide (Fe₃O₄) | Fe-O, OH (surface hydroxyl) [5] [6] | pH-dependent; IEP ~6-7; variable with coating [5] [6] | Moderate; can be enhanced with hydrophilic coatings [5] [7] | Magnetic separation, drug delivery, hyperthermia [5] [7] |

| Copper Oxide (CuO) | Cu-O, surface hydroxyl [8] [7] | pH-dependent; typically positive at physiological pH [8] | Variable; can be modified with polymers [8] | Drug delivery, antimicrobial applications [8] [7] |

| Titanium Oxide (TiO₂) | Ti-O, surface hydroxyl [9] | pH-dependent; IEP ~5-6 [9] | Highly hydrophilic, especially UV-treated [9] | Photocatalysis, coatings, antimicrobial surfaces [9] |

| Polyamide Membranes | -COOH, -NH₂ [3] [10] | Highly pH-dependent; negative above pH ~4-5 [3] [10] | Hydrophilic (contact angle ~50-70°) [3] [10] | Water purification, desalination [3] [10] |

Experimental Characterization Methodologies

Surface Charge Analysis via Zeta Potential

Principle: The zeta potential represents the electrical potential at the slipping plane of a particle in suspension. It is a crucial parameter for predicting colloidal stability and surface interactions [3].

Standard Protocol:

- Sample Preparation: Prepare a stable suspension of the oxide material in a background electrolyte (typically 1-10 mM NaCl or KCl). For pH-dependent measurements, use aliquots adjusted across the relevant pH range (e.g., pH 2-10) using HCl and NaOH [3] [6].

- Instrumentation: Utilize a zeta potential analyzer equipped with a programmable titrator. The SurPASS 3 instrument, for example, determines surface zeta potential via streaming potential or streaming current measurements and allows fully automated analysis over a wide pH range [3].

- Measurement: The instrument measures the voltage (streaming potential) or current (streaming current) generated when electrolyte solution is forced to flow through a membrane or along a flat surface. The zeta potential (ζ) is calculated using the Helmholtz-Smoluchowski equation [3].

- Data Analysis: Plot zeta potential versus pH to identify the isoelectric point (IEP), where ζ = 0 mV. The magnitude and sign of the zeta potential at specific pH values indicate surface charge density and sign [3] [10].

Hydrophilicity Assessment via Contact Angle

Principle: Contact angle measurement quantifies the wettability of a surface by measuring the angle formed at the solid-liquid-vapor interface. Lower contact angles indicate greater hydrophilicity [4] [10].

Standard Protocol:

- Sample Preparation: Prepare a smooth, clean, and dry surface of the material. For membranes, flat sheets are typically used. Ensure consistent surface roughness across comparisons [10].

- Measurement: Using a contact angle goniometer, place a small volume of ultrapure water (typically 2-5 µL) on the surface. Capture an image of the droplet immediately after deposition.

- Analysis: Software analyzes the droplet shape to determine the contact angle. The surface is classified as:

- Environmental Control: For consistent results, control temperature and humidity during measurement. Multiple measurements across the surface provide statistical reliability [10].

Functional Group Identification via FTIR Spectroscopy

Principle: Fourier-Transform Infrared (FTIR) spectroscopy identifies functional groups by measuring their absorption of infrared light at specific wavelengths, corresponding to vibrational transitions [8] [5].

Standard Protocol:

- Sample Preparation: For solid oxides, use KBr pellet method or attenuated total reflectance (ATR) technique. Ensure samples are dry to avoid water interference.

- Measurement: Acquire spectrum in the range of 4000-400 cm⁻¹ with appropriate resolution (typically 4 cm⁻¹). Collect background spectrum under identical conditions.

- Spectral Analysis: Identify characteristic absorption bands:

The following diagram illustrates the relationship between key surface properties and the experimental techniques used to characterize them.

Property Interrelationships and Performance Implications

Surface Charge-Functional Group Relationships

Functional groups directly determine the surface charge characteristics of oxide materials through their pH-dependent ionization behavior. Carboxyl groups (-COOH) deprotonate to -COO⁻ at higher pH, contributing negative charge, while amine groups (-NH₂) protonate to -NH₃⁺ at lower pH, contributing positive charge [1] [10]. In graphene oxide, the abundance of carboxyl and hydroxyl groups creates a strongly negative surface charge above pH 4, which facilitates electrostatic attraction of cationic contaminants like heavy metals [1]. Amine-functionalized graphene oxide demonstrates superior adsorption capacity for Cr(VI) oxyanions in acidic conditions due to protonation of amine groups, generating positive surface sites that electrostatically attract HCrO₄⁻ species [1]. The interplay between different functional groups creates complex charge distribution patterns that govern interfacial behavior.

Hydrophilicity-Surface Chemistry Coupling

Hydrophilicity is primarily determined by the presence of polar functional groups that can form hydrogen bonds with water molecules. Graphene oxide's exceptional hydrophilicity stems from its abundant oxygen-containing functional groups (-OH, -COOH, C-O-C), which create a water-attractive surface [2] [4]. This property is crucial for applications in aqueous environments, including water treatment membranes and biological systems. Membrane surface modifications often aim to increase hydrophilicity by introducing functional groups like hydroxyls or carboxyls, which improve water flux and reduce fouling by creating a hydration barrier that repels hydrophobic contaminants [3] [4]. The modification of polymer membranes with hydrogel layers or specific functional groups changes the surface from hydrophobic to hydrophilic, significantly reducing fouling propensity [3].

Synergistic Effects in Application Performance

The interdependence of these surface properties creates synergistic effects that determine application efficacy. In drug delivery systems, surface charge controls electrostatic drug loading and release kinetics, while hydrophilicity influences biocompatibility and circulation time [8] [7]. Copper oxide nanoparticles demonstrate high loading capacity for Pt(II) drugs like cisplatin (949 mg g⁻¹), attributed to favorable coordination between Pt centers and surface oxygen atoms on CuO, facilitated by specific surface chemistry [8]. Similarly, in environmental applications, graphene oxide functionalized with amine groups achieves enhanced Cr(VI) removal through the combined effects of protonated positive surface charge (electrostatic attraction) and expanded interlayer spacing (enhanced access to binding sites) [1]. These examples highlight how tailored surface properties enable optimization of material performance for specific applications.

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Successful characterization of surface properties requires specific reagents and instrumentation. The table below details essential solutions for comprehensive surface analysis.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for Surface Characterization

| Reagent/Material | Function/Purpose | Application Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Background Electrolytes (NaCl, KCl) | Control ionic strength; enable zeta potential measurements | Zeta potential analysis across pH range [3] [6] |

| pH Adjustment Solutions (HCl, NaOH) | Modify solution pH to study pH-dependent properties | Surface charge titration; IEP determination [3] [6] |

| Standard Buffers | Calibrate pH meters with known accuracy | Ensuring measurement precision in pH-dependent studies [6] |

| Ultrapure Water (HPLC grade) | Minimize interference from impurities in wettability studies | Contact angle measurements; solution preparation [10] |

| KBr Crystal/ Powder | Medium for FTIR sample preparation | FTIR analysis of functional groups [8] [5] |

| Model Compounds/Probes | Characterize specific surface interactions | Fulvic acid, humic acid for NOM adsorption studies [6] |

Surface charge, hydrophilicity, and functional groups represent a triad of interconnected properties that collectively determine the interfacial behavior and application performance of oxide materials. The comparative data presented in this guide demonstrates that while common principles govern these properties across material systems, each oxide family exhibits distinct characteristics that recommend it for specific applications. Graphene oxide stands out for its rich surface chemistry and tunable properties, iron oxides for their magnetic responsiveness, and copper oxides for their coordination chemistry with therapeutic agents. Researchers can leverage these structure-property relationships to design optimized materials for targeted applications through systematic characterization using the standardized methodologies outlined herein. The continuing advancement of surface modification techniques and characterization technologies will further enhance our ability to precisely engineer these critical surface properties for emerging applications in nanotechnology, medicine, and environmental science.

The interaction of organic molecules with solid surfaces is a fundamental process underpinning advancements in catalysis, sensor technology, and drug development. For decades, strategic molecular design often leveraged aromatic π-systems for their ability to form strong interactions with metallic surfaces. However, emerging research reveals a dramatic shift in this paradigm when the substrate is a metal oxide. A seminal 2025 study combined spectroscopic and computational approaches to demonstrate that on metal oxide surfaces, lone pair interactions significantly dominate over aromatic binding, and the presence of aromatic groups can even reduce overall adhesion strength [11] [12] [13]. This guide provides a detailed, evidence-based comparison of these two interaction forces, offering researchers a framework for designing molecules with tailored surface affinity for metal oxides.

