Surface Science in Pharmaceuticals: A Beginner's Guide to Improving Drug Development and Delivery

This guide provides a comprehensive introduction to surface science, demystifying its critical role in pharmaceutical research and development.

Surface Science in Pharmaceuticals: A Beginner's Guide to Improving Drug Development and Delivery

Abstract

This guide provides a comprehensive introduction to surface science, demystifying its critical role in pharmaceutical research and development. Tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, it explores the fundamental principles of surface interactions, details practical measurement techniques, and offers strategies for troubleshooting common formulation challenges. By connecting theory with real-world applications—from improving drug solubility and stabilizing emulsions to optimizing packaging—this article equips beginners with the knowledge to leverage surface science for creating safer, more effective, and more reliable drug products.

Surface Science Fundamentals: Core Principles and Their Impact on Drug Product Performance

In the intricate world of drug development, therapeutic proteins and other biologic products encounter a multitude of environmental stresses long before they reach their intended targets within the human body. Among the most significant, yet often overlooked, of these stresses are interfacial phenomena—the complex physical and chemical events that occur at the boundaries between different phases of matter. When proteins come into contact with vapor–liquid, solid–liquid, and liquid–liquid surfaces, these interfaces can profoundly impact critical quality attributes of the drug product [1]. The consequences include the formation of visible and subvisible particles, the development of soluble aggregates, and a reduction in target protein concentration due to adsorption [1]. Understanding and mitigating these interfacial stresses is not merely an academic exercise; it is an essential component of developing safe, stable, and efficacious biologic medicines, particularly as the industry increasingly shifts toward novel and complex modalities [2].

The importance of interfaces extends across the entire hierarchy of biologic function. At the molecular level, the design of the interface between target molecules and pharmaceutical compounds is a critical determinant of efficacy for molecularly targeted drugs [3]. At the cellular level, the plasma membrane serves as the primary interface between the cell's interior and the extracellular space, representing a key targeting site for many therapeutics [3]. Even in the context of administration, drug interactions with surface-active components in biological systems (such as pulmonary surfactants in the alveoli) present crucial challenges and considerations for drug delivery and functionality [4]. This whitepaper provides a comprehensive examination of interfacial phenomena throughout the drug development lifecycle, offering technical insights and practical methodologies for researchers and scientists working to advance the next generation of biologic therapies.

The Impact of Interfacial Stress on Protein Therapeutics

Fundamental Mechanisms of Interfacial-Induced Aggregation

Protein aggregation at interfaces represents one of the most significant challenges in biologic formulation development. This process typically involves some degree of protein conformational change relative to the folded monomer, enabling two or more protein molecules to form interprotein bonds that possess stability comparable to or greater than the intraprotein bonds of the native structure [1]. The growth of aggregates generally occurs through the addition of monomers or through the combination of existing aggregates to form soluble high molecular weight (HMW) species [1].

The precise mechanism through which interfacial stresses promote protein aggregation differs fundamentally from aggregation pathways in bulk solution. When proteins adsorb to interfaces, they undergo significant structural rearrangement, often exposing internal hydrophobic residues that become attached to the interface [4]. This unfolding is driven by the tendency of hydrophobic regions to minimize contact with aqueous environments, making interfaces particularly disruptive to protein tertiary structure. While long-term exposure to interfaces alone can be detrimental to protein stability, the combination of interfacial exposure with mechanical disruption (e.g., agitation, mixing, pumping) proves particularly damaging to therapeutic proteins [1].

Table 1: Types of Interfacial Stresses in Biologics Development

| Interface Type | Sources in Development | Primary Impact on Proteins |

|---|---|---|

| Vapor-Liquid | Mixing operations, headspace in containers, filling processes | Protein unfolding at air-water interface, surface denaturation |

| Solid-Liquid | Filters, chromatography columns, container surfaces, tubing | Adsorption to solid surfaces, shear stress during flow |

| Liquid-Liquid | Silicone oil in pre-filled syringes, lipid emulsions | Partitioning at oil-water interfaces, structural rearrangement |

| Ice-Liquid | Freezing and thawing processes | Concentration at ice crystal boundaries, cold denaturation |

Interfacial protein films exhibit markedly different properties compared to proteins in solution. Proteins diffuse slowly to interfaces and form viscoelastic adsorbed layers that function via steric effects, often creating an interfacial network structure that renders the adsorbed layer practically irreversible [4]. This stands in stark contrast to the behavior of low molecular-weight surfactants, which stabilize interfaces via the Marangoni mechanism by compensating for interfacial tension gradients [4]. The irreversibility of protein adsorption contributes to the particular challenges of interfacial stress, as once proteins have denatured at an interface, they may shed into the bulk solution as aggregates even after the initial stress has been removed [1].

Quantitative Impact on Product Quality and Efficacy

The consequences of interfacial stress extend beyond abstract scientific concerns to direct impacts on critical quality attributes that determine the safety and efficacy of biologic products. Aggregates formed through interfacial denaturation may elicit immunogenic responses in patients, raising significant safety concerns [1]. Additionally, the loss of active protein through adsorption or irreversible aggregation can reduce the effective dose delivered to patients, potentially compromising therapeutic outcomes.

Industry case studies provide compelling evidence of these impacts. For one marketed biologic, LUMIZYME (Genzyme Corporation), the prescribing instructions explicitly direct healthcare providers to remove air from intravenous (IV) bags prior to administration "to minimize particle formation because of the sensitivity of LUMIZYME to air–liquid interfaces" [1]. Experimental studies have further demonstrated that agitation of monoclonal antibodies in drug product vials with air headspace leads to extensive aggregation, while otherwise identical conditions without the air headspace substantially limit aggregation [1]. Similarly, research has shown that the presence of silicone oil in prefilled syringes exacerbates agitation-induced aggregation across a range of protein therapeutics [5] [6].

Table 2: Quantitative Impacts of Interfacial Stress on Protein Therapeutics

| Parameter Affected | Measurement Technique | Typical Range of Impact |

|---|---|---|

| Soluble Aggregates | Size-exclusion chromatography (SEC-HPLC) | 0.1% to >10% increase in HMW species |

| Subvisible Particles | Microflow imaging (MFI), light obscuration | 10,000 to >100,000 particles/mL ≥10μm |

| Visible Particles | Visual inspection | Presence of particulates in previously clear solutions |

| Concentration Loss | UV-Vis spectroscopy, HPLC | 1% to >15% loss due to adsorption |

The effect of interfacial stress often demonstrates an inverse relationship with protein concentration, as protein adsorption to interfaces is frequently limited to the formation of a monolayer rather than multilayers [1]. Consequently, formulations with lower protein concentrations typically show a higher percentage of aggregate formation relative to total protein when exposed to the same interfacial stress conditions. This relationship highlights the importance of considering interfacial phenomena across the entire range of clinical use cases, including scenarios where highly diluted solutions are administered via IV infusion.

Interfacial Stressors Across the Drug Development Workflow

Drug Substance Manufacturing

The journey of a biologic therapeutic begins with drug substance manufacturing, where the protein undergoes a series of unit operations that present multiple opportunities for interfacial stress. These include harvest, centrifugation or filtration for removal of cell debris, purification via column chromatography, various filtration steps, virus reduction, concentration, and formulation for storage [1]. Throughout this process, the molecule encounters numerous solid-liquid interfaces through interaction with filters, chromatography resins, and the surfaces of processing equipment and storage containers.

Filtration operations represent a particularly significant source of interfacial stress during drug substance manufacturing. Multiple normal flow filters are typically placed throughout the process, including particle reduction or microbial control filters before the load and pools of each process step [1]. During ultrafiltration/diafiltration (UF/DF) processes—membrane-based tangential flow filtration (TFF) operations used for concentration and buffer exchange—proteins experience multiple pump passes, recirculation, and mixing, resulting in extended exposure to solid-liquid interfaces under high shear conditions [1].

Freezing and thawing operations present another critical interfacial stress point. During freezing, proteins become excluded from the forming ice crystals, leading to significant concentration at the ice-liquid interface and potential cold denaturation. The thawing process similarly exposes proteins to these ice-liquid interfaces, creating opportunities for aggregation and structural damage. The cumulative effect of these stresses throughout the drug substance manufacturing process can significantly impact protein stability and must be carefully evaluated and controlled to ensure product quality.

