Single Crystal vs Nanoparticle Catalysts: A Comprehensive Guide to Mechanisms, Applications, and Performance Optimization

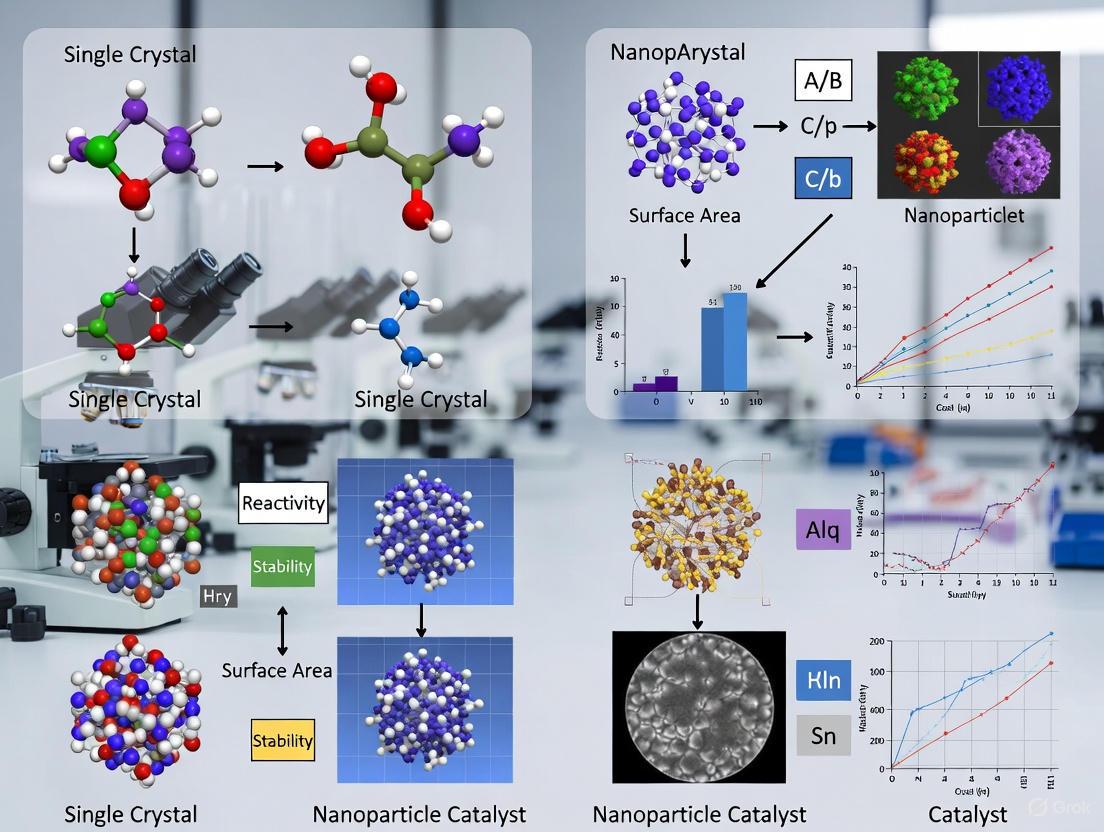

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of single crystal and nanoparticle catalysts, contrasting their fundamental properties, synthesis methodologies, and performance in biomedical and industrial applications.

Single Crystal vs Nanoparticle Catalysts: A Comprehensive Guide to Mechanisms, Applications, and Performance Optimization

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of single crystal and nanoparticle catalysts, contrasting their fundamental properties, synthesis methodologies, and performance in biomedical and industrial applications. It explores the unique catalytic mechanisms arising from well-defined surfaces versus high surface-area nanostructures, including the emerging role of single-atom catalysts. The content delves into practical synthesis and characterization techniques, addresses common challenges in stability and selectivity, and offers a rigorous comparative evaluation of catalytic efficiency, atom utilization, and reactivity. Aimed at researchers and drug development professionals, this review synthesizes cutting-edge innovations to guide the selection and optimization of catalysts for advanced applications, from targeted drug delivery to sustainable chemical synthesis.

Defining the Catalytic Landscape: From Single Crystal Surfaces to Nanoscale Architectures

In the field of catalysis, the precise structural characterization of materials is paramount, as their performance is intrinsically linked to atomic-scale arrangement. For researchers exploring single-crystal versus nanoparticle catalysts, a fundamental challenge lies in accurately distinguishing between materials with crystalline long-range order and those comprising dispersed nanoparticles. This distinction dictates critical properties such as active site availability, stability, and selectivity in catalytic applications ranging from chemical synthesis to drug development [1] [2].

While single crystals offer well-defined, uniform active sites ideal for fundamental studies, nanoparticle dispersions provide high surface-area-to-volume ratios and unique catalytic properties due to their size and shape effects [1]. However, characterizing these systems presents significant technical challenges, as no single technique provides a complete structural picture. This guide objectively compares the capabilities of leading characterization methodologies, supported by experimental data, to enable researchers to select optimal protocols for their specific catalytic systems.

Comparative Analysis of Characterization Techniques

Technical Principles and Capabilities

Different characterization techniques probe distinct aspects of material structure, each with unique strengths and limitations for analyzing crystallinity and dispersion.

Table 1: Core Principles of Key Characterization Techniques

| Technique | Fundamental Principle | Structural Information Obtained | Primary Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Wide-Angle X-ray Scattering (WAXS)/XRD | Measures scattering at wide angles from atomic electrons | Crystalline domain size, crystal structure, phase identification, lattice parameters [3] | Quantifying crystallinity in catalysts, phase composition |

| Small-Angle X-ray Scattering (SAXS) | Examines scattering at small angles (near beam) | Overall nanoparticle size, shape, and size distribution regardless of crystallinity [3] | Size distribution of nanoparticle dispersions, aggregation state |

| Analytical Disc Centrifugation (ADC) | Separates particles by size under centrifugal force | Hydrodynamic size distribution based on sedimentation velocity [4] | High-resolution size analysis of mixed dispersions |

| Scanning Mobility Particle Sizing (SMPS) | Measures electrical mobility diameter of aerosolized particles | Size distribution of aerosolized nanoparticles after nebulization [4] | Characterization of colloidal systems after phase transfer |

| Electron Microscopy (EM) | Direct imaging using electron beams | Direct visualization of particle size, shape, and morphology [4] [3] | Qualitative analysis of nanoparticle morphology and dispersion |

Performance Comparison: Resolution and Accuracy

Experimental studies directly comparing these techniques reveal significant differences in their ability to resolve complex nanoparticle systems.

Table 2: Experimental Performance Comparison for Binary Nanoparticle Mixtures*

| Technique | Able to Resolve 1:1 Mixture of Au (∼20 nm) & Ag (∼70 nm) NPs | Size Resolution | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Dynamic Light Scattering (DLS) | No - unable to resolve bimodal distribution [4] | Low - suitable for monomodal distributions only | Limited resolution for polydisperse systems; assumes spherical particles |

| Analytical Disc Centrifugation (ADC) | Yes - provides quantitative size data [4] | High - excellent size resolution | Requires predefined particle density; limited to dispersions |

| Scanning Mobility Particle Sizing (N+SMPS) | Yes - independent of particle density [4] | High - matches ADC resolution | Requires aerosolization; potential for artifact formation |

| Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM) | Yes - provides semi-quantitative data [4] | Very high - direct visualization | Small sampling area; potential sample preparation artifacts |

| SAXS/WAXS Combination | Yes - provides bulk quantitative data [3] | High for crystallite size (WAXS) & overall size (SAXS) | Complex data analysis; requires specialized expertise |

*Data adapted from comparative studies of metallic nanoparticle dispersions [4]

The combination of SAXS and WAXS is particularly powerful for catalyst characterization, as it simultaneously quantifies both the crystalline domains (via WAXS) and the overall nanoparticle size (via SAXS). This is crucial for understanding catalysts where crystalline cores may be embedded in amorphous shells or supports [3]. The discrepancy between SAXS and WAXS size measurements can reveal the degree of crystallinity within nanoparticles, a critical parameter for catalytic performance.

Experimental Protocols for Comprehensive Characterization

Integrated SAXS/WAXS Methodology for Catalyst Characterization

Protocol Objective: Simultaneously quantify size distribution and degree of crystallinity in nanoparticle catalysts [3].

Materials and Reagents:

- Nanoparticle powder sample (e.g., CeO₂ catalysts)

- Appropriate dispersant solvent (if required for SAXS)

- Standard sample holders for SAXS (capillary/cell) and WAXS (flat plate)

Experimental Workflow:

- Sample Preparation: For dispersible nanoparticles, prepare stable dispersion at appropriate concentration to minimize interparticle interactions. For powdered catalysts, load directly into sample holders.

- SAXS Data Collection: Collect scattering intensity at small angles (typically 0.1-5°). Multiple exposure times may be necessary to ensure adequate signal-to-noise.

- WAXS Data Collection: Collect wide-angle scattering pattern encompassing major diffraction peaks (typically 5-80° 2θ for laboratory instruments).