Comparative Analysis: Lone Pair vs. Aromatic Binding

The following table synthesizes key experimental and computational findings on the characteristics of lone pair and aromatic interactions with metal oxide surfaces.

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of Lone Pair and Aromatic Interactions on Metal Oxide Surfaces

| Feature | Lone Pair Interactions | Aromatic (π-System) Interactions |

|---|---|---|

| General Binding Strength | Dominant and significantly stronger [11] | Weaker; can reduce overall binding when both are present [11] |

| Primary Interaction Site | Metal cation (e.g., Zn²⁺) on the oxide surface [11] [14] | Less favorable sites; potentially anionic oxygen sites [14] |

| Key Determinant | The lone pair itself, not the parent atom or functional group [11] | π-conjugated electron system [11] |

| Effect on Sensor Conductivity | Strong interaction alters electron distribution, key for sensor effect [15] | Weaker interaction leads to a smaller change in electron distribution [11] [15] |

| Theoretical Validation (DFT) | Confirmed by Frontier Molecular Orbital (FMO), Non-Covalent Interaction (NCI), and Density of States (DOS) analyses [11] [12] | Computational models show weaker affinity and secondary role [11] |

| Contrast with Pure Metal Surfaces | Behaves differently; on pure metals, lone pairs and aromatics can act synergistically [11] | Behaves differently; synergy with lone pairs is lost on metal oxides [11] |

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Core Experimental Workflow

The definitive conclusions in the 2025 study were drawn from a combined experimental and computational workflow, visualized below. This integrated approach ensures that theoretical predictions are validated with empirical data, providing a robust model for understanding surface interactions [11].

Detailed Methodological Breakdown

Material Synthesis and Surface Preparation

- Zinc Oxide Nanoparticles: Used as the representative metal oxide substrate. Their high surface-to-volume ratio maximizes interaction sites for sensitive measurements [11].

- Isoxazole Derivatives: A series of four organic molecules containing both lone pair-bearing atoms (like nitrogen or oxygen) and aromatic functionalities were synthesized. This allows for direct comparison of the two interaction types within a single molecule [11] [12].

Spectroscopic and Scattering Techniques

- Fluorescence Spectroscopy: Employed to monitor changes in the electronic environment of the molecules upon adsorption. Shifts in fluorescence emission spectra provide indirect evidence of binding strength and the nature of the surface-molecule interaction [11].

- Dynamic Light Scattering (DLS): Used to measure the hydrodynamic size and stability of nanoparticle dispersions before and after molecular adsorption. A rare correlation between DLS and fluorescence data consistently confirmed the stronger interaction of lone pairs [11] [12].

Computational Validation with Density Functional Theory (DFT)

Quantum chemical calculations were critical for confirming the experimental observations at an electronic level [11] [12].

- Frontier Molecular Orbital (FMO) Analysis: Reveals the energy and shape of the highest occupied and lowest unoccupied molecular orbitals, indicating which parts of the molecule are most likely to interact with the surface.

- Non-Covalent Interaction (NCI) Analysis: Visualizes the regions and strengths of weak interactions, such as van der Waals forces or hydrogen bonds, between the molecule and the surface.

- Density of States (DOS) Analysis: Shows how the electronic energy levels of the molecule and the surface change upon interaction, providing insight into charge transfer and bonding.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 2: Key Reagents, Materials, and Computational Tools for Oxide Surface Interaction Studies

| Category/Item | Specific Examples & Specifications | Primary Function in Research |

|---|---|---|

| Metal Oxide Substrates | Zinc Oxide (ZnO) nanoparticles [11]; TiO₂ (anatase, rutile), MgO [14] | Provides the reactive surface for molecular adsorption. ZnO is a key model system. |

| Probe Molecules | Custom-synthesized isoxazole derivatives with lone pair and aromatic groups [11] | Serves as the adsorbate to compare and contrast different binding modalities. |

| Spectroscopic instruments | Fluorescence Spectrometer [11]; Electron Paramagnetic Resonance (EPR) with ¹⁷O isotopic enrichment [16] | Probes electronic changes upon binding and characterizes the metal-support chemical bond. |

| Scattering & Size Analyzers | Dynamic Light Scattering (DLS) instrument [11] | Measures nanoparticle size distribution and aggregates formation, indicating interaction strength. |

| Computational Software | Density Functional Theory (DFT) packages [11] [17] | Models the interaction at an atomic level, calculating energies, orbital interactions, and electronic structure. |

| Analysis Tools | Adaptive Natural Density Partitioning (AdNDP), Natural Bond Orbital (NBO) analysis [17] | Analyzes and visualizes chemical bonding, including delocalized bonds and aromaticity in complex clusters. |

The body of evidence unequivocally demonstrates that lone pair interactions are the dominant force in binding to metal oxide surfaces, fundamentally overturning the conventional wisdom derived from pure metal surface chemistry. For researchers and developers working in catalysis, sensor design, or pharmaceutical sciences, this necessitates a strategic pivot. Optimizing functional groups for steric or traditional electronic effects is less impactful than ensuring the presence and accessibility of electron lone pairs for direct interaction with surface metal cations [11]. This new understanding provides a powerful, rational framework for designing the next generation of functional molecules tailored specifically for applications involving metal oxides.

Structural Stability and Oxidation Kinetics of Nanomaterial Surfaces

The structural stability and oxidation kinetics of nanomaterial surfaces are fundamental properties governing their performance in applications ranging from heterogeneous catalysis to energy storage and biomedical technologies. Unlike bulk materials, nanomaterials exhibit distinct oxidation behaviors due to their high surface-to-volume ratios, quantum confinement effects, and increased susceptibility to environmental influences. Understanding these differences is crucial for designing nanomaterials with enhanced durability and tailored functional properties. This guide provides a comparative analysis of oxidation behaviors across different nanomaterial systems, supported by experimental data and detailed methodologies, to inform research and development across scientific disciplines.

Comparative Analysis of Nanomaterial Oxidation

The oxidation of nanomaterials is a complex process influenced by material composition, structure, size, and environmental conditions. The following sections compare key nanomaterial systems, highlighting their distinct oxidation pathways and stability profiles.

Metallic Nanoparticles

Supported Palladium (Pd) Nanoparticles: The oxidation dynamics of supported metal nanoparticles are profoundly influenced by their interface with the support material. In situ environmental scanning transmission electron microscopy (ESTEM) studies on Pd nanoparticles supported on ceria (CeO₂) reveal two distinct oxidation pathways determined by the crystallographic orientation of the support [18].

- On CeO₂(100) surfaces, Pd nanoparticles undergo self-adaptive oxidation, where oxidation preferentially nucleates at the metal-support interface. This interfacial oxide layer grows faster than surface oxides and can propagate through the entire particle, leading to complete oxidation [18].

- On CeO₂(111) surfaces, Pd nanoparticles exhibit surface oxidation, where the oxide layer forms on the external surface and progresses inward. This pathway is generally slower than interfacial oxidation [18].

The driving force for this difference is the epitaxial match between the metal oxide and the support. A strong interfacial epitaxy promotes self-adaptive oxidation, a finding that provides a strategic principle for regulating oxidation dynamics through interface engineering [18].

Table 1: Comparative Oxidation Dynamics of Supported Pd Nanoparticles

| Support Facet | Oxidation Dynamics | Nucleation Site | Oxidation Rate | Governing Factor |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CeO₂(100) | Self-adaptive oxidation | Metal-support interface | Fast | Strong interfacial epitaxy |

| CeO₂(111) | Surface oxidation | External nanoparticle surface | Slower | Weak interfacial epitaxy |

Metal Oxide Nanomaterials

Cobalt-Chromium (Co-Cr) Spinel Oxides: The structural stability of complex metal oxides under operational conditions is critical for electrocatalysis. A multimodal study on ~20 nm Co-Cr spinel nanoparticles (CoCr₂O₄ and Co₂CrO₄) during the oxygen evolution reaction (OER) revealed distinct surface reconstruction behaviors [19].