Drug Product Manufacturing and Administration

Once the drug substance has been manufactured, the transition to drug product introduces another set of interfacial challenges. The thawing process exposes the protein to ice-liquid interfaces, after which mixing operations introduce exposure to the air-water interface under shear conditions [1]. The filling process then subjects the molecule to high shear for short periods, further increasing the risk of interfacial damage.

Primary packaging represents another significant source of interfacial stress. Pre-filled syringes, while offering convenience for administration, typically contain silicone oil that serves as a lubricant for the plunger. When proteins come into contact with this silicone oil-water interface, they often undergo structural changes that can lead to aggregation [1] [5]. Additionally, the headspace within vials and syringes creates an air-liquid interface that can denature proteins, particularly when combined with agitation during shipping and transportation.

The final stage of a therapeutic protein's journey—clinical administration—presents perhaps the most challenging interfacial environment to control. Administration typically occurs using IV bags, syringes, or autoinjectors, where the protein encounters a variety of surfaces and materials, including plastics from IV bags and infusion sets, in-line filters, silicone oil, and metals [1]. Particularly concerning is the substantial aggregation that can occur in IV infusion bags due to the air-liquid interface present in the bags, especially when surfactants in the formulation become diluted [1]. Research has demonstrated that simply removing the air headspace to eliminate the air-liquid interface in IV bags allows them to undergo agitation with essentially no protein aggregation [1].

Essential Experimental Techniques for Characterizing Interfacial Phenomena

Techniques for Interfacial Characterization

Understanding and quantifying protein behavior at interfaces requires specialized analytical approaches that can probe the unique environment presented by interfaces. Several well-established techniques provide critical insights into interfacial phenomena:

Dynamic surface tensiometry serves as a fundamental macroscopic approach that provides adsorption isotherms and equations of state for protein-surfactant mixed layers, revealing essential molecular properties such as surface activity parameters [4]. The adsorption isotherms of mixed protein-surfactant solutions can exhibit up to three distinct deflection points, each providing valuable data on their interactions: the first indicating a critical aggregation concentration where the binding regime switches from monomeric to cooperative; the second representing the protein saturation point where the protein becomes saturated with surfactant; and the third corresponding to the critical micelle concentration (CMC) where free surfactant monomers form micelles in equilibrium with protein-surfactant complexes [4].

Interfacial dilational rheology offers a powerful complementary technique that can detect conformational transitions in the adsorbed layer and distinguish between different adsorption steps [4]. This method has revealed significant differences in the viscoelastic properties of globular versus unfolded proteins and their complexes with surfactants. The frequency dependency of elasticity values serves as a particularly useful experimental protocol for differentiating small and large components (surfactants versus proteins) in mixed adsorption layers [4].

Interfacial shear rheology provides crucial information on the interactions and molecular structure of the adsorbed layer, typically employing torsion pendulum methods to characterize the mechanical properties of interfacial films [4]. This technique has been extensively applied to study protein-surfactant layers and offers insights into the structural organization and strength of interfacial networks.

Experimental Techniques for Interface Characterization

Advanced Methodologies: CDC-PAT

The coaxial double capillary paired with drop profile analysis tensiometry (CDC-PAT) represents a significant advancement in interfacial characterization technology [4]. This system combines the capabilities of profile analysis tensiometry (PAT)—which measures dynamic surface and interfacial tensions while exploring the dilational rheology of adsorbed layers through interfacial area perturbations—with a coaxial double capillary that enables exchange of the subphase of a droplet while keeping the adsorbed layer intact [4]. This configuration enables researchers to implement systematic approaches for investigating the sequential and simultaneous adsorption/desorption of different components at the same interface.

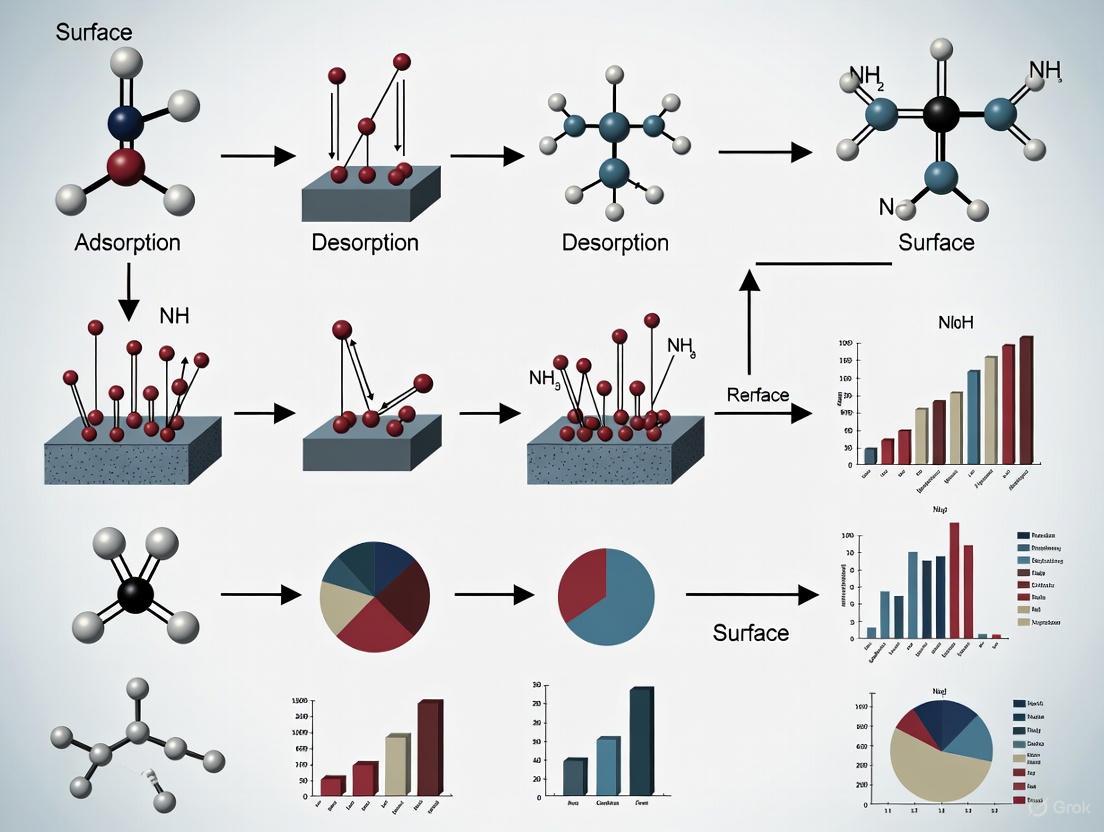

The CDC-PAT technique supports two primary experimental schemes for studying protein-surfactant interactions: simultaneous and sequential drop bulk exchange during the adsorption process [4]. In simultaneous adsorption processes, proteins and surfactants are pre-mixed in solution, competing to adsorb to an interface concurrently. In sequential adsorption approaches, protein and surfactant solutions are prepared separately and injected into the measuring system at different stages of the experiment, allowing researchers to study how pre-adsorbed protein layers interact with subsequently introduced surfactants, and vice versa [4].

This methodology has been successfully applied to study the interactions of various proteins (including bovine serum albumin, lipase, and lysozyme) with diverse ionic and nonionic surfactants (such as CTAB, DTAB, SDS, and Triton X-114) [4]. When analyzed alongside dynamic tensiometry and dilational rheology data, results from CDC-PAT experiments can reveal fundamental aspects of interfacial protein-surfactant interactions, including displacement mechanisms, complex formation, and structural reorganization at interfaces.

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Interfacial Studies

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Primary Function in Experiments |

|---|---|---|

| Model Proteins | Bovine Serum Albumin (BSA), Lipase, Lysozyme | Representative proteins for studying interfacial behavior |

| Ionic Surfactants | CTAB, DTAB, SDS | Investigate charge-based protein-surfactant interactions |

| Nonionic Surfactants | Triton X-114 | Study hydrophobic interactions without charge effects |

| Buffer Components | Phosphates, Citrates, Tris | Control pH and ionic strength conditions |

| Stability Indicators | Fluorescent dyes, Quenchers | Probe conformational changes and binding events |

Detailed Experimental Protocol: Competitive Adsorption Study

The following step-by-step methodology outlines a comprehensive approach for investigating competitive adsorption between proteins and surfactants using the CDC-PAT technique:

Step 1: System Preparation and Calibration

- Ensure the CDC-PAT instrument is properly calibrated according to manufacturer specifications.

