Ultra-High Vacuum Surface Preparation: Protocols, Optimization, and Validation for Advanced Research

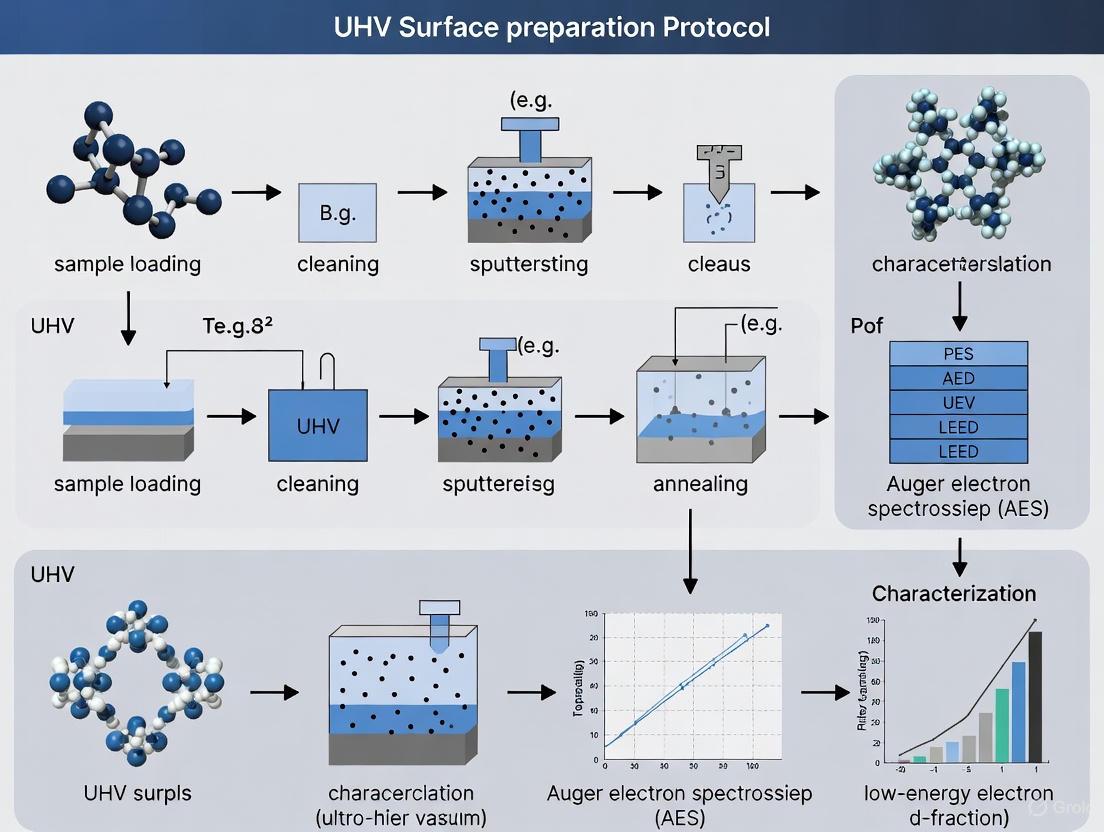

This article provides a comprehensive guide to Ultra-High Vacuum (UHV) surface preparation, a critical process for research in surface science, pharmaceuticals, and advanced materials.

Ultra-High Vacuum Surface Preparation: Protocols, Optimization, and Validation for Advanced Research

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide to Ultra-High Vacuum (UHV) surface preparation, a critical process for research in surface science, pharmaceuticals, and advanced materials. It covers the foundational principles of UHV environments, detailed protocols for various materials, strategies for troubleshooting and optimization, and advanced techniques for surface validation. Aimed at researchers and scientists, the content synthesizes current methodologies to ensure the achievement of atomically clean, well-defined surfaces essential for reliable experimental results in fields ranging from high-energy physics to drug development.

UHV Fundamentals: Principles and Material Considerations for Pristine Surfaces

Ultra-High Vacuum (UHV) describes a vacuum environment characterized by pressures lower than approximately 1×10⁻⁷ Pascals (Pa), 1×10⁻⁹ torrs, or 1×10⁻⁷ millibars (mbar) [1] [2]. This regime represents the ultimate evolution of high vacuum, creating conditions essential for advanced scientific research and industrial processes where molecular-level cleanliness is paramount. The fundamental importance of UHV lies in its ability to drastically reduce the number of gas molecules in a chamber, thereby enabling the creation and maintenance of atomically clean surfaces for extended periods [3].

In UHV systems, the mean free path of gas molecules—the average distance a molecule travels between collisions—exceeds several tens of kilometers [1]. This means that gas molecules are far more likely to collide with chamber walls than with each other, causing almost all molecular interactions to occur at surfaces within the chamber. Consequently, UHV conditions are indispensable for surface science experiments, where even minute levels of contamination can compromise results and invalidate experimental findings.

Quantitative Definition of the UHV Regime

Pressure Ranges in Vacuum Technology

Vacuum technology classifies pressure ranges based on physical behavior and technical requirements. The transition from high vacuum (HV) to UHV marks a critical threshold where different physical laws govern gas behavior and specialized techniques are required for pressure maintenance. The table below summarizes the standard vacuum classifications with a focus on the UHV regime and its bordering ranges.

Table 1: Vacuum Classification Regimes

| Regime | Pressure Range (mbar) | Pressure Range (Pa) | Dominant Gas Species | Primary Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| High Vacuum (HV) | 10⁻³ to 10⁻⁷ | 10⁻¹ to 10⁻⁵ | Water vapor (H₂O) [2] | Thin film deposition, electron microscopy |

| Ultra-High Vacuum (UHV) | 10⁻⁷ to 10⁻¹² | 10⁻⁵ to 10⁻¹⁰ | Hydrogen (H₂), Carbon Monoxide (CO) [1] [2] | Surface science, particle accelerators |

| Extreme High Vacuum (XHV) | <10⁻¹² | <10⁻¹⁰ | Hydrogen, helium [4] [5] | Space simulation, fundamental research |

Gas Dynamics in UHV Environments

The exceptional properties of UHV environments can be quantified through key gas dynamics parameters derived from kinetic theory. These parameters highlight the profound difference between UHV and conventional vacuum environments.

Table 2: Gas Dynamics Parameters at Room Temperature (300K) for Nitrogen

| Pressure (mbar) | Gas Density (molecules/cm³) | Mean Free Path | Time to Form a Monolayer | Incident Flux (molecules cm⁻² s⁻¹) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 10⁻⁶ (High Vacuum) | ~3 × 10¹⁰ [6] | ~50 m [3] | Minutes to hours | ~10¹⁴ [6] |

| 10⁻⁹ (UHV) | ~3 × 10⁷ [6] | ~50 km [1] [3] | Several hours to days [3] | ~10¹¹ [6] |

| 10⁻¹² (XHV) | ~3 × 10⁴ [6] | ~50,000 km | Weeks to months | ~10⁸ [6] |

The incident flux (F) of gas molecules striking a surface is calculated using the Hertz-Knudsen equation [6]: [ F = \frac{P}{\sqrt{2 \pi m k T}} ] where P is pressure, m is molecular mass, k is Boltzmann's constant, and T is temperature. This relationship demonstrates why UHV is essential for maintaining clean surfaces—the rate of surface contamination is directly proportional to the incident gas flux, which decreases linearly with pressure.

The Critical Need for UHV in Surface Science

Maintaining Surface Cleanliness

The most fundamental requirement for UHV in surface science is the preservation of atomically clean surfaces for experimentally relevant timeframes. At a pressure of 10⁻⁶ mbar (high vacuum), a monolayer of contaminant gas forms on a surface in seconds to minutes, assuming a sticking coefficient near unity [6]. In contrast, at UHV pressures of 10⁻⁹ mbar, this contamination process slows dramatically, taking several hours to days to form a single monolayer [3]. This extended timescale enables researchers to prepare pristine surfaces and conduct meaningful experiments before significant contamination occurs.

The dominant residual gases in a properly prepared UHV system are hydrogen and carbon monoxide, which diffuse out from the grain boundaries in stainless steel chamber walls [1]. These gases present less interference with many surface analysis techniques compared to the water vapor that predominates in high vacuum systems, further enhancing the utility of UHV for sensitive measurements.

Enabling Electron and Ion-Based Analytical Techniques

Many essential surface analysis techniques rely on the manipulation of charged particles—electrons or ions—which would experience severe scattering and deflection if they encountered gas molecules along their paths. The extensive mean free path in UHV conditions, reaching tens of kilometers [1], ensures that these particles can travel from source to sample to detector without significant interference.

Specific techniques that require UHV conditions include:

- X-ray Photoelectron Spectroscopy (XPS): Measures elemental composition and chemical state [1]

- Auger Electron Spectroscopy (AES): Provides elemental surface analysis [3]

- Low Energy Electron Diffraction (LEED): Determines surface crystal structure [7]

- Secondary Ion Mass Spectrometry (SIMS): Offers elemental and isotopic surface analysis [4] [3]

- Low Energy Ion Scattering (LEIS): Provides composition of the outermost atomic layer [1]

Without UHV conditions, the electron and ion beams used in these techniques would be scattered by gas molecules, resulting in signal degradation, poor resolution, and potentially complete inability to perform measurements.

