Surface Science Sample Preparation: Foundational Principles, Advanced Methods, and Biomedical Applications

This comprehensive guide details the critical role of sample preparation in surface science, a pivotal stage that determines the success of subsequent analytical techniques.

Surface Science Sample Preparation: Foundational Principles, Advanced Methods, and Biomedical Applications

Abstract

This comprehensive guide details the critical role of sample preparation in surface science, a pivotal stage that determines the success of subsequent analytical techniques. Tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, the article explores fundamental principles, from contamination control to the selection of mounting and sectioning techniques. It provides a deep dive into both traditional and next-generation methodological approaches, including ion milling and specialized protocols for challenging samples like proteins and powders. The content further addresses common troubleshooting scenarios and optimization strategies, and concludes with a rigorous framework for method validation, quality control, and comparative technique analysis to ensure data reliability and precision in biomedical and clinical research.

Core Principles and the Critical Importance of Surface Preparation

Why Sample Preparation is a Pivotal Stage in the Analytical Process

Sample preparation is the foundational step in the analytical process where raw samples are processed into a state suitable for analysis. In surface science research, this step is not merely preliminary; it is pivotal to the accuracy, reliability, and success of the entire analytical endeavor [1]. Effective sample preparation ensures that the analyzed sample truly represents the substance being studied, free from contamination or loss of analytes [1]. For surface-bound proteins and other delicate interfaces, proper preparation is the key to preserving molecular structure and obtaining meaningful data from sophisticated surface analysis techniques like X-ray Photoelectron Spectroscopy (XPS) and Time-of-Flight Secondary Ion Mass Spectrometry (ToF-SIMS) [2].

This guide provides troubleshooting and best practices to help researchers navigate the specific challenges of sample preparation within surface science.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: Why is sample preparation especially critical for surface analysis techniques like XPS and ToF-SIMS? Surface analysis techniques probe only the outermost layers of a material. The presence of contaminants, uneven surfaces, or improperly bound molecules can drastically skew results [2] [3]. Proper sample preparation ensures the surface presented for analysis accurately reflects the intended experimental condition.

Q2: What are the most common consequences of poor sample preparation? The most frequent issues include:

- Inaccurate Quantification: Contamination or incomplete recovery of analytes leads to incorrect concentration measurements [1].

- Poor Reproducibility: Inconsistent preparation methods make it impossible to replicate experiments or validate results [4] [1].

- Analyte Degradation: Harsh or inappropriate preparation can degrade sensitive molecules, such as proteins or drugs, altering the sample's true nature [4] [1].

- Instrument Damage and Contamination: Particulate matter or incompatible solvents can clog or damage sensitive instrumentation [4].

Q3: For surface-bound protein studies, what preparation aspects require the most attention? Controlling the attachment chemistry (e.g., charge-charge, covalent bonding) and the orientation and conformation of the protein on the surface is paramount [2]. Any deviation during preparation, such as unintentional exposure to air-water interfaces, can denature proteins and invalidate the study [2].

Q4: How can I improve the consistency of my sample preparation? Implement Standard Operating Procedures (SOPs), use calibrated instruments, and conduct regular training [5]. Automation, where feasible, can also significantly reduce human error and enhance throughput [6].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: Incomplete or Low Analyte Recovery

This occurs when the target molecule is not fully extracted from the sample matrix or is lost during transfer.

- Potential Causes and Solutions:

- Cause: Inefficient extraction method.

- Cause: Adsorption to container walls.

- Solution: Use low-adsorption tubes and vials. In some cases, adding a carrier protein or modifying the solvent can minimize losses.

- Cause: Incomplete solubilization.

- Solution: Ensure the diluent is appropriate for your analyte. For drugs with low aqueous solubility, a mix of organic and aqueous solvents may be needed [4].

Problem: Poor Reproducibility Between Samples

This indicates a lack of consistency in the preparation steps.

- Potential Causes and Solutions:

- Cause: Inconsistent manual techniques (e.g., pipetting, weighing, transfer).

- Cause: Variable sample matrices.

- Solution: For heterogeneous samples (e.g., soil, tablets), ensure thorough homogenization and grinding before aliquoting [1].

- Cause: Uncontrolled environmental factors.

- Solution: Allow refrigerated samples to reach room temperature before opening to prevent moisture condensation, which can alter weight and composition [4].

Problem: Analyte Degradation During Preparation

The molecule of interest breaks down before analysis.

- Potential Causes and Solutions:

- Cause: Overly harsh conditions (e.g., prolonged sonication generating excess heat).

- Solution: Optimize sonication time and mitigate heat by adding ice to the bath [4]. Explore gentler extraction methods like shaking or vortexing.

- Cause: Exposure to light, oxygen, or improper pH.

- Solution: Use amber vials for light-sensitive compounds [4]. Prepare samples in an inert atmosphere and use buffers to maintain a stable pH.

- Cause: Enzymatic or chemical activity in the sample.

- Solution: Use enzyme inhibitors or perform preparations at lower temperatures to quench ongoing reactions.

- Cause: Overly harsh conditions (e.g., prolonged sonication generating excess heat).

Essential Materials and Reagents

The table below lists key reagents and materials used in sample preparation for surface science and pharmaceutical analysis.

| Item | Function |

|---|---|

| C18 Sorbents (SPE) | Reversed-phase solid-phase extraction; retains non-polar analytes from aqueous solutions for cleanup and concentration [5]. |

| QuEChERS Kits | "Quick, Easy, Cheap, Effective, Rugged, and Safe" method for extracting pesticides and other contaminants from complex food matrices [5]. |

| Volumetric Flasks (Class A) | Provides highly accurate volume measurement for quantitative preparation of standard and sample solutions [4]. |

| Syringe Filters (0.45/0.2 µm) | Removes particulate matter from liquid samples prior to HPLC or LC-MS analysis to protect the instrumentation [4]. |

| Microbalance | Accurately weighs very small quantities (< 20 mg) of reference standards or high-potency APIs where limited availability is an issue [4]. |

| Nitrogen Evaporator (e.g., MULTIVAP) | Gently and efficiently concentrates analytes by evaporating solvent under a stream of nitrogen, improving detection sensitivity [1]. |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Sample Preparation for a Drug Substance (DS) - "Dilute and Shoot"

This protocol is used for the analysis of pure active pharmaceutical ingredients (APIs) [4].

1. Weighing: * Warm a refrigerated API sample to room temperature before opening to prevent moisture condensation [4]. * Tare a folded weighing paper or small weighing boat on a five-place analytical balance. * Accurately weigh 25-50 mg of the DS powder. Speedy handling is paramount for hygroscopic APIs [4].

2. Solubilization: * Quantitatively transfer the powder to an appropriately sized Class A volumetric flask using a funnel. Rinse the paper/boat with diluent to ensure complete transfer. * Fill the flask about halfway with the predetermined diluent. The diluent is chosen based on the API's solubility and stability, often an acidified water or a mixture of organic and aqueous solvents [4]. * Solubilize the API using an ultrasonic bath for the optimized time. Scrutinize the solution to ensure all particles are dissolved. As an alternative, use a shaker or vortex mixer for a more defined process [4].

3. Final Preparation: * Dilute to the final volume with the diluent and mix thoroughly. * Transfer an aliquot (e.g., 1.5 mL) into an HPLC vial using a disposable pipette. Use an amber vial if the solution is light-sensitive [4]. * Note: Filtration of a pure DS solution is generally discouraged, as regulatory agencies do not expect particulates in the substance [4].

Protocol 2: Sample Preparation for a Solid Oral Drug Product (DP) - "Grind, Extract, and Filter"

This protocol is used to extract the API from solid dosage forms like tablets and capsules [4].

1. Particle Size Reduction: * For potency testing, crush 10-20 tablets into a fine powder using a porcelain mortar and pestle. * For content uniformity testing, wrap a single tablet in weighing paper and crush it with a pestle.

2. Extraction: * Quantitatively transfer the powder (an amount corresponding to the average tablet weight) to a volumetric flask. * Add diluent and extract the API by sonication or shaking for the time determined during method validation [4]. For sustained-release products, a two-step extraction with an organic solvent may be needed.

3. Filtration: * Filter the extract directly into an HPLC vial through a 0.45 µm disposable syringe filter (nylon or PTFE). * Discard the first 0.5 mL of the filtrate to avoid concentration changes due to adsorption onto the filter membrane [4].

