Surface Science in Catalysis: From Atomic Design to Biomedical Applications

This article explores the transformative role of surface science in advancing modern catalysis, with a special focus on implications for biomedical and pharmaceutical research.

Surface Science in Catalysis: From Atomic Design to Biomedical Applications

Abstract

This article explores the transformative role of surface science in advancing modern catalysis, with a special focus on implications for biomedical and pharmaceutical research. It delves into foundational concepts like active sites and phase boundaries, examines cutting-edge characterization techniques such as scanning electrochemical microscopy, and discusses optimization strategies for single-atom and dynamic catalysts. By synthesizing insights from recent studies and conferences, the content provides a comprehensive framework for researchers and drug development professionals to understand and leverage surface-level phenomena for designing more efficient, selective, and stable catalytic processes, ultimately accelerating drug discovery and sustainable synthesis.

The Atomic Landscape: Uncovering Fundamental Principles of Surface Catalysis

In heterogeneous catalysis, the active site is not a passive spectator but the central communicative interface where critical molecular conversations occur. These nanoscale structures on catalyst surfaces serve as the definitive "seats" where reactant molecules adsorb, undergo transformation, and subsequently desorb as products. Within the broader thesis of applying surface science to catalysis research, understanding active sites transcends mere characterization—it requires a fundamental exploration of how their atomic arrangement, electronic properties, and local environment dictate catalytic efficiency and selectivity. Contemporary research leverages advanced spectroscopic and computational techniques to probe these sites under realistic working conditions, moving beyond idealized models to genuine structure-function relationships [1]. This application note details the experimental and data-centric approaches essential for characterizing, benchmarking, and understanding active sites, providing actionable methodologies for researchers dedicated to advancing catalytic science.

Quantitative Benchmarking of Catalytic Performance

The Critical Need for Standardized Benchmarking

A fundamental challenge in catalysis research is the objective comparison of catalytic activity across different materials and studies. The development of reliable benchmarks is paramount for contextualizing new catalyst performance against established standards. A meaningful benchmark requires well-characterized, readily available catalysts and agreed-upon reaction conditions that ensure measured turnover rates are free from artifacts such as catalyst deactivation or heat and mass transfer limitations [2]. Historically, attempts at standardization through reference materials like EuroPt-1 or World Gold Council catalysts were hindered by the lack of standardized measurement protocols [2].

CatTestHub: A Modern Database for Experimental Benchmarking

The CatTestHub database addresses this gap by serving as an open-access, community-wide platform for benchmarking experimental heterogeneous catalysis [2]. Its design is informed by the FAIR principles (Findability, Accessibility, Interoperability, and Reuse), structuring data to include intrinsic reaction rates, detailed reaction conditions, catalyst structural characterization, and reactor configurations [2]. This comprehensive approach allows researchers to rigorously compare their results against a validated, growing body of community data.

Table 1: Benchmark Catalysts and Model Reactions in CatTestHub

| Catalyst Class | Benchmark Chemistry | Key Measured Observables | Purpose of Benchmark |

|---|---|---|---|

| Metal Catalysts | Methanol Decomposition | Turnover Frequency (TOF), Activation Energy | Evaluation of metal site activity and stability [2]. |

| Metal Catalysts | Formic Acid Decomposition | Turnover Frequency (TOF), Selectivity | Assessment of dehydrogenation activity and probing of acid-base properties [2]. |

| Solid Acid Catalysts | Hofmann Elimination of Alkylamines | Rate of alkene formation, Site-time-yield | Quantification of Brønsted acid site density and strength [2]. |

Experimental Protocols for Active Site Characterization and Kinetic Analysis

Protocol: Measuring Intrinsic Kinetics on Catalyst Particles

The accurate determination of intrinsic reaction kinetics is a prerequisite for any meaningful discussion of active site communication. The following protocol outlines the critical steps, emphasizing the elimination of transport limitations to isolate the true chemical rate at the active sites [3].

Objective: To obtain the intrinsic kinetic parameters of a catalytic reaction, free from heat and mass transfer limitations.

Materials:

- Catalyst powder (synthesized or commercial)

- Tubular reactor system (packed-bed or plug-flow type)

- Mass Flow Controllers (MFCs) for gases

- Liquid feed syringe pump (if applicable)

- Online Gas Chromatograph (GC) or other analytical instrument

- Thermostat or oven for temperature control

Procedure:

- Catalyst Preparation and Loading:

- Sieve the catalyst powder to obtain a fraction with a particle diameter (Dp) typically less than 250 μm to minimize intraparticle diffusion limitations.

- Dilute the catalyst bed with an inert material (e.g., silicon carbide, quartz sand) of a similar particle size to ensure isothermal operation along the reactor axis.

- Load the diluted catalyst into the reactor tube to create a fixed bed with a small bed depth-to-diameter ratio to avoid axial dispersion.

Reactor System Checks:

- Perform leak checks on the entire gas flow system under pressurized conditions.

- Calibrate mass flow controllers and the syringe pump using appropriate methods (e.g., bubble flow meter for MFCs).

- Verify the calibration of all thermocouples, especially at the catalyst bed location.

Catalyst Pre-Treatment (Activation):

- Purge the system with an inert gas (e.g., N₂, Ar) at the desired reaction temperature.

- Activate the catalyst in-situ according to its specific requirements (e.g., reduction under H₂ flow, calcination in air).

Testing for Transport Limitations:

- Mass Transfer Control: At a fixed temperature and conversion, vary the catalyst mass while keeping the space-time (W/F) constant. If the reaction rate remains unchanged, interparticle mass transfer limitations are negligible.

- Kinetic Control: Perform experiments with at least two different catalyst particle sizes. If the observed reaction rate is independent of particle size, intraparticle diffusion limitations are absent.

- Thermal Control: Ensure the temperature profile across the catalyst bed is uniform. A small bed dilution and low conversion per pass help maintain isothermicity.

Kinetic Data Acquisition:

- Once transport limitations are ruled out, systematically vary reaction conditions (temperature, partial pressures of reactants) to collect kinetic data.

- Maintain differential reactor conditions (conversion typically <15%) to simplify data analysis and determine initial reaction rates directly.

- For each data point, allow the system to reach steady-state, confirmed by stable product composition over time, before recording measurements.

Data Analysis:

- Calculate turnover frequencies (TOF) where the number of active sites is known.

- Fit the initial rate data to various kinetic models (e.g., Power-law, Langmuir-Hinshelwood) to extract kinetic parameters like activation energy and reaction orders.

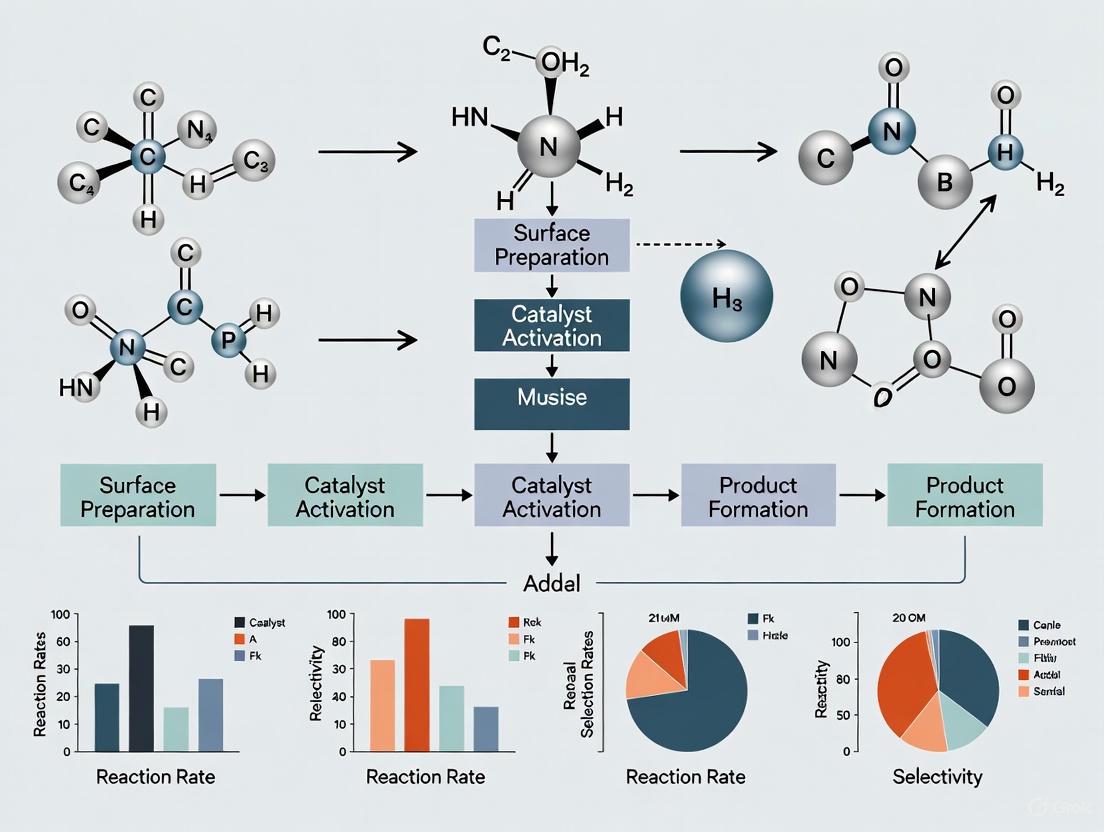

Workflow: From Catalyst Synthesis to Active Site Benchmarking

The following diagram illustrates the logical workflow for preparing a catalyst and systematically validating its performance, from initial synthesis to final benchmarking against community standards.