- Prepare protein and surfactant solutions in appropriate buffer systems at precisely defined concentrations.

- Conduct preliminary measurements to determine the critical micelle concentration (CMC) of surfactants and the adsorption kinetics of proteins alone.

Step 2: Initial Interfacial Layer Formation

- Create a pendant drop of the protein solution using the primary capillary of the CDC-PAT system.

- Monitor the dynamic surface tension until equilibrium is reached, indicating complete formation of the protein adsorption layer.

- Perform interfacial dilational rheology measurements to characterize the mechanical properties of the pure protein layer.

Step 3: Subphase Exchange Introduction

- Initiate the subphase exchange process using the coaxial double capillary, carefully introducing surfactant solution while preserving the pre-formed protein layer at the interface.

- Maintain constant control over the exchange rate to minimize mechanical disturbance of the interfacial layer.

- Continuously monitor surface tension throughout the exchange process to detect any immediate changes in interfacial composition.

Step 4: Sequential Adsorption Monitoring

- Following subphase exchange, continue monitoring interfacial tension for an extended period to observe competitive adsorption dynamics.

- Perform periodic dilational rheology measurements to assess changes in interfacial viscoelasticity resulting from protein-surfactant interactions.

- Correlate temporal changes in interfacial mechanics with compositional changes at the interface.

Step 5: Displacement and Complement Analysis

- For displacement studies, reverse the process by starting with a surfactant layer and subsequently introducing protein solution.

- Compare the competitive adsorption behaviors between protein-first versus surfactant-first scenarios.

- Analyze the hysteresis effects and irreversibility of adsorption for each component.

Step 6: Data Integration and Model Validation

- Integrate results from tensionetry, dilational rheology, and subphase exchange experiments to develop a comprehensive understanding of the competitive adsorption process.

- Compare experimental findings with theoretical adsorption models, such as the Frumkin-based approaches for mixed protein/surfactant solutions.

- Validate proposed interaction mechanisms through multiple experimental replicates and statistical analysis.

This protocol provides a robust methodology for elucidating the complex competitive adsorption behaviors that occur at interfaces in biopharmaceutical formulations, offering insights critical for developing effective stabilization strategies.

Mitigation Strategies and Industry Best Practices

Formulation Approaches to Minimize Interfacial Stress

Effective management of interfacial stress begins with rational formulation design aimed at minimizing protein adsorption and denaturation at interfaces. The most widely employed strategy involves the incorporation of nonionic surfactants, such as polysorbates (e.g., Tween 80) or poloxamers (e.g., Pluronic F68), which function by competing with proteins for interfacial occupancy [1] [4]. These surfactant molecules typically diffuse more rapidly to interfaces than proteins and form a protective layer that prevents direct contact between the protein and the stressful interface. The effectiveness of this approach depends on multiple factors, including surfactant concentration relative to the critical micelle concentration (CMC), the surfactant's hydrophilic-lipophilic balance (HLB), and the specific characteristics of the protein involved.

Optimization of solution conditions represents another fundamental approach for mitigating interfacial stress. Parameters such as pH, ionic strength, and buffer composition can significantly influence protein stability and interfacial behavior. By adjusting these parameters to maximize the free energy required for protein unfolding, formulators can enhance native state stability and reduce the propensity for interfacial denaturation. Additionally, strategic selection of stabilizing excipients such as sugars, polyols, and amino acids can further strengthen protein resistance to interfacial stress through mechanisms such as preferential exclusion, which increases the free energy penalty for unfolding.

Interfacial Stress Mitigation Strategies

Process and Container Closure System Optimization

Beyond formulation approaches, strategic modifications to manufacturing processes and primary packaging can significantly reduce interfacial stress. For unit operations involving substantial fluid transfer or agitation, engineering controls should focus on minimizing air entrainment and reducing shear forces. In some cases, implementing headspace reduction techniques—such as sparging with inert gases or using pressurized systems—can effectively eliminate vapor-liquid interfaces during critical processing steps. For freezing and thawing operations, controlled rate protocols and the use of appropriate cryoprotectants can mitigate stress at the ice-liquid interface.

The selection and engineering of primary container closure systems requires careful consideration of interfacial phenomena. For pre-filled syringes, optimization of silicone oil levels and distribution can reduce protein interaction with this challenging interface [1] [5]. Alternative lubrication technologies, including silicone oil-free platforms using proprietary polymer coatings, offer promising approaches for mitigating interfacial stress in delivery systems. For vial presentations, careful selection of stopper formulations and processing conditions can minimize extractables and leachables that might exacerbate interfacial instability.

Analytical Control Strategies

Implementing a comprehensive analytical control strategy is essential for monitoring and controlling interfacial stress throughout the product lifecycle. This should include orthogonal methods capable of detecting and quantifying the various manifestations of interfacial damage, including subvisible particles, soluble aggregates, and chemical modifications. Robust compatibility studies using actual administration equipment (e.g., IV bags, infusion sets, in-line filters) under clinically relevant conditions are particularly important for identifying potential interfacial stress issues that might emerge during patient administration [1].

Industry best practices recommend employing a risk-based approach to interfacial stress assessment, focusing attention on unit operations and product configurations with the highest potential for interfacial damage. This includes particularly stressful processes such as filtration, mixing, and freezing/thawing, as well as administration scenarios involving dilution into IV bags. For high-risk products, implementing real-time monitoring of interfacial stress indicators during manufacturing can provide early warning of potential quality issues and enable proactive intervention. By systematically addressing interfacial phenomena throughout development and manufacturing, biopharmaceutical companies can significantly enhance the quality, stability, and clinical performance of protein therapeutics.

Interfacial phenomena present both significant challenges and opportunities in the development of biologic therapeutics. As the industry continues to advance toward increasingly complex modalities—including monoclonal antibodies, antibody-drug conjugates, bispecific antibodies, and various cell and gene therapies [2]—the critical importance of interfacial understanding will only intensify. The comprehensive integration of interfacial assessment throughout the drug development lifecycle, from initial candidate screening through commercial manufacturing and administration, represents an essential paradigm for ensuring the successful development of stable, efficacious, and safe biopharmaceutical products.

Future advancements in the field will likely emerge from continued innovation in analytical technologies, such as the CDC-PAT system [4], that enable more sophisticated characterization of interfacial behavior. Additionally, the development of computational models capable of predicting protein interfacial properties from sequence and structural information would represent a transformative capability for rational formulation design. As our understanding of interfacial phenomena deepens, so too will our ability to engineer solutions that mitigate their negative consequences while potentially harnessing interfacial interactions for beneficial purposes such as controlled release or targeted delivery. Through continued scientific advancement and systematic application of interfacial science, the biopharmaceutical industry can overcome these challenging phenomena to deliver increasingly effective therapies to patients worldwide.

Surface tension, wettability, and surface energy are fundamental interfacial phenomena that govern the behavior of liquids and solids across numerous scientific and industrial applications. These concepts are particularly crucial in fields such as drug development, where they influence processes including drug formulation, coating efficacy, and the performance of inhalable medications. Surface tension is a property of liquids that arises from the cohesive forces between molecules at the air-liquid interface, creating an effect akin to an elastic membrane under tension [7]. Wettability describes the ability of a liquid to maintain contact with a solid surface, determined by the balance between adhesive forces (liquid-solid attraction) and cohesive forces (liquid-liquid attraction) [8]. Surface energy is the solid-phase equivalent of surface tension, representing the excess energy at the surface of a solid compared to its bulk [8] [9]. A comprehensive understanding of the relationships between these three properties is essential for researchers and scientists seeking to optimize product performance in applications ranging from pharmaceuticals and coatings to medical devices and ink printing.