Essential UHV System Components and Protocols

UHV System Design and Pumping Strategy

Achieving UHV requires a systematic approach to chamber design and pumping technology. No single vacuum pump can operate effectively from atmospheric pressure to UHV, necessitating a multi-stage pumping strategy [1]. A typical sequence begins with a roughing pump (such as a scroll or diaphragm pump) to reduce pressure from atmosphere to approximately 10⁻³ mbar, followed by high-performance pumps capable of reaching lower pressures.

Table 3: UHV Pumping Technologies

| Pump Type | Operating Principle | Ultimate Pressure (mbar) | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Turbomolecular Pump | High-speed turbine blades impart momentum to gas molecules [1] [2] | 10⁻⁸ to 10⁻¹¹ [2] | High pumping speed for most gases, reliable | Mechanical parts require maintenance, vibration |

| Ion Pump | Ionizes gas molecules and implants them in cathode material [1] [2] | <10⁻¹¹ [2] | No moving parts, quiet operation, clean | Lower pumping speed, struggles with noble gases |

| Titanium Sublimation Pump | Evaporated titanium films getter active gases [1] | Can enhance other pumps | High pumping speed for active gases | Limited capacity, requires regeneration |

| Cryopump | Traps gas molecules on cryogenically cooled surfaces [1] [2] | <10⁻¹⁰ [2] | Very high pumping speeds for all gases | Requires regeneration, limited by gas capacity |

UHV System Protocol: Chamber Preparation and Bake-Out

A critical protocol for achieving UHV is the proper preparation and bake-out of the vacuum chamber. The following workflow outlines the essential steps:

The bake-out process involves heating the entire UHV system to temperatures between 200°C and 400°C for 24-48 hours while the vacuum pumps are running [1]. This thermal treatment dramatically accelerates the desorption of water vapor and hydrocarbons that have adsorbed on the chamber walls. Without baking, these contaminants would desorb slowly at room temperature, potentially preventing the system from ever reaching UHV conditions or requiring months to do so [3]. After baking, the dominant residual gases in a UHV system shift from water vapor to hydrogen and carbon monoxide, which originate from the diffusion of hydrogen from the stainless steel chamber walls [1].

Material Selection for UHV Compatibility

Material compatibility is crucial for UHV systems, as common materials can become significant gas sources through outgassing. The following table details essential materials and their functions in UHV applications:

Table 4: UHV-Compatible Materials and Research Reagents

| Material/Component | Function in UHV System | Key Properties | Common Examples |

|---|---|---|---|

| Austenitic Stainless Steel | Chamber construction, tubing, flanges | Low vapor pressure, low magnetic permeability, forms protective oxide layer | 304, 304L, 316, 316LN grades [1] |

| Oxygen-Free High-Conductivity Copper | Gaskets, electrical feedthroughs | High purity, minimal hydrogen content, deformable for sealing | OFHC copper for gaskets in ConFlat flanges [1] [5] |

| Ceramics (Alumina, Macor) | Electrical and thermal insulation | High electrical resistivity, low outgassing, machinable | Al₂O₃ for electrical feedthroughs [1] |

| Fluoropolymers | Limited use for specific applications | Extremely low outgassing (when properly baked) | PTFE, PEEK in minimal quantities [1] [3] |

| Metal Seals | Demountable vacuum connections | Plastic deformation creates hermetic barrier | Copper gaskets for ConFlat flanges [1] [3] |

Materials to avoid in UHV systems include most plastics (except specialized UHV-compatible grades), organic compounds, standard carbon steel, and high-vapor-pressure metals like zinc and cadmium [1]. These materials either outgas significantly or have high vapor pressures that prevent the attainment of UHV.

Advanced UHV Experimental Protocol: Surface Defect Characterization

UHV-FT-IR Protocol for Catalyst Surface Analysis

Fourier Transform Infrared (FT-IR) spectroscopy under UHV conditions provides powerful capabilities for characterizing catalytic surfaces. The following protocol, adapted from research on titanium dioxide (TiO₂) surfaces, demonstrates how UHV enables precise quantification of surface defects [7]:

Step 1: Sample Preparation

- Single crystal or powder samples are mounted on UHV-compatible holders.

- For powder samples (e.g., TiO₂ nanoparticles), press the powder against a gold-coated stainless steel grid (0.5 cm × 0.5 cm) to ensure mechanical stability and thermal contact [7].

Step 2: UHV Transfer and Surface Preparation

- Transfer the sample into the UHV system via a load-lock chamber to maintain the main chamber's UHV conditions.

- Clean single crystal surfaces (e.g., r-TiO₂(110)) using multiple cycles of Ar⁺ ion sputtering followed by annealing at 800 K in oxygen atmosphere [7].

- For powder samples, heat at 700 K in UHV to remove contaminants such as water and hydroxyl groups [7].

Step 3: Surface Defect Engineering

- Create a "perfect" (low-defect) surface by exposing the sample to a small amount of oxygen in UHV at 110 K [7].

- Generate oxygen vacancies through controlled sputtering or annealing at elevated temperatures (900 K) [7].

Step 4: CO Probe Molecule Dosing

- Cool the sample to 110 K to enhance CO adsorption.

- Expose the surface to carbon monoxide (CO) at controlled doses.

- CO molecules bind preferentially to specific Ti sites, with distinct vibrational frequencies indicating their proximity to oxygen vacancies [7].

Step 5: FT-IR Spectroscopy Measurement

- Acquire IR spectra using a vacuum FT-IR spectrometer with optical path evacuated to avoid atmospheric interference.

- For single crystals, use Infrared Reflection Absorption Spectroscopy (IRRAS) at grazing incidence (80° to surface normal) [7].

- For powder samples, use transmission geometry [7].

- Collect 1024 scans at 4 cm⁻¹ resolution for adequate signal-to-noise ratio [7].

Step 6: Defect Density Calculation

- Identify absorption bands in the CO-stretching region (approximately 2170-2190 cm⁻¹).

- The band at ~2188 cm⁻¹ corresponds to CO on regular Ti sites, while the band at ~2178 cm⁻¹ indicates CO adjacent to oxygen vacancies [7].

- Calculate oxygen vacancy concentration from the intensity ratio of these bands, considering maximum CO coverage (0.5 monolayer at 110 K) [7].

This protocol enables quantification of defect densities with remarkable precision (approximately 8-10% for reduced TiO₂ surfaces), demonstrating the critical role of UHV in establishing the relationship between surface defects and catalytic activity [7].

The UHV regime, defined by pressures below 10⁻⁷ mbar, creates unique environmental conditions essential for modern surface science. The exceptionally long mean free paths and dramatically reduced molecular fluxes in UHV enable both the preservation of atomically clean surfaces and the application of electron- and ion-based analytical techniques that would be impossible at higher pressures. Successful implementation of UHV technology requires meticulous attention to system design, material selection, and specialized protocols such as bake-out procedures. As demonstrated in the UHV-FT-IR protocol for catalyst characterization, the controlled environment of UHV systems provides unprecedented insights into surface structure and reactivity, forming the foundation for advancements in materials science, catalysis, and semiconductor technology. The continued refinement of UHV preparation protocols and analytical methods promises to further expand our understanding of surface phenomena at the molecular level.

In the realm of ultra-high vacuum (UHV) surface preparation protocol research, outgassing presents a fundamental challenge that directly impacts experimental integrity and system performance. Outgassing is the process whereby gases previously trapped, dissolved, or absorbed within materials are released upon exposure to vacuum conditions [8] [9]. This phenomenon occurs through several physical mechanisms including desorption, diffusion, permeation, and vaporization [10]. In UHV environments, defined as operating between 10⁻⁷ and 10⁻¹² mbar [11], outgassing becomes the dominant gas load, potentially contributing up to 100% of the total gas load in a leak-tight system [10].

The criticality of managing outgassing stems from its potential to compromise UHV processes through multiple pathways. Released volatiles can contaminate pristine surfaces, interfere with sensitive instrumentation, and elevate system pressure beyond operational thresholds [8] [9]. For researchers in surface science and drug development, uncontrolled outgassing can lead to unreliable experimental results, compromised sample purity, and reduced equipment lifespan. Understanding the sources, impacts, and control strategies for outgassing is therefore not merely a technical consideration but a foundational requirement for rigorous UHV research.

Fundamental Outgassing Mechanisms

Outgassing in UHV systems proceeds through four primary physical mechanisms, each with distinct characteristics and implications for system design:

- Desorption: The release of gas molecules bound to material surfaces, typically driven by thermal, electric, or photonic stimulation [8] [10]. This mechanism predominantly affects surface-adsorbed species such as water vapor, which constitutes 75-95% of the gas load at 10⁻³ mbar [10].

- Diffusion: The migration of gaseous molecules from a material's interior structure to its surface, driven by concentration gradients [8] [12]. This process is temperature-dependent and can persist long after initial pump-down.

- Permeation: The movement of gas molecules from the external atmosphere through the bulk material to the vacuum interior [8] [10]. This mechanism becomes particularly significant in Extreme High Vacuum (XHV) conditions below 10⁻¹² mbar [11].

- Vaporization: The release of molecules directly from the material surface itself [8] [10]. While negligible for most metals at typical operating temperatures, vaporization can be significant for polymers and composite materials.

