Precision in the Nanoscale: Mastering AFM Contact Point Determination for Accurate Nanoindentation in Biomedical Materials

This comprehensive guide details the critical process of Atomic Force Microscopy (AFM) contact point determination for nanoindentation, tailored for researchers and drug development professionals.

Precision in the Nanoscale: Mastering AFM Contact Point Determination for Accurate Nanoindentation in Biomedical Materials

Abstract

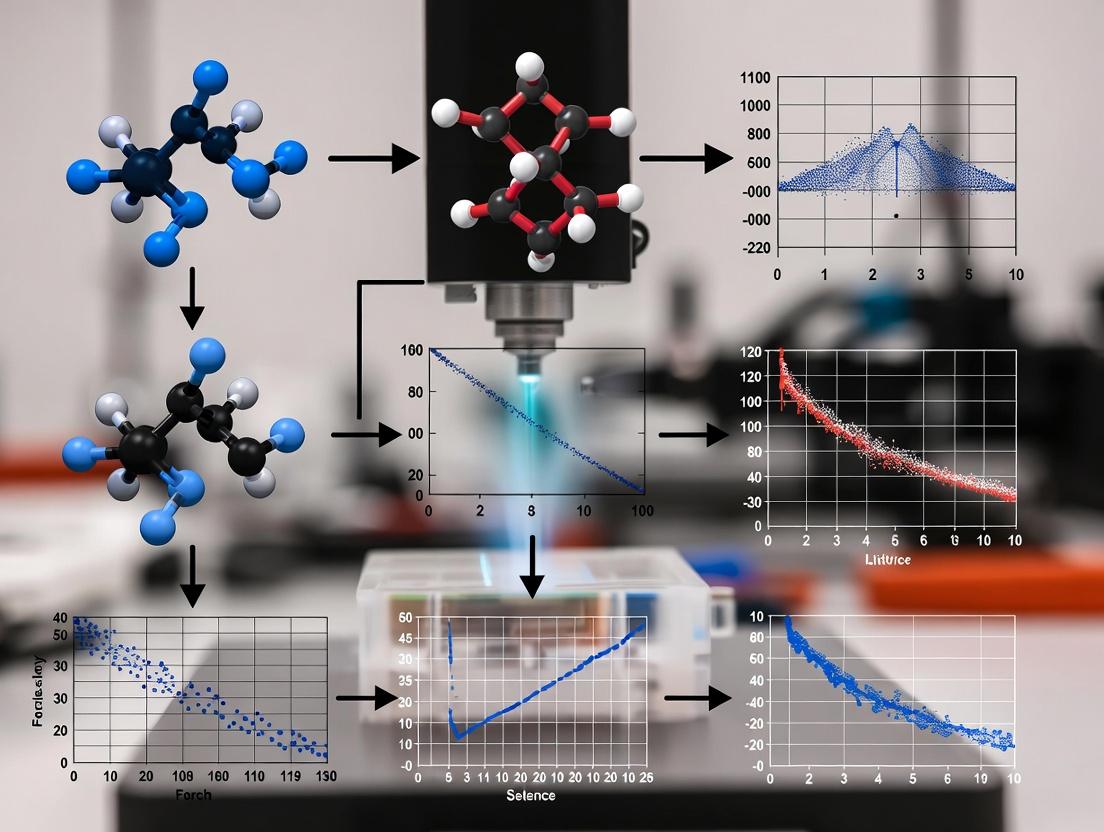

This comprehensive guide details the critical process of Atomic Force Microscopy (AFM) contact point determination for nanoindentation, tailored for researchers and drug development professionals. It explores the fundamental principles of tip-sample interaction, provides step-by-step methodological workflows for soft biological samples, addresses common troubleshooting and optimization challenges, and validates techniques through comparative analysis with other nanomechanical methods. The article bridges theoretical understanding with practical application, aiming to enhance the accuracy and reproducibility of nanomechanical property measurements in biomaterials, cells, and tissues for advanced biomedical research.

The First Touch: Foundational Principles of AFM Tip-Sample Interaction and Contact Point Physics

Troubleshooting Guides & FAQs

Q1: Why is my force curve showing a significant vertical shift before contact, and how does this affect contact point determination?

A: A vertical shift, or "force offset," is often caused by electrostatic forces, laser interference, or a misaligned photodetector. It directly skews the baseline, leading to an erroneous contact point. This is critical for accurate modulus calculation.

Protocol for Correction:

- In a non-contact region of the curve, fit a linear function to the baseline.

- Subtract this function from the entire force dataset to zero the baseline.

- Ensure the measurement is performed in a controlled humidity environment or in liquid to minimize electrostatic and meniscus forces.

Q2: My indentation data shows high variability in calculated modulus on the same sample. Could contact point uncertainty be the cause?

A: Yes, this is a primary symptom. A variation of just 1-2 data points in contact point assignment can lead to modulus variations exceeding 50%, especially on soft materials.

Protocol for Improved Consistency:

- Data Collection: Increase the sampling resolution (points/nm) during approach.

- Algorithmic Determination: Use a standardized algorithm. The "threshold method" is common: define the contact point as the point where the force deflection exceeds a set multiple (e.g., 5x) of the standard deviation of the baseline noise.

- Validation: Visually inspect the algorithm-selected points on a subset of curves to ensure they align with the observed deflection onset.

Q3: How do I choose between contact point determination algorithms (e.g., threshold, linear fit, extrapolation) for my biological sample?

A: The choice depends on sample stiffness and data quality. See the comparison table below.

Table 1: Comparison of Contact Point Determination Methods

| Method | Principle | Best For | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Visual Inspection | User manually selects point. | Training, simple datasets. | Irreproducible, user-biased. |

| Threshold Method | Contact when force > N*σ (noise). | High-SNR data, standard materials. | Sensitive to baseline noise. |

| Linear Fit | Fits lines to baseline & contact slope; intersection is contact point. | Curves with clear linear elastic regions. | Fails on non-linear initial contact. |

| Extrapolation Method | Fits a function (e.g., polynomial) to the indentation data and extrapolates to zero force. | Compliant samples (cells, hydrogels). | Assumes a material model. |

Protocol for Algorithm Testing:

- Apply 2-3 different methods to the same dataset.

- Calculate the derived elastic modulus for each.

- Compare the coefficient of variation (CV) for each method across multiple curves. The method yielding the lowest CV for your sample type is optimal.

Q4: What are the key instrumental factors that can obscure the true contact point in nanoindentation of live cells?

A: The main factors are thermal drift, low signal-to-noise ratio (SNR), and hydrodynamic drag in liquid.

Protocol for Minimization:

- Thermal Drift: Allow the microscope and stage to equilibrate for at least 45-60 minutes. Use a closed-loop scanner if available. Calculate drift rate before experiment and correct data.

- Low SNR: Use softer cantilevers (low spring constant) for higher deflection sensitivity. Increase laser intensity (without saturating the detector) and adjust photodetector alignment.

- Hydrodynamic Drag: Use a blunted or spherical probe to reduce drag. Set a lower approach/retract velocity. Apply a drag correction model by fitting the non-contact portion of the approach curve in liquid.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent & Material Solutions

Table 2: Essential Materials for Reliable AFM Nanoindentation

| Item | Function & Rationale |

|---|---|

| Tipless Cantilevers | The base for attaching custom colloidal probes (e.g., silica beads), providing defined geometry for Hertz model fitting. |

| Silicon Nitride Spherical Tips (5-20μm radius) | Provides a known, symmetric indenter geometry critical for quantitative modulus measurement on soft, heterogeneous samples. |

| Calibration Grid (TGZ1, etc.) | For precise lateral calibration of the piezoelectric scanner, ensuring accurate indentation depth and sample positioning. |

| Reference Sample (PDMS, Agarose Gel) | A soft material with known, homogeneous elastic properties. Used to validate the entire measurement and analysis protocol. |

| BSA (Bovine Serum Albumin) Solution (1% w/v) | Used to passivate the probe/colloid surface to minimize non-specific adhesive forces that complicate contact point detection. |

| Liquid Cell with Temperature Control | Enables physiologically relevant measurements on live cells or biomaterials and minimizes thermal drift through stabilization. |

Experimental Workflow for Robust Contact Point Determination

Workflow for Contact Point Determination in AFM Nanoindentation

Algorithm Selection Logic for Contact Point Detection

Decision Tree for Selecting a Contact Point Algorithm

This technical support center is framed within the context of a broader thesis on precise Atomic Force Microscopy (AFM) contact point determination for nanoindentation research. Accurate identification of the contact point is critical for deriving meaningful mechanical properties such as elastic modulus and hardness. The following guides address common experimental challenges.

Troubleshooting Guides & FAQs

Q1: During the approach segment, my curve shows an erratic "snap-to-contact" jump before the expected linear region. What causes this and how can I mitigate it?

A: This is typically caused by attractive forces (van der Waals, capillary) between the tip and sample. It leads to premature, uncontrolled contact and inaccurate contact point determination.

- Solution: Reduce the relative humidity in the measurement chamber to below 30% to minimize the capillary water meniscus. Use a tip with a lower spring constant (k) to reduce the jump magnitude, but ensure k is still high enough for controlled indentation. Employ a "soft landing" protocol by reducing the approach velocity.