Surface Tension

Fundamental Principles

Surface tension (γlv) is a physical property of liquids that results from the cohesive forces between liquid molecules. Molecules within the bulk of a liquid experience equal attractive forces in all directions, whereas molecules at the surface experience a net inward pull due to the lack of similar molecules above them. This creates a state of tension that causes the liquid surface to behave like a stretched elastic membrane, minimizing its surface area [7]. Surface tension is quantitatively defined as the force per unit length acting parallel to the surface (units of mN/m) or as the work required to increase the surface area by a unit amount (units of mJ/m²). This property is responsible for a variety of everyday phenomena, from the spherical shape of droplets to the ability of small insects to walk on water.

Measurement Methodologies

Several established laboratory methods exist for measuring surface and interfacial tension, each with specific protocols, advantages, and applications. The three primary techniques are two force-based methods (Du Noüy ring and Wilhelmy plate) and one optical method (pendant drop) [10].

Du Noüy Ring Method

The Du Noüy ring method utilizes a platinum ring as the probing element [10].

- Experimental Protocol: The platinum ring is suspended from a highly sensitive balance and submerged into the liquid by lowering the platform holding the liquid container. After immersion, the platform height is gradually decreased, causing the ring to pull through the interface while drawing a meniscus of liquid with it. The measurement is based on the maximum force exerted on the ring before the liquid meniscus tears. The surface tension is calculated from this maximum force and the known perimeter of the ring [10].

- Key Considerations: The maximum force occurs just before the meniscus ruptures, not at the actual tearing event. The method is well-suited for equilibrium surface and interfacial tension measurements.

Wilhelmy Plate Method

The Wilhelmy plate method uses a thin, rough platinum plate as the probe [10].

- Experimental Protocol: The platinum plate is suspended from the balance and the liquid container is raised until the plate just contacts the liquid surface. This contact point is registered as a change in force and labeled the "zero depth of immersion." The plate is then immersed to a set depth (typically a few millimeters) and subsequently returned to the zero immersion position, with the force being recorded at this point. The calculation of surface tension uses this force value and the full wetted perimeter of the plate [10].

- Key Considerations: The plate must be completely wetted for an accurate measurement. A variation using a platinum rod is possible for smaller sample volumes, though with reduced accuracy compared to the standard plate [10].

Pendant Drop Method

The pendant drop method is an optical technique that analyzes the shape of a droplet suspended from a needle [10].

- Experimental Protocol: A droplet is dispensed from a syringe needle and allowed to hang freely in an immiscible surrounding phase (e.g., air or oil). The profile of the droplet is captured using a high-resolution camera. Modern software then performs an iterative fitting process based on the Young-Laplace equation, which describes the balance between surface tension (which tends to make the drop spherical) and gravity (which causes elongation). The surface tension is derived from the optimized fit between the theoretical and actual droplet shapes [10].

- Key Considerations: The droplet must have a proper pendant or tear shape for the analysis to be valid. This method is particularly useful for measuring interfacial tension between two immiscible liquids.

Table 1: Comparison of Primary Surface Tension Measurement Methods

| Method | Principle | Probe | Key Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Du Noüy Ring | Force Tensiometry | Platinum Ring | Equilibrium surface/interfacial tension [10] |

| Wilhelmy Plate | Force Tensiometry | Platinum Plate or Rod | Equilibrium surface tension; dynamic contact angle [10] [9] |

| Pendant Drop | Optical Tensiometry | Liquid Droplet from Needle | Surface/interfacial tension of small volumes [10] |

Practical Quality Control Method: Test Inks

For rapid industrial quality control, such as checking substrate wettability before printing, surface tension test inks provide a practical semi-quantitative approach [7].

- Experimental Protocol: Test inks are formulated with known surface tension values (e.g., in mN/m). A tester applies a stroke of high-tension ink to the pretreated surface with a brush. If the ink stroke remains even and stable for at least 2 seconds without retracting or beading, the surface tension of the substrate is considered equal to or higher than that of the ink. If the ink beads up, the test is repeated with a lower-tension ink until one wets the surface properly, thus determining the substrate's effective surface tension [7].

- Key Considerations: Common test ink materials include ethanol-based (for most surfaces), formamide-based (not for PVC; toxic), and methanol-based (toxic). Results are relative and can be sensitive to environmental conditions and application timing [7].

Wettability and Contact Angle

Defining Wettability

Wettability describes the tendency of a liquid to spread over or adhere to a solid surface. It is a function of the interplay between adhesive forces (attraction between the liquid and solid) and cohesive forces (attraction within the liquid itself) [8]. When adhesive forces dominate, the liquid spreads, resulting in high wettability. When cohesive forces dominate, the liquid forms discrete beads, resulting in low wettability [8]. This property has widespread importance, from the performance of waterproof clothing and car waxes to industrial processes in coating, painting, lubrication, and medical diagnostics [8].

Contact Angle: The Quantitative Measure of Wettability

The most common method to quantify wettability is by measuring the contact angle (θ). The contact angle is defined geometrically as the angle formed between the tangent to the liquid-vapor interface and the tangent to the solid-liquid interface at the three-phase boundary point where the solid, liquid, and gas (or vapor) intersect [9].

- Low Contact Angle (<90°): Indicates high wettability. The liquid spreads readily on the surface. When water is the probe liquid, such surfaces are termed hydrophilic [8] [9].

- High Contact Angle (>90°): Indicates low wettability. The liquid resists spreading and forms distinct droplets. When water is the probe liquid, these surfaces are termed hydrophobic [8] [9].

The theoretical foundation for the contact angle is described by Young's Equation, which balances the interfacial tensions at the three-phase contact line [9]: γSV = γSL + γLV cosθY Here, γSV is the solid-vapor interfacial tension (approximated as the solid surface free energy), γSL is the solid-liquid interfacial tension, γLV is the liquid-vapor surface tension, and θY is Young's equilibrium contact angle [9].

Factors Influencing Wettability

Wettability is not an intrinsic property but is influenced by several key factors [8]:

- Surface Tension of the Liquid: Liquids with high surface tension (like pure water) tend to exhibit lower wettability on many solid surfaces. Surfactants are often added to lower the liquid's surface tension and improve wetting [8].

- Surface Free Energy of the Solid: High surface energy materials (e.g., metals, glass) are generally more wettable than low surface energy materials (e.g., plastics, polymers) [8].

- Surface Roughness: Roughness typically amplifies the inherent wetting behavior of a surface. A rough surface will be more hydrophilic if the underlying chemistry is hydrophilic and more hydrophobic if the underlying chemistry is hydrophobic [8].

Contact Angle Measurement Methods

Static (Sessile Drop) Contact Angle

This is the simplest and most common contact angle measurement [9].

- Experimental Protocol: A drop of liquid (typically water) is carefully dispensed onto the solid substrate using a syringe. The droplet is allowed to stabilize, and an image is captured using an optical tensiometer (also known as a goniometer or drop shape analyzer). Software then fits the droplet profile and calculates the contact angle based on Young's equation [9].

- Key Considerations: This method is quick and easy but provides information only for the specific location where the droplet is placed. It assumes an ideal, smooth, rigid, and chemically homogeneous surface, conditions rarely met in practice [9].

Dynamic Contact Angles

Real-world surfaces are heterogeneous, leading to a range of stable contact angles. Dynamic measurements provide a more comprehensive characterization [9].

Advancing and Receding Contact Angle (Optical Method)

- Experimental Protocol: Using an optical tensiometer, a droplet is placed on the surface, and the needle remains inside the droplet. Liquid is steadily injected to increase the droplet volume. Initially, the contact angle increases while the three-phase contact line remains pinned. Once a critical angle is reached, the baseline advances across the surface; the contact angle at this point is the Advancing Contact Angle (ACA), which represents the maximum angle in the energy range. To measure the Receding Contact Angle (RCA), liquid is slowly withdrawn from the droplet. The contact angle decreases until the baseline begins to recede; the stabilized angle is the RCA, representing the minimum angle in the energy range [9].

- Contact Angle Hysteresis: The difference between the advancing and receding contact angles (ACA - RCA) is called hysteresis. A large hysteresis value indicates significant surface heterogeneity (roughness or chemical variation) and high liquid adhesion to the surface. A perfectly homogeneous surface would theoretically have a hysteresis of 0° [9].