Diagram 1: Catalyst testing and benchmarking workflow.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

The reliable execution of catalytic experiments depends on the use of well-defined materials and reagents. The following table catalogues key items essential for research in this field, particularly for benchmarking studies.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for Catalytic Benchmarking

| Reagent/Material | Function & Purpose | Example from Benchmarking |

|---|---|---|

| Commercial Reference Catalysts (e.g., EuroPt-1, Zeolyst zeolites) | Provides a common, well-characterized material to enable direct comparison of experimental results between different research laboratories [2]. | Used as a baseline to validate new catalyst synthesis methods and experimental setups [2]. |

| Metal Precursors (e.g., Chlorides, Nitrates, Acetylacetonates) | The source of the active metal phase in catalyst synthesis. The anion can influence dispersion and final catalyst morphology. | In SAC synthesis, chlorides and nitrates of Fe are common precursors for Oxygen Reduction Reaction (ORR) catalysts [4]. |

| Porous Catalyst Supports (e.g., SiO₂, Al₂O₃, activated C, ZIF-8) | High-surface-area materials that stabilize and disperse active sites (e.g., metal nanoparticles, single atoms), preventing sintering. | ZIF-8 derived carbons are popular supports for SACs in ORR due to high surface area and tunable porosity [4]. |

| Probe Molecules (e.g., Methanol, Formic Acid, Alkylamines) | Simple, well-understood reactant molecules used to quantitatively probe the nature and density of specific active sites (metal, acid). | Methanol and formic acid decomposition are benchmark reactions for metal sites; Hofmann elimination of alkylamines probes Brønsted acid sites [2]. |

| Calibration Gases & Standards (e.g., 1% CO/He, 5% H₂/Ar, GC calibration mixes) | Essential for quantitative analysis of reaction products and for techniques like temperature-programmed desorption (TPD) and chemisorption. | Used to calibrate GCs and mass spectrometers for accurate measurement of reaction rates and active site counts. |

Advanced Topics: Protocol Standardization and Data-Driven Discovery

Standardizing Synthesis Protocols for Machine Readability

The lack of standardization in reporting synthesis protocols severely hampers automated text mining and collective data analysis—a significant bottleneck in a data-driven research era. A transformer model developed for extracting synthesis protocols for Single-Atom Catalysts (SACs) demonstrated a clear solution: when protocols were modified according to simple machine-readability guidelines, the model's performance in converting unstructured text into structured action sequences improved significantly [4]. Adopting such guidelines is crucial for creating large, structured databases that can accelerate catalyst discovery.

Operando and In Situ Characterization of Working Active Sites

Understanding active sites under realistic working conditions is a central goal of modern surface science in catalysis. The 2025 Gordon Research Conference on Chemical Reactions at Surfaces highlights the field's focus on "Structure-Function Relationships Under Thermal and Electrocatalytic Working Conditions" [1]. Key techniques driving this advance include:

- Operando X-ray Photoelectron Spectroscopy (XPS): Allows for the direct electronic and chemical analysis of catalyst surfaces during reaction conditions [1].

- Absorption Spectroscopy Under Reaction Conditions: Probes the local structure and oxidation state of active sites while the catalytic reaction is ongoing [1]. These operando approaches bridge the "materials gap" between idealized model systems and complex, real-world catalysts, providing unprecedented insight into the dynamic nature of active sites.

In catalytic science, a paradigm shift is underway, moving beyond the traditional view of stable, uniform catalyst surfaces to a new understanding that recognizes the unique properties of phase boundaries and metastable states. A phase boundary, in this context, refers to the spatial region where different structural or compositional domains of a catalyst meet—such as the interface between a metal and a support, the edge of a two-dimensional material, or the junction between different crystal facets. These regions often exist in a state of heightened energy, at the "edge of stability," where their structure is not permanently fixed but can dynamically respond to the reaction environment. Counter-intuitively, it is at this precarious edge, and not within the most stable, low-energy regions of the material, that optimal catalytic activity is frequently observed. This application note, framed within the broader thesis of surface science applications in catalysis research, details the underlying principles and provides practical methodologies for exploring and harnessing these dynamic interfaces. We synthesize insights from surface science, computational screening, and reactor engineering to provide researchers and development professionals with a framework for designing next-generation catalytic systems.

Theoretical Foundation: The Unique Properties of Edges and Interfaces

The high activity at phase boundaries and edges is not accidental but arises from distinct geometric and electronic structures that differ fundamentally from the bulk material or basal planes.

Geometric and Electronic Structure of Active Sites

At the geometric level, atoms located at edges, corners, and interfaces have lower coordination numbers compared to their counterparts on flat terraces. This under-coordination means these atoms have unsaturated "dangling" bonds, making them more prone to interact with and activate reactant molecules [5]. For example, in 2D materials like MoS2, the basal plane is often relatively inert, while the edge sites are highly active for reactions such as the hydrogen evolution reaction [5].

Electronically, this under-coordination leads to a rehybridization of orbitals and a shift in the local density of states (DOS). The d-band model, a cornerstone of surface science, provides a framework for understanding this, where shifts in the d-band center correlate with adsorption energies of key intermediates [6]. The full DOS pattern, including contributions from sp-bands, serves as a powerful descriptor for predicting catalytic performance, as materials with similar electronic structures tend to exhibit similar catalytic properties [6].

The Principle of Dynamic Instability

Operating at the "edge of stability" extends beyond static structural features. It also encompasses the strategic operation of catalytic reactors near their thermal stability limits. For strongly exothermic reactions, commercial multitubular fixed-bed reactors are often designed to operate just a few degrees from a "runaway" condition—a state of parametric sensitivity where small fluctuations in process parameters can lead to large, uncontrollable increases in temperature [7]. While hazardous if uncontrolled, operating near this thermodynamic boundary allows for maximized conversion and space-time yield. Advanced strategies, such as stacking catalyst beds with different activities along the reactor axis, can push this boundary further, enabling higher productivity while maintaining a safe operating margin [7]. This principle demonstrates that the optimal catalytic performance exists at the frontier of a system's stable operation.

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Protocol 1: High-Throughput Screening of Bimetallic Catalysts

This protocol describes a combined computational-experimental workflow for discovering bimetallic catalysts that can replace or reduce the use of platinum-group metals, using the similarity in electronic Density of States (DOS) as a primary descriptor [6].

Workflow Diagram:

Detailed Procedure:

Computational Screening Setup:

- Objective: Identify candidate bimetallic alloys to replace a reference catalyst (e.g., Pd).

- Descriptor Definition: The full electronic Density of States (DOS) pattern, including both d- and sp-states, is used as the primary descriptor. Similarity is quantified using the integrated difference of DOS patterns, weighted by a Gaussian function near the Fermi energy [6].

- Initial Pool: Consider a wide range of binary systems (e.g., 435 combinations from 30 transition metals).

High-Throughput DFT Calculations:

- For each binary system, calculate the formation energy (ΔEf) of multiple ordered crystal structures (e.g., B2, L10) to assess thermodynamic stability.

- Filter for structures with ΔEf < 0.1 eV/atom to ensure synthetic feasibility and resistance to phase separation under reaction conditions [6].

- For the thermodynamically stable candidates, compute the DOS projected onto the surface atoms of the most close-packed facet (e.g., (111) for fcc structures).

Candidate Selection:

- Calculate the DOS similarity value (ΔDOS) between each candidate and the reference catalyst.

- Prioritize candidates with the lowest ΔDOS values (e.g., < 2.0) for experimental validation [6].

Experimental Synthesis and Testing:

- Synthesize the top candidate alloys (e.g., via impregnation or co-precipitation) and form them into nanoparticles on a suitable support.

- Evaluate catalytic performance (e.g., for H₂O₂ synthesis: activity, selectivity, yield) under relevant conditions and compare directly to the reference catalyst.

- Validate the stability of the alloy structure post-reaction using techniques like XRD or TEM.

Protocol 2: Assessing Thermal Runaway in Stacked-Bed Reactors

This protocol outlines the procedure for constructing generalized runaway diagrams ("phase diagrams") for wall-cooled multitubular reactors with stacked catalyst activities, a key to operating safely at the edge of thermal stability [7].

Workflow Diagram:

Detailed Procedure:

System Definition:

- Reaction Kinetics: Obtain a reliable kinetic model for the reaction network, including main and side reactions.