- CoCr₂O₄ undergoes an activation process involving substantial Cr dissolution. This creates vacancies that facilitate hydroxide ion intercalation, leading to a highly reversible structural transformation between (

Co^II_Td, Cr)(OH)₂ and (Co^III_Oct, Cr)OOH. This process enhances both OER activity and long-term stability [19]. - Co₂CrO₄ forms a thin (1-2 nm), amorphous Cr-based (oxy)hydroxide layer on its surface. However, this layer is gradually depleted due to continuous Cr dissolution, leading to a deterioration of OER activity over time [19].

This contrast demonstrates how composition-dependent cation dissolution and subsequent transformation pathways directly dictate the functional stability of oxide nanomaterials.

Iron Nanowires: The oxidation of one-dimensional nanostructures presents unique challenges and opportunities. Reactive molecular dynamics (MD) simulations of iron nanowires have quantified how size, temperature, and defects affect their oxidation kinetics and mechanical properties [20].

- Size Effect: Slender nanowires exhibit faster oxidation and develop thicker oxide shells due to their higher surface-to-volume ratio.

- Temperature Effect: Elevated temperatures significantly accelerate oxidation kinetics. For instance, a temperature increase from 300 K to 600 K can triple the oxide layer thickness on a 5 nm diameter nanowire over the same duration [20].

- Mechanical Property Degradation: The resulting amorphous oxide shell significantly degrades mechanical properties. A 5 nm nanowire can experience a ~50% reduction in elastic modulus and a ~70% reduction in yield strength after oxidation [20].

Table 2: Effects of Diameter and Temperature on Oxidation Kinetics and Mechanical Properties of Iron Nanowires [20]

| Nanowire Diameter | Temperature | Oxide Layer Thickness | Reduction in Elastic Modulus | Reduction in Yield Strength |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 5 nm | 300 K | ~8 Å | ~25% | ~45% |

| 5 nm | 600 K | ~24 Å | ~50% | ~70% |

| 10 nm | 300 K | ~5 Å | ~15% | ~30% |

| 10 nm | 600 K | ~15 Å | ~35% | ~55% |

Organic and Polymeric Nanoparticles

Polydopamine Nanoparticles (PDA NPs): The stability and functional properties of organic nanoparticles are governed by their molecular cross-linking and surface chemistry. A study on PDA NPs synthesized under controlled oxidation conditions showed that their size, surface properties, and photothermal performance evolve significantly over time [21].

- Growth and Stability: The optimal synthesis window for uniform, colloidally stable PDA NPs was found to be 24 hours, yielding particles with a hydrodynamic diameter of ~154 nm and a zeta potential of ~ -41 mV [21].

- Structural Evolution: Prolonged oxidation (up to 120 hours) leads to progressive transformation of catechol groups into quinones, increased π-π stacking, and greater surface roughness [21].

- Functional Impact: This molecular evolution directly modulates photothermal conversion efficiency. NPs oxidized for 120 hours reached a temperature change (ΔT) of 48.9 °C under laser irradiation, outperforming both earlier-stage PDA NPs and natural Sepia melanin [21].

Experimental Protocols for Assessing Oxidation and Stability

To generate comparable data on nanomaterial oxidation, standardized experimental protocols are essential. Below are detailed methodologies for key techniques cited in this field.

In Situ Electron Microscopy for Oxidation Dynamics

Protocol: Atomic-Scale Tracking of Oxidation in Supported Nanoparticles [18]

- Sample Preparation: Synthesize well-defined model catalysts (e.g., via solid grinding or wet impregnation) with metal nanoparticles (e.g., Pd) uniformly dispersed on a support (e.g., CeO₂ nanocubes).

- Pretreatment: Reduce the as-prepared sample in a flow of H₂ (e.g., 50 mL/min) at 300°C for 3 hours in a tube furnace to remove pre-existing oxides.

- In Situ E(S)TEM Setup: Load the pre-treated powder onto a specialized E(S)TEM holder. Introduce oxygen gas to an environmental pressure of 5 Pa within the microscope column.

- Thermal Activation: Increase the sample temperature to 350°C using the holder's heating capability to initiate oxidation.

- Image Acquisition: Acquire high-angle annular dark-field (HAADF-STEM) images at regular intervals (e.g., every few minutes) with the electron beam blanked between exposures to minimize beam effects.

- Data Analysis: Analyze temporal image sequences to identify nucleation sites (interface vs. surface), track oxide front propagation, and measure lattice spacing changes to identify oxide phases.

Quantification of Reactive Surface Sites

Protocol: Methanol Chemisorption and Temperature-Programmed Surface Reaction (TPSR) [22] This in chemico method quantifies the density and nature of reactive sites on metal oxide nanomaterials.

- Reactor Loading: Mix 100-250 mg of the nanomaterial powder with 0.5 g of an inert diluent like silicon carbide (SiC) and pack it into a fixed-bed microreactor.

- Methanol Chemisorption: Expose the catalyst to a stream of methanol vapor in an inert carrier gas at a controlled temperature (typically 100°C, or 50°C for highly reactive materials like ZnO). This results in the formation of surface methoxy (-OCH₃) groups.

- Temperature-Programmed Surface Reaction (TPSR): After purging to remove physisorbed methanol, heat the reactor linearly (e.g., 10°C/min) under an inert gas flow.

- Product Detection: Monitor the reactor effluent with a mass spectrometer (MS) to detect the release of reaction products:

- Dimethyl ether (CH₃OCH₃) indicates acidic sites.

- Formaldehyde (HCHO) indicates redox sites.

- Carbon dioxide (CO₂) can indicate basic sites (above 300°C) or highly reactive redox sites (below 300°C).

- Data Quantification: Integrate the product desorption peaks. The number of reactive sites is proportional to the amount of methanol consumed or specific products formed.

Photothermal Performance Evaluation

Protocol: Assessing Photothermal Conversion Efficiency [21]

- Sample Preparation: Disperse the nanoparticles (e.g., PDA NPs or melanin) in a solvent (e.g., water) at a standardized concentration.

- Irradiation Setup: Place a quartz cuvette containing the nanoparticle dispersion in the path of a continuous-wave laser beam (e.g., 532 nm wavelength). Use a pinhole to define the beam spot size (e.g., 3 mm diameter).

- Temperature Monitoring: Position an infrared thermal camera (e.g., FLIR E40) to record the temperature change at the laser spot on the cuvette in real-time.

- Data Collection: Irradiate the sample for a fixed duration (e.g., several minutes) and record the temperature profile over time.

- Analysis: Calculate the maximum temperature change (ΔT) achieved. The photothermal conversion efficiency can be calculated by comparing the heat output of the sample to the incident laser power, considering heat dissipation losses.

Visualization of Experimental Workflows

The following diagram illustrates the logical sequence and decision points in a generalized methodology for investigating nanomaterial surface oxidation.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents and Materials

Successful experimentation in this field relies on a suite of specialized materials and reagents. The following table details essential items and their functions.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for Nanomaterial Oxidation Studies

| Item Name | Function/Application | Specific Example Use |

|---|---|---|

| Ceria (CeO₂) Nanocube Supports | Well-defined model support with specific crystallographic facets ({100}) to study metal-support interaction effects on oxidation. | Used as a support for Pd nanoparticles to investigate facet-dependent oxidation dynamics [18]. |

| Dopamine Hydrochloride | Monomer for the synthesis of polydopamine nanoparticles (PDA NPs) via oxidative self-polymerization. | Polymerized in alkaline solution (ammonium hydroxide/ethanol/water) to create tunable PDA NPs for photothermal studies [21]. |

| Methanol (CH₃OH) | Probe molecule for chemisorption and TPSR experiments to quantify and characterize reactive surface sites on metal oxides. | Chemisorbed onto nanomaterial surfaces to form methoxy species; subsequent TPSR reveals site acidity/redox activity [22]. |

| Antioxidants (DTT, Cys, GSH) | Used in acellular assays to measure the oxidative potential of ENMs by tracking the consumption of thiol groups. | Dithiothreitol (DTT), Cysteine (Cys), and Glutathione (GSH) solutions incubated with ENMs to measure oxidation rates [22]. |

| ROS Probes (RNO, DCFH₂-DA) | Chemical probes for detecting and quantifying the generation of reactive oxygen species (ROS) by ENMs in cell-free systems. | N,N-dimethyl-4-nitrosoaniline (RNO) for hydroxyl radicals; 2',7'-dichlorodihydrofluorescein diacetate (DCFH₂-DA) for general ROS [22]. |

| Ammonium Hydroxide (NH₄OH) | Catalyst and pH controller for the alkaline synthesis of polymeric nanoparticles like PDA. | Used to adjust the pH of the reaction mixture to initiate and control the polymerization of dopamine into nanoparticles [21]. |

| High-Purity Metal Salts & Precursors | Source materials for the synthesis of metal and metal oxide nanomaterials (e.g., via coprecipitation, hydrothermal methods). | Salts like cobalt and chromium nitrates/chlorides used to synthesize Co-Cr spinel oxide nanoparticles [19]. |

The field of advanced materials has undergone a significant transformation, evolving from the study of simple metal oxides to the sophisticated exploration of graphene-based nanomaterials. This progression represents not merely a change in chemical composition but a fundamental shift in how scientists approach material design for targeted applications. Simple metal oxides, such as titanium dioxide (TiO₂), zinc oxide (ZnO), and cobalt oxide (Co₃O₄), have long been valued for their catalytic, electronic, and structural properties [23]. These materials establish the foundation of oxide research, offering well-characterized behaviors and predictable performance across various applications from catalysis to energy storage.