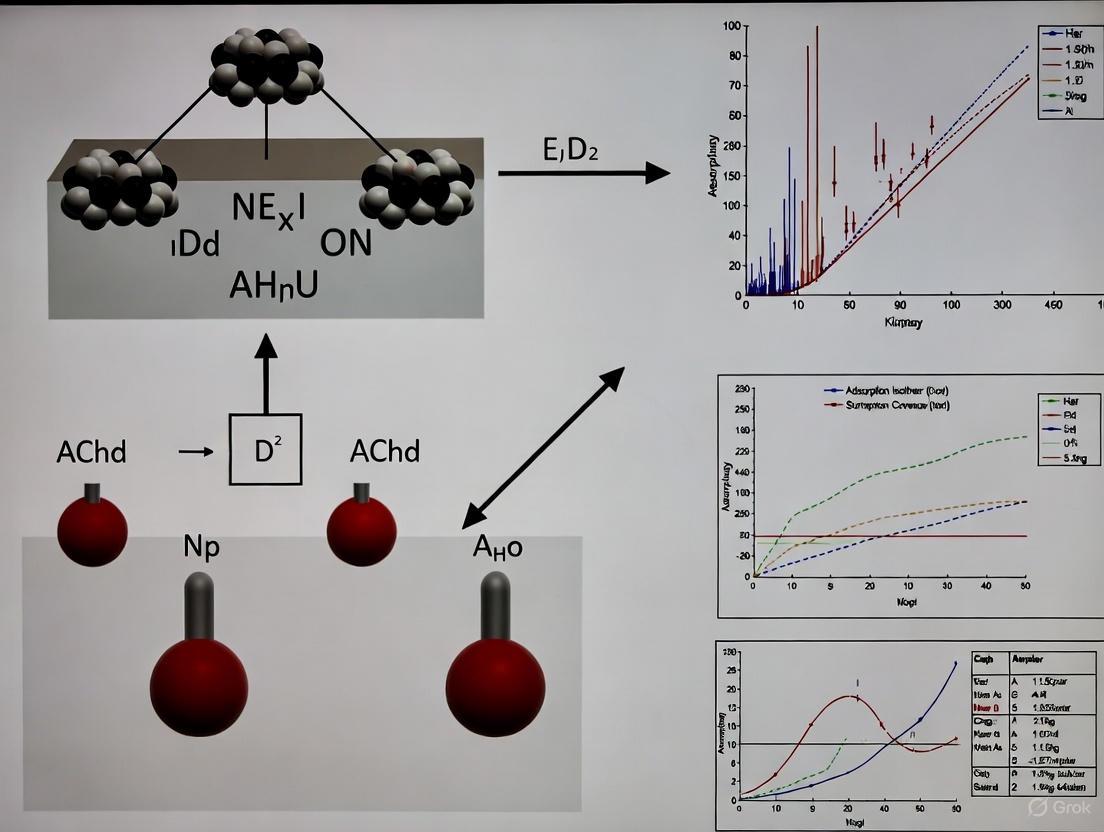

Workflow Visualization

The following diagram illustrates the decision-making process for selecting a sample preparation method based on the sample state and analytical goals.

Sample Preparation Method Selection Workflow

Surface Science Focus: Preparing Protein Samples for XPS Analysis

The diagram below outlines a generalized workflow for preparing surface-bound protein samples for analysis by techniques like XPS, highlighting critical control points.

Surface-Bound Protein Preparation Workflow

Troubleshooting Guides & FAQs

Why is there inconsistent liquid beading on my glove surfaces during solvent handling?

This inconsistency is often due to material-specific wettability and the chemical composition of the solvent.

- Problem: Some glove materials repel water effectively but may be wetted by solvents with lower surface tension, a property you are observing. The surface microstructure of the glove material dictates this interaction [7].

- Solution: Select glove materials based on the specific liquids used. Evaluate glove resistance to surface wetting for your specific solvents using a method based on standards like PN-EN ISO 6530, which calculates a non-wettability index (IR) [7]. Double-gloving with chemically resistant outer gloves can provide a secondary barrier if the primary glove is compromised [8].

How do I properly decontaminate gloves in a cleanroom without damaging them or leaving residue?

Using the wrong agent can degrade glove material and introduce contaminants.

- Problem: Traditional hand sanitizers contain emollients that leave residues on gloves, compromising sterility. Furthermore, disinfectants can degrade glove polymers, leading to microscopic holes and loss of barrier performance [9] [10].

- Solution: Use only sterile, residue-free disinfectants like 70% v/v ethanol or isopropanol, which evaporate quickly and completely [9]. Always verify compatibility between your specific glove model and decontamination agent, as performance degradation is highly dependent on the glove material and disinfectant chemistry [10].

Why does my cleanroom monitoring keep showing elevated viable particle counts?

Personnel are the primary source of contamination, accounting for up to 80% of cleanroom contamination [11].

- Problem: Elevated microbial counts can result from inadequate gowning procedures, improper glove sanitation practices, or compromised gloves. HEPA filter issues can also be a cause [12].

- Solution:

- Retrain Personnel: Reinforce rigorous gowning procedures and aseptic techniques [9] [12].

- Sanitize Gloves Correctly: Implement a validated protocol for frequency, technique, and agent used for glove disinfection [9].

- Inspect Equipment: Check HEPA filters for clogs and ensure proper airflow [12].

- Monitor: Perform regular surface sampling of gloves and sleeves using contact plates to identify contamination sources [13] [12].

Experimental Protocols & Data

Detailed Methodology: Evaluating Glove Resistance to Surface Wetting

This protocol, adapted from validated research, determines how well glove materials repel different liquids, which is critical for predicting chemical exposure and contamination risk [7].

- Sample Preparation: Cut a minimum of three samples from the palm area of the glove. Prepare 100 mm diameter discs of filter paper and foil, and weigh them together with an accuracy of 0.01 g. Weigh the glove sample itself [7].

- Setup: On an inclined gutter, place the materials in the following order: foil, filter paper, and the glove sample (oriented as in the finished product). Place a collection cup under the sample's edge and attach a syringe filled with a defined volume (e.g., 2.1 mL) of the test liquid [7].

- Liquid Application: Dispense the test liquid onto the sample surface in a fine stream and measure the time [7].

- Separation and Weighing: After 3.0-3.5 seconds, lightly tap the gutter to separate drops hanging from the edge. Remove the sample and re-weigh the filter paper with foil, the collection dish, and the test sample [7].

- Calculation: Calculate the following indices [7]:

- Non-wettability Index (IR): The proportion of liquid repelled and collected in the cup.

- Absorption Index (IA): The proportion absorbed by the glove material.

- Permeability Index (IP): The proportion that penetrated through to the filter paper.

The workflow for this experiment is outlined below.

Performance Data for Glove and Solvent Compatibility

Table 1: Glove Material Performance Against Common Solvents & Disinfectants

| Glove Material | Resistance to Water (Hydrophobicity) | Resistance to Oils (Oleophobicity) | Effect of 70% Ethanol Decontamination | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nitrile | Moderate to High [7] | Moderate [7] | Minimal performance loss in most cases [10] | General-purpose; good chemical resistance [13]. |

| Natural Latex | Moderate (Rough surface can inhibit runoff) [7] | Low to Moderate [7] | Performance varies by manufacturer [10] | Can be prone to chemical attack [13]. |

| Butyl Rubber | High [7] | Data from search results is limited | Data from search results is limited | Specialized for high-grade cleanrooms [13]. |

| Vinyl | Low | Very Low | Significant performance degradation [10] | Poor chemical and disinfectant resistance; not recommended for critical work [10]. |

Table 2: Cleanroom Glove Disinfection & Monitoring Standards

| Parameter | Recommended Practice | Supporting Standard / Rationale |

|---|---|---|

| Disinfection Agent | 70% v/v Ethanol or Isopropanol [9] | Optimal antimicrobial efficacy; evaporates without residue [9]. |

| Glove Sampling (Microbial) | Contact plates (55mm) on gloved fingers [13] | EU GMP Grade B: ≤5 CFU/plate; Grade C: ≤25 CFU/plate [13]. |

| AQL (Acceptable Quality Level) | Select gloves with a low AQL score [13] | Lower AQL indicates fewer micro-holes and higher barrier protection [13]. |

| Sterility Assurance Level (SAL) | 10⁻⁶ for sterile processes [13] | Required for gloves sterilized per ISO 11137-2:2015 [13]. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Materials

Table 3: Key Reagents and Materials for Contamination Control

| Item | Function / Application |

|---|---|

| Sterile Nitrile Gloves | Primary barrier for most sample prep tasks; offers a balance of tactile sensitivity, cleanliness, and chemical resistance [13]. |

| 70% v/v Ethanol (Sterile, double-bagged) | Preferred agent for decontaminating gloved hands in cleanrooms; effective and residue-free [9]. |

| Contact Plates with Culture Media | Used for surface monitoring of gloves and workstations to quantify viable microbial contamination (CFUs) [11] [12]. |

| Optical Particle Counter | Monitors non-viable airborne particle concentrations in real-time to ensure cleanroom classification is maintained [11]. |

| Quaternary Ammonium Solution | A hospital-grade disinfectant for surfaces; compatibility with specific glove materials should be verified before use [10]. |

In surface science research, the integrity of sample preparation is paramount. The presence of surface contaminants—often invisible to the naked eye—can drastically alter experimental outcomes, leading to erroneous data and failed processes. This guide focuses on three of the most pervasive and disruptive contaminant classes: hydrocarbons, silicones, and salts. Understanding their sources, effects, and detection methods is a critical first step in ensuring the reliability of surface-sensitive analyses, from adhesion studies to the development of novel drug delivery systems.