Material-Specific Outgassing Rates

The propensity of materials to outgas varies dramatically across material classes. The following table summarizes typical outgassing rates for common engineering materials after one hour of pumping, illustrating the significant advantages of proper material selection:

Table 1: Typical Outgassing Rates for Common Engineering Materials [10]

| Material | Average Outgassing Rate (mbar·L·s⁻¹·cm⁻²) |

|---|---|

| Titanium | 1.0 × 10⁻⁸ |

| Pyrex | 9.9 × 10⁻⁹ |

| Copper | 2.3 × 10⁻⁸ |

| Stainless Steel | 1.9 × 10⁻⁷ |

| Aluminum | 3.0 × 10⁻⁷ |

| Viton A | 1.1 × 10⁻⁶ |

| PTFE | 1.4 × 10⁻⁶ |

| PVC | 3.2 × 10⁻⁶ |

| Neoprene | 4.0 × 10⁻⁵ |

These quantitative differences highlight why metals and glasses are preferred in UHV applications, while elastomers and plastics require careful consideration and treatment. For instance, stainless steel—a common UHV chamber material—has an outgassing rate nearly three orders of magnitude lower than Viton A, a frequently used elastomer [10].

Impacts of Outgassing on UHV Surface Research

Contamination and Surface Effects

In UHV surface preparation protocols, the primary concern with outgassing is molecular contamination of carefully prepared surfaces. Released volatiles can condense on critical surfaces, forming monolayers that alter surface chemistry and interfere with experimental results [8] [9]. For drug development research involving surface characterization techniques, even sub-monolayer contamination can significantly impact binding studies and surface interaction analyses.

The composition of outgassed species evolves with vacuum level. While water vapor dominates at higher vacuum pressures (10⁻³ mbar), hydrogen and carbon monoxide become predominant in UHV conditions (below 10⁻⁹ mbar) [10]. This shifting composition presents distinct challenges for different research applications, requiring tailored mitigation strategies.

System Performance Degradation

Beyond direct surface contamination, outgassing imposes significant operational constraints on UHV systems:

- Pressure Limitations: Outgassing establishes the ultimate base pressure achievable in a system, potentially limiting the vacuum quality essential for sensitive experiments [13].

- Pump-down Time Extension: The additional gas load from outgassing materials prolongs the time required to reach operational vacuum levels, reducing research throughput [14].

- Pumping Capacity Requirements: Systems with high outgassing materials require increased pumping capacity to maintain target pressures, elevating capital and operational costs [15].

Table 2: Dominant Gas Species by Pressure Range [10]

| Pressure (mbar) | Major Gas Load Composition |

|---|---|

| 10⁻³ | Water vapour (75-95%), N₂, O₂ |

| 10⁻⁶ | H₂O, CO, CO₂, N₂ |

| 10⁻⁹ | CO, H₂, CO₂, H₂O |

| 10⁻¹⁰ | H₂, CO |

| 10⁻¹¹ | H₂ |

Quantitative Assessment and Measurement Protocols

Standardized Testing Methods

Quantitative assessment of outgassing is essential for material selection and process validation in UHV research. The most widely recognized standard for evaluating outgassing is ASTM E595-07, which specifies testing at 125°C under a pressure of 10⁻⁶ Torr for 24 hours [9] [16]. This test measures two critical parameters:

- Total Mass Loss (TML): The percentage of original mass lost during testing, with NASA typically requiring <1.0% for space applications [9].

- Collected Volatile Condensable Materials (CVCM): The percentage of original mass that recondenses on nearby surfaces, with limits <0.1% for critical applications [9] [16].

Additional parameters sometimes measured include Water Vapor Regained (WVR) and Recovered Mass Loss (RML) [9]. For UHV applications, these standardized tests provide comparable data for informed material selection.

Direct Outgassing Rate Measurement

For research-grade validation, direct measurement of outgassing rates provides essential data for system design. The outgassing rate is expressed as the quantity of gas (pressure × volume) per unit surface area per unit time, with common units being Torr·L·s⁻¹·cm⁻² or mbar·L·s⁻¹·cm⁻² [13].

Two principal methods are employed for direct outgassing rate measurement:

- Rate-of-Rise Method: The chamber is evacuated, isolated from pumps, and the pressure increase over time (dP/dt) is measured. The outgassing rate is then calculated as ( \frac{V}{A} \times \frac{dP}{dt} ), where V is volume and A is surface area [13].

- Conductance Method: A pump remains connected to the vessel but is separated by a known conductance C. Measuring the pressure difference across this conductance allows calculation of the outgassing rate [13].

The conductance method generally provides faster measurements but requires accurate characterization of the conductance value [13]. Both methods are susceptible to measurement errors from gauge calibration, especially when using ionization gauges that can themselves outgas or act as pumps under certain conditions [13].

Diagram 1: Outgassing rate measurement workflow (76 characters)

Control Strategies and Mitigation Protocols

Material Selection and Surface Treatments

The most fundamental strategy for outgassing control begins with appropriate material selection and surface preparation:

- Material Choice: Prefer metals (stainless steel, titanium, copper) and ceramics over polymers and elastomers [10]. When polymers are unavoidable, select low-outgassing formulations specifically designed for UHV applications [9].

- Surface Polishing: Electropolishing stainless steel can reduce outgassing by a factor of 30, while mechanical polishing provides a factor of 50 reduction compared to untreated surfaces [17].

- Passivation Coatings: Apply barrier coatings via Chemical Vapor Deposition (CVD), Physical Vapor Deposition (PVD), or sputter coating at elevated temperatures (200-500°C) to create barriers against contaminant adsorption and permeation [17]. Non-Evaporable Getter (NEG) coatings can actively pump gases (H₂, CO, H₂O, O₂, N₂) but require periodic thermal activation [17].

Table 3: Effectiveness of Surface Treatments on Stainless Steel [17]

| Treatment Method | Reduction Factor | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Electropolishing | 30× | Replaces amorphous surface layer with ordered oxide layer |

| Mechanical Polishing | 50× | Effective first treatment for gross contaminant removal |

| Bakeout (250°C for 30 hours) | >70,000× | Most effective for water vapor and hydrogen removal |

Baking and Thermal Processing Protocols

Thermal processing represents the most effective method for reducing outgassing in UHV systems:

- Low-Temperature Baking (100-250°C): Effectively removes water vapor and other weakly-bound surface species [17]. Typical protocols involve gradual temperature ramping (1-5°C/minute) with sustained baking for 24-48 hours under vacuum.

- High-Temperature Baking (250-1000°C): Required for hydrogen removal from the material bulk [17]. These aggressive protocols are typically applied during initial chamber preparation rather than routine maintenance.

- Vacuum Pre-baking of Components: Individually baking components before assembly prevents contamination of the main chamber. For electronic components like PCBs, IPC-1601 specifies baking at 100-125°C to remove moisture before soldering [12] [16].

The duration and temperature of baking protocols involve trade-offs between outgassing reduction and practical constraints. Longer and repeated baking cycles yield progressively lower outgassing rates, with demonstrable improvements even after hundreds of hours of cumulative baking [17].

Cleaning and Handling Procedures

Meticulous cleaning and handling procedures are essential for maintaining low-outgassing surfaces:

- Sequential Cleaning Protocol:

- Clean Handling Practices: Use powder-free latex gloves to prevent fingerprint contamination, which can take several days to desorb [17] [11]. Limit exposure to atmospheric moisture during assembly.

- System Venting Practices: When venting to atmosphere, use dry nitrogen rather than air to minimize water vapor adsorption [17]. Purging with dry gas can significantly reduce subsequent pump-down times.

Diagram 2: Systematic approach to outgassing control (76 characters)

The UHV Researcher's Toolkit

Essential Materials and Reagents

Successful UHV surface preparation requires carefully selected materials with documented low-outgassing characteristics:

Table 4: Essential Research Materials for UHV Applications

| Material/Component | Function | UHV-Specific Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Stainless Steel (316L) | Chamber construction, fixtures | Low iron content, electropolished finish |

| Copper Gaskets | Static sealing for CF flanges | Single-use, proper torque application |

| OFHC Copper | Thermal transfer components | High purity minimizes outgassing |

| Titanium | Critical components | Excellent UHV compatibility, low hydrogen permeation |

| Pyrex/Borosilicate Glass | Viewports, electrical feedthroughs | Fire-polished edges reduce outgassing |

| Low-Outgassing Epoxies | Component bonding | Formulated to meet ASTM E595 requirements |

| Non-Evaporable Getter (NEG) | Active surface pumping | Requires thermal activation, pumps H₂, CO, CO₂ |

Specialized Equipment for Outgassing Management

Beyond standard UHV equipment, several specialized tools enhance outgassing control:

- Helium Leak Detector (HLD): Essential for detecting leaks as small as 10⁻¹² mbar·L·s⁻¹, distinguishing between true leaks and outgassing [11].

- Residual Gas Analyzer (RGA): Mass spectrometer for identifying specific outgassing species and quantifying their partial pressures [13].

- High-Temperature Bakeout Ovens: Capable of sustained operation up to 500°C for component preparation before UHV installation [17].

