Surface Plasmon Resonance Applications: From Drug Discovery to Point-of-Care Diagnostics

This article provides a comprehensive overview of the transformative applications of Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR) technology in biomedical research and pharmaceutical development.

Surface Plasmon Resonance Applications: From Drug Discovery to Point-of-Care Diagnostics

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive overview of the transformative applications of Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR) technology in biomedical research and pharmaceutical development. Tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, it explores the foundational principles of SPR, its critical role in real-time, label-free biomolecular interaction analysis, and its diverse methodological applications from high-throughput drug screening to clinical diagnostics. The content further addresses common experimental challenges and optimization strategies, validates SPR performance against emerging trends and comparative studies, and synthesizes key insights to forecast future directions in personalized medicine and point-of-care testing.

Understanding Surface Plasmon Resonance: Core Principles and Sensing Mechanisms

Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR) is an optical phenomenon arising from the collective oscillation of free electrons at the interface between a metal and a dielectric material [1] [2]. When these conductive electrons, often referred to as surface plasmon polaritons (SPPs), interact with incident light under specific conditions, they create a charge density wave that propagates along the metal-dielectric boundary [1]. This resonance stems from the interaction of light with free electrons under certain conditions, where the SPP oscillations are associated with an electric field propagating along the metal-dielectric interface and decaying exponentially in the perpendicular direction [1]. The energy is predominantly confined to the metal surface, which explains the remarkable sensitivity of SPR to changes in optical parameters at the metal-dielectric boundary [1].

This physical phenomenon provides the foundation for powerful sensing technologies that monitor biomolecular interactions in real-time without requiring labels [3]. SPR-based biosensing represents one of the most advanced label-free, real-time detection technologies available to researchers today [1]. The technology's exceptional sensitivity to minute changes in refractive index at the metal surface has enabled its widespread adoption across pharmaceutical research, diagnostic development, and life sciences [4].

Fundamental Principles and Key Parameters

The theoretical foundation of SPR relies on three essential characteristics that govern sensor design and performance: electric field enhancement, propagation length, and penetration depth [1].

Electric Field Enhancement

At the resonance angle, the intensity of the electric field at the interface between the metal and dielectric is significantly enhanced compared to the incident light [1]. This enhancement occurs due to the smaller complex permittivity in the dielectric compared to that in the metal and depends critically on the thickness and optical properties of the materials used [1]. This enhanced field is responsible for the exceptional sensitivity of SPR measurements.

Propagation Length

The surface plasmon polariton propagates along the interface with a characteristic decay length. For a gold-air interface at 648 nm wavelength, the propagation distance is approximately 17.4 μm, while for a gold-water interface it reduces to 6.6 μm [1]. This propagation length represents a fundamental limitation for SPR imaging resolution and is governed by the complex wavevector of the SPP, which includes both real and imaginary components related to wave attenuation through metal absorption and radiative losses [1].

Penetration Depth

The electromagnetic field associated with SPPs decays exponentially in the direction perpendicular to the interface. The penetration depth, defined as the distance where the field intensity decays to 1/e (approximately 37%) of its value at the interface, differs significantly between the metal and dielectric sides [1]. For a gold film at 648 nm excitation, the penetration depth is 191 nm in water, 351 nm in air, but only 27 nm into the gold layer itself [1].

Table 1: Key Parameters of Surface Plasmon Polaritons at Gold Interfaces (λ₀ = 648 nm)

| Parameter | Definition | Gold-Air Interface | Gold-Water Interface |

|---|---|---|---|

| Propagation Length (δSPP) | Distance SPP travels before decaying | 17.4 μm | 6.6 μm |

| Penetration Depth into Dielectric (δd) | Field decay into dielectric | 351 nm | 191 nm |

| Penetration Depth into Metal (δm) | Field decay into metal | 27 nm | 27 nm |

| Electric Field Enhancement | Field intensity at interface vs incident light | Significantly enhanced | Significantly enhanced |

The resonance condition for exciting surface plasmons is described by the wavevector matching equation [1]:

[ k{SPP} = \frac{2\pi}{\lambda0} \sqrt{\frac{\varepsilonm \varepsilond}{\varepsilonm + \varepsilond}} = \frac{2\pi}{\lambda0} np \sin\theta_i ]

where (k{SPP}) represents the surface plasmon wavevector, (\lambda0) the incident wavelength, (\varepsilonm) and (\varepsilond) the permittivities of metal and dielectric, respectively, (np) the refractive index of the coupling prism, and (\thetai) the incident angle of light [1].

Experimental Protocols

Standard SPR Experiment Using Kretschmann Configuration

The Kretschmann configuration remains the most widely employed method for exciting surface plasmons in analytical biosensors [1] [5]. This protocol outlines the core steps for establishing SPR measurement capability.

Materials and Equipment

- SPR instrument with optical platform and flow control system [3]

- Sensor chips (gold-coated with optional functional layers) [3]

- Coupling prism (refractive index ~1.799 at 633 nm) [5]

- Polarizer to generate P-polarized light [5]

- High-intensity light source (laser or tungsten-halogen lamp) [5]

- Microfluidic components for sample delivery [3]

- Buffer solutions for calibration and dilution (e.g., Tris-HCl, NaCl) [2]

- Cleaning reagents (NaOH, isopropanol) [2]

- Regeneration solutions (e.g., CHAPS detergent) [2]

Procedure

Step 1: System Setup and Calibration

- Mount the sensor chip onto the prism using index-matching fluid to ensure optical contact [5].

- Align the optical components to ensure precise angle or wavelength interrogation.

- Establish continuous buffer flow through the microfluidic system to maintain a stable baseline [3].

- Calibrate the system using solutions with known refractive indices (e.g., sodium chloride solutions of varying concentrations) [5].

Step 2: Surface Functionalization (Typical Amine Coupling)

- Clean the gold surface thoroughly to remove contaminants.

- Form a self-assembled monolayer on the gold surface to block nonspecific binding and provide functional groups for ligand attachment [3].

- Activate the surface using EDC/NHS or similar chemistry to create reactive esters.

- Immobilize the ligand (typically diluted in low ionic strength sodium acetate buffer, pH 4.0-5.0).

- Deactivate remaining active esters and block remaining reactive sites.

- Verify immobilization level through a brief buffer injection.

Step 3: Binding Experiment

- Establish stable baseline with running buffer.

- Inject analyte samples at controlled flow rate (typically 10-100 μL/min).

- Monitor association phase for 2-5 minutes depending on kinetics.

- Switch to running buffer to monitor dissociation phase.

- Regenerate surface if needed for repeated measurements.

- Include blank injections for reference subtraction.

Step 4: Data Analysis

- Process sensorgram by subtracting reference cell and buffer blank signals.

- Fit binding curves using appropriate kinetic models (1:1 Langmuir, bivalent, heterogeneous, etc.).

- Calculate kinetic parameters (association rate (ka), dissociation rate (kd)) and equilibrium constants (affinity (K_D)).

Advanced Protocol: Flexible SPR Sensor with PDMS Substrate

Recent innovations have demonstrated the feasibility of flexible SPR substrates, offering new applications in wearable sensing and complex surface monitoring [5].

Materials

- PDMS films (100 μm thickness) [5]

- Magnetron sputtering system for metal deposition [5]

- Chromium (3 nm) and gold (50 nm) targets [5]

- Custom sample chambers [5]

- Sodium chloride solutions for sensitivity calibration [5]

- Alcohol samples for validation (e.g., Chinese Baijiu variants) [5]

Fabrication and Measurement Procedure

Step 1: Flexible Chip Fabrication

- Clean PDMS substrate thoroughly to ensure proper metal adhesion.

- Deposit 3 nm chromium adhesion layer using magnetron sputtering.

- Deposit 50 nm gold film onto the chromium layer under controlled conditions.

- Characterize film quality and uniformity using appropriate metrology.

Step 2: Experimental Setup

- Optically couple the flexible chip to a prism using index-matching fluid.

- Position custom-designed sample chamber above the prism for analyte exposure.

- Configure spectrally resolved detection system with broadband light source.

- Fix incident angle at optimal sensitivity point (e.g., 13° as demonstrated) [5].

Step 3: Performance Validation

- Measure refractive index sensitivity using sodium chloride solutions of varying concentrations.

- Evaluate stability through bidirectional bending tests (up to 50 cycles).

- Validate analytical performance with real samples (e.g., alcohol content in beverages).

- Characterize adsorption behavior of target analytes (e.g., glutathione under varying pH).