Q2: The contact region of my force curve is non-linear from the onset, making it impossible to define a clear contact point for nanoindentation analysis. What's wrong?

A: A non-linear initial contact usually indicates sample or tip contamination, or a sample that is too soft for the tip stiffness.

- Solution:

- Clean the tip and sample using appropriate protocols (e.g., UV-ozone treatment, solvent cleaning).

- Verify tip shape and integrity via scanning electron microscopy (SEM) before and after experiments.

- For very soft samples (e.g., cells, hydrogels), ensure you are using a tip with a spring constant orders of magnitude lower than the sample's expected stiffness. Calibrate the tip's sensitivity on a hard, clean surface (e.g., sapphire) before each experiment.

Q3: In the retract segment, I observe significant adhesion hysteresis (the retract curve is far below the approach curve). How does this affect nanoindentation data and how can it be quantified?

A: Adhesion hysteresis complicates the determination of the zero-force baseline upon retraction, affecting the calculation of dissipated energy and recovery. It is critical to report for viscoelastic or plastic materials.

- Solution: Quantify the adhesion by measuring the minimum force value on the retract curve (adhesion force, F_adh) and the area between the approach and retract curves (dissipation energy). Use the following table to document these parameters:

| Parameter | Symbol | Determination Method | Impact on Nanoindentation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Adhesion Force | F_adh | Minimum force value on retract curve. | Overestimates applied load during approach; affects stress calculations. |

| Dissipation Energy | E_diss | Area enclosed between approach and retract curves. | Indicates plastic deformation or viscous losses; crucial for soft material analysis. |

| Pull-off Distance | d_po | Horizontal distance from contact point to adhesion minimum. | Related to material tackiness and tip-sample interaction range. |

Q4: My force curves show inconsistent contact points across different locations on the same sample. How can I improve reproducibility?

A: This points to sample surface heterogeneity, drift, or thermal noise.

- Solution Protocol:

- Thermal Equilibrium: Allow the AFM and sample to equilibrate in the environment for at least 30-60 minutes before measurement.

- Drift Compensation: Implement a drift compensation routine if available. Reduce data acquisition time per curve.

- Surface Mapping: First, perform a low-force topographic scan to identify regions of interest and avoid obvious contaminants or uneven areas.

- Statistical Rigor: Acquire a large number of curves (n > 50) across multiple samples. Apply a consistent, algorithmic contact point detection method (e.g., using the deviation from the non-contact baseline by a threshold, typically 3-5 times the noise standard deviation).

Experimental Protocol: Algorithmic Contact Point Determination for Nanoindentation

Objective: To programmatically and reproducibly identify the contact point (z₀) from a force-distance curve for subsequent nanoindentation analysis.

Materials & Reagents:

Research Reagent Solutions & Essential Materials

| Item | Function |

|---|---|

| AFM with Liquid Cell | Enables force spectroscopy in controlled fluid environments (e.g., PBS for biological samples). |

| Nitrogen Gas Dryer | Reduces humidity to minimize capillary forces during air measurements. |

| Calibration Grating (e.g., Sapphire) | Provides an infinitely hard, smooth surface for precise photodetector sensitivity (InvOLS) calibration. |

| Colloidal Probe Tips | Tips with spherical termini (diameter 1-10 µm) for well-defined Hertzian contact mechanics on soft materials. |

| UV-Ozone Cleaner | Removes organic contaminants from tips and sample substrates prior to measurement. |

| Vibration Isolation Table | Mitigates environmental noise that obscures the true contact point signal. |

Methodology:

- Calibration: Calibrate the cantilever spring constant (k) using the thermal tune method. Calibrate the optical lever sensitivity (InvOLS) on a clean, hard calibration surface.

- Data Acquisition: Acquire force-distance curves at a set velocity suitable for the material (typically 0.5-2 µm/s for soft matter to avoid hydrodynamic effects).

- Pre-processing: Flatten the non-contact portion of the approach curve to define a zero-force baseline.

- Algorithm Application:

- Calculate the standard deviation (σ) of the force signal in the non-contact region.

- Define a contact threshold, e.g., 5σ.

- Scan the approach curve data from left to right (approach direction). The contact point (z₀) is the first z-piezo position where the deflection signal consistently exceeds the ±5σ band.

- Visually verify the algorithm's selection on a subset of curves.

- Data Transformation: Transform the x-axis from piezo displacement (z) to tip-sample separation (δ) and then to indentation depth (δ) by subtracting z₀. The force (F) is k × deflection (d).

Visualization: Force-Distance Curve Analysis Workflow

Title: AFM Contact Point Determination Workflow for Nanoindentation

Title: Force-Distance Curve Segments Deconstructed

Technical Support & Troubleshooting Center

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: During AFM approach, my force curve shows an abrupt "jump-to-contact" before the expected repulsive wall. What force is causing this and how can I mitigate it? A: This is typically caused by dominant attractive forces, most often capillary forces from a liquid meniscus. To mitigate:

- Perform experiments in a controlled humidity environment (<10% RH) or an inert liquid cell.

- Use hydrophobic probes and samples to minimize water layer adsorption.

- Increase the stiffness of your cantilever to resist the attractive pull.

Q2: My indentation modulus values are inconsistent between runs on the same sample. I suspect adhesion hysteresis. How do I isolate and account for capillary force? A: Capillary force can vary with humidity and time. Implement this protocol:

- Calibrate the AFM cantilever spring constant and photodetector sensitivity in the same medium as your experiment.

- Measure Force-Distance Curves at a minimum of three controlled humidity levels (e.g., <10%, 40%, 70% RH) using an environmental chamber.

- Plot the adhesion force (pull-off force) vs. Relative Humidity. The y-intercept (at 0% RH) gives the adhesion force component without capillary contribution (primarily van der Waals).

- Use this baseline adhesion value in your contact models (e.g., DMT, JKR) for more consistent modulus calculation.

Q3: For a charged biological sample in buffer, how do I distinguish electrostatic double-layer forces from the repulsive contact force? A: Electrostatic forces are long-range (tens of nm), while repulsive contact is short-range (<1-2 nm). To distinguish:

- Vary Ionic Strength: Perform approach curves in buffers with different NaCl concentrations (e.g., 1 mM, 10 mM, 150 mM). Higher ionic strength compresses the double layer, shifting the electrostatic onset to shorter ranges. If the onset distance decreases with increasing ionic strength, it confirms an electrostatic component.

- Fit the Data: Use a DLVO theory model to fit the non-contact portion of the curve and subtract it to isolate the pure repulsive contact interaction.

Q4: What is the best method to precisely determine the "true" mechanical contact point from a force curve with significant adhesion? A: The contact point is ambiguous with adhesion. Follow this analytical workflow:

- Acquire high-resolution force curves on a stiff, non-deformable reference sample (e.g., sapphire) to characterize your probe's exact non-linear repulsive wall profile.

- On your soft sample, fit the repulsive portion of the approach curve after the jump-to-contact using a contact mechanics model (e.g., Hertz).

- Extrapolate this fit curve back to the zero-force line. The intersection point is often a more reliable operational definition of mechanical contact for nanoindentation analysis than the point where the force first becomes non-zero.

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue: Unstable AFM Cantilever Oscillation in Liquid During Force Mapping

- Symptoms: Erratic amplitude/phase signal, impossible to engage or track the surface reliably.

- Likely Culprit: Hydrodynamic drag and fluctuating electrostatic/capillary forces from ionic concentrations.

- Solution Steps:

- Use cantilevers designed for liquids (shorter, stiffer).

- Allow the probe and liquid cell to thermally equilibrate for 30+ minutes.

- Reduce the drive amplitude and increase the setpoint ratio.

- Use a lower scan rate for force volume imaging.

- Consider using frequency modulation (FM) mode instead of amplitude modulation if available, as it is less sensitive to dissipative forces.

Issue: Adhesion Force Measurements Show High Variability on a Supposedly Homogeneous Polymer Surface

- Symptoms: Large standard deviation in pull-off force across a force volume map.

- Likely Culprit: Contamination or changing tip chemistry (aging), altering van der Waals and capillary interactions.

- Solution Steps:

- Clean the Tip: Perform UV-ozone cleaning for 15-20 minutes before experiments.

- Characterize the Tip: Perform an adhesion map on a clean, standardized sample (e.g., freshly cleaved mica) before and after your experiment to check tip stability.

- Control Environment: Use an inert gas purge or vacuum if possible.

- Functionalize the Tip: Apply a consistent self-assembled monolayer (e.g., alkanethiol on a gold-coated tip) for chemically well-defined interactions.