Dynamic Contact Angle (Wilhelmy Plate Method)

- Experimental Protocol: This force tensiometry method uses a solid sample (the "plate") of uniform shape and known perimeter. The sample is attached to a balance and immersed into the liquid at a constant rate while the wetting force is recorded (advancing cycle). The process is then reversed, withdrawing the sample to obtain the receding curve. Linear regression of the force versus immersion depth data at zero depth allows for the calculation of both the advancing and receding contact angles, provided the liquid's surface tension is known [9].

Table 2: Summary of Contact Angle Measurement Techniques

| Technique | Method | Key Outputs | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Static Sessile Drop | Optical | Single contact angle value | Simple & fast quality check; limited surface info [9] |

| Advancing/Receding (Optical) | Optical | Advancing Angle (ACA), Receding Angle (RCA), Hysteresis | Surface heterogeneity, reproducible angles, drop mobility [9] |

| Wilhelmy Plate | Force Tensiometry | Advancing & Receding Angles from force curves | Average wettability along sample perimeter; requires uniform sample [9] |

The Interrelationship of Concepts

Surface tension, surface energy, and wettability are intrinsically linked through Young's equation. The contact angle is the most readily measurable parameter that reflects the balance between the surface energy of the solid (γSV) and the surface tension of the liquid (γLV). In practical terms, achieving good wettability (low contact angle) typically requires that the surface energy of the solid be significantly higher than the surface tension of the liquid. This principle guides countless industrial processes, such as the plasma treatment of low-energy polymers to increase their surface energy and improve the adhesion of paints, coatings, and inks [8]. Similarly, the formulation of water-based drugs or inks often involves adding surfactants to lower the liquid's surface tension, enabling it to wet target surfaces effectively [8] [7].

Diagram 1: The interrelationship between surface tension, surface energy, and contact angle in wettability analysis.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Key Research Reagents and Materials for Surface Science Experiments

| Item | Function/Application |

|---|---|

| Platinum Ring/Plate | Probe for force tensiometry (Du Noüy, Wilhelmy); platinum is used for its inertness and ease of cleaning to ensure complete wetting [10]. |

| Optical Tensiometer (Goniometer) | Instrument for capturing and analyzing droplet shape (sessile drop, pendant drop) to determine contact angle and surface tension [10] [9]. |

| High-Precision Syringe & Needle | For dispensing consistent, pendant, or sessile droplets of controlled volume for optical analysis [10] [9]. |

| Surface Tension Test Inks | Pre-formulated inks with known surface tension for quick, semi-quantitative assessment of substrate wettability in industrial QC [7]. |

| Surfactants | Chemical agents added to a liquid to reduce its surface tension, thereby improving its spreading and wetting characteristics on solid surfaces [8]. |

| Reference Liquids (Diodomethane, Water) | Liquids with known surface tension values used in contact angle measurements to calculate the surface free energy of a solid substrate. |

Diagram 2: A workflow for selecting and applying key measurement techniques in surface science.

Surface science is the study of physical and chemical phenomena that occur at the interface of two phases, such as solid-gas, solid-liquid, or liquid-gas boundaries [11] [12]. In pharmaceutical development, the surface properties of active pharmaceutical ingredients (APIs) and excipients fundamentally determine critical quality attributes including solubility, stability, and ultimately, bioavailability [13]. Atoms and molecules at surfaces exhibit distinct behaviors compared to those in the bulk material due to their reduced coordination number and higher energy state, leading to unique reactivity and physical properties [11]. This technical guide explores the fundamental principles of surface science and their direct application to pharmaceutical quality, providing methodologies for characterizing and optimizing surface properties to enhance drug product performance.

The high surface energy of materials drives phenomena such as adsorption and surface reconstruction, which can be harnessed to improve drug formulations [11]. For solid dosage forms, the solid-liquid interface between drug particles and gastrointestinal fluids governs dissolution, the critical first step in drug absorption. Surface engineering approaches, particularly nanotechnology, have emerged as powerful strategies to address poor solubility, a prevalent challenge in modern drug development [13]. By systematically understanding and manipulating surface properties, researchers can design more effective and reliable pharmaceutical products with predictable performance across diverse patient populations.

Fundamental Surface Properties and Their Measurement

Key Surface Properties Affecting Pharmaceutical Quality

Surface energy represents the excess energy at a material's surface compared to its bulk, originating from the reduced coordination of surface atoms and the presence of dangling bonds [11]. This property is a primary determinant of thermodynamic stability, with higher surface energy indicating greater reactivity and driving forces for adsorption. In pharmaceuticals, high surface energy promotes wetting and dissolution but may also increase instability by facilitating unwanted chemical reactions or physical transformations.

Surface area directly influences dissolution rates through its relationship to the contact area between solid and liquid phases. Nanotechnology approaches specifically increase surface area to enhance solubility, as demonstrated by the improved bioavailability of poorly soluble drugs like Felodipine, Ketoprofen, and Ibuprofen when incorporated into high-surface-area metal-organic frameworks (MOFs) [13].

Surface charge develops at solid-liquid interfaces through ionization of surface groups or adsorption of ions, creating an electrical double layer that affects particle aggregation, stability, and interactions with biological membranes. This property becomes particularly important in physiological environments where varying pH conditions influence ionization states and subsequent solubility [13].

Surface morphology encompasses the atomic-level structure and topography of surfaces, including features such as steps, kinks, and vacancies that significantly impact reactivity [11]. Surface reconstructions and relaxations occur to minimize surface energy, resulting in different structures than the bulk material that can influence adsorption behavior and dissolution kinetics.

Analytical Techniques for Surface Characterization

Table 1: Core Techniques for Pharmaceutical Surface Characterization

| Technique | Measured Properties | Pharmaceutical Applications | Information Depth |

|---|---|---|---|

| Atomic Force Microscopy (AFM) | Surface topography, roughness, mechanical properties | Mapping nanoscale surface features, adhesion forces | Top few atomic layers |

| X-ray Photoelectron Spectroscopy (XPS) | Surface elemental composition, chemical states | Detecting surface contaminants, coating uniformity | 1-10 nm |

| Surface-Enhanced Raman Spectroscopy (SERS) | Molecular vibrations, chemical identification | Trace analysis, adsorption studies, surface reactivity | Single molecular layer |

| Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM) | Surface morphology, microstructure | Particle shape, size distribution, surface defects | Surface region |

| Low-Energy Electron Diffraction (LEED) | Surface crystal structure, reconstruction | Assessing surface order and atomic arrangement | Topmost atomic layer |

Quantitative analytical surface-enhanced Raman spectroscopy (SERS) has emerged as a particularly powerful technique for pharmaceutical applications due to its high sensitivity, molecular specificity, and speed of analysis [14]. The essential components of a quantitative SERS experiment include: (1) the enhancing substrate material, typically aggregated Ag or Au colloids; (2) the Raman instrument; and (3) the processed data used to establish calibration curves [14]. SERS quantitation requires careful attention to sources of variance associated with the instrument, enhancing substrate, and sample matrix, many of which can be minimized through internal standards [14].

Connecting Surface Properties to Critical Quality Attributes

Surface Properties and Drug Solubility

Drug solubility represents a fundamental determinant of bioavailability, particularly for Biopharmaceutics Classification System (BCS) Class II compounds with poor solubility but good permeability [13]. The dissolution rate of solid dosage forms follows the Noyes-Whitney equation, where increased surface area directly enhances dissolution velocity. Nanotechnology approaches exploit this relationship by reducing particle size to increase surface area-to-volume ratios, thereby improving solubility and absorption.

Surface energy influences wetting behavior, a critical factor in dissolution, as described by Young's equation relating contact angle to surface tensions [11]. High-energy surfaces promote spreading of gastrointestinal fluids across drug particles, facilitating dissolution. Research has demonstrated that incorporating poorly soluble drugs like Apixaban with Quercetin in cocrystal form significantly improves solubility and absorption by modifying surface properties and interaction with dissolution media [13].

Physiological variability in gastrointestinal pH creates particular challenges for drugs with pH-dependent solubility. Weakly basic drugs demonstrate higher solubility in acidic stomach environments, while weak acids dissolve more readily in the neutral-small intestine [13]. Surface engineering approaches, including nanomaterial-based systems, can mitigate this variability by maintaining enhanced solubility across physiological pH ranges.