- Data Analysis - SAXS: Fit intensity curve using appropriate model (e.g., lognormal size distribution) accounting for particle shape, size distribution, and interparticle interactions.

- Data Analysis - WAXS: Perform line-broadening analysis of diffraction peaks or whole-pattern fitting to determine crystalline domain size distribution.

- Comparative Analysis: Calculate the median sizes from the sixth-momentum integral (SAXS) and fourth-momentum integral (WAXS). The discrepancy provides information on crystallinity and size dispersivity.

Critical Considerations: The presence of NP-NP interaction effects can complicate SAXS analysis and must be accounted for in modeling. For WAXS, the choice between individual peak fitting and whole pattern fitting depends on the complexity of the crystal structure and quality of the diffraction data [3].

Figure 1: Integrated SAXS/WAXS characterization workflow for simultaneous analysis of nanoparticle size and crystallinity [3].

Nebulization with SMPS for Dispersion Characterization

Protocol Objective: Characterize colloidal nanoparticle dispersions with high size resolution independent of particle density [4].

Materials and Reagents:

- Nanoparticle dispersion (e.g., Au-PVP ~20 nm, Ag-PVP ~70 nm)

- Newly developed nebulizer (e.g., TSI model 3485 prototype)

- Scanning Mobility Particle Sizer (SMPS)

- Appropriate solvents and standards for calibration

Experimental Workflow:

- Dispersion Preparation: Sonicate nanoparticle dispersion for 5 minutes immediately before analysis to ensure deagglomeration.

- Nebulization: Feed dispersion into nebulizer operating at optimized conditions to produce droplets containing single nanoparticles.

- Drying and Charge Neutralization: Pass aerosol through diffusion dryer and neutralizer to produce dried, charge-equilibrated particles.

- Mobility Sizing: Direct aerosol through SMPS system consisting of Differential Mobility Analyzer (DMA) and particle counter.

- Data Analysis: Convert electrical mobility distribution to particle size distribution using appropriate inversion algorithms.

- Validation: Compare results with ADC or EM data to confirm accuracy.

Critical Considerations: This method minimizes the problem of non-volatile residue formation that plagues traditional aerosol-based characterization methods. The technique is particularly valuable for analyzing complex, polydisperse systems where density-based methods like ADC face limitations [4].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Key Research Reagents and Materials for Nanoparticle Characterization

| Reagent/Material | Function/Application | Example Use Cases | Critical Parameters |

|---|---|---|---|

| Poly(N-vinylpyrrolidone) (PVP) | Stabilizing agent for metallic nanoparticles [4] | Prevents agglomeration of Au, Ag nanoparticles during synthesis and characterization | Molecular weight, concentration, binding affinity |

| Polymer-grafted Nanoparticles | Model systems for studying dispersion behavior [5] | Fundamental studies of nanoparticle assembly and crystallization | Grafting density, polymer molecular weight, compatibility |

| Cerium Oxide (CeO₂) Nanoparticles | Model catalyst for characterization studies [3] | SAXS/WAXS methodology development for crystalline catalysts | Size, morphology, surface functionality |

| Polyolefin Precipitants (PP/PE) | Inducing nanoparticle crystallization for analysis [6] | Controlled assembly of 3D nanoparticle crystals from dilute solutions | Molecular weight (<8 KDa), concentration, solubility |

| Specific Gases (H₂, CO) | Modifying nanoparticle morphology and structure [2] | Reversible structural variation studies in catalytic nanoparticles | Gas purity, pressure, treatment temperature and duration |

Distinguishing between crystalline long-range order and nanoparticle dispersion requires a multifaceted analytical approach, as no single technique provides a complete structural picture. For comprehensive catalyst characterization, the combination of SAXS and WAXS offers distinct advantages in simultaneously quantifying overall nanoparticle size and crystalline domain size [3]. For specialized applications requiring high resolution of complex dispersions, nebulization with SMPS provides exceptional capability independent of particle density [4].

The choice of characterization methodology should be guided by specific research questions regarding the catalyst system. Studies focusing on structure-property relationships in single-crystal catalysts may prioritize WAXS/XRD for precise crystallographic information, while research on nanoparticle dispersions may emphasize SAXS and SMPS for accurate size distribution analysis. As catalytic materials continue to evolve in complexity, including emerging classes like integrative catalytic pairs and single-atom catalysts [1], these fundamental characterization principles will remain essential for advancing both fundamental understanding and practical applications in catalysis research.

In the field of catalysis, the fundamental properties of a material dictate its functionality and efficiency. For researchers and scientists, particularly those developing catalysts for applications ranging from industrial synthesis to drug development, understanding the core physicochemical properties of catalytic materials is paramount. This guide provides a structured comparison between two prominent classes of materials: single crystals, with their long-range, ordered atomic structure, and nanoparticles, characterized by their high surface area and nanoscale dimensions. The performance of these materials is objectively compared based on three critical properties: surface area, quantum effects, and surface plasmon resonance. The discussion is framed within ongoing research investigating whether well-defined single crystal facets or the highly tunable, defect-rich surfaces of nanoparticles offer superior catalytic platforms.

Comparative Analysis of Key Properties

The distinct behaviors of single crystals and nanoparticles arise from fundamental differences in their physical and electronic structures. The table below provides a comparative overview of these key properties.

Table 1: Comparative analysis of key physicochemical properties in single crystals vs. nanoparticles.

| Property | Single Crystals | Nanoparticles |

|---|---|---|

| Surface Area | Low specific surface area; well-defined, atomically flat facets. | Very high specific surface area; large surface-to-volume ratio [7]. |

| Quantum Effects | Absent; bulk electronic structure with continuous energy bands. | Pronounced size-dependent quantum effects due to quantum confinement; discrete energy levels in small nanoclusters [7] [8]. |

| Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR) | Generally absent in bulk form. | Exhibited by noble metal nanoparticles (e.g., Au, Ag, Cu); tunable LSPR based on size, shape, and composition [9] [10]. |

| Primary Catalytic Sites | Ordered terraces and steps of specific crystal facets (e.g., {100}, {111}) [10]. | Corners, edges, and high-index facets; under-coordinated surface atoms [10]. |

| Structural Tunability | Limited to the selection of pre-defined crystal facets. | Highly tunable; size, shape, and composition can be precisely controlled to tailor properties [11] [10]. |

Surface Area and Surface Effects

The surface area of a catalyst directly correlates with the number of available active sites for a reaction.

- Nanoparticles are defined by their high specific surface area and massive surface-to-volume ratio [7]. This means a significant fraction of their atoms is situated on the surface, leading to enhanced chemical reactivity. These surface atoms have fewer direct neighbors than atoms in the bulk, which lowers their binding energy and can significantly affect material properties, such as reducing the melting point [7]. In catalysis, this high surface density of atoms often results in higher activity per unit mass. However, a key challenge is the strong attractive interactions between nanoparticles, which can lead to agglomeration or aggregation, effectively reducing the available surface area and compromising performance [7].

- Single Crystals, in contrast, possess a much lower specific surface area. Their primary advantage lies in their well-defined, atomically flat facets (e.g., {100}, {110}, {111}), which allow for precise mechanistic studies. Researchers can correlate specific reaction pathways and selectivities to particular atomic arrangements on the surface [10]. This makes them invaluable model systems for understanding surface chemistry without the complicating factors of high surface area and heterogeneous sites.

Quantum Confinement and Electronic Effects

When material dimensions shrink to the nanoscale, quantum mechanical effects become dominant.

- Nanoparticles exhibit quantum confinement when their size approaches the exciton Bohr radius of the material [7]. This confinement leads to the discretization of energy levels, profoundly altering their electronic, optical, and magnetic properties. For example, semiconductor nanoparticles (quantum dots) experience a size-tunable bandgap [7] [11]. In metallic systems, this can cause non-magnetic bulk materials like Pd, Pt, and Au to become magnetic at the nanoscale [7]. The catalytic properties are also directly impacted, as quantum confinement modifies electron affinity—the ability to donate or accept electrical charges—which is a cornerstone of catalytic activity [7]. The electronic structure evolves from discrete energy levels in sub-nanometer clusters to semi-discrete bands in quantum-sized small particles (~2 nm, ~10³ atoms) [8].

- Single Crystals display a bulk-like electronic structure with continuous energy bands. They do not exhibit quantum confinement effects, and their electronic properties are intrinsic to the material itself, not tunable by size.

Surface Plasmon Resonance

Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR) is a unique optical phenomenon exhibited by certain nanomaterials.

- Nanoparticles of noble metals (e.g., Au, Ag, Cu) support Localized Surface Plasmon Resonance (LSPR), which is the collective, resonant oscillation of conduction electrons when excited by light [9] [10]. This effect leads to two primary catalytic enhancement mechanisms under illumination:

- Near-field enhancement: The LSPR concentrates electromagnetic fields on the nanoparticle surface, creating highly localized "hot spots" that can enhance reactions [10].