- Quartz Crystal Microbalance (QCM): Measures molecular contamination rates in real-time by detecting mass changes on a vibrating crystal [9].

- Electropolishing Setup: For creating smooth, low-outgassing surface finishes on metallic components [17].

Outgassing remains a critical challenge in UHV surface preparation protocols, directly impacting the integrity of scientific research across surface science, materials engineering, and drug development. Through systematic implementation of the control strategies outlined in these application notes—including rigorous material selection, comprehensive surface treatments, optimized baking protocols, and meticulous cleaning procedures—researchers can achieve the stable, clean vacuum environments essential for reliable surface studies.

The quantitative assessment methods and standardized protocols detailed herein provide a foundation for developing robust UHV research capabilities. As UHV technology advances toward ever-lower pressure regimes, continued attention to outgassing fundamentals will remain essential for pushing the boundaries of surface-sensitive research and development.

Ultra-high vacuum (UHV) systems, operating at pressures below 10⁻⁹ mbar, are critical for a wide range of scientific and industrial applications where molecular-level contamination must be eliminated [18] [19]. These environments are essential for processes such as semiconductor manufacturing, surface science research, and particle accelerator operations, where even monolayer formation can compromise results [18]. The selection of appropriate construction materials represents a fundamental consideration in UHV design, directly impacting base pressure attainment, contamination control, operational efficiency, and long-term system reliability. This application note provides a detailed comparative analysis of three principal materials—stainless steel, aluminum, and silicon—within the context of UHV surface preparation protocols. We examine their intrinsic material properties, performance characteristics in vacuum environments, and provide standardized preparation methodologies to achieve UHV-compatible surfaces, specifically framed for research applications in drug development and surface science.

Comparative Material Analysis

The selection of materials for UHV components involves balancing physical properties, chemical characteristics, and practical fabrication considerations. Table 1 provides a quantitative comparison of key properties for stainless steel, aluminum, and silicon relevant to UHV performance.

Table 1: Quantitative Comparison of UHV Material Properties

| Property | Stainless Steel (304/316) | Aluminum (6061) | Silicon |

|---|---|---|---|

| Outgassing Rate (after treatment) | Low (Requires bake-out) | Very Low (With proper treatment) | Extremely Low |

| Thermal Conductivity (W/m·K) | 15 - 20 | 150 - 200 | 130 - 150 |

| Coefficient of Thermal Expansion (10⁻⁶/K) | 16 - 18 | 23 - 24 | 2.6 |

| Machinability | Moderate (Cost: 5.5x aluminum) [18] | Excellent | Poor (Brittle) |

| Magnetic Permeability | Varies (316L is low) | Non-Magnetic | Non-Magnetic |

| Primary UHV Application | General chambers, beamlines, flanges | Cluster tools, cryogenic shields, structural frames | Specialist components, wafer substrates |

Material-Specific Advantages and Limitations

Stainless Steel (304/316L): This is a traditional choice for UHV chambers and components. Its primary advantage lies in its well-understood fabrication and welding techniques. However, it is a "notorious water sponge," requiring prolonged bake-out cycles at temperatures of 150-250°C to desorb water vapor and achieve ultimate pressure [18]. Furthermore, its low thermal conductivity can be a limitation for applications requiring rapid thermal cycling or efficient heat dissipation. Concerns also exist regarding potential iron and chromium contamination in sensitive processes [18].

Aluminum (e.g., 6061, 6063): Aluminum offers superior thermal conductivity, which facilitates faster pump-down and bake-out cycles compared to stainless steel [18]. Its natural non-magnetic property is advantageous for applications involving magnetic fields. A key benefit is its excellent machinability, allowing for the creation of complex, compact components from a single plate, saving valuable cleanroom space [18] [20]. The main challenge historically has been achieving a UHV-compatible surface, as-machined or extruded surfaces have a porous, contaminated oxide layer that must be removed and reformed [18].

Silicon: While not a common structural material, silicon is the primary substrate in many semiconductor processing tools integrated into UHV systems. Its ultra-low outgassing and minimal contaminating potential are major benefits [20]. Its extreme brittleness and poor machinability limit its use to specific roles, such as viewport windows for infrared applications or specialized sample holders [21].

Surface Preparation Protocols for UHV Compatibility

Achieving UHV conditions requires not only selecting the right material but also applying rigorous surface treatments to minimize outgassing and vapor pressure. The following protocols outline standardized methodologies for each material.

Aluminum Surface Treatment Protocol

The native oxide layer on aluminum is porous and contaminated, requiring complete removal and reformation [18].

- Initial Degreasing: Clean components with a detergent in an ultrasonic bath or with modified alcohols to remove organic contaminants like grease and fingerprints [22].

- Alkaline Cleaning: Immerse the component in an alkaline solution (e.g., 5-10% NaOH) at 50-70°C for 5-15 minutes. This strips the existing, thick aluminum oxide layer and surface impurities [18].

- Rinsing: Immediately after alkaline cleaning, rinse thoroughly with deionized water to remove all traces of the cleaning agent.

- Oxide Reformation: Allow the clean, exposed aluminum surface to form a new native oxide in a clean, dry air environment. This newly formed oxide layer will be thin, dense, and non-porous, rendering the surface UHV-compatible [18].

- Drying: Use forced clean, dry air or nitrogen to ensure the component is completely dry before assembly. Trapped water is a significant source of vacuum contamination [22].

Stainless Steel Surface Treatment Protocol

The goal for stainless steel is to remove contaminants and passivate the surface to reduce its tendency to absorb water.

- Solvent Cleaning: Use non-aqueous solvents like modified alcohols to dissolve and remove organic contaminants and machining oils from the surface [22].

- Electropolishing (Recommended): This process removes a surface layer (e.g., 150 µm), eliminating the subsurface layer damaged by machining which contains voids, dislocations, and impurities. This results in a smooth, flawless surface with low effective surface area and minimal residual stress, drastically reducing outgassing [22].

- Passivation: Treat the surface with acids (e.g., nitric acid) to remove free iron particles and form a stable, protective chromium-rich oxide layer that enhances corrosion resistance.

- Final Rinsing and Drying: Rinse extensively with high-purity water, preferably deionized and filtered. Dry with clean, dry nitrogen or air [22].

- UHV Bake-Out: As a final step in situ, bake the entire assembled system under vacuum to 150-250°C for 24-48 hours to desorb the primary contaminant: water vapor [18].

Silicon Surface Treatment Protocol

Silicon preparation focuses on achieving extreme chemical cleanliness and surface perfection.

- RCA Standard Clean: This is a classic two-step cleaning procedure for silicon wafers.

- SC-1 (Standard Clean 1): A mixture of ammonium hydroxide, hydrogen peroxide, and water (typically 1:1:5) at 70-80°C. This removes organic contaminants.

- SC-2 (Standard Clean 2): A mixture of hydrochloric acid, hydrogen peroxide, and water (typically 1:1:6) at 70-80°C. This removes ionic and metallic contaminants.

- HF Dip: A brief immersion in a diluted hydrofluoric (HF) acid solution to strip the native silicon oxide layer, leaving a hydrogen-terminated, hydrophobic surface.

- Rinsing and Drying: Rinse with ultra-pure deionized water and use a spin-rinse dryer or Marangoni drying to prevent watermarks or particle deposition.

The following workflow diagram illustrates the decision-making process for selecting and preparing these materials for a UHV system.

Implementation in Research Systems

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential UHV Materials and Reagents

Successful UHV surface preparation requires the use of specific, high-purity reagents and materials. Table 2 lists key items and their functions in the protocols described.

Table 2: Research Reagent Solutions for UHV Surface Preparation

| Reagent / Material | Function in UHV Preparation | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| High-Purity Alkaline Solutions | Strips porous native oxide from aluminum to allow a dense, new oxide to form. | Critical for creating UHV-compatible aluminum surfaces [18]. |

| Modified Alcohol Solvents | Dilutes and removes organic contaminants (oils, greases) without severe toxicity. | Preferred over aggressive solvents for initial degreasing [22]. |

| Electropolishing Electrolytes | Removes subsurface damage layer and smoothens surface, drastically reducing outgassing. | Standard for stainless steel; creates a flawless surface finish [22]. |

| RCA Clean Chemicals (NH₄OH, H₂O₂, HCl) | Removes organic, ionic, and metallic contaminants from silicon surfaces. | Industry-standard for silicon wafer cleaning. |

| Hydrofluoric Acid (HF) | Strips native oxide from silicon, leaving a hydrogen-terminated surface. | Requires extreme caution and specialized equipment for handling. |

| High-Purity Aluminum Foil | Used for storing and transporting prepared samples; provides a clean barrier. | Alternative to plastic containers which can be sources of contamination [23]. |

| Polyethylene Gloves | Handles samples and components without introducing silicone contamination. | Other gloves contain silicones that are common surface contaminants [23]. |

Ancillary Component Integration

UHV systems incorporate various components whose material selection is equally critical. Motorized positioning stages used within the vacuum must be constructed from materials like stainless steel, aluminum, or titanium, with special attention to avoiding conventional lubricants that outgas hydrocarbons [19]. Similarly, viewports require careful material pairing; for example, fused silica is used for UV laser applications, sapphire for broad transmission from UV to near-IR, and zinc selenide for IR and thermal imaging [21]. Conductive coatings such as Indium Tin Oxide (ITO) can be applied to viewports to prevent electrostatic charging [21].