Quantitative Force Comparison Table

| Force Type | Typical Range (from surface) | Magnitude (for typical AFM tip) | Sign (Attractive/Repulsive) | Dominant Environmental Factor |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| van der Waals | 0.3 - 10 nm | 0.1 - 10 nN | Attractive | Material dielectric properties, tip geometry |

| Electrostatic | 1 - 100 nm | 0.01 - 1 nN | Attractive or Repulsive | Surface potential, ionic strength of medium |

| Capillary | 0 - 5 nm (meniscus bridge) | 1 - 100 nN | Strongly Attractive | Relative Humidity (>25%) |

| Repulsive Contact | 0 - 0.2 nm (interatomic) | Exponentially rises (0 to >100 nN) | Repulsive | Material elasticity, indentation depth |

Experimental Protocol: Isolating Capillary Force Contribution

Objective: Quantify the capillary force component of total adhesion as a function of relative humidity (RH). Materials: AFM with environmental chamber, silicon nitride tip, clean silicon wafer sample, humidity sensor. Procedure:

- Mount the tip and sample. Calibrate the cantilever in air.

- Seal the environmental chamber. Set the humidity generator to 5% RH. Allow 30 minutes for stabilization.

- At the sample center, acquire 100 force-distance curves at a 0.5 Hz approach/retract rate and 500 nm z-range.

- Systematically increase the RH to 20%, 40%, 60%, and 80%, repeating step 3 at each level.

- For each curve, measure the pull-off adhesion force (

F_ad). - Calculate the mean

F_adat each RH level. - Plot

F_advs.RH. The linear slope indicates the sensitivity of adhesion to capillary forces. The intercept at 0% RH estimates the van der Waals contribution.

Diagram: AFM Contact Point Determination Workflow

Title: Workflow for Determining AFM Mechanical Contact Point

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents & Materials

| Item | Function in Experiment |

|---|---|

| Silicon Nitride AFM Probes | Standard probe for force spectroscopy. Biocompatible, well-defined geometry for contact mechanics models. |

| Gold-Coated Cantilevers | Allows for functionalization with thiolated chemical or biological ligands via self-assembled monolayers (SAMs). |

| Cleanroom-Grade Silicon Wafers | Atomically flat, chemically inert reference sample for probe calibration and cleaning validation. |

| Phosphate Buffered Saline (PBS) Tablets | For preparing biologically relevant ionic solutions of consistent molarity for electrostatic force control. |

| Alkanethiols (e.g., 1-Octadecanethiol) | Used to create hydrophobic, chemically uniform monolayers on gold-coated tips to standardize van der Waals interactions. |

| UV-Ozone Cleaner | Critical for removing organic contaminants from AFM tips and samples to ensure reproducible forces. |

| Environmental Chamber w/ Humidity Control | Enables precise control of relative humidity (5%-95% RH) to quantify and eliminate capillary forces. |

| Colloidal Probe Kits | Tips with a micron-sized silica or polymer sphere attached; provide a well-defined, spherical geometry for quantitative adhesion and modulus measurement. |

Why Contact Point Accuracy is Non-Negotiable for Young's Modulus Calculation

In Atomic Force Microscopy (AFM) nanoindentation for materials science and biomolecular research, the accurate determination of the contact point between the probe tip and the sample surface is the foundational step for deriving accurate mechanical properties, most critically Young's modulus. An error of a few nanometers in identifying this point propagates exponentially into the calculated modulus, rendering data unreliable. This technical support center provides targeted guidance for researchers encountering these critical experimental challenges.

Troubleshooting Guides & FAQs

Q1: My calculated Young's modulus values show high variability (>50% standard deviation) between repeated indents on the same homogeneous polymer sample. What is the primary cause? A: This is overwhelmingly indicative of inconsistent or erroneous contact point determination. The force-distance curve's non-contact and contact regions must be precisely distinguished. Variability often stems from: 1) Excessive noise obscuring the deflection onset, 2) Incorrect assumption of a "zero" deflection baseline due to drift, or 3) An overly simplistic algorithm (e.g., simple threshold) for automatic detection on a viscoelastic sample.

Q2: When indenting very soft samples like hydrogels or live cells, the contact region appears gradual, making a definitive "point" hard to identify. How should I proceed? A: Soft samples exhibit a gradual compliance due to their high adhesiveness and porosity. Avoid methods relying on a sharp kink. Instead, use:

- Two-Point Method: Fit two separate linear regressions—one to the non-contact (baseline) and one to the linear portion of the contact region. The contact point is the intersection of these two lines.

- Regression-Based Analysis: Use a script to iteratively fit the contact portion, extrapolate to zero deflection, and identify the intersection with the baseline. This is more robust for noisy data.

Q3: My AFM software's automated contact point detection yields different modulus values than when I manually select the point. Which should I trust? A: Manual verification is always required. Automation can fail due to local thermal drift, adhesive dips, or surface contamination. The protocol is:

- Record a high-resolution force curve with sufficient points in the approach segment.

- Let the algorithm provide a first estimate.

- Visually inspect every curve to confirm the algorithm's point aligns with the unambiguous onset of repulsive force. Reject or correct curves where it does not.

- For batch processing, apply a consistent manual correction offset based on your visual assessment criteria.

Q4: How does thermal drift specifically impact contact point accuracy, and how can I quantify and correct for it? A: Thermal drift causes the piezo position and the sample's relative height to change over time, shifting the apparent contact point. It is critical for long-duration maps on cells or in varying ambient conditions.

- Quantification: Perform a "hold" segment at a setpoint force before retraction. The drift rate (nm/s) is calculated from the change in piezo position required to maintain constant deflection during this hold.

- Correction Protocol:

- Incorporate a 1-2 second hold period at a low setpoint force in your force curve recipe.

- Measure the slope of the piezo displacement during the hold.

- Subtract the drift-displacement (drift rate * time from start of curve to contact) from the raw piezo extension data before contact point analysis.

Data Presentation: Impact of Contact Point Error on Calculated Young's Modulus

The following table quantifies the percentage error in Young's Modulus (E) resulting from a systematic overestimation of the contact point (δ) for a theoretical spherical indentation on a sample with a true E = 10 kPa. Calculations are based on the Hertz model.

Table 1: Error Propagation from Contact Point Inaccuracy

| Contact Point Error (δ) | Assumed Indentation Depth (δ) | Calculated E (kPa) | Percentage Error in E |

|---|---|---|---|

| +0 nm | 100 nm | 10.0 | 0% |

| +10 nm | 90 nm | 7.4 | -26% |

| +20 nm | 80 nm | 5.6 | -44% |

| +30 nm | 70 nm | 4.3 | -57% |

| -10 nm | 110 nm | 13.5 | +35% |

Note: Negative δ error (early contact detection) inflates E, while positive δ error (late detection) reduces E. The relationship is non-linear and model-dependent.

Experimental Protocols

Protocol: Reliable Contact Point Determination for Heterogeneous Biological Samples Objective: To consistently identify the probe-sample contact point in force-volume maps of living cells or tissue sections. Materials: As per "The Scientist's Toolkit" below. Method:

- Pre-Approach: Engage the probe in contact mode at a negligible force (<100 pN) on a rigid, clean area (e.g., glass substrate adjacent to the cell).

- Baseline Stabilization: Before each force curve, pause for 200 ms to allow vibrational damping and record the baseline cantilever deflection (in volts).

- Data Acquisition: Execute the approach curve with a piezo velocity ≤ 1 µm/s and a sampling rate ≥ 2 kHz to capture sufficient data points near contact.

- Offline Analysis (Algorithm): a. Smoothing: Apply a 3rd-order Savitzky-Golay filter (window: 5-15 points) to the raw deflection vs. Z-piezo data. b. Baseline Fit: Fit a linear regression to the top 20% of the approach curve (clearly non-contact region). c. Deviation Detection: Calculate the standard deviation (σ) of the residuals from the baseline fit. Define the contact threshold as the point where the smoothed deflection signal deviates by more than 5σ from the extrapolated baseline. d. Visual Validation: Overlay the detected point on the raw data for 20-30 randomly selected curves per map. Accept or manually adjust.

Mandatory Visualization

Title: Contact Point Determination Workflow

Title: Error Propagation from CP Inaccuracy

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Materials for AFM Nanoindentation Accuracy

| Item | Function & Importance for Contact Point Accuracy |

|---|---|

| Calibrated AFM Cantilevers (e.g., MLCT-Bio, HQ:NSC) | Precise spring constant (k) calibration via thermal tune is mandatory. An error in k directly corrupts the force signal, shifting the apparent contact point. |

| Rigidity Calibration Grid (e.g., TGT1, PDMS arrays) | Provides an ultra-rigid, flat surface for in-situ deflection sensitivity calibration. Must be done daily/experimentally to convert Volts to nanometers. |

| Anti-Vibration Table & Acoustic Enclosure | Minimizes environmental noise that obscures the subtle deflection change at contact, especially on soft samples. |

| Temperature & Humidity Monitor | Allows for tracking environmental drift sources. Essential for correcting thermal drift in piezo displacement. |

| Standard Reference Samples (e.g., Polystyrene, Polyacrylamide gels of known E) | Positive controls to validate the entire workflow—from contact point detection to model fitting—before testing unknown samples. |

| High-Quality Liquid Cell (for biological samples) | Ensures stable immersion without bubbles or leaks, preventing drift and false deflection signals. |

Technical Support Center: Troubleshooting AFM Contact Point Determination

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: My force curves show a large vertical offset before contact. What is causing this and how do I correct it? A1: A large vertical offset is often due to a thermal drift or a laser spot misalignment on the photodetector. First, ensure the AFM is thermally equilibrated (allow 1-2 hours after laser turn-on). Realign the laser to the center of the cantilever and maximize the sum signal. Then, perform a photodetector sensitivity calibration on a rigid sample (e.g., sapphire) to establish a correct baseline.