Table 2: Performance Metrics of Flexible PDMS-based SPR Sensor

| Performance Parameter | Result | Experimental Conditions |

|---|---|---|

| Refractive Index Sensitivity | 3385.5 nm/RIU | Sodium chloride solutions |

| Angle of Incidence | 13° | Optimized for sensitivity and detection accuracy |

| Stability after Bending | 1% sensitivity variation | After 50 bidirectional bending cycles |

| Alcohol Content Detection Accuracy | 0.17-4.04% relative error | Three Chinese Baijiu samples |

| Optimal GSH Adsorption pH | pH = 12 (immediate), pH = 7 (film formation) | Glutathione on gold film |

Research Reagent Solutions

Successful SPR experimentation requires careful selection of reagents and materials optimized for specific applications. The following table details essential components for establishing SPR research capabilities.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for SPR Experiments

| Reagent/Material | Function/Application | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Sensor Chips | Platform for ligand immobilization | Gold surface with various functionalizations (carboxymethyl dextran, nitrilotriacetic acid, streptavidin) |

| Coupling Prisms | Optical component for SPR excitation | High refractive index (e.g., 1.799 at 633 nm), precise angular alignment |

| PDMS Flexible Substrates | Alternative to rigid glass substrates | 100 μm thickness, enables flexible sensing applications |

| Chromium/Gold Targets | Metal film deposition for sensor chips | 3 nm Cr adhesion layer, 50 nm Au optimal for SPR |

| EDC/NHS Chemistry | Surface activation for amine coupling | Forms reactive esters for covalent ligand immobilization |

| Running Buffers | Maintain stable baseline and sample dilution | Tris-HCl, HEPES, or PBS with appropriate ionic strength |

| Regeneration Solutions | Remove bound analyte without damaging ligand | CHAPS detergent, NaOH, glycine pH 2.0-3.0 |

| Reference Compounds | System suitability and performance verification | Well-characterized binding pairs (e.g., antibody-antigen) |

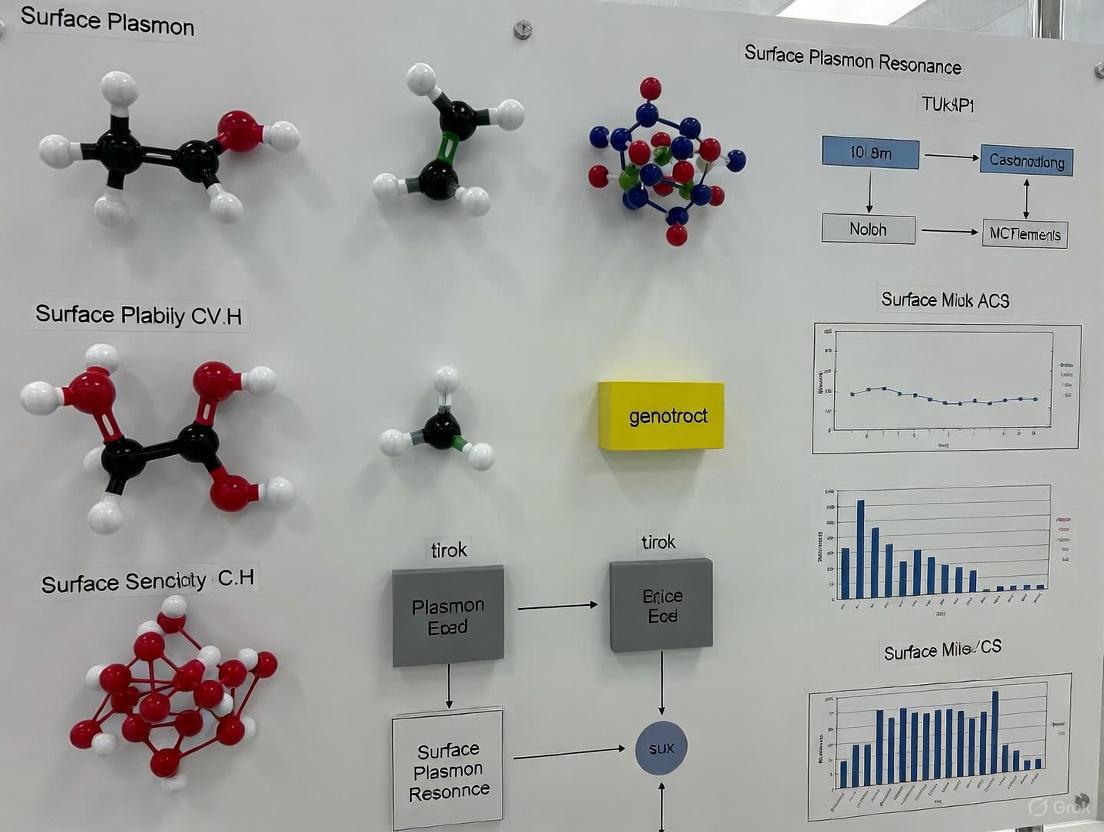

Signaling Pathways and Experimental Workflows

The following diagrams illustrate key experimental workflows and the relationship between SPR components, generated using DOT language with specified color constraints.

Diagram 1: Core SPR Instrumentation Workflow

Diagram 2: SPR Binding Experiment Cycle

Applications in Pharmaceutical Research

SPR technology has become indispensable in drug discovery and development, providing critical insights into molecular interactions that guide therapeutic optimization.

Biotherapeutic Characterization

SPR is extensively used for characterizing protein therapeutics, including monoclonal antibodies, fusion proteins, and other biologics [3]. The technology enables precise determination of binding affinity and kinetics between drug candidates and their targets, parameters that directly influence dosing regimens and efficacy profiles. SPR can detect affinities ranging from millimolar to picomolar, covering the complete spectrum of relevant drug-target interactions [3].

Small Molecule Screening

Fragment-based drug discovery heavily relies on SPR for identifying and optimizing low molecular weight compounds [4]. The label-free nature of SPR detection allows direct measurement of weak interactions that might be missed by alternative technologies. Recent innovations like frame injection technology have significantly reduced reagent costs and analysis time for small molecule screening campaigns [3].

Condition-Dependent Binding Studies

Understanding how environmental factors influence molecular interactions represents a key application of modern SPR systems [3]. By systematically varying conditions such as pH, ionic strength, or temperature, researchers can assess the robustness of interactions and predict behavior in different physiological compartments. This approach is particularly valuable for biologics that must function in diverse microenvironmental conditions.

The continued evolution of SPR instrumentation and methodology ensures this physical phenomenon of electron oscillations at metal-dielectric interfaces remains at the forefront of interaction analysis technology, enabling increasingly sophisticated applications in basic research and drug development [6] [1] [4].

Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR) is a powerful, label-free technology for the real-time analysis of biomolecular interactions. Among the various methods for exciting surface plasmons, the Kretschmann configuration has emerged as the predominant experimental setup due to its high sensitivity, operational simplicity, and robust performance [7]. This prism-based coupling technique enables direct, label-free, and dynamic monitoring of binding events, making it indispensable in fundamental research and drug development [8] [7]. This application note details the underlying principles, advanced sensor designs, and standardized protocols for implementing the Kretschmann configuration, providing a practical framework for researchers and scientists.

Principle of Operation

The Kretschmann configuration functions by exciting surface plasmon polaritons (SPPs)—collective oscillations of free electrons at a metal-dielectric interface [9] [7]. This is achieved by coupling light into a thin metal film (typically gold or silver) through a high-refractive-index prism.

When p-polarized light is incident on the prism-metal interface at an angle greater than the critical angle for total internal reflection, it generates an evanescent wave that penetrates the metal film [7]. At a specific resonance angle, the momentum of this evanescent wave matches the momentum of the surface plasmons at the opposite metal-dielectric interface [10]. This coupling results in a resonant energy transfer, manifesting as a sharp dip in the intensity of reflected light [11] [7]. The condition for resonance is given by:

$$ kx = \frac{2\pi}{\lambda} np \sin(\theta{SPR}) = \text{Re} \left( \frac{2\pi}{\lambda} \sqrt{\frac{\epsilonm \epsilond}{\epsilonm + \epsilon_d}} \right) $$

Where $kx$ is the component of the incident light's wavevector parallel to the interface, $\lambda$ is the wavelength, $np$ is the refractive index of the prism, $\theta{SPR}$ is the resonance angle, and $\epsilonm$ and $\epsilon_d$ are the dielectric constants of the metal and the dielectric sensing layer, respectively [11] [10].

Any change in the refractive index of the dielectric medium adjacent to the metal surface (e.g., due to molecular binding) alters the resonance condition, leading to a measurable shift in $\theta_{SPR}$ [8]. This physical principle is the foundation of the Kretschmann configuration's sensing capability.

This diagram illustrates the core components and logical workflow of an SPR experiment using the Kretschmann configuration.

Advanced Sensor Architectures and Performance

The basic Kretschmann structure can be enhanced with additional layers to improve sensitivity, stability, and specificity. Advanced designs incorporate dielectric spacers and two-dimensional (2D) materials to fine-tune the electromagnetic field distribution and protect the plasmonic metal.