The emergence of graphene oxide (GO) and its derivatives has introduced a new dimension to materials science, characterized by tunable surface chemistry and exceptional physical properties [24]. Unlike traditional metal oxides with fixed crystalline structures, graphene oxide presents a two-dimensional platform that can be chemically functionalized to achieve specific characteristics, creating what researchers term "compositional complexity" [25]. This complexity arises from the ability to precisely control oxygen-containing functional groups (epoxy, hydroxyl, carboxyl) on the graphene backbone, enabling unprecedented customization for specialized applications from drug delivery to energy storage [24].

This guide objectively compares the performance characteristics of simple metal oxides and graphene oxide composites across multiple domains, supported by experimental data and standardized testing methodologies. By examining these material classes through the lens of oxide surface properties research, we provide a framework for material selection based on application-specific requirements rather than theoretical potential alone.

Fundamental Properties Comparison

The fundamental differences between simple metal oxides and graphene oxide derivatives originate from their distinct atomic structures and resulting physicochemical properties. Understanding these core characteristics is essential for predicting material behavior in practical applications.

Simple metal oxides typically exhibit well-defined crystalline structures with specific coordination geometries around metal centers. For example, TiO₂ exists primarily in anatase and rutile phases with bandgaps of approximately 3.2 eV, making it effective for UV-driven photocatalysis but limited in visible light absorption [23]. Similarly, ZnO possesses a wide bandgap (3.37 eV) with significant exciton binding energy, while magnetic oxides like Co₃O₄ feature mixed valence states (Co²⁺/Co³⁺) that enable rich redox chemistry [23]. These intrinsic properties make metal oxides particularly suitable for applications leveraging their semiconductor behavior, catalytic activity, and thermal stability.

Graphene oxide fundamentally differs through its two-dimensional honeycomb carbon lattice decorated with oxygen functional groups [24]. This structure creates a unique set of properties including high surface area (theoretically ~2600 m²/g), mechanical strength, and tunable surface chemistry [25]. The presence of hydroxyl, epoxy, and carboxyl groups makes GO hydrophilic and readily dispersible in aqueous media, facilitating solution-based processing [24]. When GO undergoes reduction to form reduced graphene oxide (rGO), the partial restoration of the sp² carbon network yields materials with enhanced electrical conductivity (>10² S/m) while retaining some oxygen functionality for further chemical modification [25].

Table 1: Comparison of Fundamental Properties Between Metal Oxides and Graphene Oxide

| Property | Simple Metal Oxides | Graphene Oxide (GO) | Reduced Graphene Oxide (rGO) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Structural Dimensionality | 3D crystalline structures | 2D layered structure | 2D layered with defects |

| Electrical Conductivity | Insulators to semiconductors | Insulating (~10⁻³ S/m) | Conductive (>10² S/m) |

| Surface Area (m²/g) | Moderate (10-100) | High (theoretical ~2600) | High (500-1500) |

| Surface Chemistry | Metal-O bonds, oxygen vacancies | Oxygen functional groups | Residual oxygen groups |

| Processability | Limited dispersion | Excellent water dispersibility | Moderate dispersion |

| Mechanical Flexibility | Brittle | Flexible but weak | Flexible and strong |

The surface adhesion properties of these materials further highlight their differences. Systematic studies using inverse gas chromatography (IGC) reveal a consistent hierarchy in adhesion energies: graphene (G) > reduced graphene oxide (rGO) > graphene oxide (GO) [26]. This progression reflects the changing balance between dispersive (van der Waals) and polar (hydrogen bonding) interactions as oxygen content varies. Temperature significantly influences these adhesion properties, with elevated temperatures modifying surface energy components and interfacial interactions in predictable ways [26].

Performance Metrics Across Applications

Energy Storage Capabilities

In energy storage applications, particularly supercapacitors and batteries, both metal oxides and graphene-based materials demonstrate distinct advantages and limitations. Transition metal oxides such as RuO₂, MnO₂, and Co₃O₄ exhibit pseudocapacitive behavior through reversible redox reactions, enabling high specific capacitance values. For instance, Fe-doped Co₃O₄ demonstrates a specific capacitance of 588.5 F g⁻¹, leveraging the Co²⁺/Co³⁺ and Fe³⁺ redox couples for charge storage [23]. Similarly, Ni-doped V₂O₅ nanosheets achieve remarkable specific capacity (3485 F g⁻¹ at 1 A g⁻¹) through enriched redox sites and optimized oxygen deficiency [23].

Graphene oxide and its derivatives contribute to energy storage through both electrical double-layer capacitance (EDLC) and pseudocapacitance when functionalized with appropriate species. Pristine GO's limited conductivity restricts its direct application, but functionalized GO composites address this limitation. For example, tris(hydroxymethyl)aminomethane-functionalized graphene oxide (GO@T) demonstrates a specific capacitance of 549.8 F g⁻¹ at 2.5 A g⁻¹ with excellent cyclic stability (80% capacitance retention after 5500 cycles) [27]. This performance stems from the prevention of GO sheet restacking, which increases accessible surface area while incorporating nitrogen-containing functional groups that may contribute to pseudocapacitance.

Table 2: Energy Storage Performance Comparison

| Material | Specific Capacitance/Capacity | Cyclic Stability | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|---|

| Fe-doped Co₃O₄ | 588.5 F g⁻¹ | Not specified | Multiple redox couples, bandgap ~2.0 eV |

| Ni-doped V₂O₅ | 3485 F g⁻¹ at 1 A g⁻¹ | Not specified | Oxygen deficiency, enriched redox sites |

| GO@T | 549.8 F g⁻¹ at 2.5 A g⁻¹ | 80% after 5500 cycles | Functionalized GO, prevented restacking |

| N-butyllithium-treated Ti₃C₂Tx MXene | 523 F g⁻¹ at 2 mV s⁻¹ | 96% after 10000 cycles | Surface functionalization |

| WO₃·0.5H₂O/rGO | 241-306 F g⁻¹ | 90% after 10000 cycles | Composite structure |

Environmental Remediation Performance

Environmental applications, particularly photocatalytic degradation and adsorption of pollutants, represent another domain where these material classes show distinctive performance profiles. Metal oxide nanoparticles are extensively employed for photocatalytic degradation of organic pollutants including dyes and pesticides. TiO₂ and ZnO dominate UV-driven photocatalysis, leveraging high oxidative potentials to generate hydroxyl radicals that degrade compounds like methylene blue and rhodamine B [23]. Their effectiveness, however, is constrained by rapid charge recombination and limited visible light absorption due to wide bandgaps.

Graphene oxide membranes demonstrate remarkable filtration capabilities for water treatment, removing over 99% of contaminants including heavy metals and organic pollutants [28]. Their unique layered structure enables precise molecular separation while maintaining high water flux rates, with pilot desalination projects showing 50-60% energy savings compared to reverse osmosis systems [28]. For pesticide removal, GO's oxygen functional groups provide binding sites for various organic contaminants through multiple interaction mechanisms including electrostatic attraction, hydrogen bonding, and π-π interactions [29].

Composite materials that combine metal oxides with graphene derivatives have emerged as particularly effective solutions. For example, TMO/GO nanocomposites integrate the redox properties of transition metal oxides with the electrical conductivity and high surface area of graphene derivatives [23]. These composites demonstrate synergistic effects, such as in Co₃O₄-coated TiO₂ core-shell structures that establish p-n junctions to improve charge separation, achieving nearly 100% degradation of methylene blue within 1.5 hours under UV light compared to 80% for unmodified TiO₂ [23].

