XPS Surface Analysis: A Comprehensive Guide for Biomedical Researchers and Drug Development

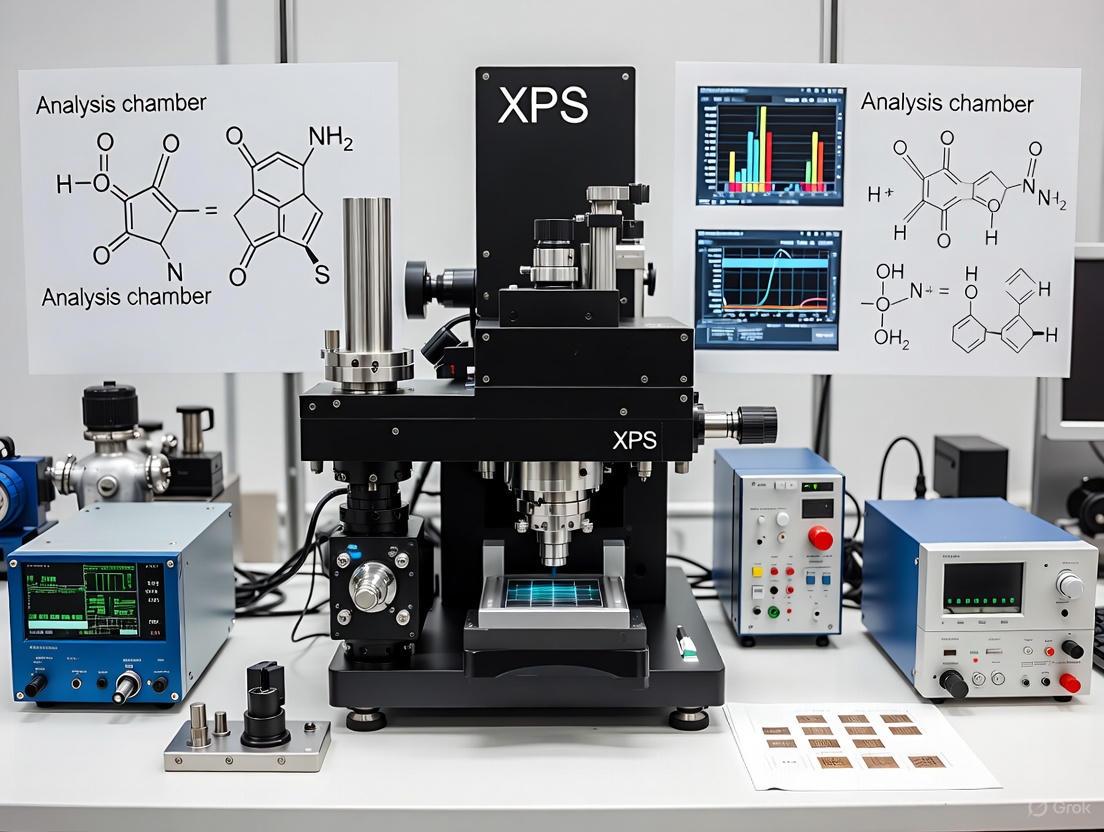

This guide provides a thorough exploration of X-ray Photoelectron Spectroscopy (XPS), a powerful surface-sensitive technique crucial for analyzing material composition and chemical states at the nanoscale.

XPS Surface Analysis: A Comprehensive Guide for Biomedical Researchers and Drug Development

Abstract

This guide provides a thorough exploration of X-ray Photoelectron Spectroscopy (XPS), a powerful surface-sensitive technique crucial for analyzing material composition and chemical states at the nanoscale. Tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, it covers foundational principles, practical methodologies, common challenges, and comparative analysis with other techniques. The content addresses key intents from understanding core concepts to applying XPS for quality assurance in medical devices, troubleshooting analytical issues, and validating its use in biomedical and clinical research contexts to advance material biocompatibility and drug delivery systems.

What is XPS? Understanding the Core Principles and Capabilities

X-Ray Photoelectron Spectroscopy (XPS), also known as Electron Spectroscopy for Chemical Analysis (ESCA), has become the most widely used method of surface analysis over the past three decades [1]. This analytical technique is essential for research spanning from traditional chemistry and materials science into environmental, atmospheric, and biological systems [1]. The fundamental principle underlying XPS is the photoelectric effect, which enables the identification of all elements except hydrogen and helium on sample surfaces by measuring the binding energies of emitted photoelectrons during X-ray excitation [1]. This article explores the core physics of this phenomenon and its application in modern surface science, providing researchers with detailed protocols for effective implementation.

Fundamental Physical Principles of the Photoelectric Effect

The Photoelectric Process

The photoelectric effect, for which Albert Einstein received the Nobel Prize in 1921, describes the emission of electrons from a material when it is exposed to electromagnetic radiation of sufficient energy. In XPS, this phenomenon occurs through a precise sequence of physical interactions:

- Photon Absorption: An incident X-ray photon with energy hν is absorbed by an electron in an inner atomic orbital.

- Electron Emission: If the photon energy exceeds the electron's binding energy, the electron is ejected from the atom with a specific kinetic energy.

- Energy Conservation: The process follows the conservation of energy principle: KE = hν - BE - φ, where KE is the measured kinetic energy of the photoelectron, hν is the incident X-ray energy, BE is the electron binding energy, and φ is the spectrometer work function.

This fundamental process enables XPS to provide both elemental identification and chemical state information through precise measurement of electron binding energies.

Diagram: The Photoelectric Effect in XPS

Figure 1. Fundamental process of photoelectron emission in XPS. The diagram illustrates the sequence from photon absorption to photoelectron emission and energy measurement, which forms the basis of XPS analysis.

Experimental Protocols for XPS Analysis

Pre-Analysis Planning and Assessment

Proper planning is crucial for obtaining reliable XPS data. The following checklist outlines critical considerations before conducting experiments:

- Define Analytical Question: Clearly articulate what information is needed from the analysis [1].

- Sample Compatibility: Verify that the sample size, form, and composition are compatible with XPS instrumentation and ultra-high vacuum requirements [1].

- Sensitivity Assessment: Determine if XPS has the required detection sensitivity for target elements and potential peak interferences [1].

- Depth Resolution Needs: Evaluate whether angle-resolved measurements, ion sputtering, or specialized XPS configurations are needed for depth profiling [1].

- Sample Preparation: Plan appropriate handling and cleaning procedures to minimize contamination layers [1].

Step-by-Step Measurement Protocol

Instrument Calibration

- Verify instrument performance using standard samples

- Confirm energy scale calibration with known reference materials

- Document all instrument parameters including X-ray source settings and analyzer configurations [1]

Sample Loading and Preparation

- Mount sample securely using appropriate holders

- Implement charge control strategies for insulating specimens

- Minimize atmospheric exposure time before introducing to analysis chamber

Data Collection Strategy

- Acquire survey spectra (0-1100 eV binding energy) for elemental identification [1]

- Collect high-energy-resolution regional spectra for elements of interest

- Use appropriate dwell times and scan repetitions for adequate statistics [1]

- Monitor for potential X-ray induced specimen damage throughout analysis [1]

Depth Profiling (When Required)

Data Interpretation and Analysis Protocol

Energy Alignment and Charge Referencing

- Apply charge correction using adventitious carbon (C 1s at 284.8 eV) or known reference peaks

- Verify correction consistency across all spectral regions

Peak Identification and Fitting

- Identify all major photoelectron peaks using established binding energy databases [3]

- Employ appropriate background subtraction methods (Shirley, Tougaard, or linear)

- Use physically meaningful constraints during fitting procedures

- Document all fitting parameters including peak positions, full width at half maximum (FWHM), and area ratios

Quantitative Analysis

- Calculate elemental concentrations using relative sensitivity factors

- Account for matrix effects and inelastic mean free paths in quantification

- Report uncertainties and detection limits based on signal-to-noise ratios

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 1: Essential materials and reagents for XPS analysis

| Item | Function/Purpose | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Standard Reference Materials | Energy scale calibration and quantitative verification | Au, Ag, Cu foils for regular instrument calibration [1] |

| Conductive Adhesive Tapes | Sample mounting for analysis | Double-sided carbon or copper tapes for electrical contact |

| Charge Neutralization Systems | Surface potential stabilization | Low-energy electron flood guns for insulating samples [1] |

| Ion Sputtering Sources | Depth profiling and surface cleaning | Monoatomic (Ar+) for metals; cluster sources for organics [2] |

| XPS Knowledge Bases | Peak identification and chemical state analysis | Database resources for binding energies and chemical shifts [4] [3] |

| Ultra-High Vacuum Compatible Materials | Sample preparation and handling | Materials with low vapor pressure to maintain analysis chamber pressure |

Data Presentation and Analysis Parameters

Key Quantitative Parameters in XPS Analysis

Table 2: Critical parameters for XPS data acquisition and interpretation

| Parameter | Typical Values/Ranges | Significance |

|---|---|---|

| X-ray Source Energy | 1486.6 eV (Al Kα), 1253.6 eV (Mg Kα) | Determines ionization cross-sections and probing depth |

| Analysis Depth | 3-10 nm (depending on material) | Information depth for surface-sensitive measurements |

| Energy Resolution | 0.3-1.0 eV (routine), <0.3 eV (high-res) | Affects chemical state differentiation capability |

| Binding Energy Range | 0-1400 eV (covers all elements except H, He) | Comprehensive elemental coverage [1] |

| Detection Limits | 0.1-1.0 atomic percent | Element-dependent sensitivity factors |

| Depth Profiling Resolution | 1-10 nm (varies with sputter conditions) | Interface resolution in multilayer structures [2] |

Advanced Methodologies and Applications

Depth Profiling Techniques and Considerations

XPS depth profiling, particularly using ion sputtering methods, requires careful optimization to minimize artifacts and obtain accurate compositional information [2]. The workflow below outlines the decision process for selecting appropriate depth profiling methods:

Figure 2. Decision workflow for XPS depth profiling methodology. The selection between monoatomic and cluster ion sputtering depends on material type to minimize measurement artifacts [2].