Table 1: Performance of Advanced Kretschmann Configuration SPR Sensors

| Sensor Architecture | Sensitivity (°/RIU) | Quality Factor (RIU⁻¹) | Figure of Merit (FoM) | Limit of Detection (LoD) | Key Application |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BK7/Ag/ZnSe [12] | 451 | 173.46 | - | - | General biosensing |

| BK7/Ag/Si$3$N$4$/BP [8] | 394.46 | - | - | - | Cancer biomarker detection |

| BK7/Ag/Si/ BaTiO$_3$/DNA [9] | - | - | 692.28 | - | SARS-CoV-2 detection |

| BK7/Cu/Si$3$N$4$/MXene (Sys₃) [13] | 254 | 30-35 | - | ~2x10$^{-5}$ RIU | Breast cancer (T2) biomarker |

| BK7/Cu/MXene (Sys₄) [13] | 312 | 48-58 | - | ~2x10$^{-5}$ RIU | Breast cancer (T2) biomarker |

| BK7/Graphene/Ag/WS$_2$ [14] | 804.02 | - | - | 0.003 RIU | Brain tumor biomarker |

Key Enhancements and Material Functions

- Plasmonic Metals: Silver (Ag) provides sharper resonance and higher sensitivity, but is prone to oxidation. Gold (Au) offers superior chemical stability and easier functionalization, making it a common choice for bio-applications [9] [13]. Copper (Cu) is a lower-cost alternative with promising optical properties when protected from oxidation [13].

- Dielectric Spacers: Materials like Silicon Nitride (Si₃N₄) and Zinc Selenide (ZnSe) act as high-refractive-index layers that confine the evanescent field, sharpening the resonance dip and improving the phase-matching condition [12] [8] [13].

- Two-Dimensional (2D) Materials: MXene, Graphene, and Black Phosphorus (BP) intensify surface charge oscillations and provide a high surface-to-volume ratio for analyte adsorption, significantly boosting sensitivity [8] [14] [13].

Experimental Protocols

This section provides a generalized workflow for conducting an SPR experiment, from sensor chip preparation to data acquisition.

Protocol 1: Sensor Chip Functionalization

Objective: To prepare a sensor chip with a specific recognition element (e.g., an antibody or DNA probe) immobilized on the surface.

- Surface Cleaning: If using a new chip, clean the gold surface with a fresh piranha solution (3:1 concentrated H$2$SO$4$:30% H$2$O$2$) for 1 minute. CAUTION: Piranha is extremely corrosive and must be handled with extreme care. Rinse thoroughly with deionized water and ethanol, then dry under a stream of nitrogen.

- Surface Pretreatment: Expose the clean chip to an oxygen plasma for 1-2 minutes to create a hydrophilic surface and remove any residual organic contaminants.

- Self-Assembled Monolayer (SAM) Formation: Incubate the chip overnight in a 1 mM solution of a thiolated linker molecule (e.g., 11-mercaptoundecanoic acid) in absolute ethanol. This forms a covalent bond with the gold and creates a functionalized surface.

- Activation: Rinse the chip with ethanol and water, then place it in a flow cell. Inject a mixture of 0.4 M EDC and 0.1 M NHS in water for 7-10 minutes to activate the terminal carboxylic acid groups, forming amine-reactive esters.

- Ligand Immobilization: Dilute the ligand (e.g., protein, antibody) in a suitable immobilization buffer (e.g., 10 mM acetate buffer, pH 4.5). Inject the ligand solution over the activated surface for a sufficient time to achieve the desired immobilization level (typically 5-30 minutes).

- Deactivation and Washing: Inject 1 M ethanolamine-HCl (pH 8.5) for 7 minutes to block any remaining active esters. Finally, wash the surface with running buffer to remove non-covalently bound material.

Protocol 2: Binding Kinetics Measurement

Objective: To quantify the association and dissociation rates ($ka$ and $kd$) and the equilibrium binding affinity ($K_D$) between an immobilized ligand and an analyte in solution.

- System Equilibration: Prime the SPR instrument's fluidic system with running buffer (e.g., PBS with 0.05% surfactant). Dock the functionalized sensor chip and allow the signal to stabilize for at least 10-15 minutes to establish a stable baseline.

- Analyte Injection (Association Phase): Prepare a dilution series of the analyte in running buffer. Using an autosampler, inject each analyte concentration over the sensor surface for a fixed period (typically 1-5 minutes), during which the binding occurs and the signal increases.

- Dissociation Phase: Switch the flow back to pure running buffer. The decrease in signal is monitored for a sufficient time (typically 5-20 minutes) to track the dissociation of the complex.

- Surface Regeneration (Optional): If the complex is stable and does not fully dissociate, inject a regeneration solution (e.g., 10 mM glycine-HCl, pH 2.0-3.0) for 15-60 seconds to break the ligand-analyte bonds and return the signal to baseline. The choice of regeneration solution (acidic, basic, or ionic) must be empirically determined to be effective without damaging the immobilized ligand [15].

- Data Analysis: Double-reference the sensorgram data (subtract signals from a reference flow cell and a buffer blank). Fit the concentration series globally to a 1:1 binding model using the instrument's software to extract $ka$, $kd$, and $KD$ ($KD = kd/ka$).

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for SPR Experiments

| Item | Function / Description | Example Use Cases |

|---|---|---|

| Sensor Chips | Substrate for immobilization; various surface chemistries available [15]. | Dextran for covalent coupling; Streptavidin for capturing biotinylated molecules; Planar lipid bilayers for membrane protein studies. |

| Coupling Reagents | Activate surface functional groups for ligand attachment. | EDC (1-Ethyl-3-(3-dimethylaminopropyl)carbodiimide) and NHS (N-Hydroxysuccinimide) for amine coupling. |

| Regeneration Solutions | Remove bound analyte without damaging the immobilized ligand [15]. | Glycine-HCl (pH 2.0-3.0) for antibody-antigen pairs; NaOH (10-50 mM) for high-pH stability ligands; SDS for hydrophobic interactions. |

| Anti-Fouling Agents | Reduce non-specific binding of proteins or other components to the sensor surface. | Carboxymethyl dextran, Bovine Serum Albumin (BSA), or surfactant (e.g., Tween 20) in running buffer and sample diluent. |

| Running Buffers | Provide a stable chemical environment for the interaction. | Phosphate Buffered Saline (PBS), HEPES Buffered Saline (HBS), often with added surfactant (e.g., 0.05% P20). |

System Characterization and Data Correction

Accurate interpretation of SPR data requires an understanding of the entire system's optical response. The measured reflectance spectrum ($R{measured}$) is the product of the ideal SPR sensor response ($R{SPR}$) and the wavelength-dependent transfer functions ($H_i$) of every optical component in the setup [10]:

$$ R{measured}(\lambda) = H{Source}(\lambda) \cdot H{Polarizer}(\lambda) \cdot H{Fiber}(\lambda) \cdot H{SPR}(\lambda) \cdot H{Spectrometer}(\lambda) $$

Where:

- $H_{Source}$: Emission spectrum of the light source (modeled by Planck's law).

- $H_{Polarizer}$: Wavelength-dependent transmittance of the polarizer.

- $H_{Spectrometer}$: Combined efficiency of the diffraction grating and CCD responsivity [10].

A detailed system model that characterizes these individual transfer functions can correct the measured spectra, reduce instrumental artifacts, and extend the operational range of the sensor, which is crucial for detecting subtle refractive index changes [10].

The Kretschmann configuration remains the cornerstone of modern SPR technology due to its robust and highly sensitive platform. Ongoing innovation, particularly through the integration of novel materials like 2D semiconductors and high-index dielectrics, continues to push the boundaries of detection sensitivity and specificity. The protocols and guidelines outlined in this document provide a foundation for researchers in drug development and life sciences to reliably deploy this powerful technique for the real-time, label-free analysis of biomolecular interactions, from antibody characterization to pathogen detection.

Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR) is a powerful, label-free analytical technique that enables the real-time study of biomolecular interactions [ [16] [17]]. The technology's foundation lies in monitoring changes in optical properties at a metal-dielectric interface, typically a thin gold film, when molecules bind to its surface [ [16]]. These interactions are quantified through three primary measurable outputs: shifts in the resonance angle, changes in the resonance wavelength, and variations in the reflected light intensity at a fixed angle [ [16] [18]]. These outputs provide critical data on binding specificity, affinity (equilibrium dissociation constant, KD), and kinetics (association and dissociation rate constants, ka and kd) [ [19] [17]]. This document details the application and measurement protocols for these key outputs within the context of a broader thesis on advancing SPR biosensing applications.

The following table summarizes the core measurable outputs in SPR biosensing, their definitions, and the quantitative information they deliver.

Table 1: Key Measurable Outputs in SPR Biosensing

| Measurable Output | Physical Definition | Data Obtained | Typical Units | Measurement Configuration |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Resonance Angle Shift | The change in the incident angle of light at which surface plasmon resonance and minimal reflectivity occur [ [16]]. | Biomolecular binding affinity and kinetics [ [17]]; Sensor sensitivity [ [18]] | Degrees (°) or Resonance Units (RU) | Angular Interrogation [ [18]] |

| Resonance Wavelength Shift | The change in the wavelength of light that excites surface plasmons at a fixed incident angle [ [16]]. | Analyte concentration; Refractive Index Unit (RIU) changes [ [16]] | Nanometers (nm) | Wavelength Interrogation [ [16]] |

| Intensity Shift | The change in the intensity of light reflected at a fixed angle near the resonance condition [ [16]]. | Real-time binding events (Sensogram) [ [17]] | Response Units (RU) or % | Intensity Interrogation [ [16]] |

Experimental Protocols

General Protocol for SPR-Based Binding Kinetics Using a Streptavidin Sensor Chip

This protocol outlines the steps for measuring protein-peptide interaction kinetics using a streptavidin (SA) sensor chip, a common platform for studying biotinylated ligands [ [19]].