FAQ: Understanding Surface Contaminants

What are the most common invisible surface contaminants and where do they originate?

The most frequent invisible contaminants are adventitious carbon, silicone oils, and soluble salts. Their origins are diverse and often stem from the research environment itself [14]:

- Adventitious Carbon (Hydrocarbons): This is a nearly universal contaminant, forming a thin layer of 3–8 nanometers on all surfaces exposed to air. Sources include air pollution, cleaning solvents that deposit heavy hydrocarbons, outgassing from plastics, and improper handling with bare hands or contaminated gloves [14].

- Silicones: These are commonly introduced from silicone lubricants used on equipment, door seals in ovens, adhesives on floor mats, and even from the manufacturing process of cleanroom gloves and garments. Silicone is particularly problematic due to its stubborn adherence and ability to spread easily [14] [15].

- Soluble Salts: These contaminants, such as chlorides, sulfates, and nitrates, are often found on metal substrates after exposure to service environments or transportation. They can originate from acid rain, industrial pollution, marine environments, and chemical processes. They can also be introduced via contaminated abrasive media during surface preparation [14] [16] [17].

How do these contaminants interfere with surface-sensitive experiments?

Surface contaminants can compromise research in several key ways:

- Weakened Adhesion: Contaminants like oils and silicones form a weak boundary layer, preventing coatings, paints, and adhesives from bonding directly to the substrate. This leads to peeling, delamination, and coating failure [14] [18].

- Osmotic Blistering: Soluble salts trapped beneath a coating draw water through the film via osmosis. This buildup of pressure causes blisters and under-film corrosion, leading to premature coating failure [16] [17].

- Accelerated Corrosion: Chlorides and other salts initiate and accelerate corrosion cells on metal surfaces, even when the metal is coated, which compromises the substrate's integrity [14] [16].

- Interference with Instrumentation: In techniques like Atomic Force Microscopy (AFM), hydrocarbon contamination layers can cause unstable imaging, false feedback during probe approach, and reduced resolution [14].

What are the best methods for detecting and quantifying these contaminants?

Detection requires specific techniques, as these contaminants are often not visible.

Table 1: Detection Methods for Common Surface Contaminants

| Contaminant | Detection Method | Key Output & Measurement |

|---|---|---|

| General Surface Chemistry | X-ray Photoelectron Spectroscopy (XPS/ESCA) | Quantitative elemental composition and chemical state identification; analysis depth of ~10 nm [14]. |

| Silicones & Organic Residues | Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy (FTIR) | Chemical identification of organic and polymeric materials, ideal for silicone oils and plastic residues [15] [19]. |

| Soluble Salts (Field Testing) | Bresle Patch Method (ISO 8502-6) | Adhesive patch is fixed to surface, filled with reagent water, and extracted solution is analyzed for conductivity (all salts) or specific ions [17]. |

| Soluble Salts (Field Testing) | Ion-Specific Test Strips/Kitagawa Tubes | Extraction solution is tested with color-changing indicators to measure concentration of specific ions like Chloride (Cl⁻), Sulfate (SO₄²⁻), or Nitrate (NO₃⁻) [17]. |

How can I prevent silicone contamination in my cleanroom or lab?

Preventing silicone contamination requires a proactive and documented approach [15]:

- Specify Silicone-Free Products: Source cleanroom gloves, wipers, and apparel from specialized manufacturers who can provide Certificates of Analysis (CoA) confirming products are made in a silicone-free process.

- Verify with FTIR Testing: Rely on manufacturers who use standardized test methods like IEST-RP-CC005.4 and FTIR analysis to verify the absence of silicone on a lot-by-lot basis.

- Audit Supply Chains: Build relationships with trusted suppliers and understand the materials used in their manufacturing processes, such as silicone-free lubricants for sewing needles or glove formers.

What are the acceptable threshold levels for soluble salt contamination before coating?

There is no single universal acceptance level for soluble salts; the threshold depends on the coating system, service environment, and desired service life [16].

- Coating Manufacturer Guidance: The primary source for allowable salt levels should be the technical data sheet of the coating manufacturer.

- Risk-Based Assessment: Tolerance levels can range from non-detectable to 25 or 50 µg/cm², depending on the project specification and the corrosiveness of the environment (e.g., immersion service vs. atmospheric exposure) [16] [17].

- Conductivity Limits: Some specifications may set a maximum for overall conductivity (e.g., 5 µS/cm) rather than for specific ions [17]. A risk assessment weighing the cost of salt removal against the risk of premature coating failure is essential for decision-making [16].

Troubleshooting Guides

Guide 1: Diagnosing and Remedying Coating Adhesion Failure

Problem: A coating, paint, or adhesive is peeling or blistering.

Workflow:

Diagnostic Steps:

- Visual Inspection: Determine the failure mode. Osmotic blistering (small, often liquid-filled blisters) strongly indicates soluble salt contamination [16] [17]. Widespread peeling/delamination suggests a weak boundary layer caused by hydrocarbon or silicone contamination [14] [18].

- Test for Soluble Salts: If blistering is present, use the Bresle patch method to extract soluble salts from the surface and measure the concentration with a conductivity meter or ion-specific test strips [17]. Compare results to the project specification.

- Test for Organic Contamination: For peeling, analytical techniques like XPS can definitively identify hydrocarbon and silicone layers [14]. A simple "water break test" can also indicate organic contamination; if water sheets cleanly off a surface, it is clean, but if it beads up, organic residue is likely present.

Remediation Protocols:

- For Soluble Salts: Remove salts by high-pressure water jetting or washing with clean, hot water. Proprietary chemical cleaners can enhance salt removal. Always retest the surface after cleaning to confirm contamination is below the required threshold [17].

- For Hydrocarbons/Silicones: Use appropriate solvent cleaning, chemical cleaning, or vapor degreasing. Ensure vapor degreasing baths are properly maintained to prevent the deposition of heavy hydrocarbons [14] [18]. For silicone, prevention is more effective than removal [15].

Guide 2: Addressing Particulate Contamination in Pharmaceutical Products

Problem: Visible or sub-visible particles are observed in a liquid pharmaceutical product.

Workflow:

Diagnostic Steps [19]:

- Isolate the Contaminant: In a cleanroom or laminar flow hood, filter the product through a smooth polycarbonate membrane filter to capture particulates.

- Microscopical Examination: Use a stereomicroscope and polarized light microscopy (PLM) to perform an initial characterization of the particles' morphology, color, and optical properties.

- Advanced Chemical Identification:

- Fibers & Plastics: Use FTIR for definitive chemical identification (e.g., cotton, polyester).

- Glass & Metals: Use Scanning Electron Microscopy with Energy Dispersive X-ray Spectroscopy (SEM/EDS) for morphological and elemental analysis.

- Silicone & Oils: Use FTIR to confirm the presence of silicone oil or its degraded, "stringy" residues.

Remediation and Sourcing:

- Fibers: Typically originate from cleanroom garments and wipes. Review and reinforce gowning protocols and material controls [19].

- Glass: Can be from vial fracture or "delamination," where the inner surface of the vial flakes off due to chemical incompatibility. Review vial quality and compatibility with the drug formulation [19].

- Silicone: Almost always from the silicone lubricant applied to rubber stoppers and syringe plungers. Source silicone-free components or investigate interactions between the drug and silicone [19].

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Materials for Surface Contamination Control and Analysis

| Item/Category | Function & Purpose | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Bresle Patch Kit | Field extraction of soluble salts from steel surfaces for quantitative analysis [17]. | Follow ISO 8502-6. Adhesive must seal perfectly. Use reagent-grade water for extraction. |

| Polycarbonate Membrane Filters | Isolate particulate contamination from liquid samples for microscopic analysis [19]. | Smooth surface allows for easy particle picking. Various pore sizes (e.g., 0.45 µm) for different particle loads. |

| Silicone-Free Cleanroom Gloves & Wipers | Prevent the introduction of silicone contaminants in critical environments [15]. | Require a supplier's Certificate of Analysis (CoA) confirming lot-specific FTIR testing. |

| High-Purity Reagent Water | Diluent for standards, sample preparation, and final rinsing to prevent contamination [20]. | Must meet ASTM Type I standards (18 MΩ-cm resistivity) for trace metal analysis. |

| High-Purity Acids (ICP-MS Grade) | For sample digestion, preparation, and cleaning where ultra-low elemental contamination is vital [20]. | Check the certificate of analysis for elemental contamination levels. |

| Fluoropolymer (FEP) Labware | Store and prepare high-purity standards and samples to avoid leaching of boron, sodium, or silicon from glass [20]. | Inert and suitable for a wide pH range. Avoid for storing mercury samples. |

Table 3: Quantitative Metrics for Common Surface Contaminants

| Contaminant | Typical Thickness or Concentration | Measurement Technique | Impact Level |

|---|---|---|---|

| Adventitious Carbon | 3 - 8 nm thick layer on all air-exposed materials [14]. | XPS [14] | High - Affects adhesion, wettability, and surface chemistry. |

| Soluble Salts (General) | Specification thresholds typically range from 1 - 50 µg/cm² [16] [17]. | Bresle Method + Conductivity Meter [17] | Critical - Causes osmotic blistering and under-coating corrosion. |

| Silicone Oil | Even trace amounts can form a continuous, interfering film [14]. | FTIR [15] [19] | High - Severely weakens adhesive bonding and causes product defects. |

| Abrasive Media Contamination | Max. conductivity of 1,000 µS/cm for recycled abrasive (SSPC-AB 2) [17]. | Conductivity testing of abrasive slurry [17] | Medium-High - Can re-contaminate freshly cleaned surfaces. |

Troubleshooting Common Sample Handling Issues

This section addresses frequent challenges in sample preparation for surface science and offers targeted solutions to ensure data integrity.

Table 1: Troubleshooting Common Sample Handling Problems

| Problem | Possible Cause | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| High hydrocarbon contamination (XPS) | Touching sample with bare hands, contaminated tweezers, or storage in plastic bags [21] [22]. | Always use clean polyethylene gloves and sonicate tweezers in isopropyl alcohol (IPA) before use. Store samples in clean glass vials, polystyrene Petri dishes, or new aluminum foil [21] [22]. |

| Weak or no signal in analysis | Sample surface is too rough or powder is poorly prepared, leading to scattering or unrepresentative surfaces [23]. | For powders, press into high-purity indium foil or drop-cast from a solvent onto a clean silicon wafer. For solids, use spectroscopic milling to create a flat, homogeneous surface [21] [23]. |

| Unstable or drifting baseline (SPR) | Air bubbles in the fluidic system or a contaminated buffer [24]. | Degas the buffer thoroughly before use and check the system for leaks. Use a fresh, filtered buffer solution [24]. |

| Non-specific binding (SPR) | Inadequate blocking of the sensor surface [24]. | Block the sensor surface with a suitable agent like BSA or ethanolamine before ligand immobilization [24]. |

| Sample outgassing in vacuum | Samples (e.g., some polymers, "wet" silicones) retaining solvents or water [22]. | Dry samples in a separate vacuum chamber before analysis or reduce the sample size. For some materials, cooling the sample during analysis may be an option [22]. |

| Inconsistent results between replicates | Inconsistent sample handling, improper immobilization, or unstable ligands [24]. | Standardize all handling and preparation procedures. Verify ligand stability and ensure the instrument is properly calibrated [24]. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What is the best way to handle and store samples to prevent surface contamination? The cornerstone of contamination prevention is minimal and clean contact. Always use polyethylene gloves (as other types may contain silicones) and clean tweezers that have been sonicated in isopropyl alcohol (IPA) [21] [22]. For storage and transport, use clean glass vials, polystyrene Petri dishes, or new, clean aluminum foil. You must avoid all other plastic containers, including plastic sample bags, as they are common sources of hydrocarbon contamination [21] [22].

Q2: Can aluminum foil truly be considered a sterile barrier for sensitive procedures? Yes, peer-reviewed research supports the use of food-grade aluminum foil as a sterile barrier. One study found that foil directly from the box showed minimal to no bacterial growth when tested with ATP swabs and RODAC plates over a 6-month period. When used to cover non-sterile surgical equipment, the foil-covered surfaces also showed no growth, validating its use in creating sterile fields for sensitive work like rodent surgery [25].

Q3: What are the accepted methods for preparing powdered samples for XPS analysis? There are several universally accepted methods, with the following being the most common:

- Pressing into Indium Foil: The favored method is to press the powder into a clean, high-purity indium foil [21] [22].

- Drop-Casting: The powder can be dissolved in a suitable solvent and then drop-cast onto the surface of a clean silicon wafer [21].

- Alternative Methods: If the above are not possible, powders can be sprinkled onto sticky carbon tape or pressed into a tablet for analysis, though it is best to consult with the instrument operator first [21].

Q4: How should I clean and sterilize Petri dishes for sample storage? The method depends on the material:

- Glass Petri Dishes: Sterilize by autoclaving at 121°C for 15-20 minutes. They should be wrapped in autoclave bags or aluminum foil and allowed to cool and dry completely before use [26].

- Plastic Petri Dishes: Standard polystyrene plastic dishes are typically single-use and pre-sterilized. They are not suitable for autoclaving due to their low melting point, which causes warping [26].

Q5: My samples are magnetic. Can they still be analyzed with techniques like XPS? Yes, magnetic samples can be analyzed, but they require special consideration. Instruments with magnetic immersion lenses (common in XPS) will have a slightly different experimental setup for magnetic samples, which may lead to a slightly reduced signal intensity. It is crucial to contact the instrument operator prior to analysis to discuss the options [21].

Experimental Protocols & Data

Validating Aluminum Foil as a Sterile Barrier

Objective: To experimentally validate the sterility of food-grade aluminum foil for use as a sterile barrier on non-sterile equipment in the lab.

Methodology:

- Storage: Boxes of food-grade aluminum foil are stored with the lid closed but unsealed on a shelf in a lab area to simulate practical conditions [25].

- Sampling: At designated time points (e.g., initial, day 0, 14, 28, and 6 months), investigators don sterile gloves and remove a 30 cm section of foil for testing [25].

- Testing:

- ATP Swabs: An ATP surface test swab is applied in a zigzag pattern on the foil to detect organic material. Results are reported in Relative Light Units (RLU), with a common institutional pass rate being ≤30 RLU [25].

- RODAC Plates: Trypticase Soy Agar plates are applied to the center of both the shiny and matte sides of the foil for 5 seconds to detect bacterial growth. After incubation for 72 hours at 35°C, colony-forming units (CFU) are counted. A threshold of >15 CFU/plate is considered a failure [25].

- Application Testing: After long-term storage, foil is applied to non-sterile equipment (e.g., anesthesia machine knobs). After 30 minutes, ATP and RODAC tests are repeated on the foil-covered surfaces [25].

Results: The table below summarizes typical results from a sterility validation study [25].

Table 2: Aluminum Foil Sterility Test Results Over Time

| Time Point | ATP Swab (RLU) | RODAC - Foil Front (CFU) | RODAC - Foil Back (CFU) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Initial | 0 | 0 | 2 |

| Day 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Day 14 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| 1 Month | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 6 Months | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| 6 Months (on apparatus) | 0 | 0 | 0 |

Conclusion: The data, showing minimal to no bacterial growth and no detectable ATP, support the use of food-grade aluminum foil as an effective and inexpensive sterile barrier [25].

Sample Preparation Workflow for Surface Analysis

The following diagram illustrates a logical workflow for preparing samples for surface analysis, integrating best practices to minimize contamination.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Materials

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Sample Handling

| Item | Function & Application |

|---|---|

| High-Purity Indium Foil | Provides a clean, malleable substrate for pressing powdered samples to create a flat, uniform surface for XPS and other surface analysis techniques [21] [22]. |

| Clean Silicon Wafers | Act as an ultra-clean, flat substrate for drop-casting solutions or suspensions of powders, or for depositing thin films for analysis [21]. |

| Isopropyl Alcohol (IPA) | A high-purity solvent used for cleaning tweezers, spatulas, and other utensils via sonication to remove hydrocarbon and silicone contaminants [21]. |

| Polyethylene Gloves | Preferred over other glove types as they are less likely to contain silicone-based powders, which can transfer to samples and cause surface contamination [22]. |

| Polystyrene Petri Dishes | Ideal clean containers for short-term storage and transport of samples. They are resistant to many contaminants found in other plastics [21] [26]. |

| Food-Grade Aluminum Foil | An inexpensive, readily available material that can be used as a sterile barrier for non-sterile equipment or as a clean wrapping for sample storage [21] [25]. |

| Borosilicate Glass Vials | Chemically resistant and clean containers for long-term storage of samples. They can be thoroughly cleaned and sterilized by autoclaving for reuse [27]. |

Fundamental Concepts and Common Errors

Sample preparation is a critical preliminary step in the analytical process, where raw samples are processed to a state suitable for analysis. Effective preparation isolates and concentrates target analytes while removing interfering substances, which is fundamental to ensuring accuracy, reproducibility, and sensitivity in surface science research [1]. Errors introduced at this stage can cascade, leading to significant consequences including wasted reagents, lost experimental work, and incorrect conclusions that can mislead the scientific community [28] [1].

Sample preparation errors are a recognized contributor to the reproducibility crisis in scientific research. Analyses suggest that issues with poor lab protocols, including sample prep, account for over 10% of reproducibility failures in preclinical research. When combined with problems related to subpar reagents and materials, this figure creeps toward half of all failures [28].

Troubleshooting Guide for Solid and Powder Samples

The table below summarizes frequent issues, their root causes, and practical solutions for handling solid and powder samples.

Table: Common Problems and Solutions in Solid and Powder Sample Preparation

| Problem | Primary Cause | Recommended Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Electrostatic Behavior [29] | Particle collisions during mixing/conveying; Low humidity (<25% RH); Insulative equipment (e.g., polymer hoses). | Implement comprehensive grounding; Control relative humidity (target >40% RH); Use conductive equipment liners and ionizers. |

| Powder Segregation & Irregular Dosing [29] | Electrostatic charges causing fine and coarse fractions to separate; Over-mixing. | Redesign conveying systems with smooth radii; Remove excess fines; Optimize mixing time to avoid over-charging. |

| Powder Sticking & Adhesion [29] | Strong static charges on particles causing cling to hopper/silo walls. | Condition humidity; Use conductive or polished surfaces in hoppers; Add approved flow aids (e.g., fumed silica). |

| Low Extraction Yield [30] | Traditional techniques (e.g., maceration) rely on passive diffusion, leading to long times and solvent saturation. | Employ active techniques (e.g., RSLDE) that use a pressure gradient to force compounds out; use multi-step processes like Soxhlet extraction. |

| Sample Degradation [30] | Long extraction times with heating (e.g., steam distillation) decompose thermolabile compounds. | Utilize techniques that do not require heating, such as Rapid Solid-Liquid Dynamic Extraction (RSLDE). |

| Incomplete Sample Recovery [1] | Suboptimal extraction methods or solvent choice. | Adjust techniques; optimize extraction solvent pH to enhance recovery of acidic or basic compounds. |

Troubleshooting Guide for Liquid-Solid Extraction

Liquid-solid extraction, a core sample preparation technique, involves separating compounds based on their preferential dissolution from a solid matrix into a liquid solvent. This process is also referred to as leaching or, when the goal is to remove undesired solutes, washing [31].

Table: Common Problems and Solutions in Liquid-Solid Extraction

| Problem | Primary Cause | Recommended Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Low Recovery in Solid-Phase Extraction (SPE) [32] | Sorbent polarity mismatch; insufficient eluent strength/volume; incorrect pH. | Choose sorbent with matching retention mechanism; increase organic percentage in eluent or adjust pH; increase elution volume. |

| Poor Reproducibility in SPE [32] | Cartridge bed drying out before loading; sample flow rate is too high; cartridge overload. | Re-activate and re-equilibrate cartridge before use; lower the sample loading flow rate; reduce sample amount or use a larger cartridge. |

| Unsatisfactory Cleanup [32] | Incorrect purification strategy; poorly chosen wash/elution solvents. | Use a strategy that retains the analyte and removes the matrix; re-optimize wash conditions (composition, pH, ionic strength). |

| Incorrect Measurement & Contamination [28] | Using wrong pipette tips; misreading volumes; cross-contamination. | Master accurate measurement skills; use correct pipetting technique; never re-use pipette tips across samples. |

| Poor Flow Rate in SPE [32] | Particulate clogging; high sample viscosity; variations in sorbent packing. | Filter or centrifuge samples before loading; dilute sample with matrix-compatible solvent; use a controlled manifold. |

FAQs on Sample Preparation

1. Why is sample preparation considered the most critical stage in analytical chemistry? Sample preparation is the most time-consuming stage and has the greatest impact on the final results. Its primary roles include concentrating the analyte, isolating it from a complex matrix, removing interferents, and sometimes changing the matrix or derivatizing the analyte to make it detectable. Proper preparation is fundamental for achieving accuracy, reproducibility, and sensitivity [33] [1].

2. What are the key differences between conventional and innovative solid-liquid extraction techniques? Conventional techniques like maceration and Soxhlet extraction are often characterized by long extraction times, high solvent consumption, low selectivity, and potential thermal degradation of compounds due to heating. Innovative techniques like Rapid Solid-Liquid Dynamic Extraction (RSLDE), ultrasound-assisted extraction (UAE), and microwave-assisted extraction (MAE) aim to reduce extraction times and solvent use, improve efficiency and selectivity, and prevent analyte degradation [30].

3. How can electrostatic charges in powder handling be effectively mitigated? Electrostatic troubleshooting requires a layered approach. Key strategies include:

- Grounding: Ensure all parts of the system are electrically bonded and grounded.

- Environmental Control: Maintain relative humidity above 40% to allow charge dissipation through moisture films.

- Equipment Design: Use conductive materials instead of insulative polymers, and design systems with smooth radii to reduce charge generation.

- Powder Modification: Use flow aids like fumed silica or approved anti-static agents [29].

4. What steps can be taken to improve reproducibility in Solid-Phase Extraction? To ensure high reproducibility in SPE:

- Prevent the sorbent bed from drying out before sample loading by ensuring proper conditioning and equilibration.

- Control and reduce the flow rate during sample application to allow sufficient contact time.

- Avoid overloading the cartridge by using an appropriately sized sorbent mass for the amount of analyte.

- Use a controlled vacuum or pressure manifold for consistent flow rates [32].

5. What are Metal-Organic Frameworks (MOFs) and why are they used in extraction? MOFs are crystalline porous materials consisting of metal ions or clusters connected by organic linkers. They are increasingly used as sorbents in techniques like Solid-Phase Extraction (SPE) due to their exceptional properties, which include a very high specific surface area (up to ~7000 m²/g), a tunable pore size, and a wide possibility for chemical modification. This allows for high sorption capacity and selectivity for target analytes [33].

Experimental Protocols and Workflows

Protocol: Countercurrent Solid-Liquid Extraction

This protocol is used for efficient extraction of solutes (e.g., lycopene from fungus) using a limited quantity of solvent to obtain a concentrated extract [31].

- Define Stream Compositions:

- Feed Slurry (E₀): Characterize the inert-to-solution ratio (N = B/(A+C)) and solute concentration in the imbibed solution (y = C/(A+C)) of the input solid.

- Fresh Solvent (Rₚ₊₁): Define the composition of the incoming liquid, typically with a solute concentration x=0 for pure solvent.

- Determine Process Specifications:

- Establish the feed-to-solvent mass ratio and the desired yield of recovery for the extractable solute.

- Calculate the composition of the final spent solids (E_p) and the final extract (R₁) using material balance.

- Set Up the Extraction System:

- Configure a multi-stage system where the solid and liquid streams move in opposite directions (countercurrent). The raw material is fed to the first stage, and fresh solvent is fed to the last stage.

- Execute Multistage Extraction:

- In each stage, the solid and liquid streams are mixed and then separated.

- The extract from stage n (Rn) is assumed to be in equilibrium with the solution imbibed in the slurry leaving the same stage (En), meaning yₙ = xₙ.

- Calculate Number of Stages:

- Use graphical methods (e.g., the Ponchon-Savarit diagram) or mathematical modeling with the material balance equation (Eₙ₋₁ - Rₙ = Eₙ - Rₙ₊₁ = Constant = Δ) to determine the number of theoretical contact stages required to achieve the target recovery [31].

Countercurrent Solid-Liquid Extraction Process

Protocol: Troubleshooting Electrostatic Powder Handling

This protocol provides a systematic approach to identifying and resolving electrostatic issues in powder processes [29].

- Symptom Recognition:

- Observe the process for classic signs of electrostatic issues: powder clinging to hopper walls, segregation after mixing, irregular dosing, audible crackling, or operator shocks.

- Quantitative Measurement:

- Faraday Pail: Use a conductive pail connected to an electrometer to measure the total charge of a powder sample. Calculate the charge-to-mass ratio (in nC/g) to compare different powders or process conditions.

- Charge Decay: Charge the powder in a controlled manner and monitor how quickly it loses charge. This determines the material's ability to dissipate charge over time.

- Tribocharge Testing: Pass the powder through tubes made of different materials (e.g., steel, PTFE) to see how equipment interactions influence charge generation.

- Environmental Assessment:

- Measure the relative humidity and temperature of the process environment. Repeat tests at different humidity levels (e.g., 20% RH vs. 45% RH) to identify thresholds where electrostatic behavior becomes problematic.

- Implement Mitigation Strategies:

- Grounding: Inspect and ensure all system components are electrically grounded.

- Humidity Control: If possible, install humidification systems to maintain RH above 40%.

- Equipment Modification: Replace insulative components (e.g., polymer hoses) with conductive alternatives.

- Powder Treatment: Introduce flow aids or approved anti-static agents to the powder.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Materials

Table: Key Materials for Sample Preparation in Solid-Liquid Extraction

| Item | Function | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Metal-Organic Frameworks (MOFs) [33] | High-performance sorbents for solid-phase extraction due to ultra-high surface area and tunable porosity. | Select based on target analyte; consider stability in water; available in various forms for different SPE techniques. |

| Solid-Phase Extraction (SPE) Cartridges [32] | Devices containing sorbents to isolate and concentrate analytes from a liquid sample. | Choose sorbent chemistry (reversed-phase, ion-exchange, etc.) to match analyte; do not let bed dry out before use. |

| Pipettes [28] [1] | For accurate measurement and transfer of liquid volumes. | Calibrate regularly; use proper technique to avoid air bubbles; never re-use tips to prevent cross-contamination. |

| Analytical Balances [28] [1] | For high-precision weighing of samples and reagents. | Calibrate regularly; account for environmental factors like air currents. |

| Naviglio Extractor [30] | Instrument for Rapid Solid-Liquid Dynamic Extraction (RSLDE) using a pressure gradient for active extraction. | Allows for fast, efficient extraction without heating, suitable for thermolabile compounds. |

| Powder Pump [34] | A pneumatic transfer system for moving powders in a closed, contained manner. | Reduces dust, improves safety, and automates manual powder charging processes. |

A Practical Guide to Traditional and Next-Generation Preparation Techniques

Troubleshooting Guides

Sectioning Troubleshooting

Problem: Sample shows excessive heat damage (discoloration, burned edges) after sectioning.

- Root Cause: High temperatures generated during the cutting process can alter the microstructure, induce thermal stress, cause phase changes, or even melt low-melting-point components [35].

- Solution:

- Prevention Protocol:

- Coolant Selection: Use water-based coolants for most situations; opt for oil-based variants to prevent oxidation of reactive metals [35].

- Parameter Adjustment: Select a lower cutting speed and a gentle, consistent feed pressure.

Problem: Sample exhibits mechanical deformation, cracks, or chatter marks.

- Root Cause: Improper clamping can cause vibration or distortion. Excessive feed pressure can also induce stress [35].

- Solution:

- Prevention Protocol: For thin or delicate specimens, consider embedding them in a temporary support medium or using vacuum fixtures that distribute holding force evenly [35].

Grinding and Polishing Troubleshooting

Problem: Scratches are present on the final polished surface.

- Root Cause: Scratches are grooves produced by abrasive particles. They remain if damage from a previous preparation step is not completely removed [36].

- Solution:

- Ensure that after planar grinding, all samples show a uniform scratch pattern [36].

- Clean the samples and specimen holder meticulously after every step to avoid contamination from large abrasive particles from a previous step [36].

- If scratches from the previous step remain, first increase the preparation time of the current step by 25% to 50% [36].

- Prevention Protocol: Follow a strict sequential abrasive grit sequence, ensuring each step removes the scratches from the previous one. Rotate the specimen 90° between steps [36] [37].

Problem: The specimen has rounded edges or "relief" between different material phases.

- Root Cause: Excessively long preparation times or using a mounting medium that is too soft for the sample can lead to edge rounding and relief [36] [35].

- Solution:

- Prevention Protocol: For excellent edge retention, especially with hard materials, use hot mounting with phenolic or epoxy resins [35].

Problem: The surface appears smeared, hazy, or stained.

- Root Cause: This is often caused by contamination, such as abrasive grains from a previous step being carried over, or the use of insufficient or incorrect lubricants [36] [38]. It can also result from polishing a soft material without adequate lubrication, leading to "comet tails" around harder inclusions [36].

- Solution:

- Prevention Protocol: Use alcohol-based or specially formulated lubricants to prevent corrosion and effectively remove debris. For soft materials like aluminum or magnesium, adequate lubrication is critical to prevent smearing [35] [37].

Problem: Images under the microscope are blurry or out of focus, with a loss of detail.

- Root Cause (Sample Preparation): This can be due to residual deformation, scratches, or a poorly prepared surface. It may also be caused by contaminating oil on the objective lens or an incorrectly positioned microscope slide (e.g., placed upside down) [38].

- Solution:

- Re-examine and re-prepare the sample, ensuring the final polishing step removes all microscopic scratches. Vibratory polishing can be effective for producing deformation-free surfaces [35].

- Check that the microscope slide is oriented with the coverslip facing the objective [38].

- Inspect and clean the microscope's objective lens if necessary [38].

- Prevention Protocol: For critical examinations, use a final polishing step with a fine colloidal silica suspension (0.05–0.02 µm) to achieve a scratch-free, high-quality finish [35].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What is the single most important rule for successful grinding and polishing? The most critical rule is to remove all damage from the previous step before moving to the next, finer abrasive. If scratches from grinding are not fully eliminated, they will persist through polishing and be visible under the microscope [36].

Q2: How do I select the correct starting grit for grinding? Always begin with the smallest possible grain size (coarsest grit) that will efficiently remove the sectioning damage and level the specimen. Starting too coarse will unnecessarily deepen the deformation; starting too fine will make the process inefficient [36]. For heavy stock removal, begin with 80-120 grit SiC paper [37].

Q3: What is the purpose of rotating the sample between grinding/polishing steps? Rotating the specimen by 90° between steps ensures that scratches from the previous, coarser abrasive are easily visible and can be completely removed by the current step. This helps achieve a uniform surface and prevents deep, persistent scratches [37].

Q4: Why is lubrication so important during grinding and polishing? Lubrication serves three key purposes: it cools the sample to prevent thermal damage, it flushes away debris to prevent contamination and scratching, and it reduces friction to minimize mechanical deformation and smearing, especially in soft materials [36] [35] [37].

Q5: My polished sample looks hazy under the microscope. What could be the cause? A hazy appearance is often due to residual fine scratches or smearing of soft phases. This can be caused by insufficient cleaning between steps, contaminated polishing cloths, or inadequate lubrication during the final polish. A final polish with colloidal silica or vibratory polishing can often resolve this [35].

Standard Grinding and Polishing Sequence

Table 1: Typical abrasive sequence for mechanical preparation.

| Step | Abrasive Type | Grit / Particle Size | Purpose / Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|

| Planar Grinding | Silicon Carbide (SiC) Paper | 120 - 240 grit | Remove sectioning damage, achieve flatness [37]. |

| Fine Grinding | Silicon Carbide (SiC) Paper | 320 - 600 grit | Remove coarse scratches, refine surface [37]. |

| Coarse Polishing | Diamond Suspension | 9 µm | Remove grinding scratches, begin polishing [35]. |

| Intermediate Polishing | Diamond Suspension | 3 µm | Refine surface, remove scratches from 9 µm step [35]. |

| Final Polishing | Colloidal Silica | 0.05 - 0.02 µm | Produce scratch-free, mirror-like finish for analysis [35]. |

Key Preparation Parameters

Table 2: Standardized parameters for mechanical preparation.

| Parameter | Typical Setting / Rule | Notes and Adjustments |

|---|---|---|

| Force | Standardized for a holder with 6x Ø30mm specimens [36]. | Reduce force for smaller/fewer specimens to avoid damage. Slightly increase force or extend time for larger specimens [36]. |

| Rotational Speed | 150 rpm for fine grinding and polishing [36]. | High disk speed for planar grinding for fast material removal [36]. |

| Lubricant | Balanced for cooling and lubrication [36]. | Soft materials require more lubricant; hard materials require less lubricant but more abrasive [36]. The cloth should be moist, not wet [36]. |

| Time | Keep as short as possible [36]. | Extend time for larger specimens. Increase time by 25-50% if scratches from previous step persist [36]. |

Experimental Workflow and Diagnostics

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential materials and consumables for mechanical preparation.

| Material / Consumable | Primary Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Abrasive Cut-off Wheels | To section a representative sample from the bulk material with minimal damage [35]. | Selection depends on material hardness. Use coolant to minimize heat-affected zones [35]. |

| Mounting Resins (Epoxy/Phenolic) | To encapsulate the specimen for easy handling and to preserve edge integrity during preparation [35]. | Hot mounting resins (phenolic) offer superior edge retention for hard materials. Cold mounting (epoxy) is for heat-sensitive or porous samples [35]. |

| Silicon Carbide (SiC) Paper | For the grinding steps to remove damage and create a flat surface with progressively finer scratches [36] [37]. | Used in a sequence of coarse to fine grits (e.g., P120 -> P240 -> P320 -> P600). |

| Diamond Suspensions | For the polishing steps to remove the fine scratches from grinding and achieve a smooth, reflective surface [35]. | Polycrystalline diamonds are preferred for high material removal with shallow scratch depth. Used with a lubricant on a synthetic polishing cloth [36]. |

| Colloidal Silica | For final polishing to produce a deformation-free, scratch-free, high-quality surface finish for microscopic analysis [35]. | Used after diamond polishing on a chemoresistant cloth for the ultimate surface quality. |

| Polishing/Lapping Lubricants | To cool the sample, reduce friction, and remove debris during grinding and polishing [36]. | Prevents damage, smearing, and embedding of abrasive particles. Can be water-based or alcohol-based [35] [37]. |

Ion milling is a cornerstone sample preparation technique for high-resolution microscopy. It uses a directed stream of ions to precisely remove material from a sample's surface, creating ultra-smooth, defect-free surfaces essential for techniques like Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM) and Transmission Electron Microscopy (TEM). Unlike mechanical polishing, it is a non-contact process that avoids introducing scratches, deformation, or embedded debris [39] [40].

This technical guide focuses on two primary configurations of ion milling:

- Broad-Area Flat Milling: A technique designed to polish large, flat surfaces, typically on the millimeter to multi-millimeter scale, by rotating the sample under a broad ion beam [41].

- Cross-Section Polishing: A technique where a sample is mounted edge-on behind a mask and milled by the ion beam to reveal internal structures and create a clean cross-sectional face [42] [41].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

1. What is the fundamental difference between broad-area flat milling and cross-section polishing? The core difference lies in the objective and the resulting sample geometry. Broad-area flat milling is designed to create a large, polished surface on the face of a sample, ideal for techniques like EBSD that require a wide, damage-free area. Cross-section polishing is used to cut into a sample to reveal a view of its internal layers and interfaces, which is crucial for analyzing coatings, thin films, and buried features [41].

2. When should I choose flat milling over cross-section polishing? Choose flat milling when your analysis requires a large, high-quality surface on the face of your sample mount. This is particularly suited for petrologic context in geologic materials [41], for preparing surfaces for Electron Backscatter Diffraction (EBSD) [42] [40], or for creating uniform surfaces on multi-material samples. Choose cross-section polishing when you need to investigate internal structures, layer thicknesses, subsurface defects, or interfaces within a material [42] [43].

3. How does ion milling compare to Focused Ion Beam (FIB) for sample preparation? Ion milling and FIB are complementary techniques. Broad-ion beam (BIB) milling, which includes both flat and cross-section methods, excels at preparing large areas (millimeter-scale) quickly and with minimal damage. FIB uses a finely focused gallium ion beam for nanometer-scale precision, making it ideal for site-specific tasks like preparing TEM lamellae from exact locations. However, FIB is inefficient and time-consuming for large-area preparation [39] [44].

4. What are the best practices for mounting samples to minimize artifacts? Proper mounting is critical for a clean result.

- For Flat Milling: The sample surface should be flat and securely fixed to the stage [41].

- For Cross-Section Polishing: Ensure a flat mounting surface to prevent tilt. Minimize the overhang of the sample under the mask (typically ≤100 µm) for better control. Use strong, conductive adhesives to prevent sample shifting and eliminate air gaps between the sample and mask to prevent uneven milling [43].

5. My sample is heat-sensitive. How can I prevent thermal damage during milling? Ion milling can induce significant sample heating. Several techniques can manage this:

- Cryo-Cooling: Use a system with a liquid nitrogen-cooled stage to actively remove heat [43] [41].

- Lower Acceleration Voltage: Reducing the beam energy decreases heat input [43].

- Intermittent (Pulsed) Milling: Cycling the ion beam on and off allows the sample to cool between exposures [43] [44].

- Improve Heat Conduction: Adding metal foil around the sample can help distribute heat more evenly [43].

6. What are "curtaining effects" and how can I reduce them? Curtaining is a streaking artifact that occurs when materials with different hardness or sputtering rates erode at different speeds [43] [45]. To minimize it:

- Use Swing Mode: Gently oscillating the sample during milling averages out the angle of incidence [43].

- Optimize Acceleration Voltage: Balance the material removal rates between hard and soft phases [43].

- Ensure Proper Mask Overhang: This promotes even milling across the sample face [43].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem 1: Poor Surface Finish or Roughness

| Possible Cause | Solution |

|---|---|

| Incorrect acceleration voltage (too high) | Use a stepped protocol: start with a higher voltage (6-8 kV) for faster removal, and finish with a low voltage (0.5-2 kV) for a final polish [43]. |

| Insufficient milling time | Increase the total milling duration, especially for the final low-voltage polishing step. |

| Sample not rotating (flat milling) | Ensure the sample rotation is active during flat milling to ensure uniform material removal [41]. |

| Initial surface was too rough | The quality of the pre-milled surface is critical. A well-prepared initial surface (e.g., mechanically polished) will yield better results in less time [46]. |

Problem 2: Inconsistent Milling or Artifacts

| Possible Cause | Solution |

|---|---|

| Curtaining effects | Implement sample swing or rotation during milling. Optimize the acceleration voltage and ensure minimal and uniform sample overhang under the mask [43]. |

| Poor sample mounting | Check for secure adhesion and the absence of air gaps, especially between the sample and mask in cross-section polishing [43]. |

| Sample charging (non-conductive samples) | Ensure the sample mount is conductive. Use a carbon tape or a conductive adhesive. Some systems offer charge neutralization features. |

| Contamination of the ion source | Follow manufacturer-recommended maintenance schedules for the ion source and vacuum system. |

Problem 3: Overheating or Damage to Sensitive Samples

| Possible Cause | Solution |

|---|---|

| Excessive beam current/energy | Lower the acceleration voltage and beam current to reduce the energy input [43]. |

| No active cooling | For heat-sensitive materials (e.g., polymers, biologics), use the cryogenic cooling stage if available [43] [41]. |

| Continuous milling | Switch to intermittent (pulsed) milling mode to allow for heat dissipation between beam exposures [43] [44]. |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Standard Broad-Area Flat Milling for EBSD

Objective: To produce a large, strain-free surface on a metallographic sample for high-quality Electron Backscatter Diffraction (EBSD) analysis.

Workflow: The following diagram illustrates the flat milling setup and process.

- Initial Preparation: Begin with a sample that has been mechanically sectioned, mounted, and polished to a reflective finish using traditional metallographic techniques [46].

- System Setup: Mount the sample onto the flat milling stage. Introduce argon gas into the vacuum chamber and initiate the ion source.

- Parameter Selection:

- Execution: Initiate the milling process with continuous sample rotation. The total time can range from several hours to achieve a polish over a large area [41].

Protocol 2: Cross-Section Polishing of a Multi-Layer Sample

Objective: To create a clean, artifact-free cross-section through a multi-layer sample (e.g., a semiconductor device or a coated material) to reveal internal interfaces.

Workflow: The following diagram illustrates the cross-section polishing setup.

- Sample Mounting: This is the most critical step. The sample is adhered to a carrier plate. A titanium or tungsten carbide mask is placed so that only the edge of the sample, where the cross-section is desired, is exposed to the ion beam. The area of interest must be precisely aligned to the mask edge [43] [46].

- System Setup: Load the mounted sample into the cross-section polisher. The sample is typically stationary or oscillates slightly (swing mode).

- Parameter Selection:

- Execution: Initiate milling. The ion beam will erode the exposed edge of the sample, creating a clean cross-section. Process time depends on the material and the desired depth.

The Researcher's Toolkit

| Item | Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| Broad Ion Beam (BIB) System | Generates a wide, low-energy ion beam for large-area, damage-free milling [39]. | Essential for broad-area flat milling and large cross-sections. |

| Conductive Adhesives | Securely mounts samples to the stage, preventing shift and dissipating charge. | Critical for all sample mounting, especially for non-conductive samples. |

| Sputter-Resistant Mask | A hard mask (Ti or WC) that shields parts of the sample to define the milling area [43]. | Required for cross-section polishing to create a sharp edge. |

| Cryogenic Cooling Stage | Actively cools the sample holder using liquid nitrogen to prevent thermal damage [43] [41]. | Mandatory for heat-sensitive materials (polymers, biologics, some battery materials). |

| Pulsed Milling Software | Allows the ion beam to be cycled on and off to reduce average power and heat buildup [43]. | Used for soft, sensitive, or thermally labile samples. |

Advanced Ion Polishing with Cryogenic Cooling for Sensitive Samples

Troubleshooting Guides

Troubleshooting Common Cryogenic Ion Milling Issues

Table 1: Common Issues and Solutions in Cryogenic Ion Polishing

| Problem | Possible Causes | Recommended Solutions | Preventive Measures |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sample overheating/melting | Ion beam parameters too aggressive; Poor thermal conductivity of sample; Inadequate cooling [43] | Lower acceleration voltage (e.g., to 500V-2kV); Use pulsed (intermittent) ion beam milling; Apply metal foil around sample to improve heat dissipation [43]; Ensure cryo-stage is at correct temperature (e.g., -100°C to -135°C) [47] [48] | Optimize milling parameters empirically for each material; Use conductive adhesives for mounting; Allow sufficient time for sample to equilibrate to cryogenic temperature [43] |

| Curtaining (uneven milling) | Different erosion rates in multi-material samples; Incorrect sample overhang; Lack of sample movement [43] | Use sample "swing mode" during milling (e.g., ±15° to ±40°) [47]; Optimize acceleration voltage to balance removal rates; Ensure sample overhang under mask is minimal (≤100 µm) [43] | Ensure flat mounting surface; Use a mask material with high sputter resistance (e.g., Tungsten Carbide) [43] |

| Hydride formation (in Ti/alloys) | Hydrogen pick-up during room-temperature preparation [48] | Use cryogenic FIB milling at temperatures below -135°C to suppress hydrogen diffusion [48] | Avoid electrochemical polishing and room-temperature FIB for hydrogen-sensitive materials [48] |

| Ice contamination | Water vapor condensation on cryogenic sample during transfer or in vacuum chamber [49] | Use a glove box purged with dry nitrogen for sample handling; Utilize a high-vacuum cryo-transfer system; Employ a cryo-shield and cryo-shutter in the milling chamber [49] | Pre-cool all handling tools and stations; Heat the glove box to 40-50°C during milling to prevent frost [49] |

| Low milling rate | Acceleration voltage too low; Ion beam current too low [50] [47] | For rough milling, increase voltage (e.g., 6-8 kV) and current [43]; Ensure ion source is correctly aligned | Balance speed with surface quality requirements; Use high rates for initial milling, lower voltages for final polish [43] |

Optimizing Parameters for Specific Materials

Table 2: Milling Parameter Guidance for Different Sample Types

| Material Type | Acceleration Voltage | Cryogenic Cooling | Key Considerations | Target Application |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Polymers & Soft Materials | Low (0.5 - 2 kV) [43] | Mandatory (e.g., -100°C) [47] | Use beam pulsing to prevent melting [43] | Preserving native structure of soft interfaces [40] [51] |

| Ti and Ti Alloys | Standard (e.g., 2-8 kV) | Mandatory (< -135°C) [48] | Prevents hydrogen pick-up and artefactual hydride formation [48] | Hydrogen embrittlement studies, microstructural analysis [48] |

| Battery Materials (Electrodes/Separators) | Low to Moderate [40] | Highly Recommended | Prevents thermal damage to sensitive components [40] [51] | Failure analysis, interface studies [40] |

| Metals & Alloys (for EBSD) | Final Polish: Low (500V - 2 kV) [43] | Optional | Low voltage produces smooth, strain-free surfaces for high-quality Kikuchi patterns [43] | Electron Backscatter Diffraction (EBSD) [40] [43] |

| Composite Materials | Adjust based on component hardness [43] | Recommended for delicate components | Swing mode and parameter adjustment minimize curtaining between hard/soft phases [43] | Analysis of carbon fibers, multilayer devices [40] [43] |

| Semiconductors/Electronics | Standard | Optional for most | Ensure flat mounting and minimal overhang for clean cross-sections [43] | Solder joint inspection, failure analysis [40] [47] |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

System Configuration and Capabilities

Q1: What is the fundamental difference between broad ion beam milling and focused ion beam (FIB) milling?

A: The key difference lies in the beam size and primary application. Broad Ion Beam (BIB) systems use a wide-area ion beam to uniformly polish or create large cross-sections (up to 8-10 mm wide) for SEM, EDS, and EBSD analysis, making them ideal for preparing large areas for analysis [40] [43] [47]. Focused Ion Beam (FIB) systems use a tightly focused beam (typically Gallium or Xenon plasma) to selectively mill very small, precise regions (10-20 microns), which is common in site-specific failure analysis and TEM lamella preparation [40] [43] [52]. For large-area sample preparation, BIB is significantly faster [43].

Q2: What are the typical temperature ranges for cryogenic cooling stages, and how is temperature controlled?

A: Cryogenic stages typically use liquid nitrogen (LN2) for cooling. Specific systems, like the Hitachi ArBlade 5000, allow for set-point temperature control from 0°C down to -100°C [47]. For more extreme cooling, some FIB systems can reach temperatures as low as -135°C [48]. Temperature is often controlled via a digital Cryo Temperature Control (CTC) unit, which places a heater and sensor directly at the milling stage to accurately maintain the desired process temperature [47].

Q3: Can ion milling be combined with other processing techniques?

A: Yes, hybrid workflows are increasingly common. Laser milling is much faster for rough shaping but produces a rougher surface; it can be effectively followed by BIB for fine polishing and surface refinement [43]. Furthermore, systems like the ArBlade 5000 offer a hybrid model with dedicated configurations for both cross-section milling and flat milling within the same instrument [47] [51].

Process and Methodology

Q4: Why is a mask needed during cross-section milling, and what materials are suitable?

A: The mask ensures a sharp edge by preventing the ion beam from hitting the sample perpendicularly, which would otherwise create a deep hole instead of a smooth cross-section [43]. The mask material must be highly resistant to sputtering. The best practices recommend using Titanium or Tungsten Carbide for this purpose due to their high sputter resistance [43]. Some systems also offer an optional "higher beam tolerance mask" that is twice as hard as the standard mask [47].

Q5: How does cryo-cooling actually protect heat-sensitive samples?

A: Cryo-cooling works by indirectly cooling the sample holder and mask using liquid nitrogen, effectively removing the heat induced during ion-beam milling [47]. However, its efficacy also depends on the sample's thermal conductivity. For samples with poor conductivity (like many polymers), heat may not dissipate quickly from the point of ion impact. Therefore, even with active cooling, it is critical to choose proper processing parameters (low voltage, pulsed beam) for the best results [43] [47].

Q6: What are the best practices for mounting samples to minimize artifacts?

A: Proper mounting is critical for a clean cross-section [43].

- Flat Surface: Ensure a flat mounting surface to prevent tilt.

- Minimal Overhang: Keep the sample overhang under the mask small (≤100 µm) for better control.

- Strong Adhesive: Use strong, conductive adhesives to avoid sample shifting during milling.

- Eliminate Gaps: Remove any air gaps between the sample and the mask to prevent uneven milling [43].

Experimental Protocols and Workflows

Standard Workflow for Cryogenic Ion Polishing

The following diagram visualizes the standard workflow for preparing a sensitive sample using cryogenic ion polishing, integrating key steps from system preparation to final analysis.

Cryo Ion Polish Workflow

Detailed Protocol: Cryo-FIB Milling for Lamella Preparation (Biological Samples)

This protocol is adapted for preparing thin lamellae from frozen cells for cryo-Electron Tomography (cryo-ET) [52].

- Cell Plating and Freezing: Grow or deposit cells directly on EM grids. Plunge-freeze the grids in a commercial or homemade plunger to achieve vitrification [52].

- Grid Mounting: Mount the plunge-frozen EM grids into a solid metal ring (e.g., Cryo-FIB AutoGrid) to ensure mechanical stability during subsequent transfers [52].

- Cryo-Fluorescence Microscopy (Optional): If regions or proteins of interest are fluorescently labeled, perform cryo-fluorescence microscopy to identify target cells for milling [52].

- Loading into Cryo-DualBeam Microscope: Load the grids into a cryo-SEM/FIB dual beam microscope (e.g., Aquilos Cryo-FIB) using a high-vacuum cryo-transfer system to prevent ice contamination [52] [49].

- Protective Coating: Coat the grid with a protective organometallic platinum layer using a Gas Injection System (GIS) to prevent damage during milling [49].

- Rough Milling: Use a high ion current (e.g., 700 pA) at 30 kV to carve out bulk material and create a thick lamella [49].

- Fine Polishing ("Polishing"): Use progressively lower ion currents (e.g., down to 50 pA) to thin the lamella to the desired final thickness (typically 100-250 nm) [52] [49].

- Transfer for TEM: Transfer the lamella back to the glove box and mount it into an autoloader cassette for subsequent cryo-ET analysis [52] [49].

Critical Considerations:

- Contamination Control: The use of a glove box purged with dry nitrogen, a high-vacuum transfer system, and a cryo-shield inside the milling chamber is essential to reduce frost and amorphous ice contamination [49].

- Automation: Software packages (e.g., AutoTEM Cryo) can automate the milling process, allowing for batch milling of multiple lamellae [49].

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Cryogenic Ion Milling

| Item | Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Liquid Nitrogen (LN2) | Primary cryogen for cooling stages; provides temperatures down to -196°C [47] [53]. | Used in cryo-stages for heat removal and in cold traps to condense water vapor in vacuum systems [47] [53]. |

| High-Purity Argon Gas | The most common source gas for generating argon ions in the broad ion beam [50] [47]. | High-purity gas with precise flow control is required for stable beam operation and to prevent contamination [50]. |

| Conductive Adhesives | To mount samples securely, ensuring electrical and thermal contact with the holder [43]. | Critical for heat dissipation and preventing sample charging or shifting during milling [43]. |

| Sputter-Resistant Masks | To create a sharp edge for cross-sectioning by shielding parts of the sample from the ion beam [43]. | Materials like Titanium or Tungsten Carbide are preferred due to their high resistance to sputtering [43] [47]. |

| Cryo-Temperature Control Unit | A digital controller to set and maintain a precise temperature at the milling stage [47]. | Allows operators to set a desired temperature (e.g., 0°C to -100°C) which is accurately maintained during milling [47]. |

| Organometallic Platinum Gas | Used in a Gas Injection System (GIS) to deposit a protective layer on sensitive samples prior to milling [49]. | Primarily used in cryo-FIB of biological samples to protect the surface from ion beam damage [49]. |

Frequently Asked Questions