Biomedical Application Capabilities

The biomedical domain highlights perhaps the most striking contrast between material classes. Metal oxide nanoparticles find primary application as antibacterial agents, with zinc oxide and copper oxide nanoparticles demonstrating the ability to deactivate 99.9% of bacteria within 10 minutes by releasing reactive oxygen species [30]. These materials are increasingly incorporated into antimicrobial coatings, personal care products, and medical devices.

Graphene oxide exhibits more diverse biomedical capabilities, particularly in drug delivery, biosensing, and tissue engineering. GO's large surface area and biocompatibility enable high drug-loading capacity (approximately 90% for compounds like doxorubicin) with controlled release mechanisms [25]. Functionalization with polyethylene glycol (PEG) further enhances blood circulation time, making GO particularly valuable for targeted cancer therapies where studies have demonstrated up to 60% reduction in systemic side effects [28]. Additionally, GO-based biosensors have shown 95% accuracy in pathogen detection (including SARS-CoV-2) within minutes, highlighting their diagnostic potential [28].

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Synthesis and Functionalization Approaches

The preparation of these materials follows distinct pathways reflective of their chemical nature. Simple metal oxides are typically synthesized through sol-gel processes, hydrothermal methods, or precipitation reactions. For example, TiO₂ nanoparticles can be prepared via sol-gel hydrolysis of titanium alkoxides followed by calcination, controlling crystal phase and particle size through temperature and pH conditions [23]. ZnO nanostructures are often produced through hydrothermal methods at temperatures of 120-200°C, with morphology controlled via capping agents or dopants [23].

Graphene oxide synthesis predominantly follows oxidation protocols such as Hummers' method or its modified variants, which involve treatment of graphite with strong oxidizers like KMnO₄ in concentrated H₂SO₄ [25]. These methods yield GO with adjustable carbon-to-oxygen ratios, enabling tailored properties for specific applications. Functionalization of GO typically exploits the reactivity of oxygen groups; for instance, the amide reaction between GO's carboxyl groups and amines like tris(hydroxymethyl)aminomethane uses coupling agents such as dicyclohexylcarbodiimide (DCC) and catalyst 4-dimethylaminopyridine (DMAP) [27].

Table 3: Standard Synthesis Methods for Metal Oxides and Graphene Oxide

| Material Category | Synthesis Method | Key Reagents/Conditions | Output Characteristics |

|---|---|---|---|

| Metal Oxides | Sol-gel | Metal alkoxides, controlled hydrolysis & calcination | Controlled crystallinity, particle size |

| Metal Oxides | Hydrothermal/solvothermal | Aqueous/organic solution, 120-200°C | Morphological control, nanocrystals |

| Metal Oxides | Chemical precipitation | Metal salts, base precipitation | High yield, aggregation issues |

| Graphene Oxide | Modified Hummers' method | Graphite, KMnO₄, H₂SO₄, NaNO₃ | Adjustable C/O ratio, scalable |

| GO Functionalization | Amide coupling | DCC, DMAP, nucleophilic amines | Covalent attachment, retained dispersibility |

Characterization Techniques

Comprehensive characterization is essential for understanding the structure-property relationships in these materials. Structural analysis of metal oxides typically employs X-ray diffraction (XRD) to determine crystal phase and crystallite size, while electron microscopy (SEM/TEM) reveals morphology and particle size distribution [23]. For graphene-based materials, XRD identifies layer spacing and functionalization success, with GO typically showing a peak at 2θ ≈ 11° corresponding to approximately 0.8 nm interlayer distance [27].

Surface characterization techniques differ significantly between material classes. For metal oxides, surface area analysis via BET nitrogen adsorption and acidity measurements through ammonia-TPD are standard [23]. Graphene materials require different approaches; Fourier-transform infrared (FT-IR) spectroscopy identifies functional groups (C=O at ~1717 cm⁻¹, C-O at ~1024 cm⁻¹), while X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) quantifies elemental composition and carbon-to-oxygen ratios [27]. Thermal gravimetric analysis (TGA) further elucidates the thermal stability and functional group content through controlled heating.

Surface adhesion properties are quantitatively assessed using inverse gas chromatography (IGC), which measures the dispersive and polar components of surface energy through probe molecule interactions [26]. This technique has revealed that adhesion energies follow the hierarchy G > rGO > GO, with temperature significantly influencing these interactions. For example, studies show consistent decrease in London dispersive surface energy (γsᵈ) with increasing temperature across all graphene materials, from approximately 140-170 mJ/m² at 313K to 100-130 mJ/m² at 373K [26].

Electrochemical Testing Protocols

Standardized electrochemical testing is crucial for evaluating energy storage materials. Electrode preparation typically involves creating a slurry of active material (75-85%), conductive carbon (10-15%), and polymer binder (5-10%) in a solvent like N-methyl-2-pyrrolidone, which is then coated onto current collectors such as nickel foam or stainless steel [27].

Performance evaluation employs several complementary techniques. Cyclic voltammetry (CV) measures capacitive behavior through potential cycling at different scan rates (e.g., 5-100 mV/s), with quasi-rectangular curves indicating ideal electrical double-layer capacitance [27]. Galvanostatic charge-discharge (GCD) tests at various current densities (e.g., 2.5-7 A/g) provide specific capacitance values through the equation: Cm = (I × Δt) / (m × ΔV), where I is current, Δt discharge time, m active mass, and ΔV potential window [27]. Long-term stability is assessed through cycling tests, typically 5000-10000 cycles, with capacitance retention reported as a key metric.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for Oxide Research

| Reagent/Material | Function/Application | Examples/Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Transition Metal Salts | Precursors for metal oxide synthesis | Nitrates, chlorides, acetylacetonates |

| Graphite Powder | Starting material for GO synthesis | Flake size affects oxidation efficiency |

| Strong Oxidizers | GO synthesis | KMnO₄, H₂SO₄, NaNO₃ in Hummers' method |

| Coupling Agents | GO functionalization | DCC, EDC for amide bond formation |

| Conductive Additives | Electrode preparation | Carbon black, acetylene black |

| Polymer Binders | Electrode preparation | PVDF, PTFE for slurry stability |

| Current Collectors | Electrode preparation | Nickel foam, carbon paper, foil |

| Electrolytes | Electrochemical testing | Aqueous (KOH, H₂SO₄), organic, ionic liquids |

Computational and Theoretical Frameworks

Computational approaches provide invaluable insights into the fundamental behavior of these materials at the atomic level. Density functional theory (DFT) calculations have revealed that the interaction between transition metal ions and graphene oxide occurs preferentially at specific functional groups [31]. Studies show that hydroxyl (OH) groups generally represent the most favorable adsorption sites for first-row transition metal ions (Cr²⁺, Ni²⁺, Cu²⁺, Zn²⁺), often leading to cleavage of the C-OH bond and formation of TM-OH residues above the graphene basal plane [31]. In contrast, carboxyl (COOH) groups demonstrate the lowest affinity for these metal ions, contradicting some experimental observations that may involve deprotonated carboxyl groups.

Quantum capacitance calculations further elucidate the electrochemical performance of graphene derivatives. DFT studies comparing pristine GO and functionalized GO reveal that tris(hydroxymethyl)aminomethane functionalization significantly enhances quantum capacitance, particularly at negative voltages, explaining the improved supercapacitor performance observed experimentally [27]. These computational insights guide rational material design by predicting how specific functionalizations will alter electronic structure and performance.

The following diagram illustrates the computational workflow for studying metal ion adsorption on graphene oxide surfaces:

Computational Workflow for Studying Metal Ion Adsorption on Graphene Oxide

Research Workflow Visualization

The experimental research process for comparing metal oxide and graphene oxide materials follows a systematic pathway from material synthesis through performance evaluation, as illustrated below:

Comprehensive Research Workflow for Oxide Materials Comparison

The comparative analysis of simple metal oxides and graphene oxide derivatives reveals a complex landscape where material selection must be guided by application-specific requirements rather than presumed superiority of either class.

Simple metal oxides maintain distinct advantages in scenarios requiring well-defined crystalline structures, predictable semiconductor behavior, and straightforward synthesis pathways. Their established history in applications like photocatalysis, where TiO₂ and ZnO demonstrate reliable performance under UV illumination, makes them suitable for large-scale industrial processes where cost and reproducibility are primary concerns [23]. Similarly, the rich redox chemistry of transition metal oxides like Co₃O₄ and MnO₂ continues to make them indispensable for pseudocapacitive energy storage applications [23].