- Hot-carrier generation: The decay of plasmons generates highly energetic (hot) electrons and holes that can be transferred to adsorbates, driving chemical transformations [10]. The LSPR is highly tunable; the resonance wavelength can be controlled by varying the nanoparticle's size, shape, and composition [10]. In catalytic applications, research shows that for plasmonic nanoparticles, the abundance of hot carriers and electric field enhancement at edges and corners can dominate over the traditional crystal facet effect observed in dark conditions [10].

- Single Crystals do not exhibit LSPR in their bulk form. While a crystal's surface can influence plasmonic behavior in nanostructures derived from it, the SPR phenomenon itself is a definitive property of nanostructures, not bulk single crystals.

Experimental Data and Protocols

To illustrate the comparison with experimental data, this section summarizes key findings and methodologies from recent studies on shaped nanoparticles, which bridge the concepts of crystalline facets and nanoscale properties.

Experimental Comparison of Shaped Gold Nanoparticles

Gold nanoparticles with different shapes but similar size and LSPR wavelength provide an excellent model system to decouple facet effects from plasmonic effects.

Table 2: Experimental data on electrocatalytic CO₂ reduction performance of shaped Au nanoparticles [10].

| Nanoparticle Shape (Exposed Facet) | Faradaic Efficiency for CO (Dark) | Faradaic Efficiency for CO (Light) | Key Finding Under Illumination |

|---|---|---|---|

| Rhombic Dodecahedron ({110}) | ~94% (at -0.67 VRHE) | ~94% | No plasmonic enhancement; performance dictated by facet. |

| Nanocube ({100}) | ~69% (at -0.67 VRHE) | Increased | Moderate plasmonic enhancement. |

| Octahedron ({111}) | ~51% (at -0.67 VRHE) | ~100% (Doubled) | Strong plasmonic enhancement; hot carriers dominate over facet. |

Detailed Experimental Protocol

The following workflow details the synthesis and testing of shaped nanoparticles for plasmonic catalysis studies, as referenced in the data above [10].

Diagram 1: Experimental workflow for synthesis and testing of shaped plasmonic nanocatalysts.

Title: Plasmonic Catalyst Synthesis and Testing Workflow

Key Steps in the Protocol:

- Synthesis of Shaped Nanoparticles: Utilizing seed-mediated growth methods in the presence of surfactants like cetyltrimethylammonium bromide (CTAB) to produce monodisperse Au nanocubes (NCs {100}), rhombic dodecahedra (RDs {110}), and octahedra (OCs {111}) [10].

- Physicochemical Characterization:

- Electron Microscopy (SEM/TEM): To confirm uniform shape and size (~60 nm in the referenced study).

- HRTEM and SAED: To verify the single-crystalline nature and identify the d-spacing of the exposed facets.

- X-ray Diffraction (XRD): To confirm the face-centered cubic (FCC) crystal phase.

- UV-Vis-NIR Spectroscopy: To measure the LSPR wavelength and ensure a single, sharp resonance peak for each shape.

- Electrocatalytic Testing: Depositing the nanoparticles on a carbon support to form a working electrode. Performance is evaluated in a CO₂-saturated electrolyte using a standard three-electrode system (e.g., Ag/AgCl reference, Pt counter) [10].

- Plasmonic Activation: Illuminating the electrode with a light source (e.g., laser, LED) tuned to the LSPR wavelength (e.g., ~540 nm for Au NPs) while applying an electrochemical potential.

- Product Analysis: Quantifying gas products (e.g., CO, H₂) using gas chromatography (GC) and liquid products via proton nuclear magnetic resonance (¹H NMR) to calculate Faradaic efficiency and partial current densities.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Key reagents, materials, and equipment for experiments with single crystal and nanoparticle catalysts.

| Item | Function / Description | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| Single Crystal Electrodes | Well-defined, atomically flat surfaces with specific Miller indices (e.g., Pt(111), Au(100)). | Model studies to probe facet-dependent reaction mechanisms without nanoscale effects. |

| Metal Precursor Salts | Source of metal ions for nanoparticle synthesis (e.g., HAuCl₄, AgNO₃). | Reduction to form metallic nanoparticles in solution-phase synthesis. |

| Shape-Directing Surfactants | Molecules that selectively adsorb to specific crystal facets, guiding growth. | CTAB for synthesizing Au nanorods or nanocubes [10]. |

| Electrochemical Workstation | Instrument for applying controlled potentials/currents and measuring electrochemical response. | Conducting electrocatalytic tests (e.g., LSV, chronoamperometry) for CO₂RR or HER. |

| In-situ/Operando Characterization Cells | Specialized reactors allowing analysis of catalysts under working conditions. | Performing in-situ XAS or XRD to monitor electronic and structural changes during reaction [11]. |

| Gas Chromatography (GC) | Analytical instrument for separating and quantifying gas-phase species. | Analyzing products of gas-involving reactions (e.g., CO₂RR, methane oxidation). |

The choice between single crystal and nanoparticle catalysts is not a matter of declaring one universally superior, but rather of matching the material's properties to the application's requirements. Single crystals are the quintessential model system, providing unparalleled fundamental insight into the intrinsic activity of specific crystal facets. In contrast, nanoparticles offer practical advantages through their high surface area and tunable properties, including quantum confinement and surface plasmon resonance, which can be harnessed to achieve activity and selectivity that may not be possible with bulk crystals. Contemporary research, as evidenced by studies on shaped nanoparticles, reveals a complex interplay where nanoscale effects like plasmonic hot-carrier generation can even override the traditional influence of crystal facets. The future of catalyst design lies in the sophisticated engineering of nanoparticles, leveraging the foundational understanding provided by single crystal studies to create next-generation catalytic materials for energy conversion and pharmaceutical development.

Single-atom catalysts (SACs), featuring isolated metal atoms stabilized on solid supports, represent a revolutionary advancement that bridges the gap between homogeneous and heterogeneous catalysis. They combine the high activity and selectivity of molecular homogeneous catalysts with the easy separation and reusability of traditional heterogeneous catalysts [12]. This new class of materials achieves nearly 100% atom utilization efficiency, dramatically altering the electronic properties and catalytic performance compared to nanoparticles (NPs) and clusters [13]. The following sections provide a detailed, data-driven comparison of SACs against nanoparticle catalysts, outline key experimental protocols for their study, and visualize their unique properties and synthesis pathways.

{width="760"}

Performance Comparison: SACs vs. Nanoparticle Catalysts

The table below summarizes key performance metrics for SACs and nanoparticle (NP) catalysts across various reactions, highlighting the distinct advantages and trade-offs of each catalyst type.

| Catalytic Reaction | Catalyst Type | Key Performance Metrics | Remarks on Selectivity/Stability |

|---|---|---|---|

| CO-SCR (NO Reduction) [13] | Ir1/m-WO3 (SAC) | 73% NO conversion, 100% N2 selectivity at 350°C | Superior N2 selectivity under specific conditions |

| Fe1/Al2O3 (SAC) | ~100% NO conversion, ~100% N2 selectivity at 400°C | Excellent activity and selectivity at higher temperatures | |

| Chlorine Evolution (CER) [14] | NiN3O-O (SAC) | 75 mV overpotential, 95.8% selectivity for Cl2 | Performance comparable to noble-metal-based electrodes |

| Propane Dehydrogenation [12] | Pt Single Atom on Cu | High selectivity & stability for >120 h at 520°C | Surpasses Pt nanoparticle catalysts under identical conditions |

| Catalytic Ozonation [15] | CoNC-1000 (Isolated Co-SA) | High OUE & TOF; Long-term stability in real wastewater | Nonradical pathway with high adaptability to complex water matrices |

| CoNC-800 (Co-SA with Co-NPs) | Lower OUE & TOF | Radical pathway with inferior reactivity and ozone utilization |

Experimental Protocols for SAC Synthesis and Characterization

Detailed Synthesis Protocol: ZIF-8-Derived M-N-C SACs

This is a common and scalable method for preparing SACs with metal-nitrogen-carbon (M-N-C) structures [16].

Preparation of Metal-doped ZIF-8 Precursor:

- Function: ZIF-8, a zeolitic imidazolate framework, serves as a porous host to trap and disperse metal atoms.

- Procedure: Dissolve zinc nitrate hexahydrate and a small quantity of the target metal salt (e.g., copper nitrate for Cu-SACs) in methanol. In a separate container, dissolve 2-methylimidazole in methanol.

- Mixing: Rapidly pour the 2-methylimidazole solution into the metal salt solution under vigorous stirring. Continue stirring for several hours at room temperature.

- Aging and Centrifugation: Allow the mixture to age, then recover the resulting crystalline precipitate (e.g., Cu-ZIF-8) by centrifugation. Wash the solid thoroughly with methanol and dry overnight.

High-Temperature Pyrolysis:

- Function: Converts the MOF precursor into a nitrogen-doped carbon support while reducing the metal cations to stable, atomically dispersed sites.