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Materials and Reagents

| Item | Function / Description |

|---|---|

| SPR Instrument | A five-channel system (e.g., BI-4500) capable of real-time, label-free detection [ [19]]. |

| Streptavidin Sensor Chip | The sensor surface functionalized with streptavidin for high-affinity capture of biotinylated ligands [ [19]]. |

| Proteins & Ligands | Purified analyte and biotinylated ligand. In the featured experiment: Human α-thrombin (analyte) and biotinylated peptide T10-39 (ligand) [ [19]]. |

| Running Buffer (RB) | A suitable buffer, e.g., Phosphate-Buffered Saline (PBS) or 50 mM Tris-HCl pH 7.5, 150 mM NaCl, filtered (0.22 µm) and degassed [ [19] [17]]. |

| Regeneration Solution | A solution to remove bound analyte without damaging the chip, e.g., 20 mM NaOH [ [19]]. |

Step-by-Step Methodology

Sample and Buffer Preparation

- Purify the ligand (e.g., biotinylated peptide T10-39) and analyte (e.g., human α-thrombin). Remove aggregates via gel-filtration or ultracentrifugation [ [17]].

- Prepare the Running Buffer (RB) and filter it using a 0.22 µm filter. If the system lacks an in-line degasser, degas the buffer manually [ [17]].

- Dilute the biotinylated ligand and the analyte into the RB to their working concentrations. For an unknown system, test a concentration range from 10 nM to 10 µM [ [17]].

System and Sensor Chip Preparation

- Dock a new or cleaned streptavidin sensor chip into the instrument according to the manufacturer's instructions [ [17]].

- Prime the entire fluidic system with the RB to establish a stable baseline.

- Set the temperature for the chip and, optionally, the sample compartment (e.g., 25°C for the chip, 7°C for samples) [ [17]].

Ligand Immobilization

- Inject the diluted biotinylated ligand solution over one or more flow cells of the SA chip at a constant flow rate (e.g., 10-60 µL/min) until a sufficient immobilization level is achieved (~20 µg/ml recommended) [ [19] [17]].

- Designate one flow cell as a "reference cell" without ligand immobilization for background subtraction.

Analyte Binding and Kinetics Measurement

- Initiate a new run sequence with the flow rate set (e.g., 60 µL/min) [ [19]].

- Inject a "blank control" (RB only) over both the ligand and reference cells; this signal will be subtracted during analysis [ [17]].

- Sequentially inject a series of analyte concentrations (e.g., 0.63, 2.50, 5, 10, 15, 25 nM) over the ligand and reference surfaces [ [19]].

- For each injection, monitor the association phase in real-time. After a defined period, switch back to RB to monitor the dissociation phase.

- Follow each analyte injection with a regeneration solution (e.g., 20 mM NaOH) to remove the bound analyte and prepare the surface for the next cycle [ [19]].

Data Analysis

- Subtract the signal from the reference cell from the ligand cell data to account for bulk refractive index changes and non-specific binding.

- Fit the resulting background-subtracted sensograms to a suitable interaction model (e.g., a 1:1 binding model) using the instrument's software to determine the kinetic rate constants (ka, kd) and the equilibrium dissociation constant (KD) [ [19]].

The workflow for this protocol is summarized in the following diagram:

Protocol for High-Sensitivity Cancer Cell Detection Using an Advanced SPR Configuration

This protocol describes a numerical/experimental setup for a high-sensitivity SPR biosensor designed for cancerous cell detection, incorporating 2D materials to enhance performance [ [18]].

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Materials for High-Sensitivity SPR Sensor

| Item | Function / Description |

|---|---|

| Prism | BK7 prism for coupling light into the multi-layered sensor structure [ [18]]. |

| Sensor Layers | Ag (silver) as the plasmonic metal, ZnO and Si3N4 as dielectric adhesion/enhancement layers [ [18]]. |

| 2D Material | WS2 (Tungsten Disulfide) or other TMDCs (e.g., MoS2, MoSe2, WSe2) to enhance the electric field and light absorption capacity [ [18]]. |

| Sensing Medium | A solution containing the target cancerous cells (e.g., Jurkat for blood cancer, HeLa for cervical cancer) [ [18]]. |

| Simulation Software | Finite Element Method (FEM) simulation platform (e.g., COMSOL Multiphysics) for design and analysis [ [18]]. |

Step-by-Step Methodology

Sensor Fabrication and Setup

Baseline Measurement

- Introduce a control solution (e.g., buffer or medium with healthy cells) to the sensing medium.

- Scan the incident angle of light to determine the initial resonance angle (θres) for the baseline condition.

Sample Measurement and Sensitivity Calculation

- Replace the control solution with the sample containing the target cancerous cells.

- Re-scan the incident angle to determine the new resonance angle (θres + Δθ).

- Calculate the sensor's sensitivity (S) using the formula: S = Δθ / Δn, where Δn is the change in the refractive index caused by cell binding, expressed in degrees per Refractive Index Unit (deg/RIU) [ [18]].

- Analyze the electric field distribution across the sensor interfaces using FEM simulations to confirm performance enhancement [ [18]].

The following diagram illustrates the sensor's architecture and the critical resonance angle shift:

Data Interpretation and Analysis

The primary data output from an SPR experiment is a sensogram, which plots the response (e.g., in Resonance Units, RU) against time [ [17]]. The following diagram deconstructs a typical sensogram and links its phases to the key measurable outputs and derived parameters:

Case Study: Protein-Peptide Interaction

In the featured study of human α-thrombin binding to a biotinylated peptide (T10-39), the analysis of the sensograms using a 1:1 kinetic model yielded the following quantitative results [ [19]]:

- Association rate constant (ka): 3.5 × 106 M-1s-1

- Dissociation rate constant (kd): 3.9 × 10-2 s-1

- Equilibrium dissociation constant (KD): 10.9 nM

This KD value in the nanomolar range indicates a high-affinity interaction, which is consistent with the functional role of thrombin inhibitors [ [19]].

Case Study: Cancerous Cell Detection

For the advanced SPR biosensor configuration (BK7/ZnO/Ag/Si3N4/WS2), the key output was the resonance angle shift, which was used to calculate a sensitivity of 342.14 deg/RIU for detecting blood cancer (Jurkat) cells versus healthy cells [ [18]]. This high level of sensitivity, coupled with a high Figure of Merit (FOM=124.86 RIU-1), demonstrates the significant performance enhancement achievable through strategic material selection and sensor design [ [18]].

Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR) is a powerful, label-free physical process widely used for real-time biomolecular interaction analysis, chemical sensing, and medical diagnostics [20]. It occurs when plane-polarized light interacts with a thin metal film under conditions of total internal reflection, exciting a charge-density wave known as a surface plasmon at the metal-dielectric interface [21]. The resonance condition is exquisitely sensitive to changes in the refractive index near the metal surface, making SPR invaluable for detecting binding events and chemical interactions [21] [20].

This Application Note examines three critical dependencies that govern SPR phenomenon and its application in sensing: metal film properties, light polarization, and refractive index. We provide detailed protocols for leveraging these dependencies, with a specific focus on hydrogen gas detection using a palladium-coated aluminum grating, demonstrating practical implementation of these fundamental principles.

Theoretical Background

Fundamentals of Surface Plasmon Resonance

SPR occurs when the momentum of incident photons matches that of surface plasmons at a metal-dielectric interface [21]. In the most common Kretschmann configuration, a light beam undergoes total internal reflection at the interface of a high-index prism coated with a thin metal film, typically gold [21] [22]. Although no light propagates through the prism interface under total internal reflection conditions, an evanescent electrical field extends approximately a quarter wavelength beyond the reflecting surface [21]. When this evanescent wave couples energy to create surface plasmons in the metal film, a characteristic dip in reflected light intensity is observed at the resonance angle [21] [22].

The SPR condition is highly sensitive to changes in the refractive index of the medium adjacent to the metal film, with changes on the order of 10⁻⁵ refractive index units (RIU) readily detectable [23]. This sensitivity enables SPR applications in gas detection, biochemical sensing, and biomolecular interaction analysis [24] [20].