Graphene oxide and its derivatives excel in applications demanding tunable surface chemistry, mechanical flexibility, and composite functionality. The ability to precisely control oxygen functional groups and subsequent chemical modifications makes GO particularly valuable for biomedical applications where specific interactions with biological systems are required [24] [28]. Similarly, GO's two-dimensional structure and solution processability facilitate the creation of advanced membranes for water purification and molecular separation [28].

The most promising developments emerge at the interface of these material classes, where TMO/GO nanocomposites leverage the complementary properties of both components [23]. These hybrid materials demonstrate synergistic effects that overcome individual limitations, such as using conductive graphene derivatives to mitigate the poor electrical conductivity of metal oxides, or employing metal oxide nanoparticles to prevent restacking of graphene sheets. This integrative approach represents the future of oxide materials research, moving beyond simple comparisons to strategic combinations that address complex technological challenges across energy, environment, and healthcare domains.

Synthesis, Characterization, and Engineering Oxide Surfaces for Biomedicine

The performance of functional oxides in applications ranging from catalysis and energy storage to biomedicine is intrinsically governed by their surface characteristics, which are in turn dictated by the synthesis method employed [32]. Advanced synthesis routes—encompassing traditional chemical, emerging green, and bio-based methods—enable precise control over critical surface properties such as specific surface area, defect density, and distribution of reactive sites [33] [22]. This guide provides a comparative analysis of these methodologies, evaluating their effectiveness in engineering oxide surfaces with tailored functionality. By presenting experimental data and protocols, we aim to equip researchers with the information necessary to select optimal synthesis pathways for specific research and development goals, framed within the broader context of oxide surface properties research.

Synthesis Methodologies and Comparative Performance

Advanced synthesis routes for metal oxides can be categorized into chemical, green, and bio-based approaches, each offering distinct advantages and trade-offs in terms of the resulting surface properties, scalability, and environmental impact.

Table 1: Comparison of Advanced Synthesis Routes for Metal Oxides

| Synthesis Method | Key Characteristics | Typical Oxides Synthesized | Resulting Surface Properties | Experimental Performance Data |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chemical (Nanobubble-Assisted) [33] | Uses gas nanobubbles as templates and exfoliation agents; modified Marcano's method (H2SO4/H3PO4/KMnO4). | Graphene Oxide (GO) | ↑ Specific Surface Area (109.4 m²/g), ↑ microporosity, ↑ oxygenated functional groups (C–O), enhanced crystallinity. | Specific surface area increased 2.5-fold; Boosts ion diffusion kinetics. |

| Chemical (Colloidal Atomic Layer Deposition) [34] | Precisely controlled core-shell nanostructure growth; enables creation of defined metal-oxide interfaces. | Cu-ZrOx, Cu-TiOx, Cu-MgOx | Tailored interfacial sites for specific catalytic reactions; high stability under operational conditions. | Enhanced selectivity for multicarbon products in CO₂ reduction reaction (CO₂RR). |

| Green (Solvent-Free/Alternative Reagents) [35] | Utilizes dipyridyldithiocarbonate (DPDTC) as a recyclable by-product reagent; minimizes organic solvent waste. | Not specified (method for fundamental bonds) | Surface functionality for esters and thioesters; applicable to pharmaceutical building blocks. | Efficient bond formation with recyclable by-products; applied to synthesis of Nirmatrelvir (Paxlovid). |

| Green/Niobium-Based Catalysis) [35] | Employs niobium oxide nanoparticles embedded in mesoporous silica; stable, water-tolerant Brønsted and Lewis acidity. | Niobium Oxide (Nb₂O₅) | High surface area, stable acid sites for condensation and esterification reactions. | High selectivity to 4-(furan-2-yl)but-3-en-2-one (C8); stable over recycling runs. |

| Vapor-Phase Growth & Hydrothermal [32] | High-temperature, high-pressure crystallization from aqueous solutions; versatile for various nanostructures. | Iron Oxide, ZnO, TiO₂, MnO | Controlled morphology (nanorods, quantum dots); tunable optical and electronic properties. | Applied in biosensing, medical imaging, and therapeutics. |

Detailed Experimental Protocols for Key Methods

This protocol details an innovative modification of the Marcano method, using air nanobubbles to enhance the surface area and porosity of graphene oxide.

- Reagents and Materials: Graphite flakes, Sulfuric acid (H₂SO₄, 98%), Phosphoric acid (H₃PO₄), Potassium permanganate (KMnO₄, 99%), Hydrogen peroxide (H₂O₂, 30%), Ultrapure water containing air nanobubbles (generated by counterflow hydrodynamic cavitation), Hydrochloric acid (HCl, 37%).

- Procedure:

- Acid Mixing: Combine H₂SO₄ and H₃PO₄ in a 9:1 (v/v) ratio.

- Graphite Addition: Add graphite flakes to the acid mixture.

- Oxidation: Slowly add KMnO₄ (1:6 wt. ratio to graphite) in small portions, which will cause an exotherm to 40–50°C. Heat the mixture to 50°C in a temperature-controlled water bath and stir for 12 hours. The mixture will become a paste.

- Nanobubble Incorporation: Add ultrapure water containing air nanobubbles to the paste and stir for an additional 30 minutes.

- Reaction Termination: Pour in 30 wt% H₂O₂, which changes the color to bright yellow as it reduces residual manganese ions to soluble salts.

- Work-up: Wash the resulting GO product with 200 mL of HCl (37%), followed by repeated washes with distilled water until the supernatant reaches pH ~6.

- Drying: Freeze-dry the purified GO for 48 hours.

This in chemico methodology identifies the nature, number, and reactivity of surface sites on engineered nanomaterials (ENMs) using probe molecules, providing a refined dose metric for toxicology and catalysis.

- Reagents and Materials: Powdered ENMs (e.g., ZnO, CuO, TiO₂, CeO₂, SiO₂), Methanol, SiC (inert diluent).

- Equipment: Fixed-bed reactor, Temperature Programmed Surface Reaction (TPSR) setup, Simultaneous Thermal Analyzer (for screening stability).

- Procedure:

- Sample Preparation: Mix 100–250 mg of the NM powder with 0.5 g of SiC and load it into a fixed-bed reactor.

- Methanol Chemisorption: Expose the sample to methanol at 100°C (or 50°C for highly reactive materials like CuO and ZnO). This results in the release of water molecules and the formation of methoxy species (–OCH₃) bonded to reactive surface sites.

- Temperature Programmed Surface Reaction (TPSR): Heat the sample linearly while monitoring reaction products. The nature of the released products indicates the type of surface sites:

- Acidic sites yield dimethyl ether (CH₃OCH₃).

- Redox sites generate formaldehyde (HCHO).

- Basic sites or highly reactive redox sites produce carbon dioxide (CO₂).

- Data Analysis: Quantify the reactive site surface density based on the product evolution profiles.

This protocol creates well-defined interfaces between copper and metal oxides to study their stability and reactivity in the electrochemical CO₂ reduction reaction.

- Reagents: Copper(I) acetate (Cu(I)OAc, 98%), tri-n-octylamine, oleic acid, tetradecylphosphonic acid, metal precursors (e.g., tetrakisdimethylamidozirconium, tetrakisdimethylamidotitanium, cyclopentadienyl magnesium), toluene, hydrogen peroxide (50%), 1,4-dioxane, ethanol.

- Procedure:

- Synthesis of Cu Nanocrystals: Synthesize and oxidize Cu nanospheres or nanocubes according to established methods.

- Preparation for c-ALD: Dilute a known quantity (e.g., 20 μmol) of oxidized Cu nanocrystals in anhydrous toluene in a scintillation vial under a nitrogen atmosphere.

- Precursor Preparation: In a glovebox, prepare dilute solutions of the desired metal precursor and water (as the oxygen source) in toluene and dioxane, respectively.

- Shell Growth (Titration): Using a syringe pump, co-titrate the metal precursor and water solutions slowly into the Cu nanocrystal dispersion. This step is performed sequentially with dilute and more concentrated solutions to build the oxide shell controllably.

- Reaction Termination: Inject an oleic acid solution to coordinate any unreacted metal precursor.

- Isolation and Purification: Isolate the core-shell nanoparticles by adding ethanol to induce precipitation, followed by centrifugation. Redisperse the final product in toluene.