- Reactor Parameters: Define reactor dimensions, coolant temperature, and operating pressure.

- Stacking Configuration: Specify the number of catalyst zones, their relative lengths, and their activity ratios (e.g., a low-activity catalyst in the initial zone followed by a high-activity catalyst).

Mathematical Modeling:

- Governing Equations: Develop a pseudo-homogeneous, one-dimensional model of the fixed-bed reactor. This includes mass and energy balance equations.

- Dimensionless Groups: Formulate key dimensionless groups, such as the Arrhenius number (γ), the Prater number (β), and a Damköhler number (Da), which govern the system's behavior [7].

Runaway Boundary Determination:

- Criterion: Use the occurrence of an inflection point in the temperature profile before the hot spot as the criterion for the onset of runaway.

- Parameter Mapping: Systematically vary the dimensionless parameters (e.g., Da, β) for a given stacked-bed configuration to find the exact combination where the runaway criterion is met.

Diagram Construction and Optimization:

- Plot the runaway boundaries for different stacking configurations on a Barkelew-type plot (e.g., β vs. Da).

- The resulting "phase diagram" will show regions of safe operation and runaway. The vertical shift of the runaway boundary compared to a uniform activity bed quantifies the stability improvement [7].

- Use this diagram to screen and optimize the catalyst activity profile (number of zones, activity ratios, zone lengths) for enhanced thermal stability and productivity.

Data Presentation and Analysis

Quantitative Data on Edge Sites and Catalytic Performance

Table 1: The Role of Edge Sites and Activity Stacking in Catalytic Performance

| Material / System | Key Structural Feature | Reaction | Performance Metric & Improvement | Reference / Cause |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| MoS₂ Nanosheets | Edge sites vs. basal plane | Hydrogen Evolution Reaction | Edges are active centers; basal plane is inert | [5] |

| Noble Metal NPs | Edges and corners | Various catalytic reactions | Higher activity due to lower coordination number of edge atoms | [5] |

| Ni₆₁Pt₃₉ Alloy | Similar DOS to Pd | H₂O₂ Direct Synthesis | 9.5-fold cost-normalized productivity vs. Pd | [6] |

| Stacked-Bed MTR | Two-zone catalyst activity | Fischer-Tropsch Synthesis | Conversion increased from 38% to 51% | [7] |

| Bimetallic Alloys | Electronic DOS similarity | Catalyst replacement | 4 of 8 computed candidates showed Pd-like performance | [6] |

Research Reagent Solutions and Essential Materials

Table 2: Key Reagents and Materials for Catalysis Research at Phase Boundaries

| Reagent / Material | Function / Application | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|

| Transition Metal Salts | Precursors for catalyst synthesis (e.g., Ni, Pt, Pd salts) | High purity to control alloy composition and minimize poisoning. |

| Supported Bimetallic Alloys | Model catalysts for high-throughput screening | Controlled stoichiometry and structure; validated by XRD/TEM. |

| Inert Diluent Particles | Modifying catalyst bed activity in fixed-bed reactors | Chemically inert (e.g., silica, alumina); matched particle size to control pressure drop. |

| Capping Agents | Controlling nanoparticle morphology during synthesis | Selective binding to specific crystal facets to promote edge site exposure. |

| Density Functional Theory (DFT) | High-throughput computational screening of catalysts | Predicts formation energy, electronic DOS, and adsorption energetics. |

The empirical and theoretical evidence consolidated in this application note firmly establishes that the most active sites for catalysis often reside at the physical and operational boundaries of stability. The under-coordinated atoms at material edges and interfaces, and the dynamically controlled state of reactors near thermal runaway, represent powerful paradigms for designing more active, selective, and efficient catalytic processes. The future of this field lies in the deeper integration of high-throughput computational screening, advanced in situ characterization, and sophisticated reactor engineering. This will allow researchers to not only discover new catalytic materials with optimized edge-site architectures but also to design dynamic reactor systems that can safely operate at their peak performance boundaries. By systematically exploring and exploiting these edges of stability, catalysis research can continue to drive innovations in energy conversion, chemical synthesis, and environmental remediation.

In surface science and heterogeneous catalysis, adsorbate coverage, denoted by the symbol θ, is a fundamental parameter defined as the fraction of an adsorbent's surface area that is occupied by adsorbate molecules [8]. It is a quantitative measure of how much of the available surface has been covered by the adsorbed species, ranging from θ = 0 (no adsorption, all sites free) to θ = 1 (complete monolayer coverage, all sites occupied) [9] [8]. The precise measurement and control of this parameter is critical for catalysis research, as the population of reactants, intermediates, and spectators on a catalyst surface directly governs the efficiency, selectivity, and mechanism of chemical transformations [10] [11].

The central role of adsorbate coverage stems from its direct influence on the accessibility of active sites. In catalytic cycles, reactants must first adsorb onto the catalyst surface before undergoing chemical transformation. As coverage increases, the available surface area for subsequent adsorption events decreases, thereby modulating reaction rates [9]. Furthermore, beyond simple site blocking, the local chemical environment and electronic structure of the catalyst can be altered by adsorbed species, leading to more complex cooperative or inhibitory effects that profoundly impact catalytic performance [12].

Theoretical Foundations and Adsorption Isotherms

The relationship between adsorbate coverage and the pressure (for gases) or concentration (for solutes) of the adsorbate in the bulk phase at a constant temperature is described mathematically by adsorption isotherms [13] [9]. These models provide a theoretical framework for predicting surface population under varying conditions and for extracting critical thermodynamic parameters.

Table 1: Key Adsorption Isotherm Models and Their Characteristics

| Isotherm Model | Fundamental Equation | Key Assumptions | Typical Application |

|---|---|---|---|

| Langmuir [13] [9] | ( \theta = \frac{KP}{1 + KP} ) | - Uniform surface sites- No adsorbate-adsorbate interactions- Monolayer coverage only | Chemisorption, homogeneous surfaces |

| Freundlich [13] | ( \frac{x}{m} = kP^{1/n} ) | - Empirical model- Heterogeneous surface- Heat of adsorption decreases with coverage | Physisorption, heterogeneous surfaces |

| BET [13] | ( \frac{x}{v(1-x)} = \frac{1}{v{mon}c} + \frac{x(c-1)}{v{mon}c} ) | - Multilayer adsorption possible- Langmuir assumptions apply to each layer | Physisorption, non-microporous surfaces |

The Langmuir isotherm, derived from kinetic principles, assumes a fixed number of identical, localized surface sites where adsorbed molecules do not interact [13] [9]. While these assumptions are often idealized and seldom all true in real systems, the Langmuir model remains a foundational tool in surface kinetics and thermodynamics due to its simplicity and wide applicability [13]. The Frumkin and Temkin isotherms represent more advanced models that incorporate a mean-field approximation for adsorbate-adsorbate interactions, which can either strengthen or weaken adsorption as coverage changes [11].

Diagram 1: The conceptual relationship between gas pressure, surface coverage via adsorption isotherms, and the resulting reaction kinetics. The model's predictions are governed by its underlying assumptions.

The Influence of Coverage on Reaction Pathways and Kinetics

Site Blocking and Lateral Interactions

At the most fundamental level, adsorbate coverage dictates reaction pathways through physical site blocking. As coverage increases, the number of free sites available for reactant adsorption decreases, which can directly lower the reaction rate [11]. However, the effects are often more nuanced due to lateral adsorbate-adsorbate interactions. These interactions, which can be either direct (through-space electrostatic) or indirect (substrate-mediated electronic couplings), alter the adsorption energies of neighboring species and the activation barriers for surface reactions [12]. For instance, the presence of spectator species like adsorbed furyl derivatives or solvent molecules (e.g., water, ethanol) can poison a metal catalyst surface by blocking sites critical for the desired reaction, thereby steering selectivity toward alternative pathways [10].

Modeling Coverage-Dependent Kinetics

To quantitatively describe how reaction rates depend on surface population, several kinetic models are employed. These models help distinguish the rate-controlling steps and the underlying mechanism of the adsorption process [14].

Table 2: Common Kinetic Models for Analyzing Adsorption Data

| Kinetic Model | Linear Form Equation | Parameters | Implied Mechanism |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pseudo-First-Order (PFO) [14] | ( \ln(qe - qt) = \ln qe - k1 t ) | k₁: Rate constant (min⁻¹)qₑ: Equilibrium capacity (mg/g) |

Physisorption, surface diffusion-controlled |

| Pseudo-Second-Order (PSO) [14] | ( \frac{t}{qt} = \frac{1}{k2 qe^2} + \frac{t}{qe} ) | k₂: Rate constant (g/mg/min)qₑ: Equilibrium capacity (mg/g) |

Chemisorption, electron sharing/exchange |

| Intraparticle Diffusion [14] | ( qt = k{id} t^{0.5} + C ) | k_id: Diffusion rate constant (mg/g/min⁰·⁵)C: Boundary layer thickness |

Intra-particle diffusion control |

The PSO model has been frequently observed to best explain sorption kinetics in many systems, indicating that the process is often governed by chemisorption, where the rate is influenced by the interaction of adsorption sites on the adsorbent surface with the adsorbate throughout the process [14].