Surface Properties and Stability

Chemical stability at surfaces differs substantially from bulk behavior due to the higher energy state and increased exposure to environmental factors. Surface atoms catalyze degradation reactions in susceptible compounds, necessitating protective strategies. Surface segregation phenomena, where impurities or specific components concentrate at surfaces to lower overall energy, can accelerate degradation or alter release profiles in solid dispersions and multi-component systems [11].

Physical stability encompasses changes in crystalline form, particle aggregation, and surface morphology over time. Surface reconstructions occur to minimize surface energy, potentially altering dissolution characteristics and bioavailability [11]. These transitions are particularly problematic for metastable polymorphs intentionally selected for their enhanced solubility, as they may revert to more stable, less soluble forms during storage.

Surface engineering approaches enhance stability through functionalization, coating, or composite formation. For example, inorganic nano-drug delivery platforms improve therapeutic performance at tumor sites while maintaining stability during circulation [13]. Similarly, functionalized magnetic nanoparticles offer controlled drug release in inflammation treatment while protecting labile compounds from degradation [13].

Surface Properties and Bioavailability

Bioavailability integrates solubility, stability, and absorption processes to determine the fraction of administered drug that reaches systemic circulation. Surface properties influence each component, making them critical to overall product performance. The adsorption of drug molecules to surfaces affects release kinetics, with the strength of interaction determining whether compounds remain bound or freely diffuse toward absorption sites.

Targeted delivery systems exploit surface interactions to achieve site-specific drug release. Magnetic nanoparticles (MNPs) can be engineered with specific surface characteristics and magnetic properties that allow precise targeting using external magnetic fields, directing drugs to specific sites like tumors or inflamed tissues [13]. This approach enhances efficacy while minimizing systemic exposure and side effects.

Surface modifications also improve bioavailability by enhancing membrane permeability and circumventing efflux transporters. The surface of nanoparticles can be functionalized with various ligands to improve their interaction with biological membranes, enhancing cellular uptake and absorption [13]. These strategies are particularly valuable for compounds with poor permeability or those subject to extensive pre-systemic metabolism.

Surface-Property-Quality Relationship

Surface Engineering Approaches in Pharmaceutical Development

Nanotechnology-Based Surface Modifications

Nanotechnology represents a transformative approach to surface engineering, enabling manipulation of materials at molecular and atomic levels to enhance drug solubility and delivery [13]. Magnetic nanoparticles (MNPs) exemplify this strategy, offering controllable size, surface characteristics, and magnetic properties that enable precise targeting and controlled drug release [13]. These systems navigate complex physiological environments like the GI tract, overcoming variability in pH levels that traditionally affect drug solubility and absorption.

Metal-organic frameworks (MOFs) provide high surface areas and tunable surface chemistry that significantly enhance drug loading and dissolution. Studies demonstrate that incorporating BCS Class II drugs like Felodipine, Ketoprofen, and Ibuprofen into MOFs substantially improves their solubility and therapeutic efficacy [13]. Similarly, nano- and microemulsions create optimized interfacial environments for poorly soluble drugs, addressing variability in absorption and bioavailability for CNS-targeting agents [13].

Surface functionalization of nanoparticles with specific ligands enhances interactions with biological systems while protecting payloads. For example, functionalized magnetic nanoparticles provide controlled drug release in inflammation treatment, targeting affected areas while minimizing impact on healthy tissues [13]. These targeted approaches not only enhance efficacy but also reduce the systemic side effects associated with conventional therapies.

Analytical Surface Engineering Methodologies

Quantitative surface analysis requires rigorous methodologies to establish reliable structure-property relationships. Surface-enhanced Raman spectroscopy (SERS) has evolved as a powerful quantitative technique when properly implemented [14]. The precision of SERS measurements should be expressed as the relative standard deviation (RSD) of signal intensity across multiple experiments, with careful attention to the standard deviation in recovered concentration for meaningful analytical comparisons [14].

Internal standardization proves critical for robust quantitative surface analysis, minimizing variances associated with instruments, enhancing substrates, and sample matrices [14]. Since plasmonic enhancement falls off steeply with distance, substrate-analyte interactions fundamentally determine successful SERS detection and quantification [14]. Understanding these relationships enables rational experimental design for reliable surface-based measurements.

Advanced characterization techniques provide insights into surface phenomena at unprecedented resolution. Scanning probe microscopy, X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS), surface X-ray scattering, and surface-enhanced Raman spectroscopy enable detailed investigation of surface processes critical to pharmaceutical performance [12]. These methods facilitate understanding of surface diffusion, reconstruction, phonons and plasmons, epitaxy, and electron emission and tunneling phenomena [12].

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Quantitative SERS Protocol for Surface Analysis

Principle: Surface-enhanced Raman spectroscopy exploits plasmonic and chemical properties of nanomaterials to dramatically amplify Raman scattering from molecules on their surfaces, enabling highly sensitive quantitative analysis [14].

Materials and Equipment:

- Raman spectrometer with appropriate laser wavelength (typically 532, 633, or 785 nm)

- Enhancing substrate (aggregated Ag or Au colloids provide robust starting points)

- Internal standard compounds (isotopically labeled analogs or structurally similar compounds)

- Sample preparation equipment (micropipettes, vortex mixer, centrifuge)

Procedure:

- Substrate Preparation: Aggregate colloidal solutions using appropriate electrolytes (e.g., NaCl, MgSO₄) to optimize enhancing properties. Consistency in aggregation state is critical for reproducible quantification.

- Sample Preparation: Mix analyte solutions with internal standards before addition to enhancing substrates. Maintain consistent mixing protocols and incubation times.

- Data Acquisition: Collect spectra from multiple spots across the substrate to account for heterogeneity. Typical acquisition times range from 1-10 seconds with 5-20 accumulations.

- Data Processing: Calculate signal height of relevant bands rather than area to minimize interference from adjacent peaks. Plot SERS intensity against concentration to generate calibration curves.

- Quantification: Apply Langmuir or other appropriate isotherm models to account for finite enhancing sites and surface saturation effects. Use linear ranges of calibration curves for quantification.

Critical Considerations:

- SERS calibration curves typically show linear response at low concentrations followed by plateau at higher concentrations due to surface saturation [14]

- Precision should be reported as RSD of recovered concentration, not just signal intensity

- Substrate-analyte interactions critically influence results due to steep distance dependence of plasmonic enhancement [14]

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Surface Science Studies

| Reagent/Material | Function in Surface Science | Application Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Gold & Silver Colloids | Plasmonic enhancing substrates for SERS | Quantitative detection of low-concentration analytes |

| Functionalized Magnetic Nanoparticles | Targeted drug delivery platforms | Site-specific drug release, inflammation treatment |

| Metal-Organic Frameworks (MOFs) | High-surface-area carriers | Solubility enhancement for BCS Class II drugs |

| Internal Standard Compounds | Reference materials for quantification | Improving precision in quantitative SERS |

| Surface Modification Ligands | Alter surface chemistry and functionality | Controlling drug release profiles, enhancing stability |

Protocol for Evaluating pH-Dependent Solubility

Principle: This protocol characterizes drug solubility across physiologically relevant pH ranges to predict in vivo performance and guide formulation strategies.

Materials and Equipment:

- Buffers covering pH 1.2 (simulated gastric fluid) to 7.4 (simulated intestinal fluid)

- Shaking water bath maintained at 37°C

- HPLC system with UV detection or alternative quantification method

- Centrifuge with temperature control

- pH meter with appropriate electrodes

Procedure:

- Buffer Preparation: Prepare standard buffers covering physiologically relevant range (pH 1.2, 4.5, 6.8, 7.4) with appropriate ionic strength.

- Equilibrium Solubility Determination: Add excess drug to each buffer and agitate in shaking water bath at 37°C for 24-72 hours until equilibrium reached.

- Sample Processing: Centrifuge samples at appropriate speed to separate undissolved material, collect supernatant without disturbing precipitate.

- Analysis: Quantify drug concentration in supernatant using validated analytical method (e.g., HPLC-UV). Ensure dilution within linear range of calibration curve.

- Data Interpretation: Plot solubility versus pH to identify potential challenges and opportunities for formulation intervention.