The selection between stainless steel, aluminum, and silicon for a UHV system is a strategic decision guided by application-specific requirements. Stainless steel offers proven reliability for general chambers but imposes operational penalties due to its high water retention and need for prolonged baking. Aluminum presents a high-performance alternative with superior thermal management and machinability, provided its surface is correctly treated to form a UHV-compatible oxide layer. Silicon, while not a structural material, is unmatched for its purity in substrate and specialist optic applications. The standardized surface preparation protocols detailed in this note—electropolishing and passivation for stainless steel, alkaline cleaning and oxide reformation for aluminum, and the RCA clean for silicon—are foundational to achieving the requisite surface purity for UHV operation. By adhering to these material selection principles and preparation protocols, researchers and engineers can design and maintain UHV systems that meet the stringent contamination-control standards required for advanced research in drug development, semiconductor processing, and surface science.

Surface oxide layers present a fundamental duality in ultra-high vacuum (UHV) surface science and materials engineering. These naturally occurring or synthetically grown films serve as essential protective barriers against corrosion and degradation while simultaneously functioning as potential traps for chemical contaminants that compromise surface purity and experimental integrity. Within the context of UHV surface preparation protocol research, this dual nature necessitates carefully balanced experimental approaches that either exploit the protective qualities of oxide layers or strive for their complete removal and replacement with controlled, pristine films. The strategic management of surface oxides becomes particularly critical for research involving catalytic surfaces, electronic device fabrication, and fundamental surface science studies where even monolayer contamination can dramatically alter experimental outcomes. This application note details protocols for controlling surface oxide layers, providing researchers with methodologies to either preserve their protective function or eliminate their contaminant-trapping potential for UHV-based investigations.

The Dual Nature of Surface Oxides: Protection Versus Contamination

Surface Oxides as Protective Barriers

Surface oxide layers function as protective barriers through several mechanisms that inhibit degradation of the underlying material. In metallic biomaterials such as titanium and its alloys, a thin, retentive oxide film protects the underlying metal from corrosion, preventing the release of toxic metal particles that could evoke adverse biological reactions [24]. This protective function is crucial for implant longevity, as corrosion products can lead to osteolysis and eventual implant failure [24].

In photoelectrochemical (PEC) systems, atomic layer deposition (ALD) of protective oxide layers such as TiO₂ significantly enhances electrode stability by preventing chemical/electrolyte/photo-corrosion of base materials like Cu₂O [25]. These protection layers reduce charge recombination at the electrode-electrolyte interface, thereby enhancing PEC reaction kinetics. The protective efficacy depends critically on layer thickness, with studies indicating that >30-nm-thick TiO₂ films provide stable performance, although excessive thickness can detrimentally impact light absorption capabilities [25].

Table 1: Protective Oxide Layers in Different Applications

| Material System | Protective Oxide | Protective Mechanism | Optimal Thickness |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ti6Al4V Implants | Native TiO₂ | Corrosion barrier preventing metal ion release | 2-10 nm (native) |

| Cu₂O Photoelectrodes | ALD TiO₂ | Prevention of photo-corrosion | ~20 nm |

| Hematite Photoanodes | ALD Al₂O₃ | Decreased carrier recombination | ~4 nm |

| AZO Conductive Films | ALD TiO₂ | Prevention of electrolyte penetration | ~10 nm |

Surface Oxides as Contamination Traps

Despite their protective benefits, surface oxides readily function as contamination traps through various mechanisms. The highly porous nature of certain anodic oxides, such as those created through micro-arc oxidation (MAO), creates abundant sites for contaminant adsorption and entrapment [26]. In UHV surface studies of materials like MoS₂, surface oxides and residual contaminants present significant analytical challenges, with carbonaceous contamination persisting even under UHV conditions [27].

The semiconductor industry faces particular challenges with oxide-related contamination, where fixed contamination forms strong electrostatic or chemical bonds with surface oxides [28]. This fixed contamination differs from smearable contamination, which can be removed by simple wiping, whereas fixed contamination typically requires harsh removal techniques such as chemical dissolution or scabbling [28]. The effectiveness of decontamination processes is quantified by the decontamination factor (DF), calculated as the ratio of contamination levels before and after decontamination [28].

Quantitative Analysis of Oxide Layer Properties

The protective and contaminant-trapping properties of surface oxides correlate directly with their physical and chemical characteristics. Systematic analysis of these parameters enables researchers to predict and control oxide behavior in UHV environments.

Table 2: Quantitative Characterization of Surface Oxide Layers

| Characterization Parameter | Analytical Technique | Significance for UHV Applications |

|---|---|---|

| Oxide Thickness | ESCA/XPS, Ellipsometry | Determines barrier effectiveness and electronic properties |

| Elemental Composition | ESCA, EDS, AES | Identifies doping elements and contaminant incorporation |

| Surface Roughness | AFM, Profilometry | Affects contaminant adhesion and surface area |

| Crystalline Structure | XRD, TEM | Influences chemical stability and electronic properties |

| Wettability/Contact Angle | Goniometry | Predicts interfacial interactions with contaminants |

| Surface Net Charge | AFM Force Measurement | Determines electrostatic contaminant attraction |

Research on Ti6Al4V alloys demonstrates that surface treatments significantly alter oxide properties. Radiofrequency plasma glow discharge (RFGD) treatment in oxygen increases oxide wettability and net positive surface charge at pH values below 6, while creating a higher net negative surface charge at physiological pH (7-8) compared to untreated controls [24]. Heat treatment to 600°C produces substantial topographic changes, creating nanostructured oxide elevations approximately 50-100 nm in diameter with a three-fold increase in roughness compared to untreated surfaces [24].

Experimental Protocols for Surface Oxide Control

Protocol 1: Atomic Layer Deposition of Protective Oxide Coatings

Principle: Atomic layer deposition enables conformal, pinhole-free oxide coatings with precise thickness control at the atomic scale, providing optimal protection for underlying materials while minimizing contaminant trapping sites.

Materials:

- Precursor Materials: Trimethylaluminum (TMA) for Al₂O₃, titanium tetrachloride (TiCl₄) or tetrakis(dimethylamido)titanium (TDMAT) for TiO₂

- Oxygen Source: H₂O, O₃, or O₂ plasma

- Inert Carrier Gas: High-purity N₂ or Ar

- Substrate: Pre-cleaned material (Si wafer, metal foil, or specialized substrates)

- ALD Reactor: Thermal or plasma-enhanced system with precise temperature and pressure control

Procedure:

- Substrate Preparation: Clean substrate using appropriate protocol (RCA cleaning for Si, electrochemical polishing for metals) to remove native contaminants.

- Reactor Loading: Transfer substrate to ALD reactor under controlled atmosphere to minimize air exposure.

- System Conditioning: Pump reactor to base pressure (<10⁻³ Torr) and stabilize at deposition temperature (100-300°C depending on material).

- ALD Cycling: a. Precursor Dose: Introduce metal precursor pulse (0.1-0.5 s) followed by purging with inert gas (10-30 s) b. Reactant Dose: Introduce oxygen source pulse (0.1-0.5 s) followed by purging (10-30 s) c. Cycle Repetition: Repeat sequence until desired thickness achieved (growth per cycle typically 0.5-1.5 Å)

- Post-deposition Annealing: Optional thermal treatment (300-500°C in O₂ or inert atmosphere) to improve crystallinity and stability.

Quality Control:

- Verify thickness using spectroscopic ellipsometry

- Confirm composition using XPS or AES

- Check for pinholes using electrochemical tests or SEM inspection

- Validate conformality using trench structures or high-aspect-ratio substrates

Protocol 2: Mechanical Exfoliation of Surface Oxides and Contaminants

Principle: Mechanical exfoliation provides a rapid method for removing surface oxides and contaminants from layered materials, producing atomically clean surfaces for UHV analysis.

Materials:

- Bulk crystalline material (MoS₂, HOPG, etc.)

- Exfoliation tapes: Regular acrylic, heat-resistant, or double-sided conductive tapes

- Substrates: SiO₂/Si wafers, gold-coated Cu-Be foils

- Optical microscope for sample inspection

- UHV transfer system

Procedure:

- Tape Selection: Choose appropriate exfoliation tape based on material properties and desired surface quality.

- Exfoliation Technique: a. Standard Method: Apply tape over entire sample surface and peel off slowly from one end b. Edge-initiated Method: Attach tape to one sample edge and peel parallel to sample plane c. Iterative Method: Repeatedly fold and peel tape to progressively thin material

- Surface Transfer: Press freshly-exposed material surface against clean substrate

- Tape Removal: Carefully peel back tape at 180° angle to leave thin flakes on substrate

- UHV Transfer: Immediately transfer exfoliated sample to UHV chamber (<1×10⁻⁹ Torr) to minimize contamination

Optimization Notes:

- Gold-coated Cu-Be foils provide optimal electrical contact for spectroscopic analysis

- Ambient condition control (humidity <30%) improves reproducibility

- Parallel peeling technique produces larger, cleaner terraces compared to perpendicular peeling

Protocol 3: UHV Surface Rejuvenation via Sputter-Annealing Cycles

Principle: Sequential noble gas ion sputtering and thermal annealing effectively remove surface oxides and contaminants while enabling controlled oxide regrowth under clean conditions.