Addressing Reproducibility Challenges

The widespread use of XPS has revealed significant reproducibility challenges in the scientific literature [1]. Implementation of standardized protocols is essential for generating reliable data:

- Instrument Performance Verification: Regular calibration using certified reference materials

- Documentation Standards: Comprehensive reporting of all experimental parameters [1]

- Data Analysis Consistency: Application of validated peak fitting procedures and constraints

- Interlaboratory Comparisons: Participation in proficiency testing programs when available

XPS remains an indispensable surface analysis technique rooted in the fundamental physics of the photoelectric effect. Its ability to provide both elemental identification and chemical state information with high surface sensitivity makes it uniquely valuable across numerous scientific disciplines. However, the technique's perceived simplicity often belies the careful experimental planning and execution required to generate reliable, reproducible data. By adhering to the detailed protocols and methodologies outlined in this article, researchers can leverage the full analytical power of XPS while avoiding common pitfalls associated with its implementation. As XPS continues to evolve with new source technologies, detection methods, and data analysis approaches, maintaining rigorous standards in its application will ensure its continued contribution to scientific advancement.

X-ray Photoelectron Spectroscopy (XPS), also known as Electron Spectroscopy for Chemical Analysis (ESCA), is a powerful surface-sensitive analytical technique that has become indispensable in modern materials research and development. This non-destructive method provides quantitative information about the elemental composition, chemical state, and electronic structure of the outermost layers of a material, typically the top 1-10 nm [5] [6]. The fundamental principle of XPS is based on the photoelectric effect, where X-rays irradiate a sample, causing the ejection of photoelectrons from core levels. By measuring the kinetic energy of these ejected electrons, the binding energy can be determined using the equation: Ebinding = Ephoton - (Ekinetic + φ), where Ephoton is the known X-ray energy, Ekinetic is the measured electron kinetic energy, and φ is the spectrometer work function [5] [6]. This relationship forms the basis for all XPS analysis, allowing researchers to identify elements present on material surfaces and their chemical environments with high precision.

The surface sensitivity of XPS arises from the short inelastic mean free path of electrons in solids, which limits the escape depth of photoelectrons to approximately the top 5-10 nm (about 30 atomic layers) of the material surface [5] [7]. This makes XPS particularly valuable for investigating surface-mediated processes such as catalysis, corrosion, adhesion, and various interfacial phenomena that dominate material behavior in practical applications. Since its development into a practical analytical tool by Dr. Kai Siegbahn and his colleagues (earning him the Nobel Prize in Physics in 1981), XPS has evolved to become a standard technique in surface science laboratories worldwide [5] [6].

Fundamental Principles and Technical Specifications

Core Physical Principles

XPS operates based on the photoelectric effect, where photons of sufficient energy eject electrons from core atomic orbitals. When an X-ray photon with energy ℎν strikes an atom, it may transfer its energy to a core-level electron, ejecting it with a kinetic energy given by: Ekinetic = ℎν - Ebinding - φ, where Ebinding is the electron's binding energy relative to the Fermi level, and φ is the spectrometer work function [5]. The measured kinetic energy of the photoelectrons is characteristic of specific elements, while subtle shifts in binding energy (known as chemical shifts) provide information about the chemical state and bonding environment of the emitting atoms [5] [6]. These chemical shifts occur because changes in the chemical environment affect the electrostatic screening of core electrons by valence electrons; for example, increased oxidation state typically results in higher binding energies due to reduced valence electron density [5].

For electrons in p, d, or f orbitals, spin-orbit splitting occurs, resulting in doublet peaks (e.g., p₁/₂ and p₃/₂) with characteristic intensity ratios and energy separations that aid in elemental identification [5]. The technique also produces Auger electron peaks, which result from the relaxation process following photoemission, and these can provide additional chemical information through the Auger parameter [5] [8]. The information depth in XPS is governed by the Beer-Lambert law: Is = I₀e^(-d/λ), where Is is the intensity of photoelectrons emitted at depth d below the surface, I₀ is the initial intensity, and λ is the inelastic mean free path of the electron in the material (typically 1-3.5 nm for Al Kα X-rays) [5]. This relationship means that approximately 95% of the detected signal originates from within 3λ of the surface, establishing the fundamental surface sensitivity of the technique.

Technical Specifications and Capabilities

Table 1: Key Technical Specifications of XPS Analysis

| Parameter | Specification | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Elements Detected | Lithium (Li) to Uranium (U) | Hydrogen and Helium not detectable [6] [9] |

| Detection Limits | 0.01-1 atomic % (100-1000 ppm) | Dependent on element and matrix [6] [9] |

| Surface Sensitivity | 1-10 nm (top 5-10 nm typical) | ~30 atomic layers [5] [7] [9] |

| Lateral Resolution | 10 μm to 200 μm | Down to 200 nm with synchrotron sources [6] |

| Quantitative Accuracy | ±10% for major elements | ±60-80% for weak signals (10-20% of strongest peak) [6] |

| Analysis Depth | ~3-10 nm | Approximately 3 times the inelastic mean free path (λ) [5] |

| Chemical Shift Resolution | ±0.1 eV | Typically sufficient to distinguish oxidation states [5] |

XPS provides exceptional capabilities for surface chemical analysis with particular strengths in several areas. The technique is semi-quantitative without requiring standards, using relative sensitivity factors (RSFs) to convert peak areas to atomic concentrations according to the formula: Cₓ = (Iₓ/Sₓ)/(ΣIᵢ/Sᵢ), where Cₓ is the concentration of element x, Iₓ is the measured intensity, Sₓ is the elemental sensitivity factor, and ΣIᵢ/Sᵢ is the sum of these ratios for all detected elements [5]. This quantitative capability extends to both conducting and insulating materials, with the latter requiring charge neutralization systems such as electron flood guns to compensate for surface charging effects [5] [8]. The exceptional surface sensitivity of XPS means it often reveals composition differences between the surface and bulk material that would be missed by techniques with greater sampling depths, such as energy dispersive spectrometry (EDS) with excitation volumes extending up to 3 microns into the material [5].

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Sample Preparation and Handling Protocols

Proper sample preparation is critical for obtaining reliable XPS data. Samples must be compatible with ultra-high vacuum (UHV) conditions (<10⁻⁹ Torr), as the emitted photoelectrons have relatively low energy and are readily absorbed by ambient atmosphere [5] [6]. Solid samples should be cut to appropriate dimensions for the sample holder (typically 1-2 cm in maximum dimension), with powders mounted using double-sided conductive tape or pressed into indium foil to minimize charging [5]. For highly volatile materials, freezing protocols may be employed, where hydrated samples are frozen in their hydrated state in an ultrapure environment and allowed to sublime multilayers of ice prior to analysis [6].

Surface contamination represents a significant challenge in XPS analysis, as the technique is exquisitely sensitive to the outermost molecular layers. Adventitious carbon from atmospheric exposure is ubiquitous and is often used as a charge reference by setting the C 1s peak to 284.8 eV [5] [8]. To minimize contamination, samples should be handled with clean gloves, using tweezers, and stored in clean, dry environments prior to analysis. For surface-sensitive studies, additional cleaning procedures such as solvent cleaning, argon ion sputtering to "dust off" environmental contaminants, or in situ treatments (heating, fracturing, or scraping) may be employed to reveal the intrinsic surface chemistry [5] [7].