Experimental Protocols and Measurement Techniques

Protocol 1: Quantifying Adsorbate Coverage via Active Particle Motion

This protocol exploits the phenomenon that the self-propelled motion of catalytic Janus particles is sensitive to surface poisoning, allowing for the quantification of adsorbate affinity and saturation coverage [10].

1. Reagent Preparation:

- Janus Particle Synthesis: Prepare a suspension of 1 µm carboxylate-modified polystyrene particles. Dilute to ~10⁻¹² M in anhydrous ethanol. Spin-coat 20 µL of this suspension onto clean glass cover slips at 2000 rpm to achieve a sub-monolayer of particles [10].

- Metal Deposition: Use electron beam physical vapor deposition to coat a 10 nm layer of Pt onto one hemisphere of the immobilized particles, creating the catalytic surface [10].

- Analyte Solutions: Prepare solutions of the adsorbate of interest (e.g., thioglycerol, furfural, ethanol) in the reaction medium, which is typically an aqueous solution of H₂O₂ (e.g., 10% v/v) [10].

2. Instrumentation and Data Acquisition:

- Imaging: Use an inverted optical microscope equipped with a high-speed camera (e.g., 20 fps) to track particle motion. Maintain a constant temperature using an environmental chamber if studying temperature dependence [10].

- Data Collection: Record videos of particle motion for at least 30 seconds per experimental condition. For each adsorbate, test a range of concentrations to construct a full isotherm [10].

3. Analysis and Fitting:

- Tracking: Use particle tracking software to determine the mean-squared displacement (MSD) and extract the active drift velocity (

v_active) of the particles. - Model Fitting: Normalize the velocity to that in pure H₂O₂ solution (

v_0). Fit the normalized velocity (v/v_0) versus adsorbate concentration ([A]) data to a site-blocking model to extract the half-inhibition constant (K_i) and the maximum surface coverage. The data can be fitted to:v/v_0 = 1 - θ, whereθ = (K_i [A]) / (1 + K_i [A])[10].

Protocol 2: Establishing Adsorption Isotherms and Thermodynamics

This general protocol outlines the steps for determining the adsorption equilibrium constant and related thermodynamic parameters.

1. Experimental Setup:

- Use a series of vials containing a fixed mass of adsorbent (e.g., 10-50 mg) and a fixed volume of the adsorbate solution.

- The initial concentration of the adsorbate should vary across the vials to generate a full isotherm [9].

2. Equilibrium Study:

- Agitate the vials in a temperature-controlled shaker until equilibrium is established (this must be determined by a preliminary kinetic study).

- Separate the adsorbent from the solution, typically by centrifugation or filtration.

- Analyze the supernatant to determine the equilibrium concentration (

C_e).

3. Data Processing:

- Calculate the amount adsorbed at equilibrium,

q_e (mg/g), using the mass balance equation:q_e = (C_o - C_e) * V / m, whereC_ois the initial concentration,Vis the solution volume, andmis the adsorbent mass. - Plot

q_eversusC_e(for liquids) or pressure (for gases). Fit the data to various isotherm models (Langmuir, Freundlich, etc.). The model with the highest regression coefficient (R²) and physical consistency is typically selected [13] [9] [14]. - To obtain the enthalpy of adsorption (

ΔH_ads), repeat the entire isotherm measurement at several different temperatures and apply the van't Hoff equation to the equilibrium constants [10].

Computational Modeling of Lateral Interactions

Modern computational approaches are indispensable for understanding coverage effects at the atomic level, where experimental measurement is challenging.

1. Cluster Expansion (CE) Methods: CE is a lattice-based model that parameterizes the energy of a system with a Hamiltonian that includes interaction terms for different clusters of adsorbates. Machine learning is used to fit these parameters to data from density functional theory (DFT) calculations. This approach is powerful for simulating systems with monatomic or diatomic species but can become intractable for complex reactions with many species [12].

2. Mean-Field Microkinetic Modeling (MKM): This method uses analytic relationships to describe how adsorption energies and reaction barriers change with the average surface coverage. While it does not explicitly consider spatial distributions of adsorbates, it is computationally efficient and can provide valuable insights into catalytic activity and selectivity trends [12].

3. Kinetic Monte Carlo (kMC) Simulations: kMC goes beyond the mean-field approximation by explicitly simulating stochastic events (adsorption, desorption, reaction) on a lattice representation of the surface. When parameterized with a CE Hamiltonian or other ML-based surrogate models, kMC can accurately predict macroscopic observables like turnover frequency from atomistic processes, explicitly accounting for lateral interactions and coverage effects [12].

Diagram 2: A workflow for computational modeling of adsorbate coverage on complex surfaces, highlighting the iterative process from first-principles calculations to predictive simulation.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Key Research Reagents and Materials for Adsorbate Coverage Studies

| Item | Typical Specification / Example | Primary Function in Experiment |

|---|---|---|

| Model Catalysts | Pt(111) single crystal, Pt/Silica nanoparticles | Well-defined surfaces for fundamental studies; high surface area materials for applied research. |

| Janus Particles | 1 µm polystyrene particles with 10 nm Pt cap [10] | Self-propelled probes for quantifying surface-adsorbate interactions under reaction conditions. |

| Strongly Interacting Adsorbate | Thioglycerol [10] | A model poison to validate techniques; forms strong bonds with metal surfaces, fully blocking sites. |

| Weakly/Intermediate Interacting Adsorbates | Furfural, Ethanol [10] | Model biomass-derived compounds or solvents to study competitive adsorption and site blocking. |

| Reaction Fuel / Oxidizer | Aqueous H₂O₂ (e.g., 10% v/v) [10] | Fuel for self-propelled motion of catalytic Janus particles; reactant in oxidation reactions. |

| Computational Codes | GPAW (DFT), ATAT (Cluster Expansion), kMC codes [11] [12] | Calculating adsorption energies, parameterizing interaction models, and simulating surface kinetics. |

Surface science provides the fundamental principles for understanding chemical reactions at the boundaries between phases, where catalytic transformations occur. Within this framework, single-atom catalysts (SACs) represent the ultimate frontier in precision engineering, isolating individual metal atoms on suitable supports to achieve unprecedented catalytic efficiency and specificity. These materials maximize atom utilization efficiency to nearly 100%, dramatically reducing metal loading while creating uniform active sites with distinct electronic properties that differ from their nanoparticle counterparts [15]. The emergence of SACs has fundamentally transformed catalyst design paradigms, enabling atomic-scale modulation of active sites to optimize reaction pathways for diverse applications ranging from environmental remediation to energy conversion [16].

The development of SACs exemplifies how surface science principles can be translated into practical catalytic technologies. By controlling the coordination environment of metal atoms at the single-atom level, researchers can precisely tailor reaction intermediates' adsorption energies and activation barriers [16]. This precision engineering approach has opened new possibilities for designing catalysts with specific functionality, moving beyond traditional trial-and-error methods toward rational design based on atomic-level understanding of surface processes.

Atomic-Scale Design Principles and Reaction Mechanisms

Structural Fundamentals of Single-Atom Catalysts

The unique properties of SACs originate from their specific structural characteristics, where isolated metal atoms are stabilized on support materials through heteroatom coordination or defect sites. Unlike nanoparticles, where metal atoms coordinate primarily with other metal atoms, single metal atoms in SACs experience strong interactions with their support, leading to distinctive electronic structures and catalytic behaviors [15]. The most common configuration features metal centers coordinated with nitrogen atoms embedded in carbon matrices (M-N-C), though recent advances have expanded to include other heteroatoms such as sulfur and oxygen, which further modulate electronic properties [16] [17].

The coordination environment profoundly influences catalytic performance by affecting the electronic structure of the metal center. For instance, introducing sulfur atoms into the coordination sphere of cobalt single atoms (SA Co-N/S) creates an electronic environment that significantly enhances activity for sulfur reduction reactions in sodium-sulfur batteries [17]. Similarly, engineering the first coordination sphere in SACs supported on BC3 monolayers can optimize performance for nitrate reduction reactions by balancing the number of valence electrons, nitrogen doping concentration, and specific coordination configurations [18].

Mechanistic Insights from Surface Science

Surface science techniques have revealed how SACs alter reaction pathways at the molecular level. In electrocatalytic CO₂ reduction, SACs exhibit distinctive product distributions compared to nanoparticle catalysts due to different intermediate binding energies [16]. The isolated nature of active sites in SACs prevents the formation of multi-metal site ensembles required for certain reaction pathways, thereby enhancing selectivity toward specific products. For CO₂ electroreduction, this often translates to improved carbon monoxide selectivity while suppressing competing hydrogen evolution reactions [16].