Materials:

- UHV System: Base pressure <1×10⁻¹⁰ Torr with sputter gun and sample heating capability

- Sputter Gas: High-purity Ar⁺, Ne⁺, or Kr⁺ (99.999%)

- Sample Holder: Direct resistive heating or electron bombardment heating capability

- Surface Analysis: In-situ AES, XPS, or LEED for process monitoring

Procedure:

- Initial Characterization: Acquire reference survey spectra (AES/XPS) to determine initial surface composition.

- Sputter Parameters: a. Ion Energy: 0.5-3 keV (lower energies minimize surface damage) b. Ion Current: 1-20 μA/cm² (optimize for removal rate versus surface roughness) c. Incidence Angle: 45-70° (grazing angles enhance sputter yield) d. Duration: 10-60 minutes (until contaminant signals minimized)

- Thermal Annealing: a. Temperature Ramping: Gradual increase to target temperature (2-5°C/s) b. Annealing Conditions: 400-800°C for 5-30 minutes in UHV c. Controlled Oxidation: Optional exposure to high-purity O₂ (1×10⁻⁶ - 1×10⁻⁴ Torr) for controlled oxide growth

- Cycle Repetition: Typically 3-10 sputter-anneal cycles until desired surface quality achieved

Application-Specific Parameters:

- MoS₂: 1 keV Ar⁺, 450°C annealing [27]

- Ti Alloys: 2 keV Ar⁺, 600°C annealing [24]

- Si: 0.5-1 keV Ar⁺, 850°C flash annealing

Research Reagent Solutions for Surface Oxide Management

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Surface Oxide Control

| Reagent/Chemical | Function | Application Notes | Safety Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Trimethylaluminum (TMA) | ALD precursor for Al₂O₃ | Moisture-sensitive; requires anhydrous handling | Pyrophoric; strict exclusion of air/water |

| Titanium tetrachloride (TiCl₄) | ALD precursor for TiO₂ | Corrosive; produces HCl byproduct | Moisture-sensitive; corrosive fumes |

| High-purity O₂ gas (99.999%) | Oxidation source | For controlled oxidation and plasma processes | Oxidizer; compatible with UHV systems |

| Ar⁺ sputter gas (99.999%) | Surface cleaning | Low damage at 0.5-1 keV; higher yields at 2-3 keV | Inert; high-pressure cylinder handling |

| AgNO₃ | Antimicrobial incorporation | 0.5 mM in MAO electrolytes for antibacterial properties | Oxidizer; toxic if ingested |

| ZnCl₂ | Antimicrobial incorporation | 5.0 mM in MAO electrolytes for sustained protection | Moisture-sensitive; corrosive |

| Calcium glycerophosphate | MAO electrolyte component | 100 mM with calcium acetate for porous oxides | Irritant; use with PPE |

| Nitric acid (40%) | Passivation treatment | ASTM-F86 protocol for Ti alloys [24] | Strong oxidizer; severe corrosion hazard |

Visualization of Surface Oxide Control Strategies

Surface Oxide Management Decision Workflow

The strategic management of surface oxide layers represents a critical capability in UHV surface science, requiring researchers to navigate the delicate balance between exploiting their protective functions and mitigating their contaminant-trapping potential. The protocols detailed in this application note provide methodologies for either preserving protective oxide layers or eliminating them entirely for pristine surface studies. As surface science advances toward increasingly sensitive measurements and applications in quantum materials and single-atom catalysis, the precise control of surface oxide properties will continue to grow in importance. Researchers must select the appropriate strategy based on their specific application requirements, whether prioritizing the corrosion resistance offered by engineered oxide layers or the atomic-level cleanliness achieved through aggressive oxide removal techniques.

Within the broader context of UHV surface preparation protocol research, the achievement of pristine vacuum conditions is a prerequisite for reliable experimental outcomes. Ultra-High Vacuum (UHV), defined as the pressure range between 10⁻⁷ and 10⁻¹² mbar, is characterized by an environment where the dominant gas load originates from the release of gases from the chamber walls and internal components themselves, a process known as outgassing [15] [11]. To reach and maintain such extreme vacuum levels, the system design must aggressively minimize all potential gas sources. This application note details the fundamental principles and protocols for designing an efficient UHV system, with a specific focus on minimizing internal surface area and eliminating trapped volumes, which are two of the most critical factors in mitigating outgassing and virtual leaks.

Core Design Principles for UHV Systems

The design of a UHV system must adhere to stringent principles that diverge significantly from those of low-vacuum or atmospheric pressure equipment. The following principles are paramount for minimizing the gas load and achieving stable UHV conditions.

Minimizing Internal Surface Area

The rate of outgassing is directly proportional to the available internal surface area of the vacuum chamber [15]. Adsorbed water vapor and other contaminants on these surfaces represent a significant and persistent gas source. Consequently, a primary design goal is to minimize the chamber's internal surface area without compromising its structural integrity or functional volume [15] [11]. This involves using simple, compact geometries and avoiding complex internal baffles or supports wherever possible.

Elimination of Trapped Volumes and Virtual Leaks

Trapped volumes, such as those found in blind tapped holes or unvented gaps between assembled components, act as reservoirs of gas that can only be pumped through very restricted pathways [29]. These are known as virtual leaks and can considerably delay the pump-down process or prevent the system from reaching its base pressure, as the gas in these pockets escapes very slowly [30]. Designs must ensure there are no internal gaps or trapped volumes [15] [11]. A common and critical example is the use of vented screws—screws with a hole drilled through their axis—in blind holes to allow trapped gas to escape directly into the chamber volume where it can be pumped away [29].

Material Selection and Surface Treatment

The choice of materials and their pre-treatment is a fundamental aspect of UHV design. Materials must exhibit low desorption/outgassing rates and be compatible with high-temperature bake-out procedures [15] [30].

- Preferred Materials: Stainless steel, aluminum, titanium, and ceramic (e.g., Al₂O₃) are standard [30] [29]. For electrical insulation, polymers such as PEEK (Polyether Ether Ketone), PTFE (Teflon), and Polyimide (Kapton) are used instead of common plastics, which have high outgassing rates [30] [29].

- Surface Treatments: Electropolishing is the preferred surface treatment for UHV components as it creates a smooth, passivated surface that minimizes surface area and outgassing [15] [29]. Anodizing, a common treatment for aluminum, is typically avoided because its porous structure dramatically increases the effective surface area and can introduce outgassing contaminants from dyes [30].

- Joining and Sealing: All internal welds should be performed from the inside to prevent creating external grooves that can trap contaminants [15] [11]. Furthermore, the number of seals and feedthroughs should be minimized, and metallic seals (e.g., copper gaskets with knife-edge flanges) should be employed instead of elastomer seals for their lower outgassing rates and bake-ability [15].

Table 1: UHV Material and Treatment Selection Guide

| Category | Recommended for UHV | Not Recommended for UHV | Rationale |

|---|---|---|---|

| Structural Metals | Stainless steel, Titanium, certain Aluminum alloys | Brass, Copper-Zinc alloys (CuZn), Cadmium plating | Low outgassing, low vapor pressure, bakeable [30] [29] |

| Electrical Insulators | PEEK, PTFE (Teflon), Polyimide (Kapton), Macor, Sapphire | Standard nylon, PVC, epoxy resins | Withstand bake-out temperatures, very low outgassing rates [30] [29] |

| Surface Treatment | Electropolishing, Blanc (bare) aluminum | Standard anodizing, painted coatings | Smooth, non-porous surface that minimizes area and outgassing [30] |

| Seals | All-Metal Seals (e.g., Copper C-rings) | Elastomer seals (Viton, Buna) | No organic outgassing, can withstand high bake-out temperatures (>150°C) [15] |

Experimental Protocols for UHV System Preparation

The following protocols are essential for preparing and maintaining a UHV system, ensuring that the careful design principles are not compromised during assembly and operation.

Protocol: UHV Component Cleaning and Assembly

This protocol outlines the procedure for preparing components prior to their installation into a UHV system.

3.1.1. Objective: To remove all particulates, chemical residues, and organic contaminants from UHV components without introducing new contaminants. 3.1.2. Materials & Reagents:

- Ultrasonic cleaning bath

- High-purity solvents (e.g., isopropyl alcohol, acetone)

- Climate-controlled drying cabinet or oven

- Class 100 cleanroom or laminar flow box

- Powder-free latex or nitrile gloves [11]

- Clean-room wipes

- Vacuum-compatible packaging materials

3.1.3. Methodology:

- Initial Degreasing: Wipe components with clean-room wipes and a high-purity solvent to remove gross contamination.

- Ultrasonic Cleaning: Submerge components in an ultrasonic bath filled with a suitable high-purity solvent. This is the initial and key step for removing adhered particles and contaminants [30] [29].

- Drying: Transfer the cleaned components to a climate cabinet and dry under a pure nitrogen atmosphere to prevent water condensation and re-contamination [30].

- Assembly: Assemble the stage or component in a cleanroom or laminar flow box by personnel wearing powder-free gloves to prevent fingerprint contamination [11] [30].