- Procedure: Place the dried precursor in a tube furnace. Pyrolyze under an inert atmosphere (e.g., argon or nitrogen) at a predetermined temperature (typically 800-1000°C) for 1-3 hours [15] [16].

- Critical Control: Temperature is crucial. Higher temperatures (e.g., 1000°C) can vaporize aggregated nanoparticles, yielding purer SACs, but may also reduce metal loading [15].

Acid Washing:

- Function: Removes unstable and aggregated metal nanoparticles, leaving behind the strongly anchored single atoms.

- Procedure: Treat the pyrolyzed material with an acid solution (e.g., sulfuric acid) at an elevated temperature (e.g., 80°C) for several hours. Filter, wash, and dry to obtain the final SAC [15] [16].

{width="760"}

Essential Characterization Techniques

Confirming the atomic dispersion and understanding the electronic structure of SACs requires advanced characterization.

- Aberration-Corrected HAADF-STEM: Directly images isolated heavy metal atoms as bright dots against the darker support [15] [13].

- X-ray Absorption Spectroscopy (XAS):

- Extended X-ray Absorption Fine Structure (EXAFS): Provides chemical evidence for the absence of metal-metal bonds, confirming atomic dispersion. The dominant peak is typically from the metal-nitrogen/oxygen coordination shell [15].

- X-ray Absorption Near Edge Structure (XANES): Reveals the oxidation state and electronic configuration of the metal single atoms [12].

- In Situ/Operando Spectroscopy: Monitors the dynamic changes of the SACs under real reaction conditions, providing insights into the true active sites and reaction mechanisms [12].

The Researcher's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

| Item | Function/Description |

|---|---|

| Zeolitic Imidazolate Framework-8 (ZIF-8) | A metal-organic framework (MOF) used as a sacrificial template and precursor to create a high-surface-area, nitrogen-doped carbon support [16]. |

| Metal Salts (e.g., Cu, Co, Ir) | Source of the catalytic metal atoms. The type and concentration are carefully controlled to prevent aggregation [16]. |

| Polydopamine | An alternative nitrogen-rich polymer precursor that can be used to synthesize SACs, offering flexibility in design [16]. |

| Inert Gas (Ar/N2) | Creates an oxygen-free atmosphere during high-temperature pyrolysis to prevent unwanted oxidation and control the carbonization process [15] [16]. |

Synergistic Systems: Co-existence of Single Atoms and Nanoparticles

A cutting-edge frontier involves designing catalysts where SACs and nanoparticles co-exist to create synergistic effects [17] [18].

- Electronic Modulation: Nanoparticles can electronically perturb nearby single-atom sites, altering their spin state and binding with reactants. This can be beneficial or detrimental, depending on the reaction [15].

- Tandem Catalysis: The nanoparticle and single atom can catalyze different steps in a reaction sequence, improving overall efficiency [17] [18].

- Stabilization: Single atoms can act as anchoring sites for nanoparticles, preventing their agglomeration and enhancing the catalyst's durability [17].

{width="760"}

SACs have firmly established themselves as a distinct and valuable class of catalysts, successfully bridging the homogeneous and heterogeneous worlds. While they demonstrate unparalleled atomic efficiency and selectivity for numerous reactions, their future development hinges on overcoming challenges related to scalable synthesis, long-term stability under harsh industrial conditions, and increasing active site density [19] [13]. The emerging paradigm of hybrid SAC-NP systems offers a promising pathway to engineer catalysts with superior activity, selectivity, and stability by leveraging the unique strengths of both single atoms and nanoparticles [17] [18]. As synthesis and characterization techniques continue to advance, the transition of SACs from an academic curiosity to an industrially relevant technology is steadily progressing [19] [12].

Electronic Structure and Coordination Environments in Nanoparticles vs. Single Sites

In catalytic science, the geometric and electronic structures of active sites dictate catalyst performance, influencing activity, selectivity, and stability. This guide provides a comparative analysis of two dominant catalyst classes: traditional metallic nanoparticles (NPs) and emerging single-atom catalysts (SACs). Framed within broader research on single-crystal versus nanoparticle catalysts, this comparison examines how atomic dispersion fundamentally alters coordination environments and electronic properties. Nanoparticles feature metallic ensembles and surface sites with varied coordination, while SACs comprise isolated metal atoms on supports, offering well-defined, uniform coordination environments. Understanding these distinctions is crucial for rational catalyst design in energy conversion, environmental remediation, and chemical synthesis [1] [13] [20].

Fundamental Structural and Electronic Comparisons

Nanoparticles are nanoscale metal particles, typically ranging from 1 to 100 nanometers, containing tens to thousands of atoms. Their catalytic activity stems from under-coordinated surface atoms and terraces, presenting a distribution of active sites. The electronic structure of nanoparticles is characterized by continuous band structures, where catalytic properties are influenced by collective electronic phenomena such as d-band centers and ensemble effects [13] [21] [20]. Their coordination environments are inherently heterogeneous, including corner, edge, and facet sites with different coordination numbers and geometries, which complicates establishing clear structure-activity relationships [13].

Single-Atom Catalysts (SACs) consist of isolated metal atoms stabilized on solid supports, often through heteroatom coordination (e.g., N, O, S) in materials like nitrogen-doped carbon or metal oxides. This configuration achieves maximum atom utilization efficiency, approaching 100%. SACs possess discrete molecular-like electronic structures, characterized by distinct energy levels rather than continuous bands. This makes their catalytic behavior highly sensitive to the local coordination environment—including the identity, number, and arrangement of coordinating atoms [22] [13] [23]. The well-defined, uniform nature of their active sites allows for precise mechanistic studies and tuning of catalytic properties.

Table 1: Comparative Overview of Nanoparticles and Single-Atom Catalysts.

| Feature | Nanoparticles (NPs) | Single-Atom Catalysts (SACs) |

|---|---|---|

| Active Site | Metallic ensembles, surface sites | Isolated, dispersed metal atoms |

| Atomic Utilization | Low (only surface atoms participate) | High (theoretically ~100%) |

| Coordination Environment | Heterogeneous (varied CNs on corners, edges, facets) | Homogeneous, well-defined (e.g., M-N(_4)) |

| Electronic Structure | Metallic band structure | Molecular-like, discrete energy levels |

| Typical Supports | Metal oxides, carbon, ceramics | N-doped carbon, MOFs, functionalized oxides |

| Structure-Activity Relationship | Complex, based on size/shape | More precise, based on coordination chemistry |

| Key Strengths | Versatility, suitable for multi-step reactions | High selectivity, maximal efficiency, tunability |

Coordination Environment and Engineering Strategies

The local coordination environment of a metal active site is a primary determinant of its catalytic performance, influencing reactant adsorption, activation energy, and intermediate stabilization.

Coordination in Nanoparticles

In nanoparticles, the coordination environment is intrinsically tied to the particle's size and shape. Coordination Number (CN) varies significantly across different surface sites: atoms on terraces have higher CNs (e.g., CN=9 on an fcc(111) facet), while those at edges (lower CN) and corners (lowest CN) are often more active but can also be prone to overly strong binding leading to poisoning or sintering. Engineering strategies focus on morphology control to expose specific crystal facets and the creation of bimetallic alloys or core-shell structures to tailor the electronic structure of surface atoms through ligand and strain effects [21] [20].

Coordination in Single-Atom Catalysts

SACs offer unparalleled precision in coordination engineering. The most common motif is the symmetric M-N(_4) site, analogous to molecular macrocyclic complexes. Recent advances focus on breaking this symmetry to optimize electronic properties [23].

Key Engineering Strategies for SACs:

- Heteroatom Doping: Partial substitution of nitrogen in the M-N(4) plane with atoms of different electronegativity (e.g., S, P, B) creates an asymmetric electronic field. This tunes the d-band center of the metal, enhancing the adsorption and activation of reactants like O(2) for the oxygen reduction reaction (ORR) [22] [23].

- Axial Coordination: Introducing a fifth ligand above or below the M-N(_4) plane further distorts the electronic density. This can break the scaling relations that limit the performance of symmetric sites, particularly in reactions involving multiple intermediates [23].

- Dual-Metal Sites: Creating structures with two adjacent but not-bonded metal atoms (e.g., Ni–Fe, Pt–Fe) enables electronic synergy. The second metal site can modulate the orbital filling of the first, optimizing intermediate binding energies. More complex structures involve directly bonded bimetallic sites or those bridged by non-metal atoms (O, N, S), which can enable cooperative catalysis in multi-step reactions [1] [23].

Table 2: Experimental Data Comparing Catalytic Performance.

| Catalyst | Reaction | Key Performance Metric | Conditions | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ir1/m-WO3 (SAC) | CO-SCR (NO reduction) | 73% NO Conversion, 100% N(_2) Selectivity | 350 °C, GHSV=50,000 h⁻¹ | [13] |

| 0.3Ag/m-WO3 (SAC) | CO-SCR (NO reduction) | ~73% NO Conversion, 100% N(_2) Selectivity | 250 °C, GHSV=50,000 h⁻¹ | [13] |

| Cr0.19Rh0.06CeOz (SAC) | CO-SCR (NO reduction) | 100% NO Conversion, 100% N(_2) Selectivity | 200 °C, GHSV=6,500 h⁻¹ | [13] |

| Fe1/CeO2-Al2O3 (SAC) | CO-SCR (NO reduction) | 100% NO Conversion, 100% N(_2) Selectivity | 250 °C, GHSV=30,000 h⁻¹ | [13] |

| Pt1/FeOx (SAC) | CO Oxidation | Higher Turnover Frequency (TOF) than Au NPs | Not Specified | [13] |

| Conventional Pt NPs | Oxygen Reduction Reaction (ORR) | Baseline Activity | Acidic Media | [22] |

| M-N-C SACs (Heteroatom-doped) | Oxygen Reduction Reaction (ORR) | Reduced overpotential, enhanced 4e⁻ selectivity vs. NPs | Acidic Media | [22] |

Experimental Characterization and Computational Modeling

Key Characterization Techniques

Resolving the structure of catalytic sites requires advanced spectroscopy and microscopy.

- Aberration-Corrected HAADF-STEM: Directly images isolated heavy metal atoms on lighter supports, confirming atomic dispersion [24] [13].

- Synchrotron-Based X-Ray Absorption Spectroscopy (XAS): Provides average information on oxidation state (XANES) and local coordination (EXAFS), including bond lengths and coordination numbers, for both NPs and SACs [24] [23].

- Solid-State NMR Spectroscopy: A powerful technique for characterizing the local environment of suitable nuclei, such as (^{195})Pt. It can distinguish between different coordination geometries (e.g., square-planar Pt(II)) and quantify site homogeneity in SACs, offering molecular-level precision that complements XAS [24].

- In situ/Operando Characterization: Monitoring catalyst structure under reaction conditions (e.g., using operando XAS or NMR) is crucial to identify the true active sites and understand deactivation mechanisms like sintering or poisoning [22] [24].

Computational Modeling

Computational methods, particularly Density Functional Theory (DFT), are indispensable for interpreting experimental data and establishing structure-activity relationships.

- Modeling Nanoparticles: Requires representing a distribution of active sites. Calculations often focus on extended surfaces (as models for facets) and small clusters (as models for corners/edges) to understand size and shape effects. Key challenges include modeling ensemble effects, the dynamic nature of catalysts under reaction conditions, and the influence of the support and solvent [21].

- Modeling SACs: Typically involves a periodic slab or a molecular cluster model with a single metal atom in a defined coordination environment. DFT is highly effective for calculating the adsorption energies of reaction intermediates, proposing mechanisms, and explaining how heteroatom doping or axial coordination tunes electronic structure [22] [23].

- Emerging Tools: Machine Learning (ML) is being integrated into nanocatalysis research to navigate complex parameter spaces, predict stable structures, and accelerate the discovery of new catalysts [22] [21].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Catalyst Synthesis and Study.

| Reagent/Material | Function in Research | Example Application |

|---|---|---|

| Metal-Organic Frameworks (MOFs) | Sacrificial templates and precursors for porous carbon supports. | ZIF-8 used to create N-doped carbon for anchoring Pt, Fe, or Co single atoms [23]. |

| Heteroatom Dopants (e.g., KSCN, PPh(_3)) | Sources of heteroatoms (S, O, P) to create asymmetric coordination in SACs. | KSCN used to synthesize Fe(1)-N(4)SO(_2)/NC sites [23]. |

| Metal Acetylacetonates (e.g., Pt(acac)(_2)) | Common metal precursors for the synthesis of both nanoparticles and SACs. | Co-loaded with Fe(acac)(3) in ZIF-8 to create Fe-N(4)/Pt-N(_4) sites [23]. |

| Ammonia (NH(_3)) | Used in thermal treatment to create nitrogen functionalities on carbon supports. | Pyrolysis under NH(_3) creates N-doped carbon from polymer precursors [23]. |

| Triphenylphosphine (PPh(_3)) | Molecular precursor for phosphorus doping. | Encapsulated in MOF cages to create Co-SA/P catalysts with P coordination [23]. |

Experimental Workflows

Synthesis of Asymmetrically Coordinated Single-Atom Catalysts

A common strategy for creating SACs with asymmetric coordination involves pyrolyzing a metal-impregnated precursor.

Detailed Protocol:

- Precursor Preparation: A porous support, such as the metal-organic framework ZIF-8, is selected for its high surface area and nitrogen content [23].

- Impregnation: The support is immersed in a methanol solution containing both the metal precursor (e.g., ferrocene, FeCp(_2)) and a heteroatom precursor (e.g., potassium thiocyanate, KSCN, for S/O doping). The mixture is stirred to ensure uniform dispersion [23].

- Drying: The solvent is slowly evaporated to obtain a dry, homogeneous precursor powder where the metal and dopant are distributed within the MOF pores.

- Thermal Activation (Pyrolysis): The precursor is placed in a tube furnace and heated to a high temperature (e.g., 950 °C) under an inert atmosphere (N(2) or Ar) for a set time (e.g., 3 hours). This step carbonizes the organic framework, reduces the metal, and incorporates the heteroatom into the carbon matrix, forming the stable asymmetric coordination site (e.g., Fe(1)-N(4)SO(2)) [23].

- Post-processing: The resulting solid may be acid-washed to remove any unstable metal aggregates, leaving only the atomically dispersed species.

Workflow for Probing Coordination Environments via Solid-State NMR

Solid-state NMR is a powerful technique for characterizing coordination environments, especially for NMR-active metals like (^{195})Pt.

Detailed Protocol:

- Sample Preparation: The catalyst powder (e.g., Pt single atoms on N-doped carbon, Pt@NC) is packed into a solid-state NMR rotor [24].

- Data Acquisition: Using state-of-the-art ultra-wideline NMR methodology under static conditions or with magic-angle spinning (MAS) at low temperatures and fast repetition rates, the broad (^{195})Pt NMR spectrum is acquired. This can take from several hours to days, depending on Pt concentration [24].

- Spectral Analysis: The observed "powder pattern" is characterized by its tensor parameters: the isotropic chemical shift (δ(_{iso})), the span (Ω), and the skew (κ). These parameters are reporters of the local Pt environment, including oxidation state, geometry, and ligands [24].

- Modeling and Simulation: To account for site heterogeneity, the experimental spectrum is fitted using Monte Carlo simulations that model a distribution of chemical shift tensors. Inputs from DFT calculations help constrain possible coordination structures [24].

- Structural Insight: The final output is a quantitative assessment of the Pt-site distribution and homogeneity, describing coordination environments with molecular precision and tracking changes induced by synthesis or reaction conditions [24].

The distinction between nanoparticles and single-atom catalysts represents a fundamental divide in catalyst architecture, with direct consequences for electronic structure and coordination environment. Nanoparticles leverage metallic ensemble effects and a distribution of sites, making them versatile for complex reactions. In contrast, SACs offer ultimate atomic efficiency and a precisely tunable, molecular-like active site, enabling exceptional selectivity and activity for specific transformations. The choice between these platforms depends on the reaction of interest: NP ensembles may be superior for complex, multi-step reactions requiring different sites, while SACs are ideal for reactions where a specific, optimized interaction with a single intermediate is rate-determining. Future research will focus on bridging these paradigms—for instance, by designing single-atom alloys or integrative catalytic pairs that combine the advantages of both sites to drive more efficient and sustainable chemical processes [1] [13].

Synthesis, Characterization, and Application-Driven Catalyst Design

The pursuit of optimal catalyst performance has driven the development of sophisticated synthesis strategies that precisely control material architecture across multiple length scales. In contemporary catalysis research, particularly in the evolving comparison between single-crystal and nanoparticle catalysts, synthesis methodology has become a critical determinant of catalytic behavior. Bottom-up approaches construct materials from molecular or atomic precursors, enabling precise control over atomic composition. Conversely, top-down methods break down bulk materials to nanoscale dimensions, often favoring high-volume production. Uniting these paradigms, spatial confinement strategies have emerged as a powerful method to engineer local microenvironments within host matrices, significantly altering catalyst stability and reactivity.

The fundamental distinction between these synthetic philosophies lies in their starting points and control mechanisms. Bottom-up synthesis offers unparalleled precision in creating tailored active sites, including single atoms and defined nanoclusters, but faces challenges in scalability and structural uniformity. Top-down techniques provide more straightforward nanocrystal production but often lack the fine control over atomic coordination. Spatial confinement hybridizes these concepts by creating nanoscale reactors within porous frameworks or layered structures, where the confined space itself becomes a design parameter that stabilizes metastable states and enhances catalytic selectivity. This guide systematically compares these three strategic approaches, providing researchers with a quantitative framework for selecting synthesis methodologies based on desired catalytic performance metrics.

Comparative Analysis of Synthesis Techniques

Table 1: Fundamental Characteristics and Applications of Synthesis Techniques

| Synthesis Technique | Fundamental Principle | Typical Catalytic Structures Formed | Key Advantages | Primary Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bottom-Up | Assembly from molecular/atomic precursors | Single atoms, sub-nanometer clusters, nanoparticles, thin films | Atomic-level precision, high compositional control, uniform dispersions | Scalability challenges, potential metastable phases, complex synthesis protocols |

| Top-Down | Physical or chemical breakdown of bulk materials | Nanoparticles, nanorods, quantum-sized particles | Simplicity for some materials, compatible with high-volume production | Limited control over atomic structure, surface defects, broad size distribution |

| Spatial Confinement | Restriction of catalyst growth/operation within nanoscale spaces | Zeolite-encapsulated metals, layered structure composites, MOF-encapsulated catalysts | Enhanced stability, unique selectivity, suppressed leaching, stabilized intermediates | Complex host synthesis, potential diffusion limitations, reduced accessibility |

Table 2: Quantitative Performance Comparison of Catalysts Prepared by Different Techniques

| Synthesis Technique | Catalyst Example | Reaction Performance | Stability Metrics | Experimental Evidence |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bottom-Up (Single Atoms) | Pt Single Atoms on TiO₂ [25] [8] | Higher selectivity in hydrogenation vs. nanoparticles | Variable thermal stability, potential aggregation | CO-DRIFTS, HAADF-STEM, XAS confirmation of isolated sites |

| Bottom-Up (Core-Shell) | Au-Pd Core-Shell NPs [26] | ~3.5× higher activity than monometallic Pd in selective hydrogenation | Structural stability in liquid phase | Colloidal synthesis with precise structural control |

| Spatial Confinement | FeOF in GO membrane [27] | Near-complete pollutant removal for >2 weeks in flow-through operation | Significantly reduced fluoride ion leaching (primary deactivation cause) | Angstrom-scale rejection of organic matter, sustained radical availability |

| Spatial Confinement | Zeolite-confined sites for lactide production [28] | Enhanced reaction rates and stereochemical control | Stable cyclic transition states | DFT calculations showing reduced energy barriers in confined spaces |

Methodological Deep Dive: Experimental Protocols and Workflows

Bottom-Up Synthesis: Controlled Formation of Supported Platinum Structures

The preparation of defined platinum structures on titania support exemplifies the precision achievable through bottom-up methodologies. The Strong Electrostatic Adsorption (SEA) approach enables controlled deposition of Pt single atoms, sub-nanometer clusters, and nanoparticles by varying precursor loading [25]. The protocol begins with functionalization of the TiO₂ (anatase) support surface to create specific charge characteristics. A tetraammineplatinum(II) nitrate (TAPN) precursor solution is prepared with concentrations ranging from 0.04 to 5.00 wt.% Pt relative to the support mass. The precisely controlled pH adjustment ensures optimal electrostatic interaction between the precursor complex and support surface. Following immersion and stirring, the material is washed, dried, and subjected to thermal treatment (300°C under flowing air) to decompose the precursor and form the final Pt structures. Critical characterization involves HAADF-STEM for direct imaging of metal species, X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy for chemical state analysis, and CO chemisorption with DRIFTS to distinguish between single atoms, clusters, and nanoparticles based on their distinct CO adsorption signatures.

Spatial Confinement: Fabrication of FeOF-Graphene Oxide Catalytic Membranes

The creation of spatially confined catalysts represents a hybrid approach that leverages both bottom-up assembly and confinement principles. For the iron oxyfluoride (FeOF) catalytic membrane system [27], the synthesis begins with the preparation of FeOF catalysts through a solvothermal method where FeF₃·3H₂O is heated in methanol medium at 220°C for 24 hours in an autoclave. Simultaneously, single-layer graphene oxide (GO) is prepared via modified Hummers' method. The catalytic membrane is fabricated by intercalating the pre-synthesized FeOF catalysts between layers of graphene oxide through vacuum-assisted filtration, creating aligned nanochannels with angstrom-scale dimensions. The confinement effect is precisely controlled by manipulating the interlayer spacing through GO concentration and filtration parameters. The resulting membrane operates in flow-through mode, where pollutants encounter confined FeOF catalysts that activate H₂O₂ to generate hydroxyl radicals (*OH) while the membrane channels simultaneously reject natural organic matter via size exclusion. Performance validation includes long-term pollutant degradation experiments, elemental leaching analysis via ICP-OES/IC, and radical trapping with EPR spectroscopy.

Computational Guidance: DFT Analysis of Confined Catalysis

Density functional theory (DFT) calculations provide crucial theoretical support for understanding spatial confinement effects [28]. For zeolite-based systems, the workflow employs the Vienna ab initio simulation package (VASP) with the PAW method and GGA-PBE functional. A plane-wave cutoff energy of 450 eV is typically used with Gamma-point sampling. The zeolite framework is modeled using cluster or periodic approaches, with reaction pathways and energy barriers calculated for both confined and open environments. This approach has revealed that spatial confinement significantly reduces energy barriers for key reactions like lactide formation by stabilizing cyclic transition states and suppressing side reactions. Computational guidance is now being integrated with emerging natural language processing (NLP) techniques to accelerate catalyst screening, as demonstrated in SA catalyst selection for Na-S batteries [29].

Visualization of Synthesis Pathways and Confinement Effects

Synthesis Technique Decision Pathway

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Key Research Reagents and Materials for Advanced Catalyst Synthesis

| Reagent/Material | Function in Synthesis | Specific Application Examples | Critical Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Tetraammineplatinum(II) nitrate (TAPN) | Metal precursor for precise deposition | Preparation of Pt single atoms, clusters, and nanoparticles via SEA [25] | Concentration controls final metal size (single atoms at low loading) |

| Graphene Oxide (GO) | 2D confinement matrix | Creating angstrom-scale channels for FeOF catalyst confinement [27] | Layer spacing determines molecular exclusion properties |

| Zeolites (e.g., H-Beta) | Microporous crystalline host | Spatial confinement for lactide production [28] | Pore topology dictates transition state stabilization |

| Polyvinylpyrrolidone (PVP) | Colloidal stabilizer and shape-directing agent | Synthesis of Au-Pd core-shell nanoparticles [26] | Molecular weight affects binding strength and nanoparticle morphology |

| Sodium Citrate | Reducing agent and capping ligand | Controlled synthesis of gold nanoparticle cores [26] | Concentration and temperature determine final nanoparticle size |

| Ascorbic Acid | Mild reducing agent | Selective reduction in Pd overgrowth on Au cores [26] | pH sensitivity requires careful control during reduction |

| Metal-Fluoride Precursors (FeF₃·3H₂O) | Catalyst precursor for highly active phases | Synthesis of iron oxyfluoride (FeOF) catalysts [27] | Solvothermal conditions required for crystalline phase formation |

The comparative analysis presented in this guide demonstrates that bottom-up, top-down, and spatial confinement strategies each occupy distinct yet complementary roles in advanced catalyst synthesis. Bottom-up approaches provide the precision necessary for creating well-defined active sites at atomic scales, particularly valuable for fundamental mechanistic studies and applications requiring maximum atomic efficiency. Top-down methods offer practical pathways for nanoscale catalyst production, though with more limited control over atomic coordination. Spatial confinement has emerged as a particularly powerful strategy for enhancing catalyst stability—a critical limitation in many practical applications—while maintaining and often enhancing catalytic activity.

The most promising future developments lie in the strategic integration of these approaches, such as creating precisely defined active sites through bottom-up synthesis and subsequently stabilizing them within confined environments. This hybrid philosophy leverages the respective strengths of each methodology while mitigating their individual limitations. Furthermore, the growing integration of computational guidance, including both first-principles calculations and emerging machine learning approaches [29], promises to accelerate the discovery and optimization of next-generation catalytic materials. As the distinction between single-crystal and nanoparticle catalysts continues to blur with advancing characterization and synthesis capabilities, the methodological framework presented here provides researchers with a rational foundation for selecting and implementing synthesis strategies tailored to specific catalytic challenges.

In the field of catalysis, the fundamental debate between using well-defined single crystals versus complex nanoparticles as model systems continues to drive research innovation. Single crystals provide perfectly defined surfaces for understanding atomic-level reaction mechanisms, while nanoparticles offer the high surface areas and complex active sites required for industrial applications. Bridging the knowledge gap between these domains requires sophisticated characterization techniques that can reveal structural, electronic, and morphological properties across multiple length scales. This guide examines four powerful characterization methods—HAADF-STEM, XAS, XRD, and BET surface area analysis—that enable researchers to correlate catalyst structure with performance, thereby accelerating the development of next-generation catalytic systems.

Technique Fundamentals and Comparative Analysis

Core Principles of Each Characterization Method

HAADF-STEM (High-Angle Annular Dark-Field Scanning Transmission Electron Microscopy) is an advanced imaging technique that uses a focused electron beam scanned across a specimen. It collects high-angle, incoherently scattered electrons using an annular detector, producing images where intensity is approximately proportional to the square of the atomic number (Z-contrast), allowing heavy elements to appear brighter than light ones [30] [31]. This technique provides atomic-resolution imaging with easily interpretable contrast and is particularly valuable for locating heavy metal atoms or nanoparticles on lighter supports.

XAS (X-ray Absorption Spectroscopy) measures the absorption coefficient of a material as a function of X-ray energy, providing information about the oxidation state, coordination chemistry, and local electronic structure of elements. It is element-specific and can be performed under operando conditions [32] [33] [34].

XRD (X-ray Diffraction) analyzes the diffraction patterns produced when X-rays interact with crystalline materials, providing information about crystal structure, phase composition, lattice parameters, and crystallite size. It is a bulk technique that averages structural information over the entire sample volume [32] [33].

BET Surface Area Analysis (named after Brunauer, Emmett, and Teller) determines the specific surface area of porous materials by measuring the quantity of gas molecules (typically nitrogen) adsorbed as a monolayer on the material surface. It provides crucial information about catalyst porosity and available surface sites [33].

Table 1: Technical Capabilities and Limitations of Characterization Techniques

| Technique | Spatial Resolution | Element Specificity | Key Information Obtained | Main Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HAADF-STEM | Atomic-scale (~0.05 nm) [30] | No (but Z-contrast) | Atomic structure, particle size/distribution, defects | Light elements difficult to observe [30]; requires high vacuum |

| XAS | None (bulk average) | Yes | Oxidation state, local coordination environment, electronic structure | Limited spatial information; requires synchrotron source |

| XRD | None (bulk average) | No | Crystal structure, phase identification, crystallite size | Requires crystalline materials; amorphous phases not detected |

| BET Analysis | None (bulk average) | No | Specific surface area, pore volume, pore size distribution | Surface chemistry information limited |

Performance Comparison in Catalyst Characterization

Each characterization technique provides unique insights into catalyst properties, and their combined application offers a comprehensive understanding of structure-property relationships. The following table illustrates how these techniques address different aspects of catalyst characterization, with examples from recent research.

Table 2: Application of Characterization Techniques in Catalyst Analysis

| Technique | Single Crystal Studies | Nanoparticle Catalyst Studies | Complementary Data |

|---|---|---|---|

| HAADF-STEM | Limited application | Visualizes nanoparticles (7-8 nm) and atomic dispersion [33]; identifies single atoms & clusters [34] | Combined with EELS for elemental analysis [30] |

| XAS | Reference spectra | Identifies Fe-N coordination in Fe-N-C catalysts [34]; determines valence states [33] | Complements XRD for amorphous phases |

| XRD | Long-range order analysis | Identifies metallic Co phases (JCPDS #15-0806) [33]; monitors structural evolution during synthesis [33] | Combined with XAS for operando studies [32] |

| BET Analysis | Limited application (low surface area) | Measures high surface areas (e.g., 1261 m²·g⁻¹ for ZIF-derived catalysts) [33] | Correlates surface area with catalytic activity |

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

HAADF-STEM Imaging Protocol

Sample Preparation: Disperse catalyst powder in ethanol via ultrasonication. Deposit onto holy carbon TEM grids. Allow to dry completely [33] [34].

Instrument Conditions: Use aberration-corrected STEM. Typical convergence semi-angle α: ~25 mrad at 200 kV. Detector inner semi-angle β1: ~50 mrad. Detector outer semi-angle β2: ~200 mrad [30].

Image Acquisition: Align instrument optics carefully. Acquire images in synchronism with incident probe position. Integrate intensities from high-angle scattered electrons [30].

Data Interpretation: Interpret image contrast based on Z-dependence (intensity ∝ Z¹‧⁷ to Z²). Identify heavy elements as brighter regions. Use ABF-STEM simultaneously for light element detection [31].

XAS Measurement Procedure

Sample Preparation: Prepare uniform catalyst thin layer on appropriate substrate. Optimize thickness to achieve optimal absorption edge step.

Data Collection: Collect data at synchrotron facility. Measure X-ray absorption near-edge structure (XANES) and extended X-ray absorption fine structure (EXAFS). Use appropriate reference compounds for calibration [33] [34].

Data Analysis: Process data using standard software (e.g., Athena, Artemis). Extract oxidation state information from XANES edge position. Determine coordination numbers and bond distances from EXAFS Fourier transforms [34].

XRD Analysis Methodology

Sample Preparation: Grind powder samples to uniform consistency. Load into sample holder ensuring flat surface.

Measurement Parameters: Use Cu Kα radiation (λ = 1.5418 Å). Typical 2θ range: 5-90°. Step size: 0.01-0.02°. Counting time: 1-2 seconds per step [33].

Data Analysis: Identify crystalline phases using reference databases (e.g., JCPDS). Apply Scherrer equation for crystallite size determination: D = Kλ/(βcosθ), where K is shape factor (~0.9), λ is X-ray wavelength, β is FWHM, and θ is Bragg angle [33] [35].

BET Surface Area Measurement

Sample Preparation: Degas sample under vacuum at elevated temperature (typically 150-300°C) for several hours to remove contaminants.

Measurement: Measure nitrogen adsorption isotherms at 77 K. Record adsorption points at relative pressures (P/P₀) from 0.05 to 0.3.

Data Analysis: Apply BET equation to adsorption data in relative pressure range 0.05-0.3. Calculate monolayer volume. Determine specific surface area using cross-sectional area of nitrogen molecule (0.162 nm²) [33].

Research Reagent Solutions and Essential Materials

Table 3: Essential Research Materials for Advanced Catalyst Characterization

| Material/Reagent | Function in Characterization | Application Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Holy Carbon TEM Grids | Sample support for electron transparency | HAADF-STEM sample preparation [33] |

| Zeolitic Imidazolate Frameworks (ZIFs) | Precursors for well-defined catalyst supports | Synthesis of metal-N-C catalysts [33] |

| Ethylene Glycol | Reducing agent and solvent in polyol synthesis | Preparation of uniform Pt nanoparticles [36] |

| Nitrogen Gas (99.999%) | Adsorptive for surface area measurements | BET surface area analysis [33] |

| Reference Compounds (FePc, Fe foil) | Standards for calibration and comparison | XAS measurements for valence state analysis [34] |

Visualization of Characterization Workflows

Integrated Characterization Approach for Catalyst Development

Integrated Characterization Workflow for Catalyst Development

Technique Selection Logic for Catalyst Analysis

Technique Selection Logic for Catalyst Analysis

The comprehensive characterization of catalysts requires a multi-technique approach that leverages the complementary strengths of HAADF-STEM, XAS, XRD, and BET analysis. While single crystal studies continue to provide fundamental insights into reaction mechanisms, the advancement of nanoparticle catalysts demands characterization methods that can resolve complex structural and electronic features across multiple length scales. The integration of these techniques enables researchers to establish robust structure-activity relationships, guiding the rational design of next-generation catalysts with enhanced performance and stability. As characterization methodologies continue to advance, particularly with the development of in situ and operando capabilities, our ability to correlate catalyst structure with function under realistic working conditions will dramatically improve, accelerating the development of efficient catalytic processes for energy and environmental applications.

In the realm of biomedicine, the precise engineering of catalytic materials at the atomic and nanoscale has opened new frontiers in targeted therapeutic and diagnostic applications. The fundamental distinction between single crystal and nanoparticle catalysts lies in their structural configuration and resulting physicochemical properties. Single crystal catalysts, characterized by a long-range, continuous ordered structure, provide uniform surface active sites ideal for consistent catalytic behavior. In contrast, nanoparticles are discrete entities with high surface-to-volume ratios, often exhibiting quantum confinement effects and a high density of low-coordination surface sites. This structural dichotomy creates a fascinating trade-off: while single crystals offer precision and reproducibility, nanoparticles provide versatility and high reactivity. Within nanoparticle categories, a further distinction exists between single-atom catalysts (SACs), where isolated metal atoms are anchored on supports, and nanoparticle catalysts (NPCs), which consist of metal clusters. Single atoms demonstrate maximized atomic efficiency and unique electronic properties due to their low coordination environment, whereas nanoparticles benefit from cooperative effects between adjacent metal atoms [8]. This comparative analysis examines how these distinct catalyst architectures perform across three critical biomedical applications: targeted drug delivery, hyperthermia therapy, and biosensing platforms, providing researchers with experimental data and methodologies to guide material selection for specific biomedical challenges.

Performance Comparison Tables

Table 1: Comparative Performance of Catalyst Types in Biomedical Applications

| Application | Catalyst Type | Key Performance Metrics | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Targeted Drug Delivery | Iron Oxide Nanoparticles (IONPs) | • Drug loading capacity: Varies with surface functionalization• Enhanced permeability and retention (EPR) effect: Passive tumor targeting• Magnetic guidance: External field-responsive delivery [37] | • High saturation magnetization for targeting• Biocompatible with proper coating• Multi-functional platform | • Potential biocompatibility and toxicity issues• Agglomeration without surface modification• Limited drug loading capacity |

| Thermosensitive Nanocarriers | • LCST/UCST behavior: Phase transition at 39-42°C• Drug release: Triggered by mild hyperthermia [38] | • Spatiotemporal control of drug release• Minimal off-target effects• Combination therapy capability | • Complex synthesis procedures• Potential polymer toxicity• Heat distribution challenges in tissues | |

| Hyperthermia Therapy | Magnetic Nanoparticles (MNPs) | • SAR (Specific Absorption Rate): Determines heating efficiency• Intrinsic Loss Power (ILP): Standardized comparison metric• Heating temperature: 41-46°C for therapeutic effect [39] | • Deep tissue penetration• Precise temperature control• Minimal invasiveness | • Potential overheating risks• Optimization of magnetic properties needed• Challenges in uniform heat distribution |

| Single-Atom Catalysts | • Atom utilization: ~100% efficiency• Coordination environment: Tunable electronic properties [8] [40] | • Maximum atomic efficiency• Tailorable electronic structure• Unique catalytic selectivity | • Synthesis stability challenges• Potential metal leaching• Limited to specific catalytic reactions | |

| Biosensing | Electrochemical Biosensors | • Sensitivity: Enhanced by nanostructured electrodes• Specificity: Biorecognition element dependent• Response time: Short with proper design [41] [42] | • High sensitivity and specificity• Rapid response times• Compatibility with miniaturization | • Fouling in complex media• Enzyme instability• Calibration drift over time |

| Optical Biosensors | • Detection limit: PPM to PPB range achievable• Signal transduction: Plasmonic, fluorescent, colorimetric [42] | • High detection sensitivity• Multiplexing capability• Real-time monitoring | • Instrument complexity• Interference from ambient light• Higher cost than electrochemical |

Table 2: Experimental Performance Data for Catalyst Systems in Biomedical Applications

| Catalyst System | Composition/Structure | Application | Performance Results | Experimental Conditions |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| IONPs-based System | Fe₃O₄ with polymer coatings (chitosan, dextran, PEG) [37] | Drug Delivery & MRI | • High saturation magnetization (80-92 emu)• Enhanced contrast in T2-weighted MRI• Successful drug transport with minimal loss | • In vivo studies using U87MG xenografted tumor model• MRI analysis at various time points |

| MOF-Derived Co/NC Catalyst | Co single atoms + Co nanoparticles on N-doped carbon [40] | Photothermal CO₂ Methanation | • CO₂ conversion: 39.3%• CH₄ production rate: 21.6 mmol g⁻¹ h⁻¹• CH₄ selectivity: 94.3% | • Concentrated solar light (1.55 W cm⁻²)• Xenon lamp simulation• Fresnel lens concentration |

| Self-healing Cu SAC | CuN₄ to CuN₁O₂ reconstruction with ZrO₂ clusters [43] | Electrocatalytic CO₂ Methanation | • Faradaic efficiency: 87.06% at -500 mA cm⁻²• 80.21% at -1000 mA cm⁻²• <3% activity decay over 25h | • Membrane electrode assembly (MEA) electrolyzer• Stability test at 500 mA cm⁻² |

| Thermosensitive Liposomes | DPPC-based lipids (Tm ≈ 41.5°C) [38] | Drug Delivery + Hyperthermia | • Rapid drug release at 41-42°C• Enhanced tumor permeability• Synergistic effect with hyperthermia | • Localized heating via MR-HIFU• In vivo tumor models |

| Electrochemical Biosensors | Nanostructured electrodes with enzymes [41] [42] | Glucose Monitoring | • CAGR of 7.00-9.1% in market growth• High specificity in complex media• Continuous monitoring capability | • Point-of-care testing conditions• Various biological samples |

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Synthesis and Functionalization of Iron Oxide Nanoparticles (IONPs)

The preparation of IONPs for biomedical applications requires precise control over size, morphology, and surface properties to ensure optimal performance and biocompatibility. The co-precipitation method represents the most common approach, involving the simultaneous precipitation of Fe²⁺ and Fe³⁺ ions in a basic aqueous solution under inert atmosphere. The critical parameters include temperature (70-80°C), pH (8-14), and the Fe²⁺/Fe³⁺ ratio (typically 1:2). Following synthesis, surface functionalization is essential to improve stability and biocompatibility. Coating with organic polymers like chitosan, dextran, polyethylene glycol (PEG), or polyvinyl alcohol creates a protective layer that reduces agglomeration and prevents recognition by the immune system. For targeted drug delivery, IONPs are further functionalized with specific ligands (e.g., antibodies, peptides) that recognize biomarkers on target cells. The drug loading capacity is determined by incubating the functionalized IONPs with the therapeutic agent, followed by purification to remove unbound drugs. quantification of drug loading is typically performed using UV-Vis spectroscopy or HPLC [37].

Evaluation of Hyperthermia Efficiency in Magnetic Nanoparticles

The assessment of heating efficiency in magnetic nanoparticles for hyperthermia applications follows standardized protocols to enable meaningful comparisons between different systems. The specific absorption rate (SAR) is the key parameter, defined as the amount of heat generated per unit mass of magnetic material under an alternating magnetic field (AMF). Experimentally, MNPs are dispersed in an aqueous medium at a known concentration and exposed to an AMF with specific frequency (f) and amplitude (H). The temperature rise is monitored using a fiber-optic thermometer to avoid interference with the magnetic field. The SAR value is calculated using the formula: SAR = C × (ΔT/Δt) × (msuspension/mmagnetic), where C is the specific heat capacity of the suspension, ΔT/Δt is the initial slope of the temperature versus time curve, msuspension is the mass of the suspension, and mmagnetic is the mass of the magnetic material in the suspension. To enable comparison between different experimental conditions, the intrinsic loss power (ILP) is calculated by normalizing the SAR with respect to the field parameters: ILP = SAR/(f × H²). This normalized parameter accounts for variations in AMF conditions and allows direct comparison of the intrinsic heating efficiency of different MNPs [39].

Fabrication and Characterization of Electrochemical Biosensors

The development of electrochemical biosensors for medical diagnostics involves the precise integration of biological recognition elements with transducer surfaces. The protocol begins with substrate preparation, typically using glassy carbon or highly oriented pyrolytic graphite (HOPG) as support material. The substrate undergoes rigorous cleaning through physical polishing with alumina slurry (¼ μm to 0.04 μm grain size) followed by chemical treatment with nitric acid to create nanometrical variations in electrode roughness that stabilize nanoparticle deposition. For nanoparticle-based biosensors, size-selected nanoparticles are deposited onto the substrate at extremely low loadings (150-500 ng cm⁻²) to minimize agglomeration and ensure reproducible results. The biological recognition element (enzyme, antibody, DNA strand) is then immobilized onto the electrode surface using various techniques including physical adsorption, covalent bonding, or cross-linking with glutaraldehyde. Performance characterization involves measuring sensitivity, detection limit, selectivity, and stability. Amperometric measurements are conducted at fixed potentials while recording current response to analyte addition, with calibration curves established using standard solutions. Selectivity is assessed by challenging the biosensor with potential interferents commonly found in the sample matrix [44] [41].

Signaling Pathways and Experimental Workflows

Catalyst-Driven Therapeutic Pathways

Nanoparticle Synthesis & Characterization Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for Biomedical Catalyst Studies

| Category | Specific Materials | Function/Purpose | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|---|

| Support Materials | Glassy Carbon | Electrode substrate for biosensors | • High conductivity• Chemical inertness• Polishing capability to mirror finish [44] |

| Highly Oriented Pyrolytic Graphite (HOPG) | Support for nanoparticle deposition | • Atomically flat surface• Excellent for STM characterization• High electrical conductivity [44] | |

| Coating Polymers | Chitosan | Biopolymer coating for IONPs | • Biocompatibility• Mucoadhesive properties• Functional groups for conjugation [37] |

| Polyethylene Glycol (PEG) | Surface functionalization | • "Stealth" properties reduce immune recognition• Improved circulation time• Biocompatibility [37] | |

| Dextran | Polysaccharide coating for IONPs | • Hydrophilicity• Biodegradability• FDA-approved for some applications [37] | |

| Magnetic Components | Iron Oxide (Fe₃O₄, γ-Fe₂O₃) | Core material for hyperthermia & drug delivery | • Superparamagnetism at nanoscale• High saturation magnetization• Biodegradability [37] |

| Thermosensitive Materials | DPPC (Dipalmitoylphosphatidylcholine) | Lipid for thermosensitive liposomes | • Phase transition temperature ~41.5°C• Enhanced permeability above Tm [38] |

| PNIPAM (Poly(N-isopropylacrylamide)) | Thermoresponsive polymer | • LCST ~32°C (adjustable to 40-42°C)• Reversible phase transition• Tunable drug release properties [38] | |

| Characterization Reagents | Argon Ions (Ar⁺) | Surface cleaning in UHV | • Sputtering to remove top atomic layers• Surface preparation for deposition [44] |

| Nitric Acid (HNO₃) | Substrate cleaning and etching | • Removal of metal contaminants• Creating nanoscale roughness for nanoparticle stabilization [44] |