Critical Considerations:

- For weak acids and bases, solubility will show characteristic pH dependence according to Henderson-Hasselbalch relationships

- Surface modifications can alter pH-solubility profiles, enabling more consistent performance across physiological environments

- Nano-formulations may demonstrate different pH-solubility relationships than conventional forms due to surface effects

pH-Dependent Solubility Protocol

Emerging Trends and Future Perspectives

The field of surface science in pharmaceuticals continues to evolve, with several emerging trends shaping future research directions. Advanced analytical techniques are enabling more quantitative surface studies, addressing historical limitations in truly quantitative surface science [15]. The convergence of theory and experiment in surface dynamics represents a particularly promising development, facilitating deeper understanding of fundamental processes [16].

Digital SERS and AI-assisted data processing methodologies are overcoming traditional limitations in quantitative analysis, enhancing precision and enabling analysis of complex real-life samples [14]. These approaches leverage sophisticated algorithms to extract meaningful information from complex spectral data, improving quantification accuracy and expanding applications to challenging matrices like biological fluids.

Multifunctional SERS substrates represent another frontier, integrating sensing, separation, and enrichment capabilities to address complex analytical challenges [14]. These smart substrates enable comprehensive analysis of real-world samples with minimal pretreatment, potentially transitioning SERS from specialized research tool to routine analytical technique.

Personalized medicine approaches increasingly leverage surface engineering to address biological variability in drug response [13]. By designing surface-modified formulations that maintain performance across diverse physiological conditions, researchers can develop more consistently effective treatments tailored to individual patient characteristics. This strategy is particularly valuable for drugs with narrow therapeutic windows or high inter-individual variability.

The growing emphasis on quantitative surface analysis underscores the transition from purely descriptive studies to predictive science capable of guiding formulation design [14]. As characterization techniques continue advancing, particularly through developments in scanning probe microscopy, X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy, and surface X-ray scattering, researchers gain unprecedented insights into surface processes critical to pharmaceutical performance [12].

Future research priorities include developing universal therapeutic solutions capable of overcoming biological variability, fostering interdisciplinary collaborations between surface scientists and pharmaceutical developers, and leveraging advances in personalized nanomedicine to address individual patient needs [13]. These efforts will continue bridging fundamental surface science with practical pharmaceutical applications, ultimately enhancing product quality through optimized surface properties.

Essential Terminology for Pharmaceutical Surface Science

Fundamental Concepts and Definitions

Surface science is the study of physical and chemical phenomena that occur at the interface of two phases, such as solid-liquid, solid-gas, and liquid-gas interfaces [17]. In pharmaceutical applications, this translates to understanding how drug substances interact with their containers, processing equipment, and biological targets at the molecular level.

The surface region is scientifically defined as "the outermost region of a material that is chemically and/or energetically unique by virtue of being located at a boundary" [18]. This region possesses distinct properties compared to the bulk material beneath it, which profoundly impacts pharmaceutical performance.

Key Surface Properties in Pharmaceuticals

Table 1: Fundamental Surface Science Terminology and Pharmaceutical Relevance

| Term | Scientific Definition | Pharmaceutical Relevance |

|---|---|---|

| Surface Energy | The excess energy at the surface of a material compared to the bulk; originates from reduced coordination of surface atoms [11]. | Determines powder flow, compaction, and dissolution behavior of active pharmaceutical ingredients (APIs) and excipients [18]. |

| Surface Tension | The force that acts on the surface of a liquid, aiming to minimize its surface area [19]. | Influences droplet formation in inhalers, emulsion stability, and bioavailability [20]. |

| Contact Angle | The angle between a liquid's surface and a solid surface, quantifying wettability [19]. | Predicts tablet coating performance, liquid penetration into granules, and bioadhesion [19]. |

| Adsorption | The adhesion of atoms, ions, or molecules from a gas, liquid, or dissolved solid to a surface [11]. | Affects protein binding to drug delivery devices, contamination control, and filter capacity [18]. |

| Surface Reconstruction | The rearrangement of surface atoms to minimize surface energy, resulting in a different structure than the bulk [11]. | Can alter the chemical stability and reactivity of solid dosage forms over time. |

Critical Surface Science Measurements

Contact Angle Measurement

The contact angle quantifies the wettability of a solid by a liquid, which is crucial for predicting how effectively body fluids will wet and dissolve a dosage form [19]. In practice, surfaces exhibit a range of contact angles rather than a single value.

- Advancing Contact Angle: The maximum angle measured as the liquid front moves forward over a dry surface [19].

- Receding Contact Angle: The minimum angle measured as the liquid retracts from a wet surface [19].

- Dynamic Contact Angle: The measurement of how the contact angle changes during liquid advancement or recession, providing a more holistic view of liquid-solid interaction than static measurements [19].

Standard Practice: ASTM D7334-08 specifies procedures for measuring the advancing contact angle to evaluate coating adhesion, verify surface treatments, and compare substrate performance across production batches [19].

Surface Tension Measurement

Surface tension measures the force that acts on the surface of a liquid, aiming to minimize its surface area [19]. This property is vital for processes involving rapid changes at interfaces.

- Static Surface Tension: Characterizes the equilibrium state of the liquid interface [19].

- Dynamic Surface Tension: Accounts for the kinetics of changes at the interface, which is essential for processes like droplet formation, foam behavior, and spray drying of pharmaceuticals [19].

Surface Energy Measurement

Surface energy refers to the work required to create a unit area of a new surface [19]. Matching surface energies between drug and excipient materials ensures proper bonding and consistent drug release in composite formulations [19].

Experimental Protocols for Surface Characterization

General Guidelines for Reporting Experimental Protocols

Comprehensive reporting of experimental protocols is fundamental for reproducibility. A guideline developed from analysis of over 500 protocols recommends 17 essential data elements that should be included [21]:

- Protocol name and objective

- Required materials and their specifications

- Required equipment and software

- Step-by-step instructions

- Timing information

- Sequencing of steps

- Safety precautions

- Termination criteria

- Troubleshooting instructions

- Expected outcomes

- Criteria for success

- Storage instructions for reagents and samples

- Disposal instructions

- Preparation instructions for reagents and equipment

- Hints for precise execution

- Calculation methods

- References to prior literature

Workflow for Surface Characterization of Pharmaceutical Powders

The following diagram illustrates a generalized experimental workflow for characterizing the surface properties of pharmaceutical powders, incorporating key measurement techniques:

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Pharmaceutical Surface Science Experiments

| Item | Function | Application Example |

|---|---|---|

| Reference Liquids | High-purity liquids with known surface tension for instrument calibration and surface energy calculations. | Used in contact angle measurements to determine surface energy of tablet coatings [19]. |

| Self-Assembled Monolayer (SAM) Kits | Organic compounds that create dense monolayers presenting defined surface functionalities. | Engineering surfaces with precise chemical properties to study cell-material interactions [18]. |

| Pharmaceutical Powders | Well-characterized active pharmaceutical ingredients (APIs) and excipients with known properties. | Fundamental materials for studying powder surface properties and their impact on formulation [18]. |

| Surface Tension Standards | Certified reference materials with precisely known surface tension values. | Calibrating tensiometers for accurate dynamic surface tension measurements of aerosol formulations [19]. |

| Contact Angle Calibration Standards | Surfaces with known, stable contact angles for instrument validation. | Verifying measurement system performance before testing proprietary pharmaceutical samples [19]. |

Pharmaceutical Applications of Surface Science

Real-World Applications in Drug Development

Surface science principles find critical application throughout pharmaceutical development and manufacturing:

Oral Drug Formulation: Measuring the wetting angle of drug solutions on various excipient surfaces identifies materials that promote optimal wetting and dissolution. A lower contact angle indicates better wetting and faster dissolution, leading to improved bioavailability [19].

Inhalable Medications: Surface tension measurement of liquid formulations used in aerosols enables optimization of spray characteristics to achieve desired droplet size and uniformity, ensuring medication reaches the target site within the lungs [19].

Transdermal Drug Delivery: Meticulous measurement of surface energy ensures that patch components (drug reservoir and adhesive material) have matching surface energies for proper bonding and consistent drug release [19].