The mechanistic understanding of SAC functionality extends to environmental catalysis. In the selective catalytic reduction of NO by CO (CO-SCR), SACs enhance the adsorption and activation of NO through synergistic interactions with the support material [15]. This improved activation optimizes the reaction pathway, enabling efficient conversion of toxic NO and CO into harmless N₂ and CO₂ at lower temperatures than conventional catalysts.

Application Performance Metrics

Single-atom catalysts have demonstrated exceptional performance across diverse catalytic applications. The tables below summarize key metrics for environmental and energy applications.

Table 1: SAC Performance in Environmental Catalysis

| Catalyst | Reaction | Conditions | Temperature | Conversion/Selectivity | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ir₁/m-WO₃ | CO-SCR | 0.1% NO, 0.2% CO, 2% O₂ | 350°C | 73% NO conversion, 100% N₂ selectivity | [15] |

| 0.3Ag/m-WO₃ | CO-SCR | 0.1% NO, 0.4% CO, 1% O₂ | 250°C | ~73% NO conversion, 100% N₂ selectivity | [15] |

| Fe₁/CeO₂-Al₂O₃ | CO-SCR | 0.05% NO, 0.6% CO | 250°C | 100% NO conversion, 100% N₂ selectivity | [15] |

| Cu₁-MgAl₂O₄ | CO-SCR | 2.6% NO, 2.9% CO | 300°C | ~93% NO conversion, ~92% N₂ selectivity | [15] |

Table 2: SAC Performance in Energy Applications

| Application | Catalyst | Key Performance Metrics | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| CO₂ Electroreduction | Ni-N-C SAC | High CO Faradaic efficiency (>90%), low overpotential | [16] |

| CO₂ Electroreduction | Zn-N-C SAC | CO selectivity >90%, stable at industrial current densities | [16] |

| Na-S Batteries | SA Co-N/S | Enables complete sulfur transformation, high mass loading capability | [17] |

| Oxygen Reduction | Fe-N-C SAC | Comparable to Pt in alkaline media, superior stability | [16] |

Experimental Protocols for SAC Synthesis and Evaluation

SAC Synthesis Workflow

The following diagram illustrates the comprehensive workflow for developing and evaluating single-atom catalysts:

SAC Development Workflow

Protocol: Synthesis of M-N-C Single-Atom Catalysts

Objective: Prepare metal-nitrogen-carbon (M-N-C) single-atom catalysts with atomic dispersion of transition metal atoms (e.g., Fe, Co, Ni) on nitrogen-doped carbon supports.

Materials:

- Metal precursor (e.g., metal acetates, chlorides, or phthalocyanines)

- Nitrogen-rich carbon support (e.g., graphene oxide, carbon black, ZIF-8)

- Nitrogen precursor (if needed, e.g., dicyandiamide, urea, phenanthroline)

- Solvents (e.g., ethanol, deionized water)

Procedure:

- Impregnation: Dissolve metal precursor in suitable solvent (typically ethanol/water mixture) and mix with carbon support.

- Sonication: Sonicate the mixture for 60 minutes to ensure uniform dispersion.

- Stirring: Continuously stir for 12 hours at room temperature to facilitate adsorption.

- Drying: Remove solvent by rotary evaporation or oven drying at 60°C.

- Pyrolysis: Heat the sample under inert atmosphere (N₂ or Ar) with the following temperature program:

- Ramp from room temperature to 400°C at 5°C/min, hold for 2 hours

- Increase to target temperature (700-900°C) at 3°C/min, hold for 2 hours

- Cool naturally to room temperature under inert gas

- Acid Leaching (optional): Treat with 0.5M H₂SO₄ at 80°C for 8 hours to remove unstable nanoparticles.

- Washing and Drying: Rinse thoroughly with deionized water and dry at 60°C overnight.

Characterization Validation:

- Confirm atomic dispersion using aberration-corrected HAADF-STEM

- Analyze coordination environment using X-ray absorption spectroscopy (EXAFS/XANES)

- Determine metal loading via inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry (ICP-MS)

Protocol: Electrochemical CO₂ Reduction Testing

Objective: Evaluate the catalytic performance of SACs for electrochemical CO₂ reduction reaction (CO₂RR).

Materials:

- SAC-coated gas diffusion electrode

- CO₂-saturated 0.5M KHCO₃ electrolyte

- H-cell or flow cell electrochemical setup

- Ag/AgCl reference electrode and Pt counter electrode

- Gas chromatograph with thermal conductivity detector

Procedure:

- Electrode Preparation: Prepare catalyst ink by dispersing 5 mg SAC in 1 mL solution (950 μL isopropanol + 50 μL Nafion) and sonicate for 60 minutes.

- Electrode Coating: Uniformly coat the ink onto carbon paper (1×1 cm²) with catalyst loading of 0.5 mg/cm².

- Electrochemical Cell Assembly: Assemble H-cell with Nafion membrane separator, ensuring the SAC electrode serves as working electrode.

- Electrolyte Purge: Purge both compartments with CO₂ for at least 30 minutes to saturate the electrolyte.

- Electrochemical Testing:

- Perform linear sweep voltammetry from 0 to -1.2 V vs. RHE at 5 mV/s

- Conduct potentiostatic tests at various potentials (-0.3 to -1.0 V vs. RHE) for 1 hour each

- Collect gaseous products from the headspace for GC analysis every 15 minutes

- Product Analysis:

- Quantify gaseous products (CO, H₂, CH₄) via GC-TCD

- Analyze liquid products (formate, alcohols) using NMR or HPLC

- Calculate Faradaic efficiency for each product

Quality Control:

- Perform iR compensation to account for solution resistance

- Confirm absence of contaminants in blank tests

- Ensure reproducibility with triplicate measurements

Advanced Characterization Techniques

The precise identification of single-atom structures requires sophisticated characterization methods. The following diagram illustrates the complementary techniques employed:

SAC Characterization Techniques

Protocol: X-ray Absorption Spectroscopy Analysis

Objective: Determine the local coordination environment and electronic state of metal centers in SACs using XAS.

Materials:

- SAC powder sample (50-100 mg)

- Reference compounds (metal foil, metal oxides)

- Polyethylene diluent for homogeneous mixing

- Sample holder with Kapton windows

Procedure:

- Sample Preparation:

- Grind SAC powder with polyethylene diluent (1:10 mass ratio)

- Press mixture into uniform pellet (1 cm diameter)

- Load pellet into sample holder with Kapton windows

Data Collection:

- Collect data at synchrotron beamline with appropriate energy range

- Acquire spectra at metal K-edge or L-edge in transmission or fluorescence mode

- Measure reference compounds (metal foil) simultaneously for energy calibration

XANES Analysis:

- Normalize pre-edge and post-edge regions

- Determine edge position compared to references

- Analyze pre-edge features for coordination symmetry

EXAFS Analysis:

- Extract χ(k) function from raw data

- Fourier transform to R-space

- Fit structural parameters (coordination number, bond distance, Debye-Waller factor)

Interpretation Guidelines:

- Absence of metal-metal scattering paths confirms atomic dispersion

- Dominant metal-heteroatom (M-N, M-O) coordination shells indicate successful SAC formation

- Comparison with reference compounds helps identify oxidation state

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for SAC Development

| Category | Specific Materials | Function | Application Examples |

|---|---|---|---|

| Metal Precursors | Metal acetates (Fe, Co, Ni), Chlorides, Phthalocyanines | Provide metal source for single atoms | M-N-C catalyst synthesis |

| Carbon Supports | Graphene oxide, Carbon black, Mesoporous carbon, ZIF-8 | Anchor single metal atoms, provide conductivity | All SAC applications |

| Nitrogen Sources | Dicyandiamide, Melamine, Phenanthroline, Ammonia | Create coordination sites for metal atoms | M-N-C catalyst synthesis |

| Characterization Standards | Metal foils (Fe, Co, Ni, Cu), Metal oxides | Reference materials for spectroscopy | XAS analysis |

| Electrochemical Materials | Nafion solution, Carbon paper, KP-14 ionomer | Electrode preparation, ion conduction | Fuel cells, electrolyzers |

| Testing Gases | CO₂ (99.999%), CO (99.99%), NO/Ar mixtures | Reaction feedstocks for catalytic testing | CO₂RR, CO-SCR evaluation |

Computational and Machine Learning Approaches

Advanced computational methods have become indispensable tools for SAC design and optimization. Interpretable machine learning techniques, such as Shapley Additive Explanations (SHAP), enable researchers to identify key descriptors governing catalytic performance [18]. For nitrate reduction reactions, these approaches have revealed that favorable activity stems from a delicate balance among three critical factors: low number of valence electrons (Nᵥ), moderate nitrogen doping concentration (D_N), and specific doping patterns [18].

Natural language processing (NLP) techniques have recently emerged as powerful tools for accelerating catalyst discovery. By extracting knowledge from scientific literature and integrating it into high-dimensional vectors, NLP models can identify potential SAC candidates and predict promising material combinations [17]. This approach has been successfully applied to screen SACs for room-temperature sodium-sulfur batteries, identifying cobalt centers anchored to both nitrogen and sulfur atoms (SA Co-N/S) as ideal catalysts for sulfur reduction reactions [17].