Q2: The calculated Young's modulus varies dramatically between repeat indentations on the same sample. Could this be a contact point issue? A2: Yes, inconsistent contact point identification is a primary cause of modulus variability. This is often due to surface contamination or adhesive interactions. Implement an automated contact point algorithm (e.g., using the deviation threshold method with a noise band of 2-3 times the baseline RMS) and visually inspect each curve to validate the chosen point. Clean the sample and tip with appropriate solvents (e.g., ethanol, IPA) to reduce adhesion.

Q3: How do I distinguish a real surface contact from a nanobubble or a contaminant event in a liquid environment? A3: Nanobubbles and contaminants typically produce a "step" or a non-linear repulsion before the expected linear region. To troubleshoot, increase the approach speed temporarily to pierce through bubbles. Use sharper tips with higher aspect ratios. Filter buffers using a 0.02 µm filter and degas liquids before injection. A control experiment on a known, hard sample in liquid is essential.

Q4: My data shows negative indentation depths. What does this mean and how do I fix it? A4: Negative indentation depths directly indicate that the contact point has been set too late (i.e., into the repulsive wall of the force curve). Re-analyze your data by setting the contact point at the first sustained deviation from the non-contact baseline. Use a dual-criteria method: 1) Deflection signal exceeds 3σ of the baseline noise, and 2) The slope of the deflection vs. piezo displacement increases consistently over the next 5-10 data points.

Experimental Protocols for Validating Contact Point Determination

Protocol 1: Baseline Noise Characterization and Threshold Determination

- Objective: Quantify baseline noise to set a statistically valid contact detection threshold.

- Method: a. Retract the tip at least 2 µm from the surface. b. Record the deflection signal at a high data rate (e.g., 10 kHz) for 1 second. c. Calculate the Root Mean Square (RMS) noise of this baseline signal. d. Repeat this 5 times at different locations to establish a mean noise level. e. Set the contact threshold to Mean Baseline Noise + (3 × RMS). This value should be used in your automated detection script.

Protocol 2: Systematic Comparison of Contact Point Algorithms on a Reference Sample

- Objective: Evaluate the accuracy and precision of different algorithms.

- Method: a. Use a sample of known, homogeneous modulus (e.g., polydimethylsiloxane, PDMS, of a certified stiffness). b. Acquire a matrix of 100 force curves (10x10) with a set maximum load. c. Process the identical dataset using four common methods: i. Visual/manual selection. ii. Threshold method (from Protocol 1). iii. Linear fit intersection (fit baseline and contact region, find intersect). iv. Sensitivity method (find point where deflection/piezo slope changes). d. For each method, calculate the derived Young's modulus and its coefficient of variation (CV). The method yielding the lowest CV for the known sample is optimal for your system/sample type.

Data Presentation

Table 1: Impact of Contact Point Error on Calculated Young's Modulus (Simulated Data for a 10 kPa Sample)

| Contact Point Error (nm) | Apparent Indentation Depth Error (%) | Calculated Apparent Modulus (kPa) | Error in Modulus (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| -20 (Late) | +25 | 5.6 | -44 |

| -10 (Late) | +12.5 | 8.1 | -19 |

| 0 (Correct) | 0 | 10.0 | 0 |

| +10 (Early) | -12.5 | 12.9 | +29 |

| +20 (Early) | -25 | 17.0 | +70 |

Table 2: Comparison of Contact Point Algorithm Performance on PDMS (5 MPa)

| Algorithm | Mean Calculated Modulus (MPa) | Standard Deviation (MPa) | Coefficient of Variation (%) | Average Processing Time per Curve (ms) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Visual/Manual | 5.05 | 0.21 | 4.2 | 5000 |

| Threshold (5×RMS) | 5.12 | 0.38 | 7.4 | 50 |

| Linear Intersection | 4.98 | 0.19 | 3.8 | 75 |

| Sensitivity Change | 5.20 | 0.45 | 8.7 | 60 |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

| Item | Function & Rationale |

|---|---|

| Sapphire Disc (Reference Sample) | An atomically smooth, infinitely rigid substrate for calibrating the photodetector sensitivity (InvOLS) and checking tip health. |

| Certified PDMS Elastomer Kit | A reference material with known, homogeneous Young's modulus (range 0.1 kPa to 3 MPa) for validating contact point algorithms and calibration workflow. |

| Silicon Nitride Tips (MLCT-Bio) | Soft cantilevers (low spring constant, ~0.01-0.1 N/m) for biological samples. Their low stiffness maximizes deflection signal for accurate contact detection. |

| Sharpened Tips (e.g., ScanAsyst-Fluid+) | High-aspect-ratio tips designed for liquid operation to minimize nanobubble formation and pierce through surface layers. |

| 0.02 µm Anodized Filter | For filtering all buffers and solutions to remove particulate contaminants that can cause false contact events or tip contamination. |

| Plasma Cleaner (Low-Power) | For rigorously cleaning silicon-based tips and substrates to remove organic contaminants and ensure a hydrophilic surface in liquid experiments. |

Mandatory Visualizations

Title: Workflow for Contact Point Impact on Modulus

Title: Threshold Contact Point Algorithm

From Theory to Lab Bench: Step-by-Step Methodologies for Reliable Contact Point Detection

Troubleshooting Guides & FAQs

Q1: During the calibration of the photodetector sensitivity (InvOLS), the obtained value seems inconsistent between calibration runs. What could be the cause? A: Inconsistent InvOLS calibration often stems from a non-linear photodetector response or laser drift. First, ensure the laser spot is centered on the cantilever and the photodetector sum signal is maximized and stable. Perform the calibration on a clean, hard area (e.g., sapphire or freshly cleaved mica) to avoid sample compliance. Use a thermal tune to find the cantilever's resonant frequency and ensure you are using the correct spring constant. Limit the trigger force during calibration to 1-5 nN. Perform the calibration at multiple locations on the sample and average the results.

Q2: After a laser realignment, the photodetector signal is saturated even at minimum gain. How do I resolve this? A: This indicates the laser spot is positioned incorrectly on the photodetector quadrant. Gradually reduce the laser power from the source, if possible. Using the alignment screws, deliberately move the laser spot off the photodetector center until the signal is no longer saturated. Then, slowly re-center it, ensuring the vertical and horizontal difference signals are zero when the cantilever is undeflected (free air). The sum signal should be between 3-6 V for optimal sensitivity.

Q3: The thermal noise spectrum of my cantilever appears distorted or has multiple peaks, making spring constant calibration unreliable. What steps should I take? A: A distorted thermal spectrum suggests interference from external vibrations, acoustic noise, or a fluid (if imaging in liquid). Ensure the AFM is on an active or passive vibration isolation table. Check that the instrument cover is properly sealed to minimize air currents. For measurements in air, allow the system to settle for at least 30-60 minutes after handling. Ensure the cantilever holder is securely fastened and that no debris is present. Use a longer measurement time for the thermal tune to improve the signal-to-noise ratio.

Q4: When attempting to determine the contact point for nanoindentation, the force curve shows a significant nonlinear region before the expected contact. What does this mean? A: A pre-contact nonlinear region is typically due to long-range forces such as electrostatic attraction, capillary forces from a water layer, or molecular interaction forces. For nanoindentation research, this obscures the true mechanical contact point. To mitigate this, ensure the sample and cantilever are in a controlled environment (e.g., vacuum or dry nitrogen glovebox). Consider performing chemical plasma cleaning of both the tip and sample to remove contaminants. Using a stiffer cantilever (e.g., > 10 N/m) can also reduce the influence of these adhesive forces.

Q5: The calibrated spring constant from the thermal method differs significantly from the manufacturer's specified value. Which should I trust? A: Always trust the in-situ calibrated value. Manufacturer values are typical averages from a batch and can vary by ±10-50%. The thermal noise method accounts for your specific cantilever mounting, laser alignment, and detector sensitivity. For critical nanoindentation modulus calculations, the spring constant must be measured for the exact cantilever used in the experiment. Document both values, but use the thermally calibrated constant for all data analysis.

Table 1: Typical Parameters for AFM Component Calibration

| Component | Parameter | Target Value/Range | Purpose in Contact Point Determination |

|---|---|---|---|

| Laser & Photodetector | Sum Signal (V) | 3.0 - 6.0 | Ensures sufficient signal-to-noise for deflection measurement. |

| Photodetector | InvOLS (nm/V) | 20 - 100 (varies by lever) | Converts voltage to cantilever deflection. Critical for force calculation. |

| Cantilever | Spring Constant, k (N/m) | 0.1 - 100 (sample-dependent) | Converts deflection to force (Hooke's Law: F = k * d). |

| Thermal Tune | Fit Confidence (R²) | > 0.95 | Indicates reliability of spring constant calibration. |

| Approach | Setpoint Force (nN) | 1 - 5 (for calibration) | Minimizes sample deformation during InvOLS calibration. |

| Environment | Relative Humidity (%) | < 10 (ideal for dry contact) | Reduces capillary forces that obscure the true contact point. |

Table 2: Troubleshooting Quick Reference

| Symptom | Most Likely Cause | Immediate Action |

|---|---|---|

| Drifting InvOLS value | Laser power/alignment drift, thermal drift | Re-center laser, allow system to equilibrate, check for drafts. |

| Noisy/Unstable deflection | Poor laser alignment, vibrations, contamination | Maximize sum signal, check isolation, clean tip and sample. |

| Force curve "jump-to-contact" | High adhesive forces, lever too soft | Increase cantilever stiffness, perform in drier environment. |

| Asymmetric photodetector response | Misaligned laser spot on quadrant | Adjust alignment for zero difference at zero deflection. |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: In-situ Photodetector Sensitivity (InvOLS) Calibration via Thermal Tune

- Mounting: Secure the cantilever in its holder and mount it in the AFM head. Ensure no obstacles are in the approach path.