Manufacturing Contamination Control: Measuring the sliding angle of liquids used in manufacturing helps identify surfaces less likely to allow liquid adhesion, enabling design of equipment that is easy to clean and resistant to contamination [19].

Impact of Surface Properties on Product Performance

Surface properties directly influence multiple critical quality attributes of pharmaceutical products:

Chemical Activity and Bioavailability: The chemical activity, adsorption, dissolution, and bioavailability of a drug may depend on the surface properties of the molecule [20].

Processing Behavior: Surface properties of powders significantly impact processes like liquid penetration into tablets and granules, powder spreading in liquids, phase separation, and emulsion formation and stability [19].

Biological Response: In biomaterials, surface energy and wettability are primary determinants of biological response, with most anchorage-dependent mammalian cells strongly favoring hydrophilic surfaces [18].

Practical Techniques and Applications: Measuring and Manipulating Surfaces in the Lab

Surface characterization is a powerful foundation tool for investigating and understanding the properties and functions of materials, enabling researchers to establish critical structure-activity relationships [22]. These techniques provide invaluable insights into surface composition, structure, and behavior at the micro-nano to atomic scale, forming an essential component of research in chemistry, materials science, and drug development [23]. For beginners in surface science research, mastering these core measurement techniques is fundamental to designing effective experiments and interpreting data accurately.

This guide serves as an introduction to the principal characterization methods, organized for clarity and practical application. We present these technologies in coordinated groups to provide comprehensive references for researchers, covering both physical and chemical aspects of functional materials including morphologies, pore structures, crystal structures, chemical compositions, oxidation states, coordination, and electron structures [22]. The techniques discussed form the basis for advanced research and establish technical foundations for the discovery of novel functional materials.

Classification of Characterization Techniques

Surface characterization techniques are broadly classified into three main categories based on their operational principles and the information they provide: spectroscopic techniques, microscopic techniques, and probe-based methods [23]. Each category offers unique capabilities for analyzing different surface properties, from elemental composition to topographical features at the atomic scale.

The table below summarizes the major technique categories and their primary applications:

Table 1: Classification of Surface Characterization Techniques

| Technique Category | Primary Applications | Information Obtained | Spatial Resolution |

|---|---|---|---|

| Spectroscopic Techniques (XPS, AES, SIMS) | Chemical composition, electronic structure, oxidation states | Elemental identification, chemical bonding, depth profiling | ~µm for XPS/AES; sub-µm for SIMS |

| Microscopic Techniques (SEM, TEM) | Surface morphology, crystal structure, defect analysis | Topography, crystallography, elemental mapping | ~nm for SEM; atomic-scale for TEM |

| Probe-Based Techniques (STM, AFM) | Surface structure, local electronic properties, mechanical properties | Atomic-scale topography, surface potential, friction | Atomic resolution |

| Diffraction Techniques (XRD) | Crystal structure, phase identification, strain analysis | Crystalline phases, lattice parameters, texture | N/A (bulk technique) |

Spectroscopic Techniques

Spectroscopic techniques analyze the interactions between energy and matter to determine surface composition and chemical states:

X-ray Photoelectron Spectroscopy (XPS): Utilizes the photoelectric effect, where X-rays excite core-level electrons, and the kinetic energy of emitted photoelectrons is measured to determine binding energy and chemical state of surface atoms [23]. XPS provides quantitative elemental composition and chemical state information with a sampling depth of a few nanometers [23]. This technique is particularly valuable for determining oxidation states and surface functionalization.

Auger Electron Spectroscopy (AES): Relies on the Auger electron emission process, where an electron is ejected from an inner shell, and subsequent relaxation of an outer-shell electron results in emission of an Auger electron with element-specific kinetic energy [23]. AES is particularly useful for elemental mapping with good spatial resolution and for analyzing conductive materials.

Secondary Ion Mass Spectrometry (SIMS): Uses a focused ion beam (typically Cs⁺ or O⁻) to sputter surface atoms, analyzing ejected secondary ions based on mass-to-charge ratio [23]. SIMS offers exceptional sensitivity for trace element detection and depth profiling capabilities. Dynamic SIMS allows for depth profiling by continuously sputtering the surface while monitoring secondary ion intensity.

Microscopic Techniques

Microscopic techniques provide high-resolution imaging capabilities for visualizing surface features across multiple length scales:

Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM): Employs a focused electron beam to scan surfaces, detecting secondary electrons, backscattered electrons, and X-rays to form images and provide compositional information [23]. Modern SEM can achieve resolution in the nanometer range and can operate in various imaging modes to highlight different surface features and chemical contrasts.

Transmission Electron Microscopy (TEM): Uses a high-energy electron beam (typically 100-300 keV) that transmits through thin samples, with electron-sample interactions forming images and diffraction patterns [23]. High-resolution TEM (HRTEM) can resolve individual atomic columns, while scanning TEM (STEM) allows for chemical mapping and spectroscopy at the atomic scale. TEM requires extensive sample preparation to create electron-transparent specimens.

Probe-Based Techniques

Probe-based methods enable the study of surface properties at the atomic scale through precise physical interactions:

Scanning Tunneling Microscopy (STM): Relies on the quantum tunneling effect, where a sharp conductive tip is brought close to the surface, and the resulting tunneling current is measured as a function of tip position to map surface topography and local density of states [23]. STM can achieve true atomic resolution but requires conductive samples.

Atomic Force Microscopy (AFM): Uses a sharp tip on a cantilever to measure force interactions between tip and surface, providing topographic and mechanical property information at the nanoscale [23]. AFM can operate in various modes (contact, non-contact, tapping) to suit different sample properties and measurement requirements, and can analyze both conductive and insulating surfaces.

Technical Specifications and Data Comparison

Understanding the fundamental parameters of each characterization technique is essential for proper selection and experimental design. The following table provides quantitative comparisons of key technical aspects across major characterization methods:

Table 2: Technical Specifications of Major Characterization Techniques

| Technique | Energy Range/Probe Type | Primary Beam → Signal Detected | Sampling Depth | Detection Limits |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| XPS | >1 keV (X-rays) | Photon → Electron | 1-10 nm | 0.1-1 at% |

| AES | 500 eV-10 keV (Electrons) | Electron → Electron | 2-10 nm | 0.1-1 at% |

| SIMS | 1-15 keV (Ions) | Ion → Ion | 1-2 nm (static); depth profiling (dynamic) | ppm-ppb |

| SEM | 0.3-30 keV (Electrons) | Electron → Electron | 1 µm - 1 mm (varies with mode) | 1 at% (with EDS) |

| TEM | 100-400 keV (Electrons) | Electron → Electron | Sample thickness <100 nm | Single atom |

| AFM | Mechanical probe | Force → Deflection | Atomic layer | Atomic resolution |

| XRD | >1 keV (X-rays) | Photon → X-ray | µm to mm (bulk technique) | 1-5 wt% |

The surface sensitivity of electron beam techniques is governed by processes that alter the speed (inelastic scattering, energy loss) or direction (elastic scattering, deflection) of the probing particle [24]. The sampling depth is determined by the mean free path of electrons or other signal carriers in the material, which depends on their energy and the material's composition.

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

XPS Analysis Protocol

Sample Preparation:

- Conduct solid samples as thin films or small pieces (typically 1×1 cm)

- Ensure surfaces are clean and free from contaminants

- Use appropriate mounting methods (clips, adhesive tapes) for electrical contact

- Handle air-sensitive samples in glove boxes or transfer under inert gas

Data Acquisition:

- Place sample in ultra-high vacuum chamber (typically <10⁻⁸ mbar)

- Acquire survey spectrum to identify all elements present

- Collect high-resolution regional scans for elements of interest

- Use appropriate pass energy (20-80 eV for high resolution; 100-200 eV for survey)

- Include charge compensation for insulating samples using low-energy electron flood gun

Data Analysis:

- Apply charge referencing to adventitious carbon (C 1s at 284.8 eV)

- Perform background subtraction (Shirley or Tougaard background)

- Use peak fitting with appropriate constraints (peak position, FWHM, area ratios)

- Quantify using relative sensitivity factors provided by instrument manufacturer

SEM Imaging Protocol

Sample Preparation:

- Mount samples on appropriate stubs using conductive adhesive