Single-atom catalysts represent a transformative advancement in surface science and catalysis research, demonstrating how atomic-scale precision engineering can unlock new catalytic functionalities. While significant progress has been made in synthesizing and characterizing SACs, challenges remain in scaling up production, enhancing stability under industrial conditions, and further elucidating reaction mechanisms [19] [15].

Future research directions will likely focus on increasing active site density, improving resistance to poisoning, and developing sophisticated multi-modal characterization techniques to observe SACs under operational conditions [15]. The integration of artificial intelligence and machine learning with high-throughput experimentation and computational modeling will further accelerate the discovery and optimization of next-generation SACs [20] [18]. As these advanced tools mature, single-atom catalysis will continue to push the boundaries of precision engineering at the atomic scale, enabling more sustainable chemical processes and energy technologies.

Tools and Techniques: Probing and Engineering Catalytic Surfaces

The pursuit of understanding catalytic mechanisms at the atomic level under realistic working conditions is a cornerstone of modern catalysis research. Operando and in situ characterization techniques have emerged as powerful methodologies that enable direct observation of catalyst structure and reaction intermediates during reaction, thereby bridging the pressure and materials gaps between traditional surface science and industrial catalysis. This application note details the principles, methodologies, and experimental protocols for key operando and in situ techniques, including transmission electron microscopy (TEM), X-ray absorption spectroscopy (XAS), and vibrational spectroscopy. By providing structured guidelines for reactor design, data interpretation, and material selection, this document aims to equip researchers with the practical knowledge necessary to implement these advanced characterization methods, accelerate catalyst development, and establish robust structure-activity relationships.

Heterogeneous catalysis forms the foundation of the chemical and energy industries, playing a critical role in processes ranging from large-scale chemical production to sustainable energy technologies such as water-splitting electrolysis, batteries, and fuel cells [21]. The conversion of reactants into desired products occurs at the interface between the solid catalyst and its reactive environment, making the rational design of highly active, stable, and selective catalytic materials dependent on an atomic-level understanding of this interface under working conditions [21].

Traditional ex situ characterization techniques, which analyze catalysts before and after reactions, provide only partial insights as they miss the dynamic structural and chemical evolution occurring during catalysis. The high-vacuum environment of many analytical instruments also often fails to reflect the true structure of catalysts under realistic reaction conditions [21]. In situ characterization involves performing measurements on a catalytic system under simulated reaction conditions, while operando techniques go a step further by probing the catalyst under working conditions while simultaneously measuring its activity [22]. The primary goal of operando methodology is to directly correlate the catalytic performance with the atomic-scale structure of the catalyst, enabling the determination of active sites and the elucidation of reaction mechanisms [22] [21].

This application note frames operando and in situ characterization within the broader context of surface science applications in catalysis research. It provides detailed protocols and experimental guidelines for several key techniques, emphasizing the critical importance of proper reactor design and data interpretation to avoid common pitfalls and mechanistic overreach.

Key Techniques and Methodologies

In Situ and Operando Transmission Electron Microscopy (TEM)

In situ TEM has evolved into a robust methodology for investigating catalysts under conditions closely resembling real-world scenarios. It allows for the direct observation of samples within the TEM instrument under various environments while they undergo dynamic processes induced by external stimuli such as heating, biasing, or gas/liquid environments [21]. When these morphological or compositional changes are simultaneously correlated with measurements of catalytic properties, the approach is termed operando TEM [21].

Experimental Protocol: Gas-Phase Catalysis

Purpose: To directly visualize the structural evolution of catalysts during gas-solid reactions at the atomic scale. Materials:

- Catalyst: Nanoparticulate or nanostructured catalyst dispersed on an electron-transparent substrate.

- Reactor: Specifically designed Micro-Electro-Mechanical System (MEMS)-based gas cell or closed-cell system that can withstand the TEM high-vacuum environment while allowing controlled gas flow [21].

- Gases: High-purity reactant gases and inert carriers.

- Instrumentation: TEM equipped with a gas introduction system, capable of Environmental TEM (ETEM) or using closed-cell technology.

Procedure:

- Sample Preparation: Disperse the catalyst powder onto the MEMS chip or closed-cell windows. Ensure appropriate dispersion to avoid overlapping structures and facilitate clear imaging.

- Reactor Loading: Carefully load the MEMS chip or sealed cell into the dedicated TEM holder following manufacturer protocols.

- System Calibration: Calibrate the gas flow system and heating/bias controls prior to insertion into the TEM.

- Baseline Imaging: Acquire high-resolution images, diffraction patterns, and spectroscopic data of the catalyst in its initial state under high vacuum.

- Reaction Initiation: Introduce the reactant gas mixture at a controlled flow rate and pressure. Simultaneously, apply the external stimulus to initiate the reaction.

- Data Acquisition:

- Record real-time image sequences to track morphological changes, particle sintering, or surface restructuring.

- Acquire electron energy-loss spectroscopy or energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy data at intervals to monitor chemical state changes.

- For operando measurements, integrate with mass spectrometry or gas chromatography to quantify reaction products and correlate structural changes with catalytic activity [21].

- Data Analysis: Analyze the image sequences to quantify dynamics such as particle coalescence, facet reconstruction, or the emergence of transient phases.

Experimental Protocol: Liquid-Phase Electrochemistry

Purpose: To observe catalyst behavior in liquid environments under an applied electrical potential, relevant to electrocatalytic reactions. Materials:

- Catalyst: Thin-film or nanoparticulate electrode.

- Reactor: Liquid cell with electron-transparent windows and integrated electrochemical microelectrodes [21].

- Electrolyte: High-purity electrolyte solution.

- Instrumentation: TEM with liquid holder system, potentiostat.

Procedure:

- Cell Assembly: Load the catalyst onto the working electrode within the liquid cell. Assemble the cell with a thin liquid layer sealed between the silicon nitride windows.

- Electrochemical Setup: Connect the integrated microelectrodes to an external potentiostat.

- Initial Characterization: Image the catalyst in the static liquid environment before applying potential.

- Operando Experiment: Apply a controlled potential or current density while simultaneously recording TEM images and electrochemical data.

- Correlation: Correlate structural transformations with features in the cyclic voltammogram or chronoamperometry data.

X-Ray Absorption Spectroscopy (XAS)

XAS is a powerful element-specific technique used to probe the local electronic and geometric structure of a catalyst, including oxidation state, coordination chemistry, and bond distances [22].

Experimental Protocol

Purpose: To determine the oxidation state and local coordination environment of metal centers in a catalyst under reaction conditions. Materials:

- Catalyst: Powdered sample or thin film.

- Reactor: In situ/operando XAS cell with X-ray transparent windows and capabilities for temperature control, gas flow, and/or electrolyte circulation.

- Instrumentation: Synchrotron beamline capable of XAS measurements.

Procedure:

- Sample Preparation: Prepare a uniform sample bed in the reactor to ensure consistent X-ray absorption.

- Reference Measurement: Collect ex situ XAS data of relevant reference compounds.

- Reaction Conditions: Bring the reactor to the desired reaction conditions.

- Data Collection: Collect a series of X-ray absorption near-edge structure and extended X-ray absorption fine structure spectra over time or under different reaction conditions.

- Data Analysis: Fit the spectra to extract quantitative structural parameters.

Vibrational Spectroscopy (IR and Raman)

Infrared and Raman spectroscopy are sensitive to molecular vibrations, making them ideal for identifying reaction intermediates and products adsorbed on catalyst surfaces [22].

Experimental Protocol: Operando IR Spectroscopy

Purpose: To identify adsorbed species and reaction intermediates during catalytic operation. Materials:

- Catalyst: High-surface-area wafer or reflective disc.

- Reactor: Operando cell with IR-transparent windows and temperature control.

- Instrumentation: FTIR spectrometer.

Procedure:

- Background Collection: Collect a background spectrum under inert atmosphere at reaction temperature.

- Reaction Initiation: Introduce reactants and monitor the evolution of absorption bands.

- Isotope Labeling: Use isotopically labeled reactants to confirm band assignments.

- Activity Correlation: Simultaneously monitor catalytic activity to link specific intermediates to turnover.

Data Presentation and Quantitative Analysis

The effective interpretation of operando and in situ data relies on the correlation of structural information with quantitative activity metrics. The table below summarizes key quantitative insights obtainable from different techniques.