Critical Dependencies in SPR Systems

Table 1: Critical Dependencies in SPR Systems

| Dependency Category | Key Parameters | Impact on SPR Performance |

|---|---|---|

| Metal Film Properties | Material, thickness (optimal ~50 nm), porosity, morphology [21] [25] | Determines resonance sharpness, sensitivity, and signal strength [21] |

| Light Polarization | P-polarization (essential), polarization state changes in conical mounting [24] [21] | Enables SPR excitation; provides sensing signal via Stokes parameters [24] |

| Refractive Index | Sample refractive index, temperature sensitivity [21] [22] | Directly determines resonance angle/wavelength shift; core sensing mechanism [21] |

Materials and Equipment

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Materials for SPR Hydrogen Sensing Experiment

| Material/Reagent | Specifications | Function/Purpose |

|---|---|---|

| Aluminum Grating | UV holographic, 2400 lines/mm, shallow groove depth [24] | SPR coupler; provides momentum matching for plasmon excitation [24] |

| Palladium Target | High purity (for PLD) [24] | Hydrogen-sensitive transducer; changes complex refractive index upon H₂ exposure [24] |

| Hydrogen Gas Mixtures | 1-4% H₂ in N₂ (by volume) [24] | Analytic samples; concentrations near lower explosion level [24] |

| Laser Source | Wavelength: 672 nm, p-polarized [24] | SPR excitation source; monochromatic and polarized per requirements [21] |

| Pulsed Laser Deposition System | Nd-YAG, λ=266 nm, pulse width <2 ns [24] | Pd thin-film deposition with controlled thickness (~50 nm) [24] |

Instrumentation Setup

The experimental setup for SPR-based hydrogen detection requires precise optical configuration. A monochromatic laser source (672 nm) with p-polarization is directed toward the Pd-coated aluminum grating mounted on a goniometric stage for precise angular control [24]. The detection system must include a polarimetry setup capable of measuring the normalized Stokes parameter (s_3), which represents the intensity difference between right- and left-circularly polarized components of the reflected light [24] [23]. Temperature stabilization is essential as refractive index is temperature-sensitive [21].

Diagram 1: SPR Experimental Setup

Protocols

Fabrication of Pd Thin-Film Coated Aluminum Grating

Objective: Prepare a hydrogen-sensitive SPR substrate by depositing a palladium thin film on an aluminum diffraction grating.

Materials: UV holographic aluminum grating (2400 lines/mm), palladium target for PLD, acetone, isopropanol, nitrogen gas for drying.

Procedure:

- Substrate Cleaning: Clean the aluminum grating sequentially with acetone and isopropanol in an ultrasonic bath for 10 minutes each. Dry with nitrogen gas [24].

- Masking: Mask half of the grating surface to create both Pd-deposited and bare Al portions for comparative analysis [24].

- Laser Deposition: Place the grating in the PLD chamber with the Pd target. Evacuate the chamber to base pressure below 4 μTorr [24].

- Deposition Parameters:

- Laser wavelength: 266 nm

- Pulse energy density: 80 mJ/cm²

- Pulse repetition rate: 10 Hz

- Deposition rate: 15 Å/min

- Deposition time: 30 minutes (resulting in ~45 nm thickness) [24]

- Characterization: Verify Pd film uniformity using Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM) and Elemental Distribution with Energy Dispersive X-ray Spectroscopy (EDS) [24].

Troubleshooting Notes:

- Non-uniform Pd distribution may require optimization of PLD parameters.

- If SPR response is suboptimal, verify film thickness using profilometry and adjust deposition time accordingly.

Polarimetric SPR Measurement for Hydrogen Detection

Objective: Detect hydrogen gas concentrations of 1-4% in nitrogen by measuring changes in the Stokes parameter (s_3) resulting from SPR alterations.

Materials: Pd-coated aluminum grating from Protocol 4.1, hydrogen gas mixtures (1%, 2%, 3%, 4% H₂ in N₂), pure nitrogen gas, SPR instrument with conical mounting capability.

Procedure:

- Optical Alignment: Mount the Pd-coated grating in a conical configuration where the plane of incidence is not perpendicular to the grating grooves [24].

- Baseline Measurement: Illuminate the grating with p-polarized light at 672 nm wavelength. Flow pure nitrogen gas over the sensor surface and record the angular dependence of the Stokes parameter (s3) to determine the initial resonance angle (θ{sp}) [24].

- Hydrogen Exposure: Expose the sensor to hydrogen gas mixtures of increasing concentration (1-4% H₂ in N₂). For each concentration:

- Maintain constant gas flow rate (typically 100-200 mL/min)

- Allow sufficient time for signal stabilization (typically 2-5 minutes)

- Measure (s3) at fixed angle near (θ{sp}) [24]

- Data Collection: Record the changes in (s3) corresponding to each hydrogen concentration. Note that (s3) exhibits a rapid change around (θ_{sp}) with a steep slope, providing high sensitivity to small refractive index changes [24].

- Sensor Regeneration: Restore the sensor surface by flowing pure nitrogen to desorb hydrogen from the Pd film. Monitor (s_3) until it returns to baseline [24].

Troubleshooting Notes:

- If response is sluggish, check gas flow system for leaks or blockages.

- If signal drift occurs, ensure temperature stability as refractive index is temperature-sensitive [21].

- For incomplete regeneration, increase nitrogen flow rate or duration.

Data Analysis and Interpretation

Objective: Extract quantitative hydrogen concentration information from polarimetric SPR data.

Procedure:

- Resonance Angle Determination: Identify the zero-crossing point of the (s3) versus angle curve as the resonance angle (θ{sp}) [24] [23].

- Calibration Curve: Plot changes in (s_3) at fixed angle against hydrogen concentration to create a calibration curve.

- Response Time Calculation: Determine the time required for the (s_3) signal to reach 90% of its maximum value upon hydrogen exposure.

- Limit of Detection Estimation: Based on signal-to-noise ratio of (s_3) measurement, calculate the minimum detectable hydrogen concentration.

Diagram 2: Data Analysis Workflow

Results and Data Analysis

Performance Metrics

Table 3: Hydrogen Sensing Performance Using Polarimetric SPR

| Hydrogen Concentration | Change in s₃ | Response Time | Signal Stability |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1% in N₂ | Measurable detection [24] | Data not provided | Stable response [24] |

| 2% in N₂ | Significant change [24] | Data not provided | Stable response [24] |

| 3% in N₂ | Significant change [24] | Data not provided | Stable response [24] |

| 4% in N₂ | Maximum response [24] | Data not provided | Stable response [24] |

The experimental results demonstrate that the polarimetric SPR sensing technique using the normalized Stokes parameter (s3) successfully detects hydrogen gas concentrations from 1% to 4% in nitrogen, with stable and sensitive response [24]. The rapid change in (s3) around the resonance angle provides the sensitivity required for detecting small changes in the complex refractive index of the Pd thin film when exposed to hydrogen [24].

Discussion

The critical dependencies outlined in this Application Note highlight the interconnected relationship between metal film properties, light polarization, and refractive index in SPR systems. The Pd-coated aluminum grating in a conical mounting exploits all three dependencies: the Pd film serves as both SPR coupler and hydrogen transducer, the conical mounting enables polarization conversion, and the hydrogen-induced refractive index change produces measurable signals via altered polarization state [24].

This approach demonstrates particular advantage for hydrogen sensing near the lower explosion level (4%), where safety requirements necessitate sensitive and reliable detection [24]. The use of (s_3) as the detection parameter rather than traditional intensity measurements provides enhanced sensitivity to small refractive index changes, with demonstrated capability to detect changes on the order of 10⁻⁵ RIU [23].

The polarization-based SPR sensing methodology can be extended beyond hydrogen detection to other chemical and biological sensing applications where precise refractive index measurement is required. Recent advances in high-throughput SPR platforms further enhance the utility of these principles for drug discovery applications, enabling rapid screening of molecular interactions [26] [20].

This Application Note has detailed the critical dependencies of metal film properties, light polarization, and refractive index in Surface Plasmon Resonance systems, providing specific protocols for implementing these principles in hydrogen gas detection. The polarimetric approach using Stokes parameter (s_3) measurement in a conical mounting configuration provides sensitive and stable detection of hydrogen concentrations relevant to industrial safety applications.

The principles and methodologies described herein can be adapted to various SPR sensing applications in drug discovery, environmental monitoring, and clinical diagnostics, providing researchers with a framework for leveraging the fundamental dependencies that govern SPR phenomena.

SPR in Action: Cutting-Edge Applications from the Lab to the Clinic

Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR) has established itself as a cornerstone technology in biophysical analysis for drug discovery, providing real-time, label-free detection of molecular interactions. Its unique capacity to quantify binding kinetics (association rate k_on, dissociation rate k_off) and equilibrium affinity (K_D) makes it indispensable for characterizing therapeutic candidates, from small molecules to biologics [27]. Within the context of a broader thesis on SPR applications, this document details advanced protocols for kinetic profiling and fragment-based screening. These methodologies are critical for addressing key challenges in modern drug development, including the identification of promising fragment hits with weak affinities and the thorough characterization of lead compounds to minimize off-target effects and optimize binding properties [28] [27].

The application of SPR has expanded significantly into fragment-based drug discovery (FBDD), where it is valued for its low protein consumption and ability to detect weak, transient interactions that are typical of low molecular weight fragments [28]. Furthermore, innovative SPR platforms now enable more complex analyses, such as measuring the avidity of cell-antibody interactions, providing deeper insights into the functional behavior of biotherapeutics [29]. The following sections present structured experimental data, detailed protocols, and essential reagent information to guide researchers in implementing these powerful SPR techniques.

Data Presentation: Quantitative Kinetic and Affinity Profiling

The following tables consolidate key quantitative findings from recent SPR studies, highlighting affinity constants, kinetic rates, and structural determinants of binding.