Data Acquisition Protocols

XPS data collection follows a systematic approach to ensure comprehensive surface characterization:

Survey Scans: Wide energy range scans (typically 0-1100 eV or 0-1400 eV) performed initially to identify all elements present on the surface. Acquisition parameters: Pass energy of 100-200 eV, step size of 1.0 eV, and dwell times of 50-100 ms per step to ensure adequate signal-to-noise ratio while maintaining reasonable acquisition times (typically 1-20 minutes) [5] [6].

High-Resolution Regional Scans: Narrow energy range scans centered on photoelectron peaks of interest, performed to determine chemical states and obtain quantitative data. Acquisition parameters: Pass energy of 20-50 eV, step size of 0.05-0.1 eV, and longer dwell times (100-500 ms) to achieve high energy resolution [5] [6]. Multiple sweeps are often required to achieve sufficient signal-to-noise ratio for accurate peak fitting.

Charge Compensation: For insulating samples, the electron flood gun should be optimized to provide sufficient low-energy electrons to neutralize surface charge without degrading spectral resolution. The optimal settings vary by instrument and sample, requiring empirical determination [5] [8].

Data Collection Order: Always collect survey spectra first, followed by high-resolution regions, as prolonged X-ray exposure may degrade certain materials, particularly organics, polymers, and some highly oxygenated compounds [6].

XPS Experimental Workflow: This diagram illustrates the standard protocol for XPS analysis, from sample preparation through data acquisition and analysis.

Depth Profiling Methodology

Depth profiling enables the investigation of compositional changes as a function of depth below the original surface. The most common approach combines alternating cycles of ion sputtering and XPS analysis:

Sputter Source Setup: Typically use argon ion gun with acceleration voltages of 1-5 kV for adequate sputter rates without excessive atomic mixing or sample damage. Lower energies (0.5-1 kV) are preferred for organic materials and delicate structures [5].

Sputter Rate Calibration: Calibrate using standards of known thickness (e.g., thermal oxide on silicon wafer). Report sputter rates in nm/minute based on this calibration [5].

Analysis Sequence: Program automated sequences of brief sputtering (5-30 seconds) followed by XPS analysis of selected regions (multiplex routine). The cycle repeats until the desired depth is profiled [5].

Cluster Ion Sources: For organic materials and delicate structures, gas cluster ion beams (GCIB) provide more gentle sputtering with reduced chemical damage and better preservation of chemical state information [9].

Data Presentation: Depth profiles typically display atomic concentration (normalized to 100%) as a function of sputter time or depth, revealing layer structures, interfacial reactions, and diffusion profiles [5].

Data Analysis and Interpretation

Quantitative Analysis Procedures

Quantitative analysis in XPS involves measuring peak areas and correcting them with relative sensitivity factors (RSFs) that account for elemental differences in photoionization cross-sections, analyzer transmission functions, and electron mean free paths. The standard quantification formula is:

Cₓ = (Iₓ/Sₓ) / Σ(Iᵢ/Sᵢ)

Where Cₓ is the atomic concentration of element x, Iₓ is the background-subtracted peak area, Sₓ is the relative sensitivity factor, and the denominator represents the sum of this ratio for all elements detected [5]. The accuracy of quantitative XPS analysis depends on several factors, including sample homogeneity, surface roughness, peak overlap, and the accuracy of the sensitivity factors used. For major constituents (peak intensities >10% of the strongest signal), quantitative accuracy of 90-95% can be expected, while weaker signals may have accuracies of 60-80% of the true value [6].

Peak fitting of high-resolution spectra is essential for extracting chemical state information. This process involves:

Background Subtraction: Typically using Shirley or Tougaard backgrounds to account for inelastically scattered electrons [5] [8].

Peak Model Selection: Using appropriate combinations of Gaussian-Lorentzian functions (typically 70-90% Gaussian) to represent individual chemical states [8].

Constraint Application: Applying physically meaningful constraints based on known spin-orbit splitting (energy separation and area ratios for doublets) and FWHM relationships [5] [8].

Validation: Ensuring the fitted components correspond to realistic chemical states by comparison to reference spectra from databases such as the NIST XPS Database or PHI Handbook of X-ray Photoelectron Spectroscopy [5] [8].

Chemical State Identification

Chemical state identification relies on the precise measurement of binding energy shifts that occur when elements enter different bonding environments. These chemical shifts typically range from 0.1 eV to several eV, significantly larger than the instrumental resolution of modern XPS instruments (±0.1 eV) [5]. General trends in chemical shifts include:

Higher Oxidation States: Typically exhibit higher binding energies due to the reduced electron density around the atom (e.g., Ti⁰ vs. Ti⁴⁺ has a ~5 eV shift) [5].

Electronegative Ligands: Bonding to more electronegative elements increases binding energy (e.g., fluorocarbons vs. hydrocarbons) [5].

Metallic vs. Oxide States: Pure metallic states typically have 0.5-3 eV lower binding energies than their oxidized counterparts [5].

For complex materials with multiple bonding environments, such as polymers or mixed oxidation state compounds, high-resolution spectra must be deconvoluted into individual components representing distinct chemical environments [5] [7]. The Auger parameter, which combines XPS and AES measurements, provides additional chemical state information that is independent of charge referencing and particularly valuable for certain elements [8].

Table 2: Representative Chemical Shift Ranges for Common Elements

| Element | Core Level | Chemical State | Binding Energy Range (eV) | Characteristic Features |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Carbon | C 1s | C-C/C-H | 284.8 (reference) | Adventitious carbon reference [5] [8] |

| C-O | 286.0-286.5 | ~1.5 eV shift from C-C [5] | ||

| C=O | 287.5-288.0 | ~3 eV shift from C-C [5] | ||

| O-C=O | 288.5-289.0 | ~4 eV shift from C-C [5] | ||

| Oxygen | O 1s | Metal oxides | 529-531 | Lattice oxygen [5] |

| Hydroxides | 531.0-532.5 | ~1-2 eV higher than oxides [5] | ||

| Adsorbed H₂O | 532.5-533.5 | ~3-4 eV higher than oxides [5] | ||

| Nitrogen | N 1s | Organic/amine | 399.0-400.0 | Neutral nitrogen [5] |

| Protonated amine | 401.0-402.0 | ~2 eV shift from neutral [5] | ||

| Nitro/o | 405.0-406.0 | ~6 eV shift from neutral [5] | ||

| Silicon | Si 2p | Elemental Si | 99.0-99.5 | Metallic silicon [7] |

| SiO₂ | 103.0-104.0 | ~4 eV shift from elemental [7] |

Applications in Research and Industry

Pharmaceutical and Biomedical Applications

XPS plays a critical role in pharmaceutical development and biomedical research, particularly in characterizing surface properties that govern biological interactions. Key applications include:

Drug Delivery Systems: Surface characterization of polymeric nanoparticles, liposomes, and other drug carriers to verify surface functionalization, quantify targeting ligand density, and assess surface charge [10]. These parameters significantly influence biodistribution, cellular uptake, and therapeutic efficacy.

Medical Implants: Analysis of surface composition and chemical states of implant materials (e.g., titanium, stainless steel, polymers) to verify surface treatments, monitor oxide layer composition and thickness, and detect contaminants that may affect biocompatibility [10] [9].

Surface Modification Verification: Confirming the success of surface treatments such as plasma modification, silanization, and PEGylation intended to enhance biocompatibility, reduce fouling, or enable specific biointeractions [10] [7].

Contaminant Identification: Detection and quantification of surface contaminants that may affect drug product stability, sterility, or performance, including silicone oils, mold release agents, and processing residues [7] [9].

Materials Science and Engineering Applications

XPS provides essential insights for advanced materials development across multiple industries:

Semiconductor Technology: Characterization of ultra-thin films, high-k dielectrics, interface reactions, and contamination control in device fabrication [10] [11]. XPS can measure oxide thickness, interface quality, and dopant distribution in emerging semiconductor materials for electronics and photovoltaics [11].

Catalyst Research: Analysis of oxidation states and surface composition of heterogeneous catalysts, correlation of surface chemistry with catalytic activity, and studies of catalyst deactivation mechanisms [5] [10].

Corrosion Science: Investigation of passive film composition, thickness, and chemistry on metals and alloys, studies of corrosion initiation, and evaluation of corrosion protection treatments [5] [9].

Polymer Surface Modification: Verification of surface treatments (plasma, flame, chemical) for improving adhesion, printability, or biocompatibility; analysis of polymer degradation and weathering [5] [7].

Adhesion Science: Identification of failure mechanisms in adhesive bonds, characterization of surface treatments for improved adhesion, and analysis of interphase chemistry in composite materials [7].

Emerging and Niche Applications

The application space for XPS continues to expand with technological advancements:

Environmental Science: Study of mineral-fluid interfaces, contaminant sorption, and nanoparticle environmental behavior using ambient pressure XPS (AP-XPS) that allows analysis under more realistic environmental conditions [6].