- Laser Alignment: Align the laser spot to the end of the cantilever and center the reflected beam on the quadrant photodetector. Adjust for maximum sum voltage.

- Approach: Approach the tip to a clean, rigid, and flat sample surface (e.g., sapphire).

- Engage: Engage the servo system with a very low setpoint (~0.5 V) to establish gentle contact.

- Thermal Data Acquisition: With the tip in contact, disable the feedback loop. Record the thermal fluctuations of the deflection signal (in volts) for at least 5 seconds at a sampling rate ≥ 50 kHz.

- Analysis: Fit the power spectral density of the voltage signal to a simple harmonic oscillator model. The equipartition theorem gives InvOLS = √(kB * T / (k * PSD0)), where PSD_0 is the magnitude of the thermal noise peak. Most AFM software automates this calculation.

- Verification: Retract the tip and perform a force curve on the same rigid surface. The slope in contact should be linear, and the calculated deflection (InvOLS * Voltage) should match the Z-piezo movement.

Protocol 2: Determination of Nanomechanical Contact Point

- Calibrate: Complete Protocol 1 to obtain a calibrated InvOLS and spring constant (k).

- Approach Curve: On the sample of interest, perform a slow force-distance curve with a low trigger force (e.g., 1 nN) and a low approach/retract speed (e.g., 100 nm/s).

- Data Collection: Record the raw photodetector deflection voltage (V_d) and Z-piezo displacement (Z) data.

- Convert: Convert Vd to true deflection (d) using: d = InvOLS * Vd.

- Calculate Tip-Sample Separation: Calculate the separation as: Separation = Z - d.

- Identify Contact Point: Plot Force (F = k * d) vs. Separation. The contact point is defined as (a) the point of last stability before a 'jump-to-contact' OR (b) the point where the force curve definitively deviates from the baseline in the absence of a jump. This is often identified as the zero separation point.

- Offset Correction: Subtract the contact point deflection and Z values from the entire dataset to align the contact point to (0,0). All subsequent nanoindentation analysis (e.g., modulus fitting) uses this corrected data.

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions & Materials

| Item | Function in AFM Nanoindentation Setup |

|---|---|

| Standard Calibration Sample (Sapphire Disk) | Provides an atomically smooth, rigid surface for accurate InvOLS and spring constant calibration. |

| Cleaved Mica Substrate | Provides an atomically flat, clean surface for calibration and for preparing thin film samples. |

| Colloidal Probe Cantilevers | Cantilevers with a glued spherical tip (e.g., silica bead) for well-defined Hertzian contact mechanics on soft materials like cells or hydrogels. |

| Diamond-Coated AFM Tips | Ultra-hard tips for indenting very stiff materials (e.g., bone, composites) without tip wear. |

| Plasma Cleaner | Used to remove organic contamination from tips and samples, minimizing adhesive forces for clearer contact point identification. |

| Vibration Isolation Platform | Active or passive isolation system critical for reducing environmental noise, enabling accurate thermal tuning and high-resolution force measurements. |

| Environmental Control Chamber | Encloses the AFM to control temperature and purge with dry gas (N2/Ar), eliminating capillary water layers for precise force spectroscopy in air. |

Visualizations

Diagram 1: AFM Contact Point Determination Workflow

Diagram 2: Laser & Photodetector Alignment Logic

Technical Support Center

Troubleshooting Guides & FAQs

Q1: During visual inspection of my force-distance curve, I cannot consistently identify the exact point where the probe contacts the surface. The transition region appears too gradual. What could be the cause and solution?

A: A gradual transition, often called a "pre-contact" region, is typically due to contaminants or a fluid layer (e.g., water meniscus in ambient air) causing attraction before hard mechanical contact.

- Protocol: First, ensure proper sample and probe cleaning. For experiments in liquid, allow sufficient thermal equilibration (≥30 mins). If the issue persists, use the Tangent Method algorithmically: fit a linear regression to the non-contact (baseline) and contact (sloped) regions. The contact point is the intersection of these two tangents. Software like NanoScope Analysis or Gwyddion have built-in tools for this.

- Prevention: Always perform experiments in a controlled environment (temperature, humidity). Use sharper, cleaner probes.

Q2: When applying the Tangent Method programmatically, small changes in the selected fitting regions lead to large variations in the calculated contact point. How can I improve robustness?

A: This indicates sensitivity to noise or an ill-defined linear region.

- Protocol: Implement a systematic, repeatable region selection criteria. For the non-contact baseline, select the flattest 10-20% of the retract curve before the snap-back. For the contact line, select a region 40-70% into the indentation segment, avoiding the initial non-linear compliance and the plastic deformation zone. Use Table 1 for guidance.

- Solution: Apply a Savitzky-Golay filter (e.g., 2nd order, 5-11 point window) to smooth the data before fitting. Automate the fitting region selection based on the derivative (slope) threshold.

Q3: How do I validate that my chosen contact point determination method (Visual vs. Tangent) is accurate for my nanoindentation modulus calculation?

A: Conduct a self-consistency check using a standard sample with known modulus.

- Protocol:

- Acquire force curves on a known reference material (e.g., fused silica, modulus ~72 GPa).

- Determine contact points for 50+ curves using both Visual Inspection and the Tangent Method.

- Calculate the reduced modulus (Er) for each curve using the Hertz model.

- Compare the mean, standard deviation, and coefficient of variation for Er from both methods. The method yielding an average closest to the known value with the lowest scatter is more accurate for your system.

- Data Presentation: See Table 2 for a hypothetical validation result.

Q4: My force curves in biological media (e.g., on cells or protein layers) show multiple discontinuities or "jumps." Which point should be considered the contact point for nanoindentation?

A: In soft, layered samples, the first significant repulsive inflection point after the jump-into-contact is generally considered the initial contact with the outermost deformable layer. Do not use a jump during the indentation (which may indicate piercing a membrane or structure) as the primary contact point for modulus calculation of the entire layer.

- Protocol: Visually identify the first slope change after the adhesive jump-to-contact. Apply the Tangent Method to the region immediately after this event and a stable portion of the pre-approach baseline. This provides a reproducible, if operationally defined, contact point for comparative measurements.

Data Presentation

Table 1: Tangent Method Fitting Region Selection Guidelines

| Curve Region | Recommended Data Portion | Purpose | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Non-Contact Baseline | Final 10-20% of approach before deflection increase. | Defines zero-force baseline slope. | Must be visually flat; exclude piezo creep at start. |

| Contact Slope | Between 40% and 70% of indentation depth. | Defines sample stiffness (slope). | Avoid initial non-linearity and plastic yielding zone. |

Table 2: Validation Results for Contact Point Methods on Fused Silica

| Determination Method | Calculated Reduced Modulus, Er (Mean ± SD) [GPa] | Coefficient of Variation [%] | Error vs. Known Value (~72 GPa) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Visual Inspection | 68.5 ± 8.2 | 12.0 | -4.9% |

| Algorithmic Tangent | 71.8 ± 3.1 | 4.3 | -0.3% |

| Note: Hypothetical data illustrating typical outcomes. |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol: Systematic Contact Point Determination Using the Tangent Method

- Data Acquisition: Collect a force-distance curve with a sufficiently long non-contact segment (e.g., 100 nm) and a controlled approach speed (e.g., 500 nm/s).

- Data Preprocessing: Convert raw Volts vs. Z-sensor data to Force vs. Piezo displacement. Apply mild smoothing (Savitzky-Golay filter) if noise-to-signal ratio is high.

- Region Selection (Automated):

- Calculate the first derivative (slope) of the force curve.

- Define the baseline region as all points where the absolute slope is < 0.1 pN/nm.

- Define the start of the contact region at the point where the slope exceeds a threshold (e.g., 5x the std. dev. of the baseline slope).

- Define the end of the contact region for fitting at a point 50 nm after the start of contact (or before any significant discontinuity).

- Linear Fitting: Perform a least-squares linear fit to the data in the selected baseline and contact regions.

- Calculate Intersection: Compute the intersection point (piezo displacement, force) of the two linear fits. This coordinate is the operational contact point.

- Validation: Visually overlay the calculated tangents and contact point on the original curve for a subset of data to ensure algorithm correctness.