Table 1: Affinity and Kinetic Profiling of Synthetic Cannabinoids at the CB1 Receptor via SPR

| Synthetic Cannabinoid | Core Structure | KD (M) | k_on (M⁻¹s⁻¹) | k_off (s⁻¹) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| JWH-018 | Indole | 4.35 × 10⁻⁵ | N/A | N/A |

| AMB-4en-PICA | Indole | 3.30 × 10⁻⁵ | N/A | N/A |

| FDU-PB-22 | Indole | 1.84 × 10⁻⁵ | N/A | N/A |

| MDMB-4en-PINACA | Indazole | 5.79 × 10⁻⁶ | N/A | N/A |

| 5F-AKB-48 | Indazole | 8.29 × 10⁻⁶ | N/A | N/A |

| FUB-AKB-48 | Indazole | 1.57 × 10⁻⁶ | N/A | N/A |

Key Findings from CB1 Receptor Studies:

- Core Structure Impact: Indazole-based SCs consistently demonstrated stronger CB1 receptor affinity (lower K_D) compared to their indole-based counterparts (unpaired t-test, p < 0.01) [30].

- Head Group Effect: Replacing a 5-fluoropentyl head group with a p-fluorophenyl head group enhanced receptor binding affinity. For example, FUB-AKB-48 (p-fluorophenyl) showed substantially stronger binding than 5F-AKB-48 (5-fluoropentyl) [30].

Table 2: Cell-Antibody Avidity Analysis via SPR Imaging (CellVysion Platform)

| Cell Line | Antibody/Target | Critical Ligand Density at Tipping Point (µRIU) | Shear Flow for Wash (µL/s) |

|---|---|---|---|

| LNCaP | Target A | Data from [29] | 80 (High Avidity) |

| NCI-H1792 | Target B | Data from [29] | 80 (High Avidity) |

| LCL (GM12882) | Target C | Data from [29] | 80 (High Avidity) |

| Red Blood Cells (RBCs) | FcγRIIa (Opsonized) | Data from [29] | 5 (Low Avidity) |

Key Findings from Avidity Studies:

- The "tipping point"—the specific ligand density at which cells remain bound under defined shear flow—serves as a quantitative metric for avidity and is characteristic of a specific antibody–cell line combination [29].

- The tipping point shifts with increasing shear force and reflects the combined influence of receptor density and monovalent affinity on the cellular level [29].

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Kinetic Profiling of Small Molecules against Immobilized GPCRs

This protocol is adapted from studies on Synthetic Cannabinoid (SC) binding to the CB1 receptor [30].

1. Sensor Chip Preparation:

- Immobilization Surface: Use a CM5 Series S sensor chip.

- Ligand: Purified CB1 receptor protein.

- Activation: Inject a 1:1 mixture of 0.4 M EDC (N-Ethyl-N'-(3-dimethylaminopropyl)carbodiimide) and 0.1 M NHS (N-hydroxysuccinimide) for 7 minutes to activate the carboxylated dextran matrix.

- Coupling: Dilute the CB1 receptor protein in 10 mM sodium acetate buffer (pH 4.5) and inject until an immobilization level of approximately 2500 Response Units (RU) is achieved.

- Blocking: Deactivate remaining esters with a 7-minute injection of 1 M ethanolamine-HCl (pH 8.5).

- Stabilization: Condition the surface with multiple short injections of the running buffer (e.g., HBS-EP+: 10 mM HEPES, 150 mM NaCl, 3 mM EDTA, 0.05% v/v Surfactant P20, pH 7.4) until a stable baseline is achieved.

2. analyte Binding Kinetics:

- Sample Preparation: Serially dilute small molecule analytes (e.g., synthetic cannabinoids) in running buffer. A typical concentration series may range from 0.1 to 100 µM.

- Data Collection: Inject analyte samples over the CB1-functionalized and reference flow cells at a constant flow rate of 30 µL/min for a 120-second association phase, followed by a 300-second dissociation phase with running buffer.

- Regeneration: Regenerate the surface with a 30-60 second pulse of 10 mM Glycine-HCl (pH 2.0) to remove bound analyte without denaturing the immobilized receptor.

3. Data Analysis:

- Reference and buffer subtraction must be performed to correct for bulk refractive index shifts and non-specific binding.

- Fit the processed sensorgrams to a 1:1 Langmuir binding model using the instrument's software (e.g., Biacore T200 Evaluation Software) to extract the kinetic rate constants (

k_on,k_off) and calculate the equilibrium dissociation constant (K_D = k_off / k_on).

Protocol 2: Fragment-Based Primary Screening using SPR

This protocol outlines a generic fragment screening campaign, as referenced in the literature [28] [31].

1. Library and Sample Preparation:

- Fragment Library: Utilize a curated library, such as a subset of the European Fragment Screening Library (EFSL). Fragments typically comply with the "Rule of Three" (MW < 300, cLogP ≤ 3, HBD ≤ 3, HBA ≤ 3) [31].

- Sample Preparation: Prepare fragment solutions at a high concentration (e.g., 0.2-1 mM) in running buffer containing a low percentage of DMSO (e.g., 1-2%). Maintain a consistent DMSO concentration across all samples and buffers to prevent artifacts.

2. Target Immobilization:

- Immobilize the purified protein target on a suitable sensor chip (e.g., CM5) via standard amine coupling or capture coupling (e.g., using His-tag/anti-His antibody systems) to a level of 5,000-15,000 RU.

3. Screening Cycle:

- Use a high-throughput capable SPR instrument.

- Inject each fragment in single-point format for 30-60 seconds at a high flow rate (e.g., 50 µL/min).

- Monitor both the association and dissociation phases briefly (e.g., 60-120 seconds each).

- Include a DMSO solvent correction cycle and positive/control injections throughout the screen for quality control.

4. Hit Identification and Validation:

- Identify hits as fragments producing a significant, concentration-dependent response relative to a negative control and the DMSO solvent correction.

- Validate primary hits by performing a full concentration series kinetic analysis (as in Protocol 1) to confirm binding and obtain kinetic parameters.

Protocol 3: Profiling Lectin-Glycan Binding Kinetics on Single Cells

This protocol is based on in-situ glycosylation profiling of single cells using SPR imaging [32].

1. Cell Preparation and Surface Immobilization:

- Culture adherent cells (e.g., HeLa) directly on a gold-coated, glass SPR imaging chip.

- Fix cells with 4% paraformaldehyde for 10 minutes at room temperature to preserve morphology and minimize internalization of probes.

- Wash the cell-coated chip with PBS buffer and mount it in the SPR imager flow cell.

2. Lectin Binding Kinetics:

- Probe Solutions: Prepare unlabeled lectins (e.g., WGA, SBA, ConA) in PBS at multiple concentrations (e.g., 10, 25, 50, 100 µg/mL).

- Association Phase: Inject lectin solutions over the cell surface at a constant flow rate of 150 µL/min for a sufficient time (e.g., 10-15 minutes) to observe binding.

- Dissociation Phase: Replace the lectin solution with PBS buffer and monitor the signal decay for an equal duration.

- Regeneration: Remove bound lectin by injecting a competitive sugar solution (e.g., 50 mM N-acetylglucosamine for WGA) for 30 seconds.

3. Data Analysis for Heterogeneous Binding:

- Extract binding curves (Response vs. Time) from regions of interest (ROIs) defined around individual cells.

- Fit the binding curves to a one-to-two binding model to account for lectin binding to two distinct glycan motifs, which provides a superior fit compared to the simple one-to-one model [32].

- The model will yield two sets of kinetic parameters (

k_on1,k_off1,K_D1;k_on2,k_off2,K_D2) for each lectin-cell interaction.

Signaling Pathways and Experimental Workflows

The following diagrams illustrate the core experimental workflow for SPR-based fragment screening and the key concept of avidity measurement, generated using DOT language.

SPR Fragment Screening Funnel

Cell-Antibody Avidity Measurement

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Reagents and Materials for SPR Experiments

| Reagent/Material | Function/Application | Example Specifications |

|---|---|---|

| CM5 Sensor Chip | A carboxymethylated dextran matrix covalently linked to a gold film; the standard surface for amine coupling of proteins. | (Cytiva) |

| HBS-EP+ Buffer | A standard running buffer for SPR; provides pH stabilization, ionic strength, and surfactant to minimize non-specific binding. | 10 mM HEPES, 150 mM NaCl, 3 mM EDTA, 0.05% P20 Surfactant, pH 7.4 |

| Amine Coupling Kit | Contains the reagents (NHS, EDC) for activating carboxyl groups on the sensor chip surface and ethanolamine-HCl for blocking. | (Cytiva) |

| Streptavidin Sensor Chip (e.g., SA) | Used for capturing biotinylated ligands (e.g., biotinylated antibodies, receptors), enabling a uniform orientation. | (Xantec Bioanalytics GmbH) |

| Pioneer F1/F2 Sensor Chips | Integrated fluidic and sensing components designed for high-throughput screening applications. | (Carterra) |

| Fragment Screening Library | A collection of 500-2000 low molecular weight compounds designed for high chemical diversity and optimal physicochemical properties. | E.g., European Fragment Screening Library (EFSL) [31] |

| HaloTag Fusion Protein System | Enables uniform, oriented capture of target proteins onto specially coated SPR chips or glass slides via the HaloTag protein. | (SPOC Proteomics) [27] |

Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR) technology has emerged as a powerful tool in clinical diagnostics and biomarker research, enabling real-time, label-free detection of molecular interactions. This optical sensing technique detects changes in the refractive index at a metal surface, allowing researchers to monitor binding events between biomolecules without the need for fluorescent or radioactive labels [33] [34]. The technology's versatility spans from detecting small molecule therapeutics to large biomolecular complexes, making it invaluable across diverse diagnostic applications including viral detection, cancer biomarker identification, and therapeutic drug monitoring [35] [36].