Energy Storage and Conversion: Characterization of electrode surfaces, solid-electrolyte interphase (SEI) layers in batteries, catalyst surfaces in fuel cells, and light-absorbing materials in photovoltaics [10] [11].

Two-Dimensional Materials: Surface analysis of graphene, transition metal dichalcogenides, and other 2D materials, including characterization of functionalization, doping, and interface properties [8].

Heritage Conservation: Analysis of historical artifacts and artworks to identify surface degradation products, original manufacturing techniques, and inform conservation strategies [6].

Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for XPS Analysis

| Reagent/Material | Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Conductive Tapes | Sample mounting for powders and irregular shapes | Double-sided carbon tape preferred; may contribute to C 1s signal [5] |

| Indium Foil | Substrate for powder mounting | Malleable metal with well-characterized XPS signals [5] |

| Reference Materials | Energy scale calibration | Gold, copper, and silver foils for Fermi edge and peak position references [8] |

| Argon Gas | Ion sputtering for depth profiling and cleaning | High purity (99.999%) required to minimize contamination [5] |

| Charge Reference Standards | Binding energy calibration | Adventitious carbon (C 1s at 284.8 eV) or deposited gold nanoparticles [5] [8] |

| Silicon Wafers | Reference substrates and thickness standards | Native oxide provides SiO₂ reference; used for sputter rate calibration [5] |

| Certified Standard Materials | Quantitative accuracy verification | NIST-traceable standards with certified surface composition [6] |

Advanced Techniques and Methodologies

Angle-Resolved XPS (ARXPS)

Angle-Resolved XPS enables non-destructive depth profiling with nanometer-scale resolution by varying the emission angle between the sample surface and the analyzer. At grazing angles (relative to the surface), the analysis becomes more surface-sensitive, enhancing the signal from the outermost layers. The technique is particularly valuable for:

Thin Film Characterization: Determining layer thicknesses in the 1-10 nm range without sputtering [8].

Interface Analysis: Probing buried interfaces by enhancing signals from interfacial species [8].

Molecular Orientation Studies: Detecting anisotropic distribution of functional groups at surfaces [8].

The information depth in ARXPS follows the relationship: d(θ) = 3λ sin(θ), where θ is the emission angle measured from the surface plane, and λ is the electron inelastic mean free path. This allows controlled variation of the sampling depth from approximately 0.5-10 nm [5] [8].

Imaging XPS and Mapping

XPS imaging capabilities enable the creation of chemical state maps with micrometre-scale lateral resolution. Two primary approaches are employed:

Microprobe Mode: A focused X-ray spot is rastered across the sample surface while the spectrometer collects electrons from each position. This approach provides high spatial resolution (down to 3 µm with laboratory sources, 200 nm with synchrotron sources) but requires longer acquisition times [6] [9].

Parallel Imaging Mode: The sample is illuminated with a broad X-ray beam, and a position-sensitive detector simultaneously collects electrons from different regions of the sample. This approach is faster but typically offers lower spatial resolution (10-30 µm) [6].

XPS imaging applications include contamination mapping, analysis of patterned surfaces, heterogeneous catalyst characterization, and failure analysis of electronic devices [6] [9].

XPS Instrumentation Schematic: This diagram shows the key components of an XPS instrument and their relationships in the measurement process.

Comparison with Complementary Techniques

Understanding the position of XPS within the broader analytical landscape is essential for appropriate technique selection. Compared to other surface analysis methods:

XPS vs. AES (Auger Electron Spectroscopy): XPS provides better chemical state information and handles insulating samples more easily, while AES offers superior spatial resolution (down to 10 nm) and is more sensitive to light elements [5] [8].

XPS vs. SIMS (Secondary Ion Mass Spectrometry): XPS provides quantitative elemental and chemical state information from the top 1-10 nm, while SIMS offers superior detection limits (ppm-ppb) and isotopic sensitivity but is less quantitative and more destructive [7].

XPS vs. FTIR (Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy): XPS probes the top few nanometers with elemental specificity, while FTIR provides molecular functional group information with greater sampling depths (micrometers) [7].

XPS vs. UPS (Ultraviolet Photoelectron Spectroscopy): XPS measures core-level electrons for elemental and chemical state analysis, while UPS probes valence electrons for electronic structure and work function measurements with even greater surface sensitivity (2-3 nm) [12].

The combination of XPS with complementary techniques often provides the most comprehensive understanding of material surfaces, leveraging the specific strengths of each method while compensating for their respective limitations.

X-ray Photoelectron Spectroscopy (XPS) has become an indispensable surface analysis technique across diverse fields, including materials science, semiconductor development, and pharmaceutical research, due to its unique capability to provide quantitative elemental composition and chemical state information from the outermost atomic layers of a material [10] [13]. Despite its widespread adoption and utility, the technique possesses several intrinsic limitations that can significantly impact the quality of analytical data, the scope of analyzable samples, and the overall efficiency of research and development workflows. This application note provides a detailed examination of three critical limitations—ultra-high vacuum (UHV) requirements, sample size constraints, and charging effects—within the context of advanced material and drug development research. It further offers validated experimental protocols and mitigation strategies to assist researchers in optimizing their XPS analyses, ensuring data reliability, and expanding the technique's applicability to challenging sample types.

Ultra-High Vacuum (UHV) Requirements

The Imperative for UHV Conditions

The operational requirement for Ultra-High Vacuum (UHV), typically defined as pressures lower than 1×10⁻⁹ torr, is fundamental to the XPS technique [14]. This environment is necessary to ensure that photoelectrons ejected from the sample surface can travel along their mean free path to the detector without undergoing scattering events with gas molecules. In UHV, the mean free path of a gas molecule exceeds approximately 40 km, thereby preserving the energy and intensity of the photoelectron signal and enabling accurate compositional analysis [14]. Furthermore, UHV is essential for maintaining a pristine, contamination-free sample surface for the duration of the analysis by minimizing the adsorption of ambient gas molecules onto the area of interest.

Practical Constraints and Sample Compatibility

The UHV requirement imposes significant practical constraints on the types of samples suitable for XPS analysis and the procedures for their handling. The fundamental challenge is that many materials are unstable or volatile under such low-pressure conditions [15]. This is particularly problematic for biological specimens, certain hydrated polymers, pharmaceutical compounds with high vapor pressures, and any materials containing volatile solvents or plasticizers. When placed in the UHV chamber, these samples can outgas, decompose, or undergo irreversible morphological changes, leading to erroneous analytical results and potential contamination of the spectrometer.

Table 1: UHV System Components, Their Functions, and Associated Challenges

| System Component | Primary Function | Operational Challenge |

|---|---|---|

| Roughing Pump | Initial pump-down from atmospheric pressure | Removes bulk gas; insufficient for UHV |

| High-Vacuum Pump | Achieves high vacuum (e.g., Turbomolecular Pump) | Requires clean, oil-free operation to prevent contamination |

| UHV Pump | Maintains sustained UHV (e.g., Ion Pump, NEG Pump) | Limited pumping capacity for high outgassing samples |

| Bake-Out System | Heats chamber walls to desorb water vapor | Time-consuming (hours to days); can damage sensitive samples |

| Airlock System | Introduces samples without breaking main UHV | Adds complexity but drastically improves throughput |

Mitigation Strategies and Protocols

Protocol 2.3.1: Sample Pre-Screening for UHV Compatibility

- Stability Assessment: Prior to analysis, investigate the thermal stability and vapor pressure of the sample material. Thermogravimetric Analysis (TGA) is a recommended pre-screening method.

- Visual Inspection: For liquid or semi-solid samples, a test vial can be placed in a low-pressure desiccator to observe for boiling, bubbling, or phase separation.

- Alternative Preparation: If UHV compatibility is questionable, consider cryogenic cooling of the sample stage to reduce vapor pressure, or explore alternative sample preparation such as thorough drying or embedding in a stable matrix, acknowledging potential for surface modification.

- Utilize Load-Lock System: Transfer the sample into the analytical chamber using a dedicated load-lock, which is pumped separately to minimize exposure of the main chamber to atmosphere.

- Pre-Pumping: Pump the load-lock to a medium-high vacuum (e.g., 10⁻⁶ torr) for a predetermined period to allow for initial outgassing.

- Monitor Pressure: Closely monitor the pressure in the main analytical chamber during and after sample transfer. A significant, sustained pressure rise indicates high sample outgassing, necessitating pump-down time or removal of the sample.

Diagram 1: UHV Sample Introduction Workflow. This protocol ensures the main chamber remains under UHV.

Sample Size and Geometry Constraints

The Nature of the Constraint

A frequently encountered practical limitation in XPS analysis stems from the physical dimensions and topography of the sample. Unlike electron beams used in techniques like SEM, X-ray beams cannot be focused as finely [15]. Consequently, the analyzed area is typically large, ranging from tens of microns to several millimeters, and the signal obtained is an average over this entire area [15]. This characteristic poses two major challenges: First, samples must be small enough to fit inside the UHV chamber's specimen stage, which often has limited clearance. Second, and more critically, the surface of the sample must be flat and smooth within the plane of analysis. Rough or highly textured surfaces can cause differential charging (discussed in Section 4) and distort quantitative analysis because photoelectrons emitted from sloped surfaces or crevices may not reach the detector, leading to unrepresentative sampling.

Impact on Analysis

This averaging effect over a relatively large area makes it difficult to analyze small, isolated features or heterogeneous materials with micron-scale domain sizes. If a sample is too small, or incorrectly positioned, it may not adequately cover the X-ray beam spot, leading to a weak signal and potential detection of the underlying sample holder, which contaminates the spectral data. The technique is, therefore, inherently not suited for analyzing the bulk composition of materials, as its information depth is limited to approximately ~10 nm [15].

Mitigation Strategies and Protocols

Protocol 3.3.1: Preparation of Small or Non-Ideal Samples

- Mounting Substrates: For powders or small particles, use a stable, non-contaminating substrate. Indium foil is excellent as it is malleable, conductive, and provides a clean background. Alternatively, use a pre-cleaned silicon wafer.

- Adhesive Selection: If necessary, use a double-sided conductive carbon tape to affix the sample. Avoid using non-conductive tapes or epoxies that can outgas.

- Flatness Assurance: Gently press the sample onto the substrate to ensure maximum contact and a flat upper surface. For powders, a small, clean glass slide can be used to press and spread the sample into a thin, uniform layer.

- Electrical Grounding: Verify that the mounting method provides an electrical path to the grounded sample holder, especially for insulating samples, to help mitigate charging.

Table 2: Research Reagent Solutions for Sample Preparation

| Material/Reagent | Primary Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Indium Foil | Conductive, malleable mounting substrate | Excellent for powders; provides a cold-weld seal; clean XPS spectral background. |

| Conductive Carbon Tape | Adhesive for mounting samples | Provides electrical contact to holder. Check for outgassing potential in UHV. |

| Pre-cleaned Silicon Wafer | Flat, low-background substrate | Ideal for depositing solutions, nanoparticles, or thin films. |

| Custom Sample Holder | Accommodate non-standard shapes | 3D-printed or machined holders can position wires, fragments, etc. |

Charging Effects

Fundamentals of Surface Charging

Charging is arguably the most pervasive analytical challenge in XPS, particularly when analyzing insulating materials. The process involves a steady flux of positively charged X-rays onto the sample, which causes the emission of negatively charged photoelectrons. If the sample is electrically insulating, this electron emission creates a positive charge buildup on the surface because the lost electrons cannot be replenished [16]. This positive charge affects the kinetic energy of subsequently emitted photoelectrons, resulting in a shift in the measured binding energy and often peak broadening or distortion [16] [17]. This effect compromises the accuracy of elemental identification and, most importantly, the determination of chemical states.

Types of Charging and Complexity

The problem is compounded by differential charging, where different regions of the sample surface acquire different charge potentials [17]. This can occur horizontally across a heterogeneous material or vertically in thin insulating films on conductive substrates [17]. The result is peak broadening, asymmetry, or even the appearance of multiple peaks for a single chemical species, making spectral interpretation extremely difficult. A common but often problematic practice is charge referencing the C 1s peak of adventitious carbon to 284.8 eV. Studies have shown this value can be inconsistent, varying significantly based on the substrate material and the nature of the carbon contamination [17].

Advanced Mitigation Strategies and Protocols

Recent research has demonstrated innovative approaches to charge neutralization. One promising method is UV-Assisted Charge Neutralization, where ultraviolet light is irradiated onto the sample surface during XPS analysis [16]. The UV light generates low-energy photoelectrons that adsorb onto the positively charged, X-ray-irradiated region, effectively suppressing charging intensity and enhancing its temporal stability and spatial uniformity [16]. This method has been shown to be at least as effective as, and sometimes superior to, traditional dual-beam (low-energy electrons and ions) flood guns, particularly in maintaining sample integrity.

Protocol 4.3.1: Implementing UV-Assisted Charge Neutralization

- Equipment Setup: Ensure the XPS instrument is equipped with a UV source (e.g., a deuterium lamp) that can be directed at the sample surface. The UV irradiation should be introduced concurrently with the X-ray beam.

- Optimize UV Intensity: Systematically adjust the intensity and focus of the UV light. The goal is to use the minimum flux required to stabilize the binding energy scale, as excessive UV flux could potentially induce sample damage.

- Monitor Spectral Stability: Acquire successive rapid scans of a core level peak (e.g., C 1s or a substrate peak). The neutralization is effective when the peak position remains stable between scans with minimal broadening.

- Validate with Reference Standard: Analyze a known insulating standard (e.g., a clean SiO₂ wafer) to calibrate and validate the effectiveness of the UV neutralization under your specific instrumental conditions.

Protocol 4.3.2: Strategy for Analyzing Thin Insulating Films on Conductive Substrates

- Assessment: Determine if the insulating layer is thin enough (typically <5 nm) that photoelectrons from the conductive substrate can be detected.

- Flood Gun Management: For such samples, it is often advisable to turn the standard electron flood gun OFF. Using the flood gun can induce vertical differential charging by creating a negative charge on the surface layer that is decoupled from the grounded substrate [17].

- Alternative Neutralization: If charging persists, use the UV-assisted neutralization protocol (Protocol 4.3.1) or operate the flood gun at the lowest possible electron flux and energy.

Diagram 2: Logical decision pathway for diagnosing and mitigating charging effects during XPS analysis.

The powerful surface sensitivity of XPS comes with the inherent challenges of UHV requirements, sample size constraints, and charging effects. These limitations, however, can be systematically managed through careful experimental planning and the application of robust protocols. As demonstrated, strategies such as load-lock sample introduction, appropriate substrate mounting, and advanced neutralization techniques like UV illumination are highly effective in expanding the range of analyzable samples and ensuring the generation of reliable, high-quality data. The ongoing integration of artificial intelligence for data interpretation and technological trends toward miniaturization and automation are poised to further mitigate these limitations, solidifying the role of XPS as a critical tool for surface analysis in scientific research and industrial development [10] [13].

X-ray Photoelectron Spectroscopy (XPS) is a surface-sensitive quantitative spectroscopic technique that measures the very topmost 50–60 atoms, 5–10 nm of any surface [6]. This technique belongs to the family of photoemission spectroscopies in which electron population spectra are obtained by irradiating a material with a beam of X-rays [6]. XPS is a powerful measurement technique because it not only identifies what elements are present in a material but also reveals what other elements they are bonded to, enabling researchers to determine chemical state information and empirical formulas [6]. The fundamental physical principle underlying XPS is the photoelectric effect, where electrons are ejected from a material when it is irradiated with X-rays of sufficient energy [18]. The kinetic energy of these ejected photoelectrons is measured by the spectrometer, and the binding energy of the electrons within their parent atoms is calculated using the photoelectric equation: Ebinding = Ephoton - (Ekinetic + ϕ), where Ephoton is the energy of the X-ray photons, Ekinetic is the kinetic energy of the ejected electron measured by the instrument, and ϕ is the work function of the spectrometer [6] [18] [19]. This binding energy serves as a unique fingerprint for each element and its chemical environment, forming the basis for interpreting XPS spectra to extract elemental composition, chemical state information, and empirical formulas.

Experimental Protocol for XPS Analysis

Sample Preparation and Handling

Proper sample preparation is critical for obtaining reliable XPS data. Samples must be compatible with ultra-high vacuum (UHV) conditions (typically 10⁻⁷ Pa or lower), although ambient-pressure XPS is an emerging area that allows analysis at higher pressures [6]. The sample surface should be representative of the material being studied and free from adventitious contamination that could mask the true surface composition. For insulating materials, charge compensation is essential to neutralize positive charge accumulation that occurs due to electron emission [20]. This is typically achieved using a low-energy electron flood gun in combination with the XPS instrument's charge neutralization system. Sample size limitations depend on instrument design, with most instruments accepting samples ranging from millimeters to several centimeters in size [6]. Both organic and inorganic materials can be analyzed, including polymers, metals, ceramics, glasses, and biological samples, though each requires specific preparation considerations [6] [19].

Data Acquisition Workflow

The following workflow outlines the standard protocol for acquiring and processing XPS data:

- Survey Spectrum Collection: Begin with a broad energy range scan (typically 0-1100 eV or 0-1400 eV) to identify all elements present on the surface except hydrogen and helium [19]. Acquisition times typically range from 1-20 minutes [6].

- High-Resolution Regional Scans: Collect narrow window spectra for each element identified in the survey scan at higher energy resolution to resolve chemical state information. Allocate 1-15 minutes per region, with multiple sweeps often required for adequate signal-to-noise ratio [6].

- Energy Scale Calibration: Reference the energy scale to a peak with known binding energy. The adventitious hydrocarbon C 1s peak at 284.8 eV is commonly used, though alternatives like the O 1s peak in oxides or F 1s in fluorides may be more appropriate depending on the sample [21].

- Charge Compensation Optimization: For insulating samples, optimize the charge neutralizer settings to produce the narrowest peak full width at half maximum (FWHM) possible, indicating minimal charging [21].

- Quantitative Analysis: Use appropriate relative sensitivity factors (RSF) and intensity calibration specific to the instrument and X-ray source. Ensure the correct RSF library is loaded in the analysis software [21].

- Data Validation: Check for potential issues such as sample degradation, differential charging, peak overlaps, or the presence of Auger lines that might complicate interpretation [6] [21].

Figure 1: Standard XPS Data Acquisition and Analysis Workflow

Advanced XPS Techniques

For more specialized analytical needs, several advanced XPS techniques can be employed:

- Angle-Resolved XPS (ARXPS): Varies the emission angle at which electrons are collected to obtain depth resolution for ultra-thin films (1-10 nm) without sputtering [20].

- XPS Depth Profiling: Combines alternating cycles of ion beam sputtering and XPS analysis to determine composition as a function of depth [6] [20].

- XPS Imaging/Mapping: Creates spatial images showing the distribution of specific elements or chemical states across a surface [20].

- Small Area XPS (SAXPS): Focuses analysis on small features (down to 10-30 µm) on a solid surface using focused X-ray beams [20].

Interpretation of Elemental Composition

Peak Identification and Elemental Determination

The first step in interpreting XPS spectra is identifying elements present in the sample by matching the binding energies of peaks in the survey spectrum to known elemental transitions. Each element produces a set of characteristic XPS peaks corresponding to their electron configurations (e.g., 1s, 2s, 2p, 3s, etc.) [6]. Table 1 shows the characteristic binding energy ranges for principal photoelectron lines of common elements. Peaks from the XPS spectra give the relative number of electrons with a specific binding energy, with peak heights correlating to elemental concentration [18]. For accurate quantification, the intensity of each elemental peak must be corrected using relative sensitivity factors (RSFs) that account for differences in photoelectron cross-sections, mean free paths, and instrument transmission functions [21].

Table 1: Characteristic Binding Energy Ranges for Principal XPS Peaks of Common Elements

| Element | Orbital | Binding Energy Range (eV) | Characteristics |

|---|---|---|---|

| Carbon | C 1s | 284-292 | Reference peak for adventitious carbon at 284.8 eV; chemical shifts indicate bonding |

| Oxygen | O 1s | 528-536 | Metal oxides ~530 eV; organic oxygen ~532-533 eV |

| Nitrogen | N 1s | 398-404 | Organic nitrogen ~399-400 eV; nitrides ~397 eV |

| Silicon | Si 2p | 99-106 | Elemental Si 99 eV; SiO₂ 103-104 eV |

| Fluorine | F 1s | 684-689 | Highly electronegative; useful for referencing |

| Sulfur | S 2p | 160-170 | Distinguish between sulfate (~168 eV) and sulfide (~162 eV) |

Quantitative Composition Analysis

Quantitative analysis in XPS involves converting peak intensities to atomic concentrations using the formula:

Atomic % (A) = (Iₐ / Sₐ) / Σ(Iₙ / Sₙ) × 100%

where Iₐ is the integrated peak area for element a, Sₐ is the relative sensitivity factor for element a, and the summation is over all detected elements [6]. Under optimal conditions, the quantitative accuracy for major peaks (comprising 10-20% or more of the total signal) is 90-95%, while weaker signals may have accuracies of 60-80% of the true value [6]. Detection limits typically range from 0.1-1.0 atomic % (1000-10,000 ppm), though lower limits can be achieved in favorable circumstances with long collection times [6]. Several factors affect quantitative accuracy, including signal-to-noise ratio, peak intensity, accuracy of relative sensitivity factors, surface volume homogeneity, and correction for the energy dependence of electron mean free path [6].

Interpretation of Chemical State Information

Chemical Shifts and Bonding Environment

Chemical state information is derived from small shifts in binding energy (typically 0.1-4 eV) caused by changes in the chemical environment of the atom [19]. When an atom enters a chemical bond, the binding energy of its core electrons changes due to alterations in the valence electron distribution, which affects the electrostatic screening of the core electrons. Atoms in higher oxidation states or bonded to more electronegative elements typically exhibit higher binding energies due to increased effective positive charge on the atom. For example, the carbon 1s spectrum can reveal different carbon functional groups: C-C/C-H at 284.8 eV, C-O at 286.0-286.5 eV, C=O at 287.5-288.0 eV, and O-C=O at 288.5-289.0 eV [22]. Similarly, silicon shows distinct 2p binding energies for elemental silicon (99 eV), silicon nitride (101.5 eV), silicon oxynitride (102-103 eV), and silicon dioxide (103-104 eV) [22].

Spin-Orbit Splitting and Peak Parameters

For elements with p, d, or f orbitals, photoelectron peaks exhibit spin-orbit splitting due to coupling between the electron's spin and orbital angular momentum. This splitting produces doublets with characteristic area ratios and separations: p peaks split into p₃/₂ and p₁/₂ with a 2:1 area ratio; d peaks split into d₅/₂ and d₃/₂ with a 3:2 area ratio; and f peaks split into f₇/₂ and f₅/₂ with a 4:3 area ratio [21]. The full width at half maximum (FWHM) of peaks also provides chemical information, with pure metals typically having the narrowest peaks (0.5-1.0 eV), inorganic compounds having intermediate widths (0.5-1.5 eV), and organic compounds having the broadest peaks (1.0-2.0 eV or larger) [21]. When performing peak fitting, constraints based on these known parameters should be applied to produce chemically meaningful results.

Table 2: Spin-Orbit Splitting Parameters for Common Elements

| Element | Orbital | Spin-Orbit Components | Area Ratio | Separation (eV) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sodium | Na 1s | No splitting | N/A | N/A |

| Phosphorus | P 2p | 2p₃/₂, 2p₁/₂ | 2:1 | 0.8-0.9 |

| Sulfur | S 2p | 2p₃/₂, 2p₁/₂ | 2:1 | 1.2 |

| Chlorine | Cl 2p | 2p₃/₂, 2p₁/₂ | 2:1 | 1.6 |

| Chromium | Cr 2p | 2p₃/₂, 2p₁/₂ | 2:1 | 9.0-9.5 |

| Copper | Cu 2p | 2p₃/₂, 2p₁/₂ | 2:1 | 19.8-20.0 |

| Gold | Au 4f | 4f₇/₂, 4f₅/₂ | 4:3 | 3.7 |

Determining Empirical Formulas from XPS Data

Calculation Methodology

The empirical formula of a material can be determined from quantitative XPS data by converting atomic percentages into stoichiometric ratios. The process involves:

- Quantification: Obtain atomic percentages for all detected elements using the quantitative analysis method described in Section 3.2.

- Normalization: Select a key element (typically the primary cation or most abundant element besides oxygen) and normalize all other elemental concentrations relative to this element.

- Ratio Calculation: Divide each elemental atomic percentage by the atomic percentage of the reference element to obtain stoichiometric ratios.

- Rounding: Round ratios to the nearest whole numbers or simple fractions to obtain the empirical formula.

For example, if analysis of a calcium phosphate material yields Ca at 12.5%, P at 7.5%, and O at 35.0% (with other elements making up the remainder), the stoichiometric ratios would be Ca:P:O = 1:0.6:2.8, which rounds to Ca:P:O = 1:0.6:2.8, suggesting a hydroxyapatite-like composition of Ca₁₀(PO₄)₆(OH)₂ when multiplied by appropriate factors. It is important to note that XPS-derived empirical formulas represent the surface composition, which may differ from the bulk composition, especially for materials with surface segregation, contamination, or oxidation layers.

Considerations for Accurate Formula Determination

Several factors must be considered when determining empirical formulas from XPS data:

- Hydrogen and Helium Detection: XPS cannot detect hydrogen and helium, so empirical formulas derived from XPS data necessarily exclude these elements [6] [19]. This limitation must be acknowledged when reporting results.

- Surface Sensitivity: Since XPS probes only the top 1-10 nm of a material, the empirical formula represents the surface composition rather than the bulk [20].

- Accuracy Limitations: The accuracy of empirical formulas depends on the quantitative accuracy of the elemental concentrations, which is typically 90-95% for major elements but may be lower for minor constituents [6].