Visualization of Synthesis and Characterization Workflows

Workflow for Nanobubble-Assisted GO Synthesis and Characterization

Workflow for Surface Site Reactivity Quantification

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

The following table details key reagents and materials essential for executing the advanced synthesis and characterization protocols described in this guide.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for Oxide Synthesis

| Reagent/Material | Function in Synthesis/Characterization | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| Potassium Permanganate (KMnO₄) [33] | Strong oxidizing agent for introducing oxygen-containing functional groups. | Oxidation of graphite in graphene oxide synthesis. |

| Air Nanobubbles (NBs) [33] | Act as templates to create microporosity and enhance exfoliation efficiency. | Boosting surface area and oxygen content in GO@NBs synthesis. |

| Methanol (CH₃OH) [22] | Probe molecule for chemisorption; identifies and quantifies reactive surface sites. | Temperature Programmed Surface Reaction (TPSR) on engineered nanomaterials. |

| Metal-organic Precursors (e.g., Tetrakis(dimethylamido)zirconium) [34] | High-purity molecular sources for metal oxides in vapor-phase deposition. | Growth of ZrOx shells on Cu nanoparticles via colloidal ALD. |

| Niobium Oxide (Nb₂O₅) Nanoparticles [35] | Heterogeneous catalyst with water-tolerant Brønsted and Lewis acid sites. | Catalyzing condensation and esterification of biomass-derived furfural. |

| Dipyridyldithiocarbonate (DPDTC) [35] | Environmentally responsible reagent leading to esters and thioesters. | Green synthesis of pharmaceutical intermediates like nirmatrelvir. |

The study of oxide surfaces is a cornerstone of advanced materials science, with critical implications for catalysis, energy storage, and semiconductor technology. Understanding surface properties—including composition, structure, chemical bonding, and thermal stability—requires a multifaceted analytical approach. Among the extensive suite of characterization techniques available, four have emerged as fundamental to this research domain: X-ray Photoelectron Spectroscopy (XPS), X-ray Diffraction (XRD), Raman Spectroscopy, and Thermogravimetric Analysis (TGA). Each technique provides distinct and complementary insights into material properties, enabling researchers to develop a comprehensive understanding of oxide surfaces.

This guide provides an objective comparison of these four core techniques, framing their performance within the specific context of oxide surface characterization. The analysis is supported by experimental data and detailed methodologies to assist researchers, scientists, and development professionals in selecting the optimal techniques for their specific research questions. By comparing their fundamental principles, capabilities, limitations, and synergistic applications, this guide aims to equip practitioners with the knowledge needed to effectively leverage this core characterization toolkit.

X-ray Photoelectron Spectroscopy (XPS)

X-ray Photoelectron Spectroscopy is a powerful surface-sensitive technique used to determine the elemental composition, empirical formula, chemical state, and electronic state of elements within a material. Its principle of operation is based on the photoelectric effect. When a material is irradiated with X-rays, electrons are ejected from the inner shells of the atoms. The kinetic energy of these photoelectrons is measured, allowing the calculation of their binding energy, which is characteristic of each element and its chemical environment. A key advantage of XPS is its exceptional surface sensitivity, probing only the top <10 nm of a material, making it ideal for analyzing surface oxidation states and contamination [36].

X-ray Diffraction (XRD)

X-ray Diffraction is a primary technique for determining the crystal structure of crystalline materials. When a beam of X-rays strikes a crystalline sample, it is scattered by the electrons of the atoms. These scattered waves constructively interfere in specific directions, governed by Bragg's Law (nλ = 2d sinθ), to produce a diffraction pattern. This pattern serves as a fingerprint for the material's crystal structure, including lattice parameters, phase identification, and crystallite size. Unlike XPS, XRD is a bulk characterization technique, providing information about the long-range order of the material's interior as well as its surface.

Raman Spectroscopy

Raman Spectroscopy probes the vibrational, rotational, and other low-frequency modes in a molecular system. It involves irradiating a sample with monochromatic laser light, with a small fraction of this light being scattered at energies different from the incident photons. This inelastic scattering, known as Raman scattering, provides information about the molecular vibrations and phonons in the material. The resulting spectrum is highly sensitive to chemical bonding, crystal structure, phase, and molecular symmetry. It is particularly effective for identifying polymorphs and detecting disorder in crystal structures.

Thermogravimetric Analysis (TGA)

Thermogravimetric Analysis is a thermal analysis technique that measures the mass change of a material as a function of temperature or time in a controlled atmosphere. The sample is placed on a high-precision balance and subjected to a programmed temperature ramp. Mass changes occur due to processes such as dehydration, decomposition, oxidation, and combustion. The first derivative of the TGA curve (DTG) pinpoints the temperature of the maximum rate of mass change (Tmax), which is characteristic of specific thermal events. TGA is invaluable for assessing the thermal stability, composition, and decomposition profile of materials [37].

Technical Comparison and Performance Data

The following tables provide a detailed, objective comparison of the performance characteristics of the four core techniques when applied to oxide surface research. The data synthesizes standard instrument specifications and performance metrics relevant to oxide analysis.

Table 1: Core Performance Characteristics for Oxide Analysis

| Technique | Primary Information | Depth Resolution | Detection Limit | Lateral Resolution |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| XPS | Elemental composition, chemical state, empirical formula | < 10 nm [36] | ~0.1 - 1 at.% | ~3 - 10 µm (micrometer probe), ~100 nm (with specialist systems) |

| XRD | Crystalline phase identification, lattice parameters, crystallite size, stress | Micrometers to millimeters (bulk technique) | ~1 - 5 wt.% | Typically several millimeters (beam size) |

| Raman | Chemical structure, phase, crystallinity, molecular bonding, defects | ~1 µm (confocal); depends on laser penetration | Varies; can be single molecule under SERS | Sub-micrometer (diffraction-limited, ~0.5 µm) |

| TGA | Thermal stability, composition (volatiles, organics, carbon content), oxidation temperature | N/A (bulk mass measurement) | Mass change: ~0.1 µg | N/A (bulk mass measurement) |

Table 2: Operational Parameters and Sample Requirements

| Technique | Typical Sample Environment | Sample Requirements / Preparation | Key Quantitative Outputs |

|---|---|---|---|

| XPS | Ultra-high vacuum (UHV: ~10⁻⁹ mbar) | Solid, vacuum-compatible, flat preferred; minimal preparation | Atomic concentration (%), chemical shift (eV), layer thickness (with sputtering) |

| XRD | Ambient air or controlled atmosphere | Powder (fine) or flat solid surface | Phase composition (wt.%), crystallite size (nm), lattice strain |

| Raman | Ambient air, liquids, gases; can be in situ | Minimal; solids, powders, liquids; can be through transparent containers | Peak position (cm⁻¹), intensity, bandwidth; phase identification |

| TGA | Controlled atmosphere (air, N₂, O₂, Ar, etc.) | ~5-20 mg of powder or small solid piece [37] | Mass change (%, µg), Tmax (°C) [37], residual mass (%) |

Table 3: Comparative Analysis of Strengths and Limitations for Oxide Research

| Technique | Key Advantages for Oxides | Key Limitations for Oxides |

|---|---|---|

| XPS | Directly measures oxidation states and surface chemistry; quantitative without standards; high surface sensitivity ideal for thin oxide films. | Requires UHV; can cause beam damage; limited spatial resolution compared to electron microscopy; poor for light elements (H, He, Li). |

| XRD | Unambiguous phase identification; distinguishes between different oxide polymorphs (e.g., TiO₂ anatase vs. rutile); standard technique for crystal structure. | Insensitive to amorphous phases; poor for surface-specific information; low detection limit for minor phases; requires crystalline material. |

| Raman | Excellent for identifying oxide polymorphs; sensitive to crystallinity and stress; can be used for in-situ/operando studies; non-destructive. | Fluorescence can swamp signal; can cause local heating; quantitative analysis is challenging; requires high-quality spectra for reliable interpretation. |

| TGA | Quantifies hydration, carbon content, and thermal stability; determines oxidation temperature of materials like graphene vs. graphite [37]. | Only measures mass changes; does not identify evolved species without coupling to MS or FTIR; results can be heating-rate dependent. |

Experimental Protocols for Oxide Characterization

To ensure reproducible and reliable data, standardized experimental protocols are essential. The following sections detail the methodologies for each technique in the context of characterizing oxide materials.