The significance of SPR in clinical diagnostics lies in its ability to provide quantitative data on binding affinity, kinetics, and concentration with high sensitivity and specificity. Unlike traditional detection methods that often require complex sample preparation and labeling, SPR offers real-time monitoring of biomolecular interactions, significantly reducing analysis time while providing rich kinetic information [6] [37]. This technical advantage positions SPR as a transformative technology for advancing personalized medicine through precise biomarker quantification and therapeutic monitoring.

Fundamentals of SPR Technology in Diagnostic Applications

Basic Principles and Detection Mechanism

SPR technology operates on the principle of detecting changes in the refractive index at the interface between a metal surface (typically gold) and a dielectric medium. When polarized light strikes the metal surface under total internal reflection conditions, it generates an evanescent wave that excites surface plasmons—collective oscillations of free electrons [5] [34]. This excitation results in a characteristic dip in the reflected light intensity at a specific angle known as the resonance angle [3].

The critical detection mechanism in SPR biosensing relies on the fact that the resonance angle is exquisitely sensitive to changes in refractive index within approximately 300 nanometers of the metal surface. When biomolecular binding events occur on the sensor surface, they alter the local refractive index, causing a measurable shift in the resonance angle [34]. This shift, quantified in resonance units (RU), is directly proportional to the mass concentration of bound material, with 1 RU representing approximately 1 pg/mm² of bound protein [33] [34]. The real-time monitoring of these binding events produces a sensorgram—a plot of response (RU) versus time—that visually represents the association, equilibrium, and dissociation phases of molecular interactions [34].

Advancements in SPR Sensing Platforms

Recent technological advancements have expanded SPR capabilities for clinical diagnostics. Traditional SPR platforms utilizing rigid glass substrates are now complemented by flexible sensors employing polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS) substrates, which maintain optical performance while accommodating complex deformation requirements [5]. The development of localized SPR (LSPR) has further enhanced detection capabilities, particularly for small molecule analytes [6].

High-throughput SPR systems with continuous flow microfluidics, such as Bruker's Sierra SPR-24/32 Pro with Hydrodynamic Isolation technology, enable simultaneous analysis of multiple interactions while minimizing sample consumption [3]. SPR imaging (SPRi) extends these capabilities further by allowing two-dimensional monitoring of array-based binding events, facilitating multiplexed detection of numerous biomarkers in a single experiment [3]. These technological innovations have significantly broadened the application scope of SPR in clinical settings where simultaneous detection of multiple disease markers is essential for comprehensive diagnostic profiling.

Quantitative Analysis of SPR Performance in Clinical Applications

The utility of SPR in clinical diagnostics is demonstrated through its performance metrics across various applications. The following table summarizes key analytical performance data for SPR-based detection of different analyte classes relevant to clinical diagnostics.

Table 1: Analytical Performance of SPR in Clinical Diagnostic Applications

| Analyte Class | Specific Target | Detection Range | Limit of Detection (LOD) | Sample Matrix | Reference Method Comparison |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Small Molecule Drugs | Chloramphenicol (CAP) | 0.1–50 ng/mL | 0.099 ± 0.023 ng/mL | Blood samples | Lower LOD than UPLC-UV [35] |

| Antibodies | Anti-ERBB2 (Trastuzumab) | N/A | Affinity constant: 1.45 nM | Buffer system | SPR kinetic analysis [33] |

| Peptides | Glutathione (GSH) | N/A | Optimal adsorption at pH 12 | Aqueous solution | Reflectivity measurements [5] |

| Flexible SPR Sensor | Sodium chloride solutions | General sensitivity: 3385.5 nm/RIU | N/A | Aqueous solution | Traditional glass substrate [5] |

The performance characteristics of SPR biosensors can be further illustrated through their methodological validation parameters. The following table summarizes key validation metrics for SPR in quantitative analysis of biological samples, demonstrating its reliability for clinical applications.

Table 2: Method Validation Parameters for SPR-Based Detection of Chloramphenicol in Blood Samples

| Validation Parameter | Performance Result | Acceptance Criteria | Clinical Relevance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Intra-day Accuracy | 98%–114% | Meets analytical requirements | Reliable for same-day clinical testing |

| Inter-day Accuracy | 110%–122% | Meets analytical requirements | Suitable for longitudinal therapeutic monitoring |

| Precision | Demonstrated | Meets analytical requirements | Consistent results across multiple measurements |

| Matrix Effect | Characterized | Acceptable for blood samples | Direct analysis of complex biological samples |

| Extraction Recovery Rate | Determined | Sufficient for quantification | Efficient analyte recovery from biological matrix |

Experimental Protocols for SPR-Based Biomarker Detection

Sensor Surface Preparation and Ligand Immobilization

Materials and Reagents:

- CM5 sensor chip (carboxymethylated dextran matrix) [33] [34]

- 1-ethyl-3-(3-dimethylaminopropyl) carbodiimide hydrochloride (EDC) and N-hydroxysuccinimide (NHS) for surface activation [35]

- Sodium acetate buffers (pH 4.0-5.5) for ligand dilution [35]

- Ethanolamine-HCl for blocking remaining active groups [35]

- Phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) or HBS-EP buffer as running buffer [35] [33]

- Purified ligand (antibody, protein, or nucleic acid aptamer)

Step-by-Step Procedure:

- System Priming: Prime the SPR instrument with filtered and degassed running buffer according to manufacturer specifications [36].

- Sensor Chip Activation: Inject a mixture of EDC and NHS (typically 1:1 ratio) over the sensor surface for 7-10 minutes to activate carboxyl groups on the dextran matrix [35] [33].

- Ligand Immobilization: Dilute the ligand in appropriate immobilization buffer (e.g., 10 mM sodium acetate, pH 4.0-5.5) and inject over the activated surface for sufficient time to achieve desired immobilization level [35]. The optimal pH should be determined empirically through preliminary tests at different pH values [34].

- Surface Blocking: Inject ethanolamine-HCl (typically 1 M, pH 8.5) for 5-7 minutes to block remaining activated ester groups [35].

- Surface Stability Check: Monitor the baseline stability in running buffer until a stable signal is achieved (typically 5-10 minutes) [33].

Biomarker Binding Analysis and Kinetic Characterization

Materials and Reagents:

- Purified analyte (biomarker of interest) in serial dilutions

- Running buffer (identical to immobilization step)

- Regeneration solution (e.g., 10 mM glycine-HCl, pH 2.0-3.0)

Step-by-Step Procedure:

- Sample Preparation: Prepare analyte dilutions in running buffer spanning a concentration range of 10× below to 10× above the expected KD [37]. Include a zero concentration (blank) for reference subtraction.

- Binding Assay: Inject analyte samples over the ligand surface using a flow rate of 30 μL/min for 120-180 seconds association phase, followed by dissociation phase in running buffer for 300-600 seconds [35].

- Surface Regeneration: Apply a regeneration solution (e.g., 10 mM glycine-HCl, pH 2.0) for 30-60 seconds to remove bound analyte without damaging the immobilized ligand [33].

- Data Collection: Repeat steps 2-3 for all analyte concentrations in ascending order, with duplicate injections for statistical reliability [33].

- Reference Subtraction: Subtract signals from reference flow cell (without ligand) and blank injections to account for bulk refractive index changes and non-specific binding [36].

Data Analysis and Interpretation

- Sensorgram Processing: Align sensorgrams to baseline and zero on the time axis at the start of injection [36].

- Kinetic Analysis: Fit processed sensorgrams to appropriate binding models (e.g., 1:1 Langmuir binding) using software such as BIAevaluation or Scrubber-2 to calculate association rate (kₐ), dissociation rate (kḍ), and equilibrium dissociation constant (K_D = kḍ/kₐ) [36] [37].

- Affinity Determination: For steady-state analysis, plot response at equilibrium against analyte concentration and fit to a saturation binding model to determine K_D [37].

- Quality Assessment: Evaluate fitting quality through residual analysis and chi-squared values to ensure appropriate model selection [36].