Mandatory Visualization

Diagram Title: Workflow for Algorithmic Tangent Method

Diagram Title: Visual vs. Tangent Method Comparison

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Materials for Reliable Force-Distance Curve Acquisition

| Item | Function & Importance |

|---|---|

| Standard Calibration Grid (e.g., TGZ1) | Provides known pitch and height for scanner calibration in X, Y, and Z axes. Critical for accurate indentation depth measurement. |

| Reference Sample (Fused Silica or PS/PEO) | A material with known, uniform mechanical properties. Essential for validating the entire contact point and modulus calculation pipeline. |

| Sharp AFM Probes (e.g., RTESPA-300) | Probes with well-defined tip geometry (radius, shape). Necessary for applying correct contact mechanics models (Hertz, Sneddon). |

| Liquid Cell & Buffer Solutions | Enables biologically relevant measurements. Buffer choice (ionic strength, pH) affects electrostatic interactions and sample stability. |

| Vibration Isolation System | An active or passive isolation table minimizes noise floor, leading to cleaner baselines and more precise contact point detection. |

| Software with Batch Processing (e.g., JPKSPM, Igor Pro) | Allows automated, consistent application of the Tangent Method across hundreds of curves, removing user bias and enabling statistics. |

Technical Support & Troubleshooting Center

FAQs & Troubleshooting Guides

Q1: During automated contact point detection using the Linear Fit method, my algorithm consistently identifies the contact point too late (i.e., after the tip has already indented the sample). What could be the cause and how can I fix it? A: This is often caused by an incorrectly defined "pre-contact" or "baseline" region for the linear fit.

- Cause: The selected linear region includes data points that are already influenced by sample contact, causing the fitted line to have a shallower slope. The intersection with the subsequent slope then occurs later.

- Solution: Implement an iterative or rolling linear fit. Dynamically adjust the start and end points of the baseline fit region, selecting the range that yields the highest coefficient of determination (R²) for linearity. This ensures you are fitting the truest non-contact region.

- Protocol: 1. From the raw force-distance curve, define a starting window (e.g., the first 15% of data points). 2. Perform a linear fit and calculate R². 3. Roll the window forward by a small step (e.g., 1% of data points). 4. Repeat until R² drops below a threshold (e.g., 0.995). 5. Use the window with the highest R² for your final baseline fit.

Q2: When using the Slope Threshold method, how do I objectively determine the correct threshold value for my specific experiment, rather than relying on visual guesswork? A: The optimal threshold can be derived statistically from the noise characteristics of your baseline.

- Cause: An arbitrary threshold (e.g., 3x the baseline slope) may be too sensitive for noisy data or too insensitive for very stiff samples.

- Solution: Calculate the threshold based on the standard deviation of the baseline slope.

- Protocol: 1. Calculate the first derivative (slope) for all points in the pre-contact baseline region identified in Q1. 2. Compute the mean (μ) and standard deviation (σ) of these baseline slopes. 3. Set the contact detection threshold to μ + k*σ, where

kis a multiplier. Start with k=5-10 and validate against a manually curated set of curves. 4. For heterogeneous samples, consider calculating this for each curve individually to account for drift.

Q3: My Machine Learning (ML) model for contact point detection performs well on training data but fails on new experimental batches. What steps should I take to improve generalization? A: This indicates overfitting or dataset shift. The model has learned patterns specific to your training set that are not fundamental to the contact detection task.

- Cause: Insufficient diversity in training data (e.g., only one sample type, one cantilever spring constant, or one loading rate).

- Solution: Apply data augmentation and feature engineering focused on invariant properties.

- Protocol: 1. Augment Training Data: To your raw force-distance curves, add simulated offsets (vertical/horizontal shift), inject Gaussian noise proportional to your system's noise floor, and apply mild stretching/compression to the distance axis. 2. Engineer Robust Features: Instead of using raw data points, use features like the normalized slope (slope divided by cantilever stiffness), the variance over a moving window, or the wavelet coefficients of the curve. These are more invariant to absolute force scales. 3. Validate Rigorously: Use leave-one-batch-out cross-validation, where all curves from one entire experimental session are held out as the test set.

Q4: How do I validate and compare the performance of different automated detection algorithms for my research? A: Establish a quantitative benchmark using a manually curated "ground truth" dataset.

- Protocol: 1. Randomly select a representative subset of your force-distance curves (e.g., 200-500). 2. Have 2-3 experienced researchers independently mark the contact point for each curve. Define the contact point as the first unambiguous deviation from the linear baseline. 3. Calculate the inter-operator standard deviation for each curve. Discard curves where disagreement is too high. 4. For each algorithm, calculate the mean absolute error (MAE) and standard deviation against the human consensus for each curve. Present results in a table (see below).

Performance Comparison of Detection Algorithms

Table 1: Quantitative comparison of algorithmic performance against a human-curated ground truth dataset (n=250 AFM force curves).

| Algorithm | Mean Absolute Error (nm) | Error Std Dev (nm) | Processing Speed (curves/sec) | Key Parameter |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Linear Fit Intersection | 1.8 | 2.1 | 9500 | Baseline Region (10-30%) |

| Adaptive Slope Threshold (k=8) | 0.9 | 1.5 | 4200 | Threshold Multiplier (k) |

| Random Forest Classifier | 0.5 | 0.7 | 800 | # of Trees (100) |

| 1D Convolutional Neural Net | 0.4 | 0.6 | 120* | Kernel Size (5) |

Note: Inference speed on GPU. MAE values are for simulated data with a known contact point and added noise.

Experimental Protocol: Benchmarking Contact Point Algorithms

Objective: To quantitatively evaluate and compare the accuracy and robustness of Linear Fit (LF), Slope Threshold (ST), and a supervised Machine Learning (ML) model for AFM nanoindentation contact point determination.

Materials: See "Research Reagent Solutions" below. Method:

- Data Acquisition: Acquire force-distance curves (F-d) on a calibrated AFM using a standard silica sample and a borosilicate sphere probe.

- Ground Truth Creation: Export raw F-d data. Using custom software, have three expert analysts manually label the contact point index for 300 randomly selected curves.

- Algorithm Implementation:

- LF: For each curve, fit a line to the first 20% of data points. Fit a second line to the region where the slope exceeds 50% of the maximum slope. Define contact as the intersection.

- ST: Calculate the numerical derivative. Define contact as the first point where the slope exceeds 8 standard deviations above the mean baseline slope (calculated from the first 15% of data).

- ML: Train a Random Forest model on 200 curves (with held-out ground truth). Use features including moving average, moving standard deviation, and wavelet coefficients from the first 50% of each F-d curve.

- Validation: Apply all three algorithms to the remaining 100 curves. Compute the difference (in data points and nanometers) between each algorithm's output and the consensus human label for each curve.

- Analysis: Calculate the Mean Absolute Error (MAE), Root Mean Square Error (RMSE), and standard deviation for each method. Perform a paired t-test to determine if differences in accuracy are statistically significant (p < 0.05).

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential materials and reagents for AFM nanoindentation contact point research.

| Item | Function/Description | Example/Specification |

|---|---|---|

| Calibrated AFM Probe | Indenter for applying force and measuring sample response. Stiffness must be pre-calibrated. | Bruker RTESPA-300 (k ≈ 40 N/m), MLCT-Bio-DC (k ≈ 0.03 N/m) |

| Reference Sample | A sample with known, elastic, and homogeneous properties for method validation and system calibration. | Fused Silica wafer, PDMS (Sylgard 184, 10:1 ratio), Gold film (100nm thick on mica) |

| Soft Biological Sample | The target sample for drug development research, often viscoelastic and heterogeneous. | Live cell monolayer, reconstituted collagen gel, lipid bilayer. |

| PBS Buffer (1X) | Standard physiological buffer for maintaining biological sample viability and hydration during experiments. | Phosphate Buffered Saline, pH 7.4, sterile filtered. |

| Probe Cleaning Solution | To remove organic contaminants from the probe before and after experiments, ensuring consistent interaction. | Hellmanex III (2%), UV-Ozone cleaner, Oxygen Plasma. |

| Data Acquisition Software | Controls the AFM and records raw cantilever deflection and piezo displacement data. | Bruker Nanoscope Software, Asylum Research IGOR Pro, JPK SPM Control. |

| Analysis Software Suite | Environment for implementing custom detection algorithms and statistical analysis. | Python (NumPy, SciPy, scikit-learn), MATLAB, OriginLab. |

Workflow Diagram: Algorithm Validation Protocol

Algorithm Decision Logic for Contact Point Detection

Technical Support Center: Troubleshooting & FAQs

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: During AFM nanoindentation on live cells, my force curves show excessive noise and drift. What could be the cause? A: This is commonly caused by thermal instability, poor mechanical isolation, or contamination of the cantilever/cell substrate. Ensure the AFM and sample stage are thermally equilibrated (minimum 30 minutes). Use a high-quality anti-vibration table. Check that the liquid cell O-rings are not leaking. Contaminants can be mitigated by rigorous cleaning of substrates and using fresh, filtered culture media or buffer.