XPS Protocol for Oxide Surface Analysis

Objective: To determine the surface elemental composition and chemical states of a metal oxide sample.

- Sample Preparation: Mount the oxide powder on a conductive adhesive tape (e.g., carbon tape) or press into an indium foil. For solid samples, ensure a clean, flat surface. Minimize atmospheric exposure before loading into the instrument to reduce adventitious carbon contamination.

- Instrument Setup: Insert the sample into the ultra-high vacuum (UHV) chamber. Use a monochromatic Al Kα X-ray source (1486.6 eV). Set the analyzer pass energy to 20-80 eV for high-resolution scans and 100-160 eV for survey scans.

- Data Acquisition:

- Acquire a survey spectrum (e.g., 0-1100 eV binding energy) to identify all elements present.

- Acquire high-resolution spectra for the core-level peaks of all detected elements (especially the metal cations and O 1s).

- Use a low-energy electron flood gun for charge compensation if the sample is an insulating oxide.

- Data Analysis:

- Calibrate the spectra using the C 1s peak of adventitious carbon at 284.8 eV.

- Identify elements from the survey spectrum.

- Fit the high-resolution peaks using appropriate software (e.g., CasaXPS, Avantage). Deconvolute the O 1s peak to distinguish between lattice oxygen (O²⁻), hydroxyl groups (OH⁻), and adsorbed water.

- Quantify atomic percentages using the peak areas and relative sensitivity factors (RSFs).

XRD Protocol for Oxide Phase Identification

Objective: To identify the crystalline phases and determine the crystallite size of an oxide sample.

- Sample Preparation: For powders, use a back-loading sample holder to ensure a flat, randomly oriented surface and minimize preferred orientation.

- Instrument Setup: Use a Bragg-Brentano geometry diffractometer with a Cu Kα radiation source (λ = 1.5406 Å). Set the voltage and current to, for example, 40 kV and 40 mA.

- Data Acquisition: Scan over a 2θ range appropriate for the material (e.g., 10° to 80° for many oxides). Use a slow scan speed (e.g., 0.5-2°/min) and a small step size (e.g., 0.02°) for good resolution.

- Data Analysis:

- Identify crystalline phases by matching the peak positions and intensities with reference patterns in the International Centre for Diffraction Data (ICDD) database.

- Determine the crystallite size using the Scherrer equation: D = Kλ / (β cosθ), where D is the crystallite size, K is the shape factor (~0.9), λ is the X-ray wavelength, β is the full width at half maximum (FWHM) of the diffraction peak in radians, and θ is the Bragg angle.

Raman Spectroscopy Protocol for Oxide Structure

Objective: To probe the molecular structure, phase, and defect nature of an oxide.

- Sample Preparation: Minimal preparation is needed. Powders can be placed on a glass slide. Ensure the surface is clean for solid samples.

- Instrument Setup: Select an appropriate laser wavelength (e.g., 532 nm or 785 nm are common). Lower wavelengths offer higher resolution but may increase fluorescence for some oxides. Set the grating to achieve the desired spectral range. Calibrate the instrument using a silicon wafer (peak at 520.7 cm⁻¹).

- Data Acquisition: Focus the laser on the sample. Set the acquisition time and number of accumulations to achieve a good signal-to-noise ratio without causing laser-induced damage (e.g., 10-30 seconds, 2-5 accumulations).

- Data Analysis:

- Pre-process the spectrum if necessary (cosmic ray removal, background subtraction).

- Identify the characteristic Raman peaks by comparing their positions to literature values for known oxide phases.

- Analyze peak shifts (indicative of stress), broadening (related to crystallite size or defects), and relative intensities.

TGA Protocol for Oxide Thermal Stability

Objective: To determine the thermal stability, composition, and oxidation behavior of an oxide or carbon-containing material [37].

- Sample Preparation: Weigh approximately 5-10 mg of powder into a clean, high-purity alumina crucible [37].

- Instrument Setup: Load the sample and an empty reference crucible. Set the gas atmosphere and flow rate (e.g., synthetic air or oxygen for oxidation studies, 60 mL/min) [37]. Program the temperature ramp (e.g., 10 °C/min from room temperature to 900-1000 °C) [37].

- Data Acquisition: Start the experiment. The instrument will record mass (TGA) and mass change rate (DTG) as a function of temperature.

- Data Analysis:

- Identify the temperature of maximum mass loss rate (Tmax) from the minimum of the DTG peak [37].

- Quantify the mass loss in each step as a percentage of the initial mass. For graphene materials, a higher Tmax value indicates greater thermal stability and can be correlated with larger particle size and graphitic character, helping distinguish graphene from graphite [37].

Synergistic Workflow for Comprehensive Oxide Analysis

The true power of this toolkit is realized when the techniques are used synergistically. A logical, integrated workflow for characterizing a novel oxide material is depicted below. This approach ensures that the limitations of one technique are compensated by the strengths of another, leading to a robust and comprehensive material analysis.

Workflow Diagram Title: Integrated Oxide Characterization Strategy

Workflow Narrative: The process typically begins with XRD and Raman spectroscopy to answer fundamental questions about the material's bulk crystal structure and molecular phase. XRD provides definitive phase identification, while Raman is sensitive to local structure and defects, often confirming or refining the XRD findings. The insights from these techniques then inform the subsequent TGA and XPS analyses. For instance, knowing the crystal phase helps interpret the thermal decomposition profile in TGA, and understanding the bulk structure provides context for the surface chemistry revealed by XPS. Finally, data from all four techniques is synthesized to build a unified and comprehensive model of the oxide material's properties, from its bulk crystal structure to its surface composition and thermal behavior.

Essential Research Reagent Solutions and Materials

Successful characterization relies on high-quality samples and consumables. The following table details key materials and their functions in the characterization workflow.

Table 4: Essential Research Materials and Consumables

| Material/Consumable | Function/Application |

|---|---|

| High-Purity Alumina Crucibles | Inert sample holders for TGA analysis, capable of withstanding high temperatures without mass change. |

| Conductive Adhesive Tapes (e.g., Carbon, Copper) | For mounting powder samples for XPS and SEM analysis to ensure electrical conductivity and stability. |

| Indium Foil | A soft, malleable metal used to mount powder samples for XPS; provides a clean, conductive background. |

| Certified Standard Reference Materials (e.g., Si, SiO₂) | Used for calibration of instruments (e.g., Raman shift using Si wafer) and validation of analytical results. |

| High-Purity Calibration Gases (e.g., Ar, N₂, O₂) | For creating controlled atmospheres in TGA and in-situ cells for other techniques. |

| ICP-MS Grade Acids | For digesting oxide samples for complementary bulk elemental analysis via ICP-MS or ICP-OES. |

| Non-Magnetic Tweezers & Sample Tools | For handling samples without introducing contamination or scratches, especially critical for surface analysis. |

Surface functionalization represents a cornerstone of modern materials science, enabling the precise modification of material interfaces to impart new, tailored properties. Within this domain, amination and metallic site grafting have emerged as two of the most powerful and widely adopted strategies. These techniques facilitate the strategic installation of functional groups and metal sites onto material surfaces, dramatically altering their chemical behavior, reactivity, and interaction capabilities. The broader thesis of comparing oxide surface properties research recognizes that the performance of functionalized materials is intrinsically linked to the chosen modification pathway. This guide provides an objective comparison of these two fundamental strategies, drawing upon current experimental data to elucidate their relative performance across biomedical, environmental, and catalytic applications, thereby offering researchers a evidence-based framework for selection and implementation.

Strategic Comparison: Amination vs. Metallic Site Grafting

The choice between amination and metallic site grafting is governed by the target application's specific requirements, including the desired surface chemistry, stability, and functionality. The table below provides a high-level comparison of these two strategies.

Table 1: Fundamental Comparison of Amination and Metallic Site Grafting

| Characteristic | Amination | Metallic Site Grafting |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Interaction | Covalent bonding, electrostatic interactions, hydrogen bonding [38] | Covalent coordination, strong ionic interactions, formation of nanometer interfaces [39] |

| Key Functional Groups | -NH₂, -NH- (from amines like PEI, TETA, APTES) [40] [38] | Metal-Oxide bonds, metal clusters (e.g., Pd, Ag, Bi) [39] [41] |

| Typical Applications | CO₂ capture, heavy metal removal, drug delivery [42] [40] [38] | Heterogeneous catalysis, photocatalysis, antimicrobial activity [39] [41] |