Table 1: Key Operando and In Situ Techniques for Catalysis Research

| Technique | Probed Information | Spatial Resolution | Temporal Resolution | Key Quantitative Metrics |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| In Situ/Operando TEM [21] | Morphology, Crystallography, Composition | Atomic (~50 pm) | Millisecond to second | Particle size distribution, lattice spacing changes, reaction rates from correlated MS/GC |

| XAS [22] | Oxidation State, Local Coordination | -- | Seconds to minutes | Edge energy shift, coordination number, bond distance |

| Vibrational Spectroscopy (IR/Raman) [22] | Surface Species, Molecular Vibrations | ~µm (microscope) | Seconds | Band position & intensity, adsorption constants |

| Electrochemical MS (EC-MS) [22] | Reaction Products/Intermediates | -- | Sub-second | Mass ion counts, Faradaic efficiency |

Table 2: Research Reagent Solutions for Operando Experiments

| Reagent/Material | Function/Description | Key Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| MEMS Reactor Chips [21] | Miniaturized reaction cell for in situ TEM; enables heating, biasing, and gas/liquid flow. | Essential for maintaining high vacuum while creating a localized reaction environment. SiN windows provide electron transparency. |

| Isotopically Labeled Reactants [22] | Molecules with specific atoms replaced with isotopes. | Critical for confirming the origin of spectroscopic signals and tracing reaction pathways. |

| High-Purity Gases/Liquids | Reactants and electrolytes for creating realistic environments. | Purity is paramount to avoid catalyst poisoning and spurious signals. |

| Standard Reference Compounds | Well-defined materials with known structure and composition. | Necessary for calibrating and interpreting XAS and vibrational spectroscopy data. |

| Electrocatalyst Inks | Dispersion of catalyst nanoparticles for electrode preparation. | Used for creating uniform thin-film electrodes in electrochemical operando cells. |

Experimental Workflows and Signaling Pathways

The logical workflow for designing and executing a robust operando study involves multiple stages, from reactor selection to data correlation. The following diagram outlines this critical process.

A fundamental goal of operando characterization is to move from observed structural dynamics to a validated microkinetic model. The logical pathway connecting these elements is illustrated below.

Operando and in situ characterization techniques represent a paradigm shift in catalysis research, moving the field from post-reaction analysis to direct observation under working conditions. The successful implementation of these techniques requires careful attention to reactor design, appropriate use of controls, and the synergistic combination of multiple characterization methods. By adhering to the detailed protocols and best practices outlined in this application note, researchers can robustly elucidate reaction mechanisms, identify active sites, and accelerate the development of next-generation catalysts for sustainable energy and chemical processes. Future advancements will likely focus on closing the remaining gaps between idealized laboratory conditions and industrial operation, improving spatiotemporal resolution, and harnessing machine learning for the analysis of complex, multi-modal operando datasets.

Scanning Electrochemical Microscopy (SECM) is a powerful scanning probe technique designed for measuring in situ electrochemical reactions at various interfaces, including solid-liquid, liquid-liquid, and liquid-gas boundaries [23]. Its unique capability lies in visualizing real-time local catalytic activity with high spatial resolution, offering profound insights for designing novel catalysts and enhancing their performance [23]. The core of SECM is an ultramicroelectrode (UME) or nanoelectrode (NE) probe, which is moved with high precision by a motor positioning system near the sample surface [23]. When applied to catalysis research, SECM operates on the principle of diffusion-controlled feedback. In a typical experiment, a redox mediator (R) in the bulk solution is oxidized at the UME tip to generate a species (O). This generated species diffuses to the catalyst substrate surface. If the substrate is electrochemically active, O can be reduced back to R, creating a positive feedback loop that increases the tip current (iT > iT,∞). Conversely, an inert or insulating substrate causes a negative feedback effect, decreasing the tip current (iT < iT,∞) due to hindered diffusion [23]. Surface Interrogation SECM (SI-SECM) is a specialized mode that directly quantifies adsorbed intermediates and catalytically active sites on a catalyst surface, providing a powerful tool for probing surface coverage and intrinsic catalytic kinetics [24].

Quantitative Data in Catalysis Research

The application of SI-SECM and related techniques yields critical quantitative parameters essential for evaluating electrocatalysts. The following tables summarize key quantitative data and operational modes used in the field.

Table 1: Key Quantitative Parameters Measured by SECM in Electrocatalysis

| Parameter | Description | Significance in Catalysis | Experimental Method |

|---|---|---|---|

Heterogeneous Rate Constant (k⁰) |

Standard rate constant for electron transfer at the electrode-electrolyte interface [25]. | Determines the efficiency of the electron transfer process, crucial for catalyst performance in energy conversion devices [25]. | SECM spot analysis; fitting of kinetic data to Butler-Volmer or Marcus-Hush models [25]. |

Transfer Coefficient (α) |

Empirical parameter describing the symmetry of the energy barrier for electron transfer [25]. | Deviations from 0.5 indicate non-ideal behavior, potentially due to adsorption or interfacial films, affecting overpotential [25]. | Extracted from the potential-dependent profile of k_f or k_b using Butler-Volmer analysis [25]. |

Tip Current (i_T) |

Faradaic current measured at the SECM probe [23]. | Maps local electrochemical activity; feedback mode current indicates substrate reactivity and presence of active sites [23]. | Direct amperometric measurement during probe approach curves or surface scanning. |

Surface Coverage (Γ) |

Quantity of adsorbed intermediates or catalytic sites per unit area [24]. | Directly quantifies the number of active sites available for a reaction, a fundamental property of catalyst activity [24]. | SI-SECM, where a titrant generated at the tip reacts with and quantifies adsorbed species on the substrate. |

Table 2: SECM Operational Modes for Catalysis Research

| Operational Mode | Mechanism | Primary Application in Catalysis |

|---|---|---|

| Feedback Mode (FB) | Measures tip current change due to regeneration (or lack thereof) of redox mediator at the substrate [23]. | Differentiating conductive vs. insulating zones; mapping general electrochemical activity and surface topography [23]. |

| Substrate-Generation/Tip-Collection (SG/TC) | Active substrate generates a product, which is detected at the tip [23]. | Detecting and quantifying short-lived intermediates or products (e.g., O₂, H₂, CO) of catalytic reactions [23]. |

| Tip-Generation/Substrate-Collection (TG/SC) | Tip generates a reactant, which is consumed at the active substrate [23]. | Studying catalytic reactions on the substrate surface by providing a localized source of reactant [23]. |

| Redox Competition (RC) | Both tip and substrate compete for the same redox species in solution [23]. | Probing the catalytic activity of substrates for reactions like the Oxygen Reduction Reaction (ORR) [23]. |

| Surface Interrogation (SI) | Tip generates a titrant that chemically reacts with adsorbed species on the substrate [24]. | Direct quantification of adsorbed intermediates (Hads, Oads) and active site coverage on catalyst surfaces [24]. |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: SI-SECM for Quantifying Adsorbed Intermediates

This protocol details the use of SI-SECM to quantify the surface coverage of an oxygen species (O_ads) on a catalyst surface (e.g., a metal oxide) following water oxidation.

- Step 1: Substrate Preparation. Immerse the catalyst substrate of interest (e.g., a thin film deposited on a conductive electrode) in a deaerated electrolyte solution (e.g., 0.1 M NaOH). Ensure the substrate is firmly fixed in the SECM cell [23].

- Step 2: Surface Pre-conditioning. Apply a potential pulse to the catalyst substrate to trigger the water oxidation reaction, leading to the formation of an adsorbed oxygen species (

O_ads). Hold the potential for a controlled time to build up a measurable coverage [24]. - Step 3: Switching to Open-Circuit Potential (OCP). Disconnect the substrate from the potentiostat (switch to OCP) to halt faradaic reactions. The

O_adsspecies remains on the surface [24]. - Step 4: Tip Positioning. Position the SECM tip (e.g., a Pt UME,

r_T = 5 µm) at a constant, close distance (e.g.,d = 5 µm, normalized distanceL = d/r_T = 1) from the substrate surface using an approach curve in a solution containing a inert redox mediator (e.g., 1 mM[Fe(CN)₆]⁴⁻) [25] [23]. - Step 5: Titrant Generation and Interrogation. With the substrate still at OCP, step the tip potential to oxidize a solution-phase reductant (e.g.,

[Ru(NH₃)₆]²⁺) to generate a strong titrant (e.g.,[Ru(NH₃)₆]³⁺). This titrant diffuses to the substrate and chemically reduces the adsorbedO_ads[24]. - Step 6: Charge Measurement. Monitor the tip current transient during the titration. The total charge passed at the tip to replenish the titrant consumed by the surface reaction is directly proportional to the surface coverage of

O_ads(Γ_O). CalculateΓ_Ousing the formula:Γ_O = Q / (nFA), whereQis the measured charge,nis the number of electrons transferred perO_adsmolecule,Fis Faraday's constant, andAis the interrogated surface area [24].

Protocol 2: Spot Analysis for Electron Transfer Kinetics

This protocol describes a spot analysis method to quantify the heterogeneous electron transfer kinetics between a redoxmer and an electrode material, relevant to redox flow battery research [25].

- Step 1: Solution Preparation. Prepare a solution of the redox-active molecule (e.g., 1.0 mM Ferrocene, Fc) in a non-aqueous solvent (e.g., propylene carbonate) with a supporting electrolyte (e.g., 0.1 M TBAPF₆) [25].