Q2: How do I accurately determine the contact point on a very soft hydrogel where the approach curve is non-linear from the start? A: For extremely soft materials (>1 kPa), the classical linear fit method fails. Use an extended nonlinear fitting model (e.g., Hertz, Sneddon) from the initial detectable deflection. Employ a "two-step" contact point determination protocol: First, identify the region where force exceeds baseline noise by 3 standard deviations. Second, iteratively fit the contact mechanics model from this region backward until the fit error minimizes. This point is your effective contact.

Q3: My measured tissue sample stiffness varies dramatically between locations. Is this biological variation or an artifact? A: It is likely real biological heterogeneity, but artifacts must be ruled out. First, ensure the tissue remains fully hydrated and is firmly adhered to the substrate (use a petri dish with a covalently bound adhesive like poly-L-lysine or a Cell-Tak coating). Second, confirm consistent loading rate and indentation depth across measurements. Third, perform a control measurement on a uniform PDMS gel to verify instrument consistency. Map a larger area (>50x50 µm²) to statistically distinguish anatomical structure from artifact.

Q4: When indenting a cell body, I sometimes observe a "lip" or "wrap" event in the force curve before the main contact. What is this and how should I handle it? A: This is a common artifact where the cantilever tip contacts the peripheral actin cortex or membrane protrusions before engaging the main cell body. To mitigate, use a sharper tip (e.g., silicon nitride, 10-20 nm radius) and a slower approach velocity (<1 µm/s). In data analysis, discard curves with this feature, as the true contact point for the soma is ambiguous. Focus measurements on the perinuclear region.

Q5: How often should I calibrate my cantilever's spring constant and sensitivity when working in liquid? A: Calibrate the optical lever sensitivity (InvOLS) in situ for every new liquid environment, cantilever, or temperature change. The spring constant should be calibrated (via thermal tune or Sader method) in air before the experiment. If you must change liquids during a session, re-check the InvOLS in the new liquid, as the refractive index change alters the laser path.

Troubleshooting Guide

| Problem | Possible Cause | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| No Reproducible Force Curves | Sample drifting, loose sample, or piezo creep. | Increase wait time after approach for thermal equilibration (>5 min). Use a stronger adhesive for sample mounting. Apply a piezo creep correction protocol in software. |

| Adhesion "Pull-off" Events Obscuring Retract Curve | Tip or sample is too sticky (hydrophobic or protein-coated). | Use hydrophilic, PEG-coated tips to minimize non-specific adhesion. Increase retract velocity. Add a surfactant (e.g., 0.1% Pluronic F-127) to the buffer. |

| Apparent Stiffness Increasing Over Time | Sample dehydration or consolidation. | Verify liquid cell seals and immersion. For hydrogels, allow full swelling equilibrium (≥1 hour). For tissues, use a perfusion system if imaging >20 minutes. |

| Cantilever Oscillation ("Ring") During Approach | Low damping in liquid, high approach speed. | Reduce approach speed to ≤0.5 µm/s. Use cantilevers with a lower resonant frequency in liquid (<10 kHz) or enable "soft engage" modes if available. |

| Inconsistent Contact Point Algorithm | Incorrect baseline or trigger force setting. | Re-define the baseline from a section of the curve far from contact. Set the trigger force relative to the noise floor (typically 2-3x the RMS noise). Use a consistent, automated algorithm (see protocol below). |

Key Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Standardized Contact Point Determination for Nanoindentation

This protocol frames the contact point determination within the broader thesis context, establishing a reproducible baseline for comparing cells, hydrogels, and tissues.

Objective: To determine the initial point of mechanical contact between an AFM tip and a soft, hydrated sample with minimal ambiguity.

Materials: As per "Scientist's Toolkit" below.

Method:

- Pre-Engagement:

- Approach the tip to ~100 µm above the sample surface in liquid.

- Acquire a thermal noise spectrum of the cantilever to confirm proper damping and spring constant.

Baseline Acquisition:

- Record a 5-second force-distance curve with a 0 nm extension to define the baseline deflection and its standard deviation (σ).

Approach Curve Acquisition:

- Set approach/retract velocity to 1 µm/s.

- Set trigger threshold to 2.5 × σ of the baseline deflection.

- Set maximum indentation force to 0.5-2 nN (sample-dependent).

- Acquire approach curve.

Contact Point Analysis (Algorithm):

- Step A (Noise Floor): Smooth raw deflection data (Savitzky-Golay filter, window 5-11 points).

- Step B (Deviation Detection): Calculate the running standard deviation of deflection over a short window. Define the "detection point" where it exceeds 3σ of the baseline.

- Step C (Model Fitting): From the detection point, fit the subsequent 50-100 nm of tip-sample separation data with the relevant contact model (Hertz/Sneddon). Iteratively shift the fitted region backward until the R² value of the fit is maximized.

- Step D (Validation): The contact point is the tip-sample separation value at the start of the optimal fitted region. Visually inspect 10% of curves to confirm.

Post-Processing: Apply this algorithm uniformly to all curves within an experiment.

Protocol 2: Sample Preparation for Liquid AFM of Soft Tissues

Objective: To prepare a thin, mechanically stable, and hydrated tissue section for reproducible nanoindentation mapping.

Method:

- Fresh tissue is embedded in optimal cutting temperature (OCT) compound and rapidly frozen.

- Cryosection to 10-30 µm thickness onto a sterile, poly-L-lysine-coated glass-bottom Petri dish.

- Thaw sections at room temperature for 2 minutes, then immediately flood with appropriate physiological buffer (e.g., PBS or HEPES).

- Incubate for 1 hour at 4°C to allow tissue adhesion and rehydration.

- Gently rinse with fresh buffer to remove any detached debris prior to AFM mounting.

Table 1: Typical AFM Parameters for Soft Samples in Liquid

| Sample Type | Recommended Cantilever Spring Constant | Tip Geometry | Approach Velocity | Trigger Force | Optimal Indentation Depth | Typical Young's Modulus Range |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adherent Cells | 0.01 - 0.06 N/m | Spherical (2.5-5 µm) | 1-2 µm/s | 50-100 pN | 500-1000 nm | 0.5 - 20 kPa |

| Hydrogels | 0.1 - 0.5 N/m | Spherical (5-20 µm) or Conical | 2-5 µm/s | 0.5-1 nN | 10% of gel height | 0.1 - 100 kPa |

| Soft Tissues (section) | 0.06 - 0.2 N/m | Spherical (5-10 µm) | 0.5-1 µm/s | 0.2-0.5 nN | 1000-2000 nm | 1 - 50 kPa |

| Biopolymers (fibrils) | 0.01 - 0.03 N/m | Sharpened Tips (MLCT) | 0.5-1 µm/s | 50 pN | 5-10 nm | 0.1 - 5 GPa |

Table 2: Common Contact Mechanics Models for Data Fitting

| Model | Sample Type Assumption | Key Formula (Simplified) | Critical Parameter |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hertz (Spherical) | Isotropic, linear elastic, infinite half-space. | ( F = \frac{4}{3} \frac{E}{1-\nu^2} \sqrt{R} \delta^{3/2} ) | Tip Radius (R) |

| Sneddon (Conical/Pyramidal) | Isotropic, linear elastic, infinite half-space. | ( F = \frac{2}{\pi} \frac{E}{1-\nu^2} \tan(\alpha) \delta^{2} ) | Half-opening angle (α) |

| Oliver-Pharr | Elastic-plastic, for stiff materials. | ( S = \frac{2}{\sqrt{\pi}} E_{eff} \sqrt{A} ) | Contact Stiffness (S) |

| Johnson-Kendall-Roberts (JKR) | Highly adhesive soft contact. | Complex, includes work of adhesion (γ). | Surface Energy (γ) |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

| Item | Function/Application |

|---|---|

| Poly-L-Lysine Coated Dishes | Provides a positively charged surface for strong adhesion of cells, tissue sections, or some hydrogels. |

| Cell-Tak | A biological adhesive from mussels used for immobilizing cells and tissues without chemical cross-linking. |

| Pluronic F-127 | Non-ionic surfactant added to buffers (0.01-0.1%) to minimize non-specific adhesion of the tip to the sample. |

| PEGylated AFM Tips | Tips coated with polyethylene glycol to create a non-adhesive, bio-inert surface, crucial for clean force measurements. |

| Silicon Nitride Cantilevers (MLCT) | Bio-compatible, low-reflectivity cantilevers with soft spring constants, ideal for force spectroscopy in liquid. |

| Colloidal Probe Tips | Beads (2-45 µm) glued to cantilevers for well-defined spherical geometry and reduced sample damage. |

| Temperature-Controlled Liquid Cell | Maintains sample at physiological temperature (37°C) during long experiments to ensure viability and consistent mechanics. |

| OCT Compound | Embedding medium for freezing and cryosectioning tissue samples to preserve native structure for AFM. |

Visualizations

AFM Contact Point Determination Algorithm

Liquid AFM Setup for Soft Samples

Technical Support Center

Troubleshooting Guides & FAQs

Q1: My force curves show inconsistent contact points, especially when I change the loading rate. What is the primary cause? A: Inconsistent contact point determination at different loading rates is primarily caused by hydrodynamic drag forces on the cantilever in fluid, or system thermal drift. At high approach velocities, the fluid exerts a significant force on the cantilever, bending it before tip-sample contact, which is misinterpreted as early contact. Protocol: To diagnose, perform force spectroscopy in air on a rigid sample (e.g., silicon) at varying rates (0.1 µm/s to 100 µm/s). Plot the apparent "contact point" deflection vs. log(rate). A linear shift indicates viscous drag. Solution: Implement an active drift compensation system or use the "pre-approach" method: approach at high speed to a set distance (e.g., 100 nm), pause for 5 seconds to allow stabilization, then complete the approach at a very low speed (<0.5 µm/s) for the final contact.