- Packaging and Shipping: Pack the assembled unit in vacuum-sealed bags to protect it from dirt, air, and humidity during transport or storage [30].

Protocol: System Bake-Out

3.2.1. Objective: To accelerate the desorption of water vapor and other volatiles from the vast internal surface area of the chamber and components. 3.2.2. Methodology:

- After rough pumping, uniformly heat the entire vacuum system using heating tapes or an oven.

- Typical bake-out temperatures range from 150°C to 250°C for periods of 24 to 48 hours [29]. Specific components, such as all-ceramic piezo actuators, can withstand bake-out temperatures of up to 150°C [29].

- Continue pumping during the bake-out cycle. The increased temperature dramatically increases the outgassing rate, allowing the pumps to remove the vast majority of the adsorbed gas.

- After the bake-out period, allow the system to cool while under vacuum. The resulting pressure will be orders of magnitude lower than before the bake-out.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential UHV Research Reagents and Materials

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for UHV Applications

| Item Name | Function / Application in UHV | Critical Consideration |

|---|---|---|

| PICMA Piezo Actuators | Provides nanometer-precision positioning inside the UHV chamber. Ideal for sample manipulation [29]. | All-ceramic construction eliminates outgassing from polymer insulation; bakeable to 150°C; operates in magnetic fields and cryogenic environments [29]. |

| Vacuum-Compatible Stepper Motors | Drives precision stages for larger travel ranges within the UHV environment [29]. | Features stainless steel housing, high-temperature stable components, and minimal use of organics; designed for pressures down to 10⁻⁹ hPa [29]. |

| Ultrasonic Cleaning Solvents | Used in the multi-stage cleaning process to remove particulate and hydrocarbon contamination from components before assembly [30] [29]. | Must be high-purity grade to prevent residue deposition. Isopropyl alcohol and acetone are common choices. |

| Helium Leak Detector (HLD) | The only credible method for detecting very small leaks (smaller than 10⁻⁷ mbar·l/s) in a UHV system [11]. | Uses helium as a tracer gas and a mass spectrometer for detection. Essential for locating leaks that would prevent the system from reaching base pressure. |

| Metallic Seals (e.g., Copper) | Provides a hermetic seal between UHV flanges (e.g., ConFlat). | Withstands high bake-out temperatures and provides an extreme leak-tight seal with very low outgassing, unlike polymer seals [15]. |

System Design and Pumping Strategy Workflow

The following diagram illustrates the logical workflow for designing and commissioning a UHV system, integrating the principles and protocols discussed above.

Step-by-Step UHV Preparation Protocols for Metals and Semiconductors

Achieving ultra-high vacuum (UHV) conditions is paramount in advanced research and industrial applications, including particle accelerators, synchrotron light sources, and semiconductor manufacturing. The performance and yield in these fields are critically dependent on molecular-level surface cleanliness, where base pressures at or below 10^-9 Torr are required to minimize environmental contamination [18]. Contaminants on vacuum chamber surfaces, such as oils, metallic smut, and porous oxide layers, act as significant sources of outgassing, compromising vacuum integrity and process purity. Consequently, meticulous chemical pre-treatment of chamber components, specifically through etching and de-smutting protocols, forms the foundational step in UHV surface preparation.

This document outlines standardized application notes and experimental protocols for the chemical pre-treatment of two key structural metals: aluminum and stainless steel. The procedures are framed within a broader UHV protocol research context, providing researchers and drug development professionals with validated methodologies to prepare metal surfaces that meet the exacting cleanliness standards required for sensitive vacuum environments. The focus is on reproducible, quantifiable processes that remove impurities and reform passive oxide layers into thin, dense, and non-porous barriers ideal for UHV service [31] [18].

Aluminum Pre-Treatment for UHV

Background and Principles

Aluminum alloys are widely used in UHV systems due to their excellent machinability, low cost, and favorable thermal properties [18]. However, the native oxide layer that forms on aluminum is typically thick (20-200 Å), porous, and contaminated with alloying elements from manufacturing processes [31] [18]. This layer can trap water vapor and other contaminants, leading to persistent outgassing. The goal of chemical pre-treatment is to strip this native oxide and allow a new, thin (angstrom-scale), dense, and non-porous oxide layer to form uniformly [32]. A key challenge is "smut"—finely divided residues of alloying elements like copper, silicon, or iron that remain on the surface after etching and must be removed [31] [33].

Established Protocols from National Laboratories

Research institutions leading in UHV technology have developed and refined several cleaning processes. The following table summarizes several documented procedures for cleaning aluminum alloys.

Table 1: Comparison of Aluminum Cleaning Processes for UHV Service

| Institution (Application) | Aluminum Alloys | Cleaning Method Sequence |

|---|---|---|

| Argonne National Laboratory (Advanced Photo Source) [31] | 6063 | 1. High-pressure spray with 2% Almeco 18.2. Ultrasonic clean with 2% Almeco 18 at 65°C for 10 min.3. Rinse with room-temperature DI water for 10 min.4. Blow dry with hot nitrogen. |

| Brookhaven National Laboratory (National Synchrotron Light Source) [31] | 6000 Series | 1. Ultrasonic clean with Almeco 18 at 77°C.2. DI water rinse at 60°C.3. Buff Out 16000 solution at 77°C.4. Rinse in DI water at 60°C.5. Citrinox solution at 77°C.6. DI water rinse at 60°C.7. Nondenatured ethanol rinse at 25°C.8. Blow dry with air at 25°C. |

| CERN [31] | 6061, 6063 | 1. High-pressure spray jet with Almeco 29 at 60°C.2. High-pressure spray jet with Amklene D Forte.3. Rinse with hot DI water spray jet.4. Dry in air at 80°C. |

| Meyer Tool & Mfg., Inc. (Based on Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory methods) [31] | 6000 & 5000 Series | 1. High-pressure spray with Brulin 1990 GD at 50°C, rinse with DI water.2. Repeat step 1.3. Dry with nitrogen/oil-free air.4. Immerse in 30% phosphoric acid for 30 min, then dry.5. Repeat step 1 twice, then dry. |

Detailed Step-by-Step Experimental Protocol: Alkaline Etch and Acid De-smut

The following is a detailed, bench-level protocol adapted from procedures used at JILA and CERN, which is suitable for smaller components that can be immersed in baths [32].

Figure 1: Aluminum UHV pretreatment workflow.

Step 1: Prepare the Etchant Bath

- Objective: Create a 5.5% (1.39 mol/L) sodium hydroxide (NaOH) solution for etching [32].

- Materials:

- Sodium hydroxide (NaOH) pellets.

- Deionized (DI) or tap water.

- A chemically resistant tank (e.g., stainless steel, polypropylene).

- Heating and stirring apparatus (e.g., hot plate).

- Fume hood.

- Procedure:

- Add 35 L of water to the tank.

- While wearing appropriate Personal Protective Equipment (PPE), slowly add 0.973 kg of NaOH pellets to the water while stirring. Note: This is an exothermic reaction; add slowly to control heat and splashing.

- Heat the solution to a target temperature of 70°C [32]. The solution may become clear as it heats and the NaOH fully dissolves.

Step 2: Alkaline Etch

- Objective: Strip the existing porous oxide layer and a small amount of underlying aluminum.

- Materials: Tongs or baskets resistant to strong bases.

- Procedure:

- Immerse the aluminum component in the heated NaOH bath for 60 seconds [32].

- Agitate gently to ensure uniform etching. A visible reaction with gas evolution should occur.

- Remove the component from the bath. The surface will appear dark or smutty due to residual alloying elements.

Step 3: Rinse (Tap Water)

- Objective: Rapidly terminate the etching reaction and remove residual NaOH.

- Procedure:

- Immediately and thoroughly rinse the component under a stream of tap water [32].

- Ensure all surfaces are thoroughly rinsed to prevent carryover of alkaline solution into the acid bath.

Step 4: Prepare the De-smut Bath

- Objective: Create a 25% nitric acid solution with ammonium bifluoride to remove the smut.

- Materials:

- Concentrated (70%) Nitric Acid (HNO₃).

- Ammonium bifluoride (NH₄HF₂).

- A secondary containment bin made of high-density polyethylene (HDPE) or polypropylene.

- Procedure:

- Add 12.5 L of water to the HDPE bin.

- Slowly and carefully add 5 Liters of 70% Nitric Acid to the water while stirring. Warning: This is a highly exothermic dilution. Pour slowly to avoid localized boiling and splashing. Monitor temperature to ensure it stays below 80°C to avoid damaging the HDPE container.

- Add 25g of ammonium bifluoride (0.1% concentration) to the acid solution [32]. The fluoride acts as a catalyst for the nitric acid's de-smutting action.

Step 5: Acid De-smut

- Objective: Dissolve the metallic smut residues, leaving a bright, clean aluminum surface.

- Procedure:

- Immerse the rinsed aluminum component in the de-smut bath for 5 minutes at room temperature (approx. 20°C) [32].

- The smut should dissolve, and the surface will become visually bright and clean.

Step 6: Rinse (DI Water)

- Objective: Remove all traces of acid and dissolved metallic ions from the surface.

- Procedure:

- Transfer the component to a bath of DI water. Do not leave immersed for more than 10-15 minutes to prevent the initiation of corrosion [32].

- A final rinse with hot DI water, if available, can aid in drying.

Step 7: Dry

- Objective: Remove all moisture without re-contaminating the surface.

- Materials: Filtered, oil-free compressed air or nitrogen.

- Procedure:

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Reagents for Aluminum Pre-Treatment

Table 2: Essential Reagents for Aluminum UHV Pre-Treatment

| Reagent/Solution | Function | Application Note |

|---|---|---|

| Sodium Hydroxide (NaOH) | Strong alkaline etchant. Removes the native aluminum oxide layer and underlying aluminum. | Concentration and temperature must be controlled to prevent over-etching and excessive smut formation [32]. |

| Nitric Acid (HNO₃) | Oxidizing acid. Removes metallic "smut" (e.g., copper, silicon) left after alkaline etching and passivates the surface [33]. | Produces a thin, dense oxide layer. Often used in concentrations of 20-25% [32]. |

| Ammonium Bifluoride (NH₄HF₂) | Source of fluoride ions. Acts as an activator for nitric acid, enhancing its ability to dissolve certain types of smut [32]. | A small concentration (e.g., 0.1%) is typically sufficient. |

| Phosphoric Acid (H₃PO₄) | Mild oxidizer. Used in newer methods as an alternative to alkaline etching to minimize smut formation, followed by a detergent clean [31]. | Effective for high-particulate-cleanliness applications, as used for the National Ignition Facility [31]. |

| Citrinox | Citric acid-based cleaner. Effectively removes copper smut without the use of more hazardous acids [31]. | A safer, environmentally friendly alternative, suitable for alloys prone to smutting (e.g., 2219) [31]. |

| Almeco 18/29 | Commercial alkaline detergents. Used to remove oils and modify the oxide layer without aggressive etching [31]. | Often used in initial cleaning steps or for reforming the oxide layer on extruded aluminum [31]. |

Stainless Steel Pre-Treatment for UHV

Background and Principles

Ultra-high purity (UHP) 316L stainless steel is the material of choice for critical components in the semiconductor industry, such as electronic special gas (ESG) delivery pipelines [34]. While known for good corrosion resistance, its performance in UHV and corrosive ESG environments (involving HCl, HBr, HF, Cl₂) is critical. Trace moisture can condense and dissolve these gases, forming a highly aggressive acidic electrolyte that leads to corrosion. The resulting corrosion particles can detach and contaminate processing chambers, drastically reducing wafer yields [34]. Therefore, pre-treatment aims not only to clean but also to maximize the corrosion resistance of the passive film.

Advanced Passivation Protocol for UHP 316L Stainless Steel

The following protocol is based on recent research for a composite passivation strategy that combines Alternating Voltage Passivation (AVP) with Nitric Acid Passivation (NP) to achieve superior corrosion resistance without surface damage, making it ideal for semiconductor applications [34].

Figure 2: Stainless steel composite passivation workflow.

Step 1: Electropolishing (EP)

- Objective: Smooth the surface and create a baseline passive film with improved corrosion resistance.

- Procedure:

- Follow standard electropolishing procedures for 316L stainless steel. This typically involves immersing the part as an anode in a temperature-controlled acidic electrolyte (e.g., a mixture of sulfuric and phosphoric acids) and applying a specific current density.

- Rinse thoroughly with DI water after electropolishing. EP is recognized as an excellent technique for enhancing corrosion resistance and surface quality [34].

Step 2: Alternating Voltage Passivation (AVP)

- Objective: Dramatically enhance the thickness and stability of the passive film and selectively dissolve corrosive-inclusion weaknesses.

- Materials: Potentiostat, counter electrode, reference electrode, and electrolyte (e.g., 0.1 mol/L Na₂SO₄).

- Procedure:

Step 3: Nitric Acid Passivation (NP)

- Objective: Heal the micro-damage induced by AVP and further enrich the chromium content in the passive film, achieving a defect-free, highly protective surface.

- Procedure:

- Immerse the AVP-treated sample in a 20% nitric acid solution.

- Maintain the solution at 60°C for 60 minutes [34].

- This step eliminates surface micro-pitting and grain boundary etching caused by AVP.

Step 4: Rinse and Dry

- Objective: Remove all passivation chemicals.

- Procedure:

- Rinse the component thoroughly with DI water.

- Dry using filtered, oil-free air or nitrogen. The component now has a highly resistant, stable passive film suitable for UHV and corrosive ESG service.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Reagents & Materials for Stainless Steel Pre-Treatment

Table 3: Essential Reagents for Stainless Steel UHV Pre-Treatment

| Reagent/Solution | Function | Application Note |

|---|---|---|

| Electropolishing Electrolyte | Anodic dissolution. Levels micro-peaks, smooths the surface, and creates a uniform baseline passive film, improving corrosion resistance [34]. | Typically a mixture of sulfuric and phosphoric acids. Process parameters (temp, current density, time) are critical. |

| Sodium Sulfate (Na₂SO₄) Solution | Electrolyte for AVP. Provides the conductive medium for the alternating voltage treatment. | A 0.1 mol/L concentration is used as a non-aggressive medium to facilitate passive film growth [34]. |

| Nitric Acid (HNO₃) | Traditional passivating agent. Promotes the formation of a chromium-rich passive oxide layer by selectively dissolving iron from the surface. | Used at 20% concentration and elevated temperature (60°C) to heal AVP-induced surface damage and enhance film stability [34]. |

| Ultra-High Purity 316L Stainless Steel | Base material. Specially manufactured with strict limits on S, Mn, Al, C, and Ca to minimize the formation of corrosive inclusions [34]. | Complies with SEMI F20 standard. The reduced inclusion count is a prerequisite for the success of advanced passivation techniques. |

The pursuit of UHV conditions demands rigorous and repeatable metal pre-treatment protocols. For aluminum, this involves a two-stage process of alkaline etching to strip the porous native oxide, followed by acid de-smutting to remove residual metallic impurities, resulting in a clean, thin, and protective new oxide layer. For ultra-high purity stainless steel in the most demanding semiconductor applications, a composite passivation strategy combining the film-forming power of AVP with the surface-healing properties of nitric acid passivation offers a breakthrough in corrosion resistance without compromising surface quality. By adhering to these detailed application notes and protocols, researchers and engineers can reliably prepare metal surfaces that meet the extreme cleanliness and stability standards required for advanced UHV systems.

Plasma cleaning, utilizing the fourth state of matter, is a critical surface preparation technique in ultra-high vacuum (UHV) environments for research and industrial applications. This process employs an ionized gas containing reactive species to remove contaminants at the molecular level, achieving cleanliness standards unattainable through conventional methods [35]. Within the context of UHV surface preparation protocol research, the selection of specific plasma chemistry—hydrogen, oxygen, or argon—determines the mechanism and outcome of the cleaning process [35] [36]. This analysis provides a comparative examination of these three plasma techniques, detailing their fundamental mechanisms, specific applications across material classes, and standardized protocols for reproducible surface preparation in UHV systems.

Comparative Analysis of Plasma Types

The efficacy of plasma cleaning depends on selecting the appropriate process gas, which determines the dominant cleaning mechanism—chemical reaction, physical sputtering, or a combination of both. The table below summarizes the key characteristics of hydrogen, oxygen, and argon plasmas.

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of Hydrogen, Oxygen, and Argon Plasma Cleaning Techniques

| Parameter | Hydrogen Plasma | Oxygen Plasma | Argon Plasma |

|---|---|---|---|

| Primary Mechanism | Chemical reduction [35] [36] | Chemical oxidation [35] [37] | Physical sputtering [35] [38] |

| Chemical Reactivity | Highly reductive [35] | Highly oxidative [35] [37] | Inert (non-reactive) [37] |

| Key Reactive Species | H atoms, H⁺ ions, H₂⁺ ions [36] | O atoms, O₂⁺, O₂⁻, O₃ [37] [36] | Ar⁺ ions, metastable Ar atoms [37] |

| Primary Contaminant Removal | Native oxide layers [35] [36] | Organic residues (hydrocarbons) [35] [37] | Inorganics, salts, ceramics [36] |

| By-products | H₂O vapor [36] [38] | CO, CO₂, H₂O [35] [36] | Vaporized contaminants [35] |

| Effect on Surface Chemistry | Reduces metal oxides to pure metal; leaves H-terminated surfaces [35] [39] | Adds oxygen-containing polar groups (e.g., -OH, C=O); creates hydrophilic surface [37] | Creates surface radicals; post-air exposure introduces functional groups [37] |

| Effect on Surface Morphology | Minimal roughening [38] | Can slightly roughen polymers [37] | Can increase roughness via micro-sandblasting [36] [38] |

| Ideal Material Substrates | Metals (e.g., Silver, Copper) [35] | Polymers, glasses, metals needing activation [35] [37] | Inert materials, ceramics, heat-sensitive metals [36] [38] |

| UHV Applications | Preparing oxide-free surfaces for epitaxy, electrical contacts, and soldering [35] [39] | Creating pristine, high-energy surfaces for bonding and coating; bio-device preparation [35] [38] | Atomically clean surfaces for adhesion promotion; pre-sputtering/pre-deposition cleaning [36] |

Detailed Plasma Mechanisms and Applications

Oxygen Plasma: Oxidative Cleaning