- Step 2: System Setup. Insert the substrate electrode (e.g., Glassy Carbon, HOPG) and the SECM tip (a Pt UME with

a = 1 µmandR_G = 10) into the solution. Use a standard three-electrode configuration for both tip and substrate [25] [23]. - Step 3: Distance Calibration. Perform a probe approach curve in a solution containing a fast redox couple (e.g., 1 mM

Fc/Fc⁺) to determine and set the tip-substrate distance to a known value (e.g.,L = 1) [25]. - Step 4: Chronoamperometric Measurement. Hold the tip potential at a value sufficient for the mass-transfer-limited oxidation of Fc to Fc⁺ (e.g.,

E_tip - E⁰' = +0.2 V). At the substrate, apply a series of chronoamperometric steps across a potential window (e.g., fromE_sub - E⁰' = +0.15 Vto-0.15 V), with each step lasting 12 seconds [25]. - Step 5: Data Collection. Record the tip current (

i_T) during the final 2 seconds of each substrate potential step, once a steady state is reached. Normalize these currents by the tip current measured when the substrate is inactive (i_T,∞) [25]. - Step 6: Kinetic Analysis. Plot the normalized tip current

(i_T / i_T,∞)against the substrate potential(E_sub - E⁰'). Use established theory [citation:15 in citation:3] to convert the normalized current values into the heterogeneous electron transfer rate constant (k_fork_b) [25]. - Step 7: Parameter Extraction. Plot

log(k_f)versus(E_sub - E⁰'). Fit the linear region of this plot to the Butler-Volmer equation (Eq. 1:k_f = k⁰ exp[-αf(E-E⁰')]) to extract the standard heterogeneous rate constantk⁰and the transfer coefficientα[25].

Visualization of Workflows and Signaling Pathways

Diagram 1: SI-SECM Workflow for Quantifying Adsorbed Intermediates. This diagram outlines the step-by-step process for using Surface Interrogation SECM to measure the surface coverage of species on a catalyst.

Diagram 2: SECM Feedback Modes Signaling Diagram. This diagram illustrates the mediator regeneration pathways and resulting tip current for positive and negative feedback modes, which underpin the interpretation of SECM data.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for SI-SECM

| Item Name | Function/Application | Specific Examples & Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Ultramicroelectrode (UME) | The core scanning probe; acts as the working electrode for generating or detecting redox species [23]. | Pt (for general use), Carbon fiber (for bio-applications); tip radius typically 1-25 µm. Soft UMEs allow scanning of rough/curved surfaces [23]. |

| Redox Mediators | Freely diffusing species used to probe the substrate activity via feedback or as a titrant in SI-SECM [25] [23]. | Ferrocene/Ferrocenium (Fc/Fc⁺): Common in non-aqueous studies [25]. [Ru(NH₃)₆]²⁺/³⁺: Used as a titrant in SI-SECM [24]. [Fe(CN)₆]⁴⁻/³⁻: Common in aqueous studies. Must be inert towards the substrate except for the intended reaction. |

| Supporting Electrolyte | Carries current in the solution, minimizes ohmic drop (iR drop), and controls the double-layer structure [25]. | TBAPF₆ (Tetrabutylammonium hexafluorophosphate) for non-aqueous solvents. KCl or Na₂SO₄ for aqueous solutions. Use high-purity salts. |

| Non-aqueous Solvents | Enable study of redox systems with high operating potentials or poor water solubility [25]. | Propylene Carbonate (PC), Acetonitrile (ACN). Must be thoroughly dried and deaerated for non-aqueous RFB studies [25]. |

| Electrode Substrates | The catalyst materials under investigation [25]. | Glassy Carbon (GC), Highly Ordered Pyrolytic Graphite (HOPG), Multi-layer Graphene (MLG), Pt, metal oxides. Surfaces should be clean and well-polished before use [25]. |

| Potentiostat | Controls the potential of the working electrode(s) and measures the resulting current [23]. | A bipotentiostat is required for SECM to independently control the tip and substrate potentials. |

| Precision Positoning System | Moves the UME probe with sub-micrometer precision in x, y, and z directions [23]. | Piezoelectric stepper motors or similar systems are used for accurate approach curves and surface scanning. |

The discovery of new catalysts is a critical step in developing more efficient and sustainable chemical processes, a core pursuit in surface science and catalysis research. Traditional experimental methods, however, are often slow, expensive, and ill-suited for exploring the vast landscape of potential materials. The integration of computational screening and machine learning (ML) has emerged as a transformative approach, enabling the rapid identification of promising catalyst candidates from thousands of possibilities by linking atomic-scale properties to catalytic performance [26] [6]. These methods leverage high-throughput computation to generate massive datasets, which machine learning models then analyze to uncover complex patterns and predict new materials with desired activities, thereby accelerating the entire discovery pipeline [27] [28]. This document outlines key protocols and applications, framing them within the broader thesis that surface science fundamentals, when augmented by computational power and data-driven modeling, are pivotal for the next generation of catalyst design.

Application Note: Descriptor-Driven Discovery for CO₂ to Methanol Conversion

Background and Objective

Converting CO₂ into methanol represents a crucial step towards closing the carbon cycle and reducing emissions [26]. However, existing catalysts, often based on Cu/ZnO/Al₂O₃, suffer from challenges like low conversion rates and poor stability. The objective of this application note is to detail a computational workflow for discovering new, stable bimetallic catalysts for this reaction using a novel, machine learning-accelerated descriptor.

Protocol: Workflow for Adsorption Energy Distribution (AED) Screening

The following protocol describes the steps for a large-scale screening of metallic alloys using Adsorption Energy Distributions (AEDs) as a central descriptor [26].

Step 1: Search Space Selection

- Identify metallic elements previously experimented with for CO₂ thermal conversion.

- Filter these elements to those present in the Open Catalyst 2020 (OC20) database to ensure compatibility with pre-trained machine learning force fields (MLFFs). The final shortlist includes: K, V, Mn, Fe, Co, Ni, Cu, Zn, Ga, Y, Ru, Rh, Pd, Ag, In, Ir, Pt, and Au.

- Query the Materials Project database for stable and experimentally observed crystal structures of these metals and their bimetallic alloys.

Step 2: Surface and Adsorbate Configuration

- Surface Generation: For each identified material, generate surfaces with Miller indices in the range

{-2, -1, ..., 2}. Use tools from repositories likefairchem[26] to create these surfaces and select the most stable surface termination for each facet. - Adsorbate Selection: Based on literature review of reaction intermediates in CO₂ to methanol conversion, select key adsorbates: H (hydrogen atom), OH (hydroxy group), OCHO (formate), and OCH₃ (methoxy).

- Surface Generation: For each identified material, generate surfaces with Miller indices in the range

Step 3: High-Throughput Energy Calculation with MLFF

- Engineer surface-adsorbate configurations for all selected materials, facets, and adsorbates.

- Optimize these configurations using a pre-trained MLFF, such as the OCP

equiformer_V2model. This step replaces computationally intensive Density Functional Theory (DFT) calculations, providing a speed-up by a factor of 10⁴ or more while maintaining quantum mechanical accuracy [26].

Step 4: Validation and Data Cleaning

- Benchmarking: Validate the MLFF's accuracy by comparing its predicted adsorption energies for a subset of materials (e.g., Pt, Zn, NiZn) against explicit DFT calculations. An acceptable Mean Absolute Error (MAE), for instance, below 0.2 eV, should be achieved [26].

- Data Cleaning: Exclude materials for which surface-adsorbate supercells are too large for practical computation. Sample the minimum, maximum, and median adsorption energies for each material-adsorbate pair to ensure data quality.

Step 5: Descriptor Calculation and Analysis

- Construct AEDs: For each candidate material, aggregate the computed adsorption energies across all facets and binding sites to form an Adsorption Energy Distribution (AED) for each adsorbate. The AED serves as a fingerprint of the material's catalytic property.

- Compare and Cluster: Treat AEDs as probability distributions. Use a metric like the Wasserstein distance (Earth Mover's distance) to quantify the similarity between the AED of a new material and that of a known high-performance catalyst [26]. Apply unsupervised machine learning (e.g., hierarchical clustering) to group materials with similar AED profiles and identify promising candidates.

Key Research Reagents and Computational Tools

Table 1: Essential Research Reagents and Tools for Computational Screening

| Item Name | Function/Description | Example/Source |

|---|---|---|

| OC20 Dataset | A comprehensive dataset of ~1.3 million DFT relaxations used for training MLFFs, providing the foundational data for accurate energy predictions. | Open Catalyst Project [26] |

| ML Force Field (MLFF) | A pre-trained machine learning model that predicts energies and forces on atomic structures, enabling rapid relaxation of adsorbates on catalyst surfaces. | OCP equiformer_V2 [26] |

| Materials Project | An open database of computed materials properties, used to source stable crystal structures for screening. | materialsproject.org [26] |

| fairchem | A repository of software tools and models, facilitating the application of MLFFs to catalytic problems. | Open Catalyst Project [26] |