Q2: How do I isolate the true mechanical response from thermal noise in my nanoindentation data on soft polymer gels? A: Thermal noise limits force resolution and obscures the initial contact region. Protocol: 1) Record the cantilever's deflection thermal spectrum (power spectral density) when freely suspended in the medium. 2) Fit the data to a simple harmonic oscillator model to determine the spring constant (k) and the quality factor (Q). 3) During data acquisition, apply a low-pass filter with a cutoff frequency set to at least 10x your indentation rate (e.g., for a 1 Hz indent, filter at 10 Hz). This reduces high-frequency noise without distorting the mechanical response. Solution: Use a cantilever with a lower spring constant (e.g., 0.01-0.1 N/m) to improve signal-to-noise ratio for soft samples.

Q3: My indentation modulus varies significantly with ambient humidity. What environmental controls are necessary for reproducible nanoindentation? A: Humidity affects surface adhesion (capillary forces), sample hydration (for hydrogels), and can cause condensation. For reproducible AFM nanoindentation, control temperature and humidity within a sealed environmental chamber. Protocol: 1) Enclose the AFM head and sample in an environmental hood. 2) Use a dry nitrogen or argon purge for at least 30 minutes prior to and during experiments to maintain relative humidity below 10%. 3) Stabilize the sample temperature using a stage cooler/heater to ±0.5°C of the target for at least 1 hour before measurement. Record both temperature and humidity for all datasets.

Data Tables

Table 1: Recommended Acquisition Parameters for AFM Nanoindentation

| Sample Type | Cantilever Spring Constant (k) | Approach Velocity (v) | Trigger Threshold (Force Setpoint) | Dwell Time at Max Load | Data Sampling Rate |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rigid Materials (Si, Metals) | 10 - 50 N/m | 0.5 - 2 µm/s | 500 nN | 0 ms | 2 kHz |

| Hard Polymers / Bone | 1 - 5 N/m | 0.5 - 1 µm/s | 100 - 200 nN | 50 ms | 5 kHz |

| Soft Polymers & Cells | 0.01 - 0.1 N/m | 0.1 - 0.5 µm/s | 1 - 5 nN | 100 - 500 ms | 10 - 20 kHz |

| Hydrogels & Biomaterials | 0.05 - 0.5 N/m | 0.1 - 0.3 µm/s | 2 - 10 nN | 1000 ms | 10 kHz |

Table 2: Impact of Environmental Factors on Measured Modulus

| Environmental Factor | Typical Variation | Effect on Apparent Elastic Modulus | Control Guideline |

|---|---|---|---|

| Temperature | ±5°C | Can change modulus by 5-20% for polymers | Stabilize to ±0.5°C |

| Relative Humidity | 20% to 80% | Can alter modulus by up to 50% via adhesion/plasticization | Control to ±5% or use dry purge |

| Fluid Medium | Air vs. Liquid | Major change due to buoyancy, drag, and sample swelling | Always note medium; calibrate in situ |

| Thermal Drift | >1 nm/s | Causes erroneous depth calculation, >10% error in modulus | Allow 2 hrs thermal equilibration; use drift correction |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol: In-Situ Cantilever Spring Constant Calibration (Thermal Tune Method)

- Setup: Position the cantilever in the measurement medium (air or liquid) above a clean, featureless area of the sample stage.

- Data Acquisition: Record the deflection signal (in volts) for 5 seconds at a sampling rate of 50 kHz without driving the piezo.

- Analysis: Calculate the Power Spectral Density (PSD) of the deflection signal. Fit the fundamental resonance peak to the simple harmonic oscillator model:

PSD(f) = A / ((f₀² - f²)² + (f₀*f / Q)²). - Calculation: The spring constant

kis given byk = k_B * T * Γ / (π * f₀ * Q * A), wherek_Bis Boltzmann's constant,Tis temperature in Kelvin,Γis a calibration constant (~1 for most AFMs),f₀is resonance frequency,Qis quality factor, andAis the area under the PSD curve. - Validation: Repeat 3 times; the standard deviation should be <10%.

Protocol: Contact Point Determination via Tangent Method

- Acquire Raw Curve: Obtain a force-distance curve with a long non-contact region (≥200 nm).

- Select Baseline Region: In the non-contact portion of the approach curve, fit a linear regression to the deflection vs. piezo displacement data. This defines the baseline slope (often zero in air, non-zero in liquid due to drag).

- Identify Contact Region: Visually inspect the curve for the region where deflection begins to increase non-linearly with displacement.

- Fit Contact Line: Apply a linear fit to the first 10-30 nm of this non-linear region (the initial elastic contact).

- Calculate Intersection: The contact point (piezo displacement at contact) is the x-coordinate where the contact line intersects the baseline. Automate this process via script for batch analysis.

Diagrams

Title: AFM Nanoindentation Experimental Workflow

Title: Contact Point Determination via Tangent Intersection Method

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

| Item | Function in AFM Nanoindentation Research |

|---|---|

| Silicon Nitride Probes (DNP/DNB) | Standard, sharp tips for general nanoindentation on soft to moderately hard samples. Biocompatible for cellular work. |

| Diamond-Coated AFM Tips | Essential for indenting very hard materials (metals, ceramics, bone) to prevent tip wear and blunting. |

| Colloidal Probe (SiO₂ Sphere) | A microsphere attached to a cantilever for well-defined contact geometry, enabling absolute modulus measurement via Hertz model. |

| PEGylated Tips | Tips coated with polyethylene glycol to minimize non-specific adhesion when testing biological samples in fluid. |

| Calibration Gratings (TGZ/TGV) | Samples with known pitch and height for verifying piezo scanner calibration in X, Y, and Z directions. |

| Polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS) Slabs | Soft, homogeneous elastomer used as a reference sample to validate force calibration and contact mechanics models. |

| Liquid Cell with O-Ring Seals | Enclosed chamber for controlling fluid medium and atmosphere (e.g., CO₂, humidity) around the sample during measurement. |

| Vibration Isolation Platform | Active or passive system to dampen acoustic and floor vibrations, critical for stable contact point determination. |

Solving the Nanoscale Puzzle: Troubleshooting Common Issues and Optimizing Contact Point Detection

Troubleshooting Guides & FAQs

Q1: My force curve baseline (non-contact region) is excessively noisy. What are the most common sources? A1: A noisy baseline often originates from environmental or instrumental vibration. First, ensure the AFM is on an active or passive vibration isolation table. Check for acoustic noise (e.g., from talking, equipment fans) and mechanical drafts. Internally, a malfunctioning or contaminated photodetector can introduce electronic noise. Verify laser alignment and photodetector sum voltage. Running the system in a quiet hours test can isolate environmental factors.

Q2: I observe irregular, discontinuous jumps in the contact region of the curve. What does this indicate? A2: Discontinuous jumps (slip-stick events) in the contact region typically indicate poor adhesion between the tip and sample, often due to surface contamination. For nanoindentation on soft materials (e.g., cells, polymers), this can also signify viscoelastic relaxation or plastic yield events. Ensure both tip and sample are clean. For biological samples, perform measurements in appropriate liquid buffer to minimize meniscus and capillary forces. Adjust the approach speed; slower speeds can reduce stick-slip on hydrophobic surfaces.

Q3: The retract curve shows severe hysteresis and does not follow the approach path. Is this an artifact? A3: While some hysteresis is expected due to adhesion or material viscoelasticity, severe deviation often has specific causes. The most common is tip-sample adhesion (e.g., a water meniscus in air). Operating in liquid minimizes this. For soft samples, plastic deformation or sample damage during indentation will cause permanent divergence. Reduce maximum load or use a blunter tip. Scanner nonlinearity or creep can also distort curves; perform regular scanner calibration.

Q4: How can I distinguish between real nanomechanical properties and common force curve artifacts? A4: Systematic variation of experimental parameters is key. The table below summarizes tests to isolate artifacts:

Table 1: Protocols to Distinguish Artifacts from Real Properties

| Observed Anomaly | Diagnostic Test | If Artifact: | If Real Property: |

|---|---|---|---|

| Noisy Baseline | Vary approach speed. | Noise pattern independent of speed. | Noise may correlate with speed. |

| Irregular Contact Line | Change tip (radius, chemistry). | Anomaly persists across tips. | Anomaly changes character with tip. |

| Adhesive Pull-off Events | Measure in controlled humidity/liquid. | Adhesion force changes with medium. | Adhesion is consistent/reproducible. |

| Curve Shape Irregularity | Repeat at different sample locations. | Irregularity is random. | Irregularity is location-specific. |

Experimental Protocol: Isolating Vibration Noise

- Setup: Configure AFM for force spectroscopy mode. Use a standard cantilever (e.g., k ~ 0.1 N/m).