Diagram 1: SPR Experimental Workflow for Biomarker Detection

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Successful implementation of SPR-based biomarker detection requires careful selection of appropriate reagents and materials. The following table outlines key components essential for developing robust SPR assays in clinical diagnostics.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for SPR-Based Biomarker Detection

| Reagent/Material | Function/Application | Examples/Specifications | Considerations for Clinical Samples |

|---|---|---|---|

| CM5 Sensor Chip | Standard carboxymethylated dextran matrix for ligand immobilization | Excellent chemical stability; suitable for most applications [33] [34] | Compatible with various coupling chemistries; minimal non-specific binding |

| SA Sensor Chip | Pre-immobilized streptavidin for capturing biotinylated ligands | Ideal for nucleic acid aptamers, biotinylated antibodies [34] | Strong biotin-streptavidin interaction (KD ~10⁻¹⁵ M) withstands regeneration |

| NTA Sensor Chip | Nitrilotriacetic acid for immobilizing His-tagged proteins | Controlled orientation via metal chelation [34] | Requires Ni²⁺ or other divalent cations; moderate stability during regeneration |

| EDC/NHS | Crosslinkers for activating carboxyl groups on sensor surface | Forms reactive esters for covalent coupling to primary amines [35] [33] | Fresh preparation required; optimal pH 4.5-5.0 for efficient activation |

| HBS-EP Buffer | Standard running buffer with surfactant | 10 mM HEPES, 150 mM NaCl, 3 mM EDTA, 0.05% surfactant P20 [35] | Reduces non-specific binding; compatible with most biomolecular interactions |

| Glycine-HCl | Regeneration solution for removing bound analyte | Typically 10-100 mM, pH 2.0-3.0 [33] | Must be optimized for each ligand-analyte pair to maintain ligand activity |

Troubleshooting Common Challenges in SPR-Based Detection

Despite its powerful capabilities, SPR implementation in clinical diagnostics presents several technical challenges that require systematic troubleshooting approaches.

Non-Specific Binding and Signal Artifacts

Non-specific binding (NSB) represents a significant challenge in SPR analysis of complex clinical samples such as blood, plasma, or tissue extracts. NSB occurs when analytes or matrix components interact with the sensor surface through mechanisms other than the specific ligand-analyte interaction of interest [33]. To minimize NSB:

- Incorporate additives such as surfactants (e.g., Tween 20), bovine serum albumin (BSA), dextran, or polyethylene glycol (PEG) in the running buffer [33]

- Include a reference flow cell with immobilized non-reactive ligand or blocked surface without specific ligand [33]

- Consider alternative sensor chips with lower charge (e.g., CM4) for highly basic proteins that may exhibit electrostatic interactions with the dextran matrix [34]

- Optimize pH and ionic strength of running buffer to minimize non-specific electrostatic interactions

Regeneration Optimization and Surface Stability

Regeneration is the process of removing bound analyte while maintaining ligand activity for repeated binding cycles. Ineffective regeneration leads to signal drift and inaccurate kinetic measurements [33]. Effective regeneration strategies include:

- Systematic screening of regeneration solutions including acidic (10-100 mM glycine-HCl, pH 2.0-3.0), basic (10-50 mM NaOH), high salt (1-2 M NaCl), or specific chaotropes [33]

- Testing regeneration contact time (typically 15-60 seconds) and monitoring baseline stability after multiple regeneration cycles

- Adding 10% glycerol to regeneration solutions to enhance ligand stability [33]

- For difficult regeneration conditions, consider capture-based immobilization strategies that allow periodic surface renewal

Mass Transport Limitation and Data Quality

Mass transport limitation occurs when the rate of analyte diffusion to the sensor surface is slower than the association rate, leading to underestimated association rate constants [34]. This problem can be identified and addressed through:

- Performing experiments at multiple flow rates (e.g., 10, 30, and 50 μL/min); consistent kinetic parameters across flow rates indicate minimal mass transport effects [34]

- Reducing ligand density to minimize rebinding effects during dissociation phase

- Using sensor chips with shorter dextran matrices (e.g., CM3) or flat surfaces (C1) to improve mass transfer for large analytes [34]

SPR technology has established itself as a versatile and powerful platform for biomarker detection and clinical diagnostics, offering unique capabilities for real-time, label-free analysis of molecular interactions. The continuous advancement of SPR platforms, including the development of flexible substrates, high-throughput systems, and improved detection methodologies, continues to expand its applications in viral detection, cancer diagnostics, and therapeutic monitoring [35] [6] [5].

The implementation of robust experimental protocols, appropriate reagent selection, and systematic troubleshooting approaches enables researchers to overcome common challenges associated with SPR-based detection in complex clinical samples. As SPR technology evolves toward greater sensitivity, miniaturization, and multiplexing capabilities, its role in advancing personalized medicine and precision diagnostics is poised to grow significantly, providing researchers and clinicians with powerful tools for understanding disease mechanisms and developing targeted therapeutic interventions.

Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR) technology has emerged as a powerful analytical tool for real-time, label-free detection of molecular interactions, offering significant advantages for food safety and environmental monitoring. This technique enables researchers to detect minute quantities of pollutants and contaminants with remarkable precision and sensitivity, addressing critical challenges in global public health. The dynamic interplay between increasing chemical use in agriculture, industrial pollution, and foodborne health risks necessitates advanced detection methodologies that surpass traditional analytical techniques in speed, sensitivity, and practicality [38] [39]. SPR biosensors fulfill this need through their capacity for rapid, specific detection of diverse contaminants including pesticides, mycotoxins, heavy metals, and pathogenic microorganisms, making them invaluable for researchers and drug development professionals seeking to mitigate public health risks associated with contaminated food and environments [6] [40].

The fundamental principle of SPR technology involves monitoring changes in the refractive index at the interface between a metal film (typically gold) and a dielectric medium, which occurs when target analytes bind to recognition elements immobilized on the sensor surface. This interaction generates a measurable signal proportional to the mass concentration of the bound analyte, enabling real-time monitoring of binding events without requiring labels [41] [42]. Recent advancements in SPR biosensing have incorporated innovative materials including two-dimensional nanomaterials and transition metal dichalcogenides, significantly enhancing sensitivity and detection capabilities for trace-level contaminants [41]. The technology's versatility permits applications across diverse domains, from monitoring chemical contaminants in food supplies to detecting pathogenic microorganisms in environmental samples, establishing SPR as a cornerstone technology for safeguarding public health.

Theoretical Background and Technology Fundamentals

Principles of Surface Plasmon Resonance

Surface Plasmon Resonance operates on the principle of energy transfer between incident light and surface plasmons—collective oscillations of free electrons at a metal-dielectric interface. In conventional Kretschmann configuration, which is predominantly used in biosensing applications, a thin metal film (typically gold or silver) is deposited on a glass prism. When polarized light strikes this interface under total internal reflection conditions at a specific angle (the resonance angle), it generates an evanescent wave that penetrates the metal film and excites surface plasmons [41]. This energy transfer results in a measurable reduction in the intensity of reflected light at a specific incident angle. The resonance angle is exquisitely sensitive to changes in the refractive index within the evanescent field region, typically extending 100-300 nanometers from the metal surface [6]. When target analyte molecules bind to recognition elements immobilized on the sensor surface, the local refractive index changes, producing a shift in the resonance angle that can be monitored in real-time, enabling label-free detection of molecular interactions.

The performance of SPR biosensors is quantified through several key parameters. Sensitivity, perhaps the most critical characteristic, refers to the magnitude of resonance shift per unit change in refractive index, typically expressed in degrees per refractive index unit (deg/RIU) [41]. The quality factor represents a combined measure of sensitivity and resonance curve sharpness, influencing the sensor's ability to detect minute changes in target analyte concentration. Detection accuracy relates to the precision in determining the resonance dip position, while the limit of detection (LOD) defines the smallest measurable analyte concentration [41]. Contemporary SPR configurations achieve remarkable performance metrics, with recent demonstrations of heterostructure-based sensors reaching sensitivities of 234 deg/RIU, quality factors of 390 RIU⁻¹, and limits of detection as low as 4.26 × 10⁻⁶ RIU [41].

Advanced SPR Configurations and Material Innovations

Recent advancements in SPR technology have focused on enhancing performance through material innovations and heterostructure designs. Conventional SPR sensors utilizing single metal layers face limitations in sensitivity and detection capabilities. The incorporation of two-dimensional nanomaterials and transition metal dichalcogenides (TMDCs) has substantially advanced the field by enhancing the electric field at the sensing interface and improving biomolecule adsorption capabilities [41]. These materials exhibit exceptional optical and electrical properties, including tunable bandgaps, strong quantum confinement effects, and high charge transfer mobility, making them ideal for sensing applications.

Table 1: Advanced Materials for SPR Sensing Platforms

| Material Category | Representative Materials | Key Properties | Impact on Sensor Performance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Plasmonic Metals | Gold (Au), Silver (Ag) | Au: Chemical stability (0.13774 + 3.6183i RI) [41]; Ag: Higher sensitivity but prone to oxidation | Form the foundation for surface plasmon excitation |

| TMDCs | PtSe₂, WS₂, MoS₂ | PtSe₂: Tunable bandgap (1.2 eV monolayer), low toxicity, chemical stability (2.9189 + 0.9593i RI) [41] | Enhance charge transfer, increase adsorption area, improve stability |

| 2D Nanomaterials | Blue Phosphorene (BlueP), Graphene | BlueP/WS₂ heterostructure (2.48 + 0.17i RI) [41]; Large surface area, high electron mobility | Prevent oxidation in hybrid structures, enhance signal amplification |

| Hybrid Structures | BlueP/WS₂, PtSe₂-BlueP/WS₂ | Combine advantages of constituent materials, synergistic effects | Achieve superior sensitivity (234 deg/RIU), quality factor (390 RIU⁻¹) [41] |