- Chemical State Considerations: The empirical formula should be consistent with the chemical states identified through high-resolution spectra. For example, a material containing both sulfide and sulfate species should account for both forms of sulfur in the interpretation.

Common Artifacts and Analysis Errors

Despite its apparent simplicity, XPS data interpretation is prone to several common errors and artifacts that can lead to incorrect conclusions:

- Improper Peak Fitting: One of the most common errors is overfitting spectra with too many components or using physically unrealistic parameters [21]. Peaks cannot be narrower than the X-ray linewidth (~0.25 eV for monochromatic Al Kα), and most peaks fall between 0.5-2.0 eV FWHM [21].

- Incorrect Charge Referencing: Using inappropriate reference peaks or misapplying charge correction can shift all binding energies, leading to incorrect elemental identification and chemical state assignment [21].

- Peak Overlaps: Many elements have peaks that overlap in energy, such as Pb 4f and Al 2p, or Cu 3p and Na KLL Auger peaks [21]. These overlaps must be identified and accounted for during analysis.

- Differential Charging: On heterogeneous insulating samples, different regions may charge to different potentials, causing peak broadening and distortion that complicates interpretation [21].

- Sample Degradation: Some materials, particularly polymers, certain catalysts, and fine organics, can degrade under X-ray irradiation, leading to time-dependent changes in spectra [6].

The XPS Scientist's Toolkit

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for XPS Analysis

| Item | Function/Application |

|---|---|

| Monochromatic Al Kα X-ray Source (1486.7 eV) | Standard high-energy resolution excitation source for core-level spectroscopy |

| Charge Neutralization System | Electron flood gun for stabilizing potential on insulating samples |

| Relative Sensitivity Factor (RSF) Library | Database for converting peak intensities to atomic concentrations |

| Argon Gas Cluster Ion Source | Sputtering source for depth profiling of organic and delicate materials |

| Certified Reference Materials | Standards for instrument calibration and validation (Au, Cu, Ag) |

| Conductive Adhesive Tapes | Sample mounting for electrical grounding of non-conductive materials |

| Ultra-High Vacuum System | Environment for electron detection without scattering (10⁻⁷ to 10⁻⁹ Pa) |

| High-Resolution Electron Energy Analyzer | Measurement of photoelectron kinetic energies with ~0.5 eV resolution |

XPS provides powerful capabilities for determining the elemental composition, chemical states, and empirical formulas of material surfaces. By following standardized protocols for data acquisition and interpretation, researchers can extract valuable information about their samples with quantitative accuracy. Proper attention to experimental details such as charge referencing, peak fitting constraints, and awareness of common artifacts is essential for obtaining reliable results. As XPS continues to evolve with techniques like ambient-pressure analysis and improved spatial resolution, its utility in solving materials characterization challenges across diverse fields continues to expand. The protocols and guidelines presented here provide a foundation for researchers to implement XPS effectively in their surface analysis investigations.

Applying XPS in Research: From Sample Preparation to Data Acquisition

Sample Handling and Preparation Protocols for Reliable Analysis

X-ray Photoelectron Spectroscopy (XPS), also known as Electron Spectroscopy for Chemical Analysis (ESCA), is a highly surface-sensitive analytical technique that provides valuable quantitative and chemical state information from the top 1-10 nanometers of a material's surface [23] [24]. The exceptional surface sensitivity of XPS, with an average analysis depth of approximately 5 nm, makes proper sample handling and preparation absolutely critical for obtaining reliable analytical data [23]. Unlike techniques with greater analysis depths such as SEM-EDX (which analyzes 0.5-2 microns deep), XPS exclusively probes the outermost atomic layers, meaning even minimal surface contamination or improper preparation can significantly compromise results [25]. This application note establishes detailed protocols for sample handling and preparation to ensure the integrity of XPS analysis within research and drug development contexts.

Critical Pre-Analysis Considerations

Avoiding Sample Contamination and Damage

The fundamental principle of XPS sample preparation is to preserve the true surface chemistry of the material as it exists in its application environment. Contamination control begins with understanding and avoiding common sources of interference:

- Avoid Electron Beam Techniques Prior to XPS: The region of interest for XPS analysis must not be exposed to electron beam methods such as SEM-EDX or Auger electron spectroscopy beforehand. The electron beam can cause carbon contamination thick enough to obscure the true surface chemistry and create reactive sites that alter surface composition [25].

- Limit ToF-SIMS Exposure: While Time-of-Flight Secondary Ion Mass Spectrometry (ToF-SIMS) is also surface-sensitive (1-3 nm), analysis times exceeding 4-5 minutes can degrade the surface chemistry intended for XPS analysis [25].

- X-ray Induced Damage: Although less damaging than electron beams, monochromatic X-rays can cause slight degradation to certain materials after many hours of exposure or when using high X-ray flux density. Particularly sensitive materials include polymers (PVC, poly-acrylic acid, Teflon), high oxidation state chemicals, and some catalysts [25]. Non-monochromatic X-ray sources cause more significant damage due to higher operating temperatures [25].

Surface scientists recognize several recurring contamination sources that must be controlled during sample preparation:

Table 1: Common Surface Contaminants and Their Sources

| Contaminant Type | Common Sources |

|---|---|

| Hydrocarbons | Pump oil, greasy fingerprints, dirty desiccators, contaminated solvents [25] [26] |

| Silicones | Inappropriate gloves, glass-fitting-grease, hair, hand lotion [25] [26] |

| Salts | Improper rinsing, exposure to inadequately purified water [26] |

Sample Preparation Methods and Protocols

Sample Handling and Mounting Procedures

Proper sample handling begins with using appropriate materials and techniques to minimize introduction of contaminants:

- Glove Selection: Use only polyethylene gloves or other non-powdered, clean gloves specifically approved for surface science. Many common gloves contain silicones that can transfer to samples and contaminate surfaces [26].

- Tool Cleaning: All utensils (tweezers, cutters, etc.) must be thoroughly cleaned before use to remove hydrocarbon and silicone contaminants. Regular cleaning by sonication in isopropyl alcohol (IPA) is recommended [26].

- Sample Mounting: For most XPS applications, samples can be mechanically attached to specimen mounts without special preparation. However, preserving the "as-received" surface condition is crucial, as vital information often resides in the native surface [26]. The largest typically accommodated sample mount is approximately 8 cm (3.3 inches) in diameter, though most instruments require smaller samples [25].

- Sample Identification: Mark analysis regions using a carbide tip to scribe a circle (2-3 mm) around the feature of interest. Avoid using Sharpie marking pens directly on the analysis area, as they can introduce contaminants [25].

Preparation Techniques for Different Sample Types

Powder Samples

Powdered materials require specific preparation techniques to ensure representative surface analysis:

- Pressed Pellet Method: Press powder into clean, high-purity indium foil. This increases signal counts, improves charge compensation, and creates a smooth surface for analysis [25].

- Drop-Casting: Dissolve powder in a suitable solvent and drop-cast onto the surface of a clean silicon wafer [26].

- Alternative Methods: For powders not amenable to the above methods, sprinkle onto sticky carbon tape or press into a tablet using a pellet press [26].

Solid Samples

Various techniques exist for exposing bulk chemistry or preparing specific solid sample types:

- Fracturing: Break open samples using a hammer in air, fracture under solvent, or use liquid nitrogen fracturing for brittle materials. Note that fracturing may occur along grain boundaries that may not be representative of bulk material [25] [26].

- Scraping: Scrape the surface with a freshly cleaned single-edge razor blade to remove surface contamination and expose underlying material. This can be performed in air or under solvent [25].

- Abrasion: Use fine sandpaper, a file, or a razor blade to remove surface material. To prevent oxidation of active materials, perform abrasion in an inert atmosphere or while immersing the sample in an appropriate volatile organic solvent [26].

- Grinding: Grind coarse particles into fine powder using a mortar and pestle to expose bulk chemistry. Grind slowly to minimize heat generation that could alter chemistry [26].

Cleaning Treatments

Various cleaning methods can remove specific types of surface contaminants:

- Solvent Cleaning: Use freshly distilled solvents to avoid contaminating surfaces with high boiling point impurities. Light hydrocarbon solvents like hexane are least likely to alter surfaces [26].

- Plasma Cleaning: Exposure to air-plasma corona using a laboratory Tesla coil can remove organic contaminants from insulator surfaces [25].

- Ion Etching: Use light ion etching to remove approximately 8 nm of adventitious carbon contamination, or strong ion etching to remove 25 nm or more of surface material. Note that ion sputtering may cause changes in surface chemistry [25].

Table 2: Sample Preparation Methods and Their Applications

| Preparation Method | Primary Function | Important Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| As-Received Condition | Preserves native surface chemistry | Essential for contamination analysis and failure analysis [25] [26] |

| Light Ion Etch | Removes ~8 nm adventitious carbon | Reveals subsurface information without significant material removal [25] |

| Solvent Cleaning | Removes soluble contaminants | Use freshly distilled solvents to avoid impurity deposition [26] |

| Powder Pressing | Creates analyzable surface from powders | Press into indium foil for best results [25] |

| Fracturing/Scraping | Exposes bulk chemistry | May create unrepresentative surfaces along grain boundaries [26] |

Sample Storage and Shipping Protocols

Proper storage and transportation are essential for maintaining surface integrity before analysis:

- Storage Containers: Store samples in clean tissue culture polystyrene (TCPS) dishes, clean glass vials, or new aluminum foil. Avoid plastic bags and most plastic containers, which can introduce contaminants [25] [26].

- Shipping Preparation: Secure samples in TCPS dishes using a small amount of double-sided tape on only a tiny corner of the sample. Ensure samples can be easily removed without damage [26].

- Documentation: Include a detailed sample summary sheet listing all samples, their structures, and the chemistry of the surface-bound species. Without structural information, accurate analysis of XPS data is difficult [26].

- Control Samples: Always include appropriate control samples, such as underlying substrate alone or solvent-exposed controls, to enable proper data interpretation [26].

Experimental Workflow for XPS Analysis

The following diagram illustrates the comprehensive workflow for proper XPS sample handling and preparation, from initial planning through data acquisition:

Essential Materials for XPS Sample Preparation

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for XPS Sample Preparation

| Material/Reagent | Function in Preparation | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| High-Purity Indium Foil | Substrate for pressing powdered samples | Creates smooth, analyzable surface from powders; superior to carbon tape [26] |

| Polyethylene Gloves | Hand protection without contamination | Avoids silicone transfer from many common gloves [26] |

| Isopropyl Alcohol (IPA) | Cleaning agent for tools and surfaces | Use freshly distilled 90-100% IPA to remove soluble contaminants [25] |

| Silicon Wafers | Clean substrate for drop-casting | Provides atomically flat, reproducible surface for liquid samples [26] |

| Aluminum Foil | Clean storage and transport medium | New, clean foil avoids contaminant transfer from plastic containers [25] |

| Tissue Culture Polystyrene Dishes | Sample storage and shipping containers | Sealed with parafilm; superior to plastic bags for maintaining cleanliness [26] |

Analytical Conditions and Data Quality Assurance

Standard XPS Analysis Parameters

For consistent and comparable results, standard analytical conditions should be employed:

- X-ray Beam Size: 500 × 800 μm for large area analysis, down to 50 × 150 μm for small features [25]

- Survey Spectra Range: -10 to 1100 eV (extended to 1400 eV if arsenic or gallium are expected) [25]

- Electron Take-off Angle: 35 degrees maximizes surface information [25]

- Detection Limits: 0.1 to 1.0 atomic percent, depending on element and kinetic energy of the peak [25]

Quality Control Measures

Implementing rigorous quality control procedures ensures data reliability:

- Duplicate Samples: Submit duplicate samples when possible, as samples can be damaged during transport or loading [26].

- Control Samples: Always include appropriate controls, such as the underlying substrate alone or solvent-exposed controls [26].

- Sequential Analysis: For troubleshooting applications, analyze the "bad" area first, then compare to "good" areas on the same sample when possible [25].

- Outgassing Management: For materials that tend to outgas (polymers, "wet" silicones, spongy materials), reduce sample size to facilitate pumping to required vacuum levels (<5×10⁻⁹ Torr) [26].

Proper sample handling and preparation represent the most critical factors in obtaining reliable, reproducible XPS data. The extreme surface sensitivity of this technique demands meticulous attention to contamination control, appropriate sample-specific preparation methods, and careful documentation throughout the process. By adhering to these established protocols, researchers and drug development professionals can ensure that their XPS analysis accurately reflects the true surface chemistry of their materials rather than artifacts of improper handling. Maintaining consistency in sample preparation across experiments is essential for meaningful comparison of results and drawing valid scientific conclusions about surface composition and chemistry.

Conducting Surface Surveys and High-Resolution Regional Scans

X-ray Photoelectron Spectroscopy (XPS) is a highly surface-sensitive quantitative spectroscopic technique that measures the elemental composition, empirical formula, chemical state, and electronic state of elements within a material [10] [27]. As a surface analysis technique, XPS provides critical information from the top 1–10 nm of a material, making it indispensable for research and quality control across numerous fields including electronics, healthcare, automotive, aerospace, and materials science [10] [28]. The technique operates on the photoelectric effect principle, where X-rays irradiate a solid surface, causing the emission of photoelectrons whose kinetic energy is measured and related to their binding energy within the parent atom [27] [29].

Two fundamental measurement modes in XPS analysis are the surface survey (or wide scan) and high-resolution regional scans (or narrow scans). The survey scan provides a comprehensive overview of all detectable elements within the analysis volume, while high-resolution scans deliver detailed chemical state information for specific elements of interest. These complementary approaches form the cornerstone of rigorous XPS characterization, enabling researchers to extract both elemental and chemical bonding information from material surfaces [1].

Theoretical Foundations

Fundamental Principles of XPS

The fundamental relationship in XPS follows from the photoelectric effect, expressed as:

BE = hν – KE

Where BE is the electron binding energy, hν is the incident X-ray energy, and KE is the measured kinetic energy of the emitted photoelectron [29]. Crucially, the binding energy represents the difference in energies between the N-electron initial (un-ionized) state and the (N-1)-electron final (ionized) state:

BE = E(N-1, final) – E(N, initial) [29]

This relationship highlights that XPS binding energies are rigorously many-electron quantities rather than simple one-electron measurements, accounting for the rich chemical information contained in XPS spectra [29].

Initial and Final State Effects

Proper interpretation of XPS data requires understanding both initial state and final state effects:

- Initial state effects refer to the electronic structure of the un-ionized system, including chemical bonding, charge transfer, and the formal oxidation state of the atom [29].

- Final state effects arise from the response of the system to the creation of the core hole during photoemission, including core-hole screening and relaxation phenomena [29].

The interplay between these effects governs the observed binding energy shifts and spectral complexities, necessitating sophisticated interpretation approaches, especially for complex materials like metal oxides [29].

Experimental Protocols

Pre-Analysis Planning and Sample Preparation

Question Definition: Clearly define the analytical questions before measurement. Determine whether the analysis requires elemental identification, chemical state determination, depth profiling, or spatial mapping [1].

Sample Compatibility Assessment:

- Evaluate sample size compatibility with the XPS instrument

- Determine electrical conductivity (conductive, semiconducting, or insulating)

- Assess vacuum compatibility and vapor pressure

- Consider radiation sensitivity (potential for X-ray damage) [1]

Sample Handling and Preparation:

- Use clean tools and gloves to minimize contamination (some gloves contain transferable elastomers) [30]

- For powders, consider mounting on adhesive tapes or pressing into indium foil

- For insulating samples, plan for charge compensation strategies

- Document all pre-treatment procedures for reporting [1]

Instrument Setup and Performance Verification

Instrument Calibration:

- Verify energy scale calibration using standard reference materials (e.g., clean Au, Ag, or Cu foils)

- Confirm analyzer work function settings

- Check intensity/response function using standard materials [1]

Source Selection:

- Choose between monochromatic and non-monochromatic X-ray sources based on analysis requirements

- Monochromatic sources offer higher energy resolution and reduced bremsstrahlung background

- Non-monochromatic sources may provide higher photon flux but can cause more sample damage due to heating and high-energy X-rays [30]

Table 1: Key Instrument Parameters for XPS Analysis

| Parameter | Survey Scans | High-Resolution Scans | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pass Energy | 50-100 eV | 10-50 eV | Higher pass energy increases sensitivity but reduces resolution |

| Step Size | 0.5-1.0 eV | 0.05-0.1 eV | Finer steps for better definition of spectral features |

| Analysis Area | 100×100 µm to 1×1 mm | 100×100 µm to 500×500 µm | Smaller areas require longer acquisition times |

| Number of Scans | 1-4 scans | 4-20 scans | Signal averaging improves S/N ratio |

| Dwell Time | 50-100 ms | 100-200 ms | Longer dwell times improve S/N but increase acquisition time |

Surface Survey Scan Protocol

Objective: To identify all elements present on the sample surface within the detection limits of XPS (typically ~0.1-1.0 atomic %).

Acquisition Parameters:

- Energy range: 0-1100 eV or 0-1400 eV (covering all core levels for most elements)

- Pass energy: 50-100 eV (high sensitivity mode)

- Step size: 0.5-1.0 eV

- Number of scans: 1-4 (optimizing S/N ratio versus time) [30]

Data Interpretation:

- Identify all detectable elements using known binding energy tables [30]

- Note relative peak intensities for semi-quantitative assessment

- Check for instrumental artifacts (X-ray ghosts, energy loss features)