XPS vs AES: A Comprehensive Guide to Surface Analysis Techniques for Material Science and Biomedical Research

This article provides researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals with a detailed comparison of X-ray Photoelectron Spectroscopy (XPS) and Auger Electron Spectroscopy (AES).

XPS vs AES: A Comprehensive Guide to Surface Analysis Techniques for Material Science and Biomedical Research

Abstract

This article provides researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals with a detailed comparison of X-ray Photoelectron Spectroscopy (XPS) and Auger Electron Spectroscopy (AES). It covers the fundamental principles, methodological applications, and practical troubleshooting for both techniques. The guide explores their specific uses in characterizing biomedical materials, thin films, and semiconductors, supported by current market trends and technological advancements like machine learning and multimodal integration. It concludes with a direct comparison to help professionals select the optimal technique for their specific surface analysis challenges, from foundational research to industrial quality control.

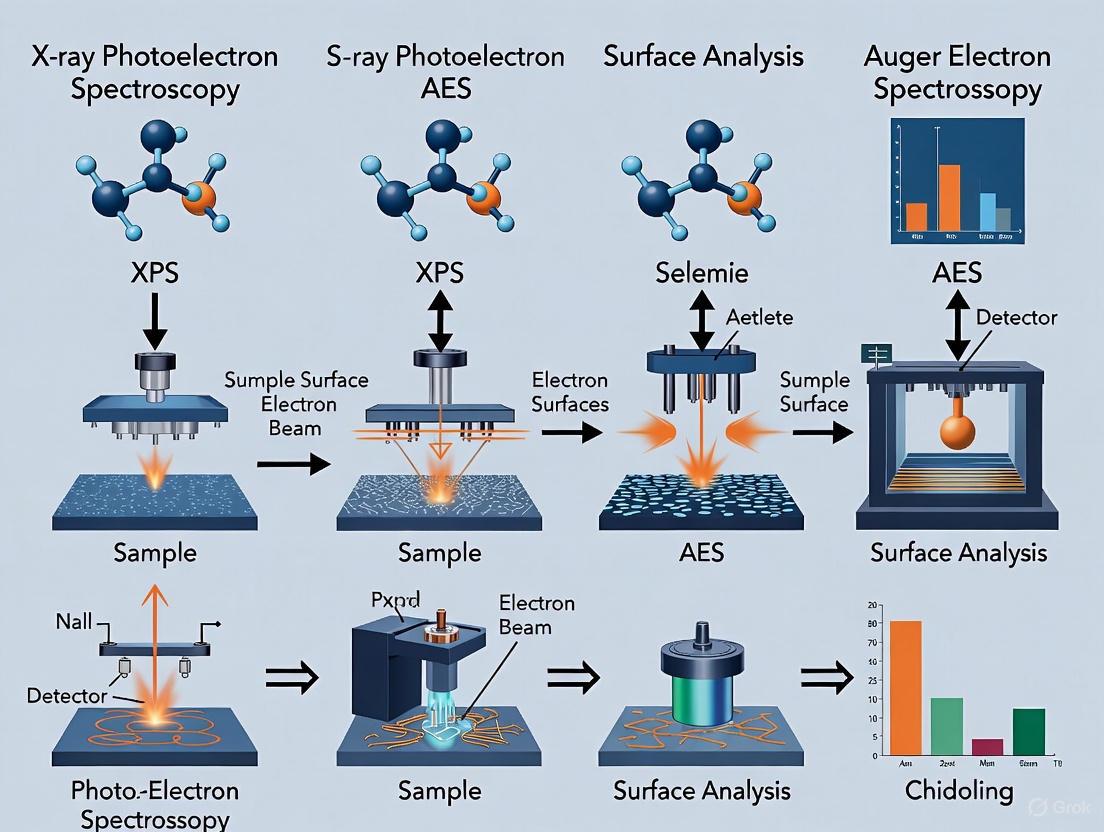

Understanding Surface Analysis: Core Principles of XPS and AES

The fundamental operation of X-ray Photoelectron Spectroscopy (XPS) and Auger Electron Spectroscopy (AES) relies on two distinct electron emission processes: the photoelectric effect and the Auger process. Both techniques are surface-sensitive analytical methods used to determine the elemental composition and chemical state of materials, but they are initiated through different mechanisms and provide complementary information [1] [2]. The photoelectric effect forms the basis for XPS, while the Auger process, which can occur following either X-ray or electron bombardment, is the namesake and primary signal source for AES [3]. Understanding these core principles is essential for researchers and scientists selecting the appropriate technique for specific surface analysis challenges, particularly in fields like drug development and materials science where surface properties critically influence performance and functionality.

The Photoelectric Effect in XPS

Fundamental Mechanism

The photoelectric effect is the fundamental physical process underpinning X-ray Photoelectron Spectroscopy (XPS). This process involves the ejection of a core electron from an atom after it absorbs an X-ray photon with sufficient energy [2] [3]. The interaction is summarized by the equation: m + hν → m+* + e−, where m represents an atom in the material, hν is the incident X-ray photon, m+* is the resulting excited ion, and e− is the ejected photoelectron [3]. The kinetic energy (KE) of this ejected photoelectron is determined by the equation KE = hν - BE, where hν is the known energy of the incident X-ray photon and BE is the binding energy of the electron within its specific atomic orbital [3]. Since the binding energy is characteristic of both the element and the specific electron shell from which it originated, measuring the kinetic energy of the emitted electrons allows for precise elemental identification and chemical state analysis [1] [3].

Information Content and Chemical Shifts

A key strength of the photoelectric effect in XPS analysis is its sensitivity to the chemical environment of the atom. The binding energy of an electron experiences small but measurable shifts depending on the oxidation state and chemical bonding of the atom. This phenomenon, known as the "chemical shift," enables XPS to distinguish between different chemical states of the same element [3]. For example, the binding energy for molybdenum 3d electrons is 227.6 eV in its elemental form, but shifts to 229.6 eV in the +4 oxidation state and 232.7 eV in molybdenum trioxide (+6 oxidation state) [3]. This capability to provide quantitative data on oxidation states makes XPS exceptionally powerful for studying surface chemistry, catalysis, corrosion, and functionalized materials [1].

The Auger Process in AES

Fundamental Mechanism

The Auger process, central to Auger Electron Spectroscopy (AES), is a multi-stage relaxation phenomenon that occurs after an atom has been ionized in one of its inner shells. This initial ionization can be caused by either an incident electron or X-ray, creating an excited ion (m+) [2] [3]. The process unfolds in three distinct steps, as illustrated in Figure 1. First, the creation of a core hole occurs via electron bombardment: m + e− → m+ + 2e− [3]. Second, an electron from a higher-energy level fills the core vacancy, releasing energy. Third, instead of emitting an X-ray, this energy causes the simultaneous ejection of a third electron, known as the Auger electron [1] [3]. Critically, the kinetic energy of this emitted Auger electron is characteristic of the elements involved and is independent of the energy of the initial ionizing beam [3]. This independence distinguishes Auger electrons from the photoelectrons measured in XPS.

Information Content and Analytical Strengths

AES excels at providing high-resolution elemental mapping and depth profiling [1] [3]. Because the primary beam in AES is composed of electrons, which are easily focused, AES can achieve very high spatial resolution, making it ideal for analyzing small surface features and creating detailed maps of elemental distribution across a surface [3]. However, the standard instrumentation for AES prioritizes rapid analysis for surface mapping, which often sacrifices the spectral resolution needed to detect the subtle chemical shifts that are readily observed in XPS [3]. Consequently, AES is primarily used for elemental analysis rather than detailed chemical state identification, though chemical state information is present in the Auger spectra [1].

Comparative Analysis: Photoelectric Effect vs. Auger Process

Direct Comparison of Principles and Capabilities

The following table summarizes the fundamental differences between the photoelectric effect (for XPS) and the Auger process (for AES), highlighting their distinct origins, energy dependencies, and the type of information they provide.

Table 1: Fundamental Comparison Between the Photoelectric Effect and the Auger Process

| Feature | Photoelectric Effect (XPS) | Auger Process (AES) |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Process | Photoionization by X-rays [2] [3] | Relaxation after initial ionization (by electron or X-ray) [3] |

| Initial Excitation | X-ray photon absorption [2] | Electron beam bombardment (typically) [1] [3] |

| Emitted Electron | Photoelectron [2] | Auger electron [1] |

| Kinetic Energy Dependence | Depends on incident X-ray energy [3] | Independent of primary beam energy [3] |

| Key Information | Elemental identity, chemical state, oxidation state [1] [3] | Elemental identity and composition [1] [3] |

| Chemical State Analysis | Excellent (via chemical shifts) [3] | Limited with standard instrumentation [3] |

Practical Technique Comparison: XPS vs. AES

Building on the core physical principles, the practical implementation of XPS and AES reveals distinct advantages and limitations, guiding technique selection for specific research goals.

Table 2: Practical Comparison of XPS and AES Analytical Techniques

| Characteristic | XPS | AES |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Excitation Source | X-rays [1] [2] | Electron beam [1] [2] |

| Detected Particle | Photoelectrons [2] | Auger electrons [1] [2] |

| Spatial Resolution | Lower (X-ray beam is hard to focus) [3] | Very High (electron beam is easily focused) [3] |

| Chemical State Info | Excellent [1] [3] | Limited [1] [3] |

| Best For | Quantitative analysis, oxidation states, thin films [1] | Surface mapping, micro-area analysis, depth profiling [1] [3] |

| Sample Limitations | Suitable for conductors, semiconductors, and insulators [1] | Primarily for conductors and semiconductors (insulators charge) [3] |

| Detection Limit | ~0.1-1 at% [3] | Better for most elements (due to highly focused beam) [3] |

| Depth of Analysis | Top ~10 nm [1] | More surface-sensitive (shorter mean free path of Auger electrons) [2] |

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Typical XPS Experimental Workflow

The following diagram outlines the standard workflow for conducting an analysis using X-ray Photoelectron Spectroscopy, from sample preparation to data interpretation.

Figure 2: XPS Experimental Workflow

Detailed XPS Methodology:

- Sample Preparation: Samples must be solid and compatible with ultra-high vacuum (UHV). Preparation involves cleaning to remove surface contaminants and mounting on a suitable holder, often using conductive tape or clamps to minimize charging [1].

- Ultra-High Vacuum (UHV): The analysis must be performed in a UHV environment (typically better than 10⁻⁹ mbar) to minimize scattering of the ejected photoelectrons by gas molecules and to prevent surface contamination during measurement [1].

- X-ray Irradiation: The sample is irradiated with a monochromatic or non-monochromatic X-ray source, such as Al Kα (1486.6 eV) or Mg Kα (1253.6 eV) [1] [4]. This causes the ejection of photoelectrons via the photoelectric effect.

- Energy Analysis and Detection: The kinetic energy of the ejected photoelectrons is measured using a hemispherical electron energy analyzer. The analyzer applies a sweeping voltage to separate electrons by energy, which are then counted by a detector [3].

- Data Interpretation: The resulting spectrum plots electron count versus binding energy. Elemental identification is achieved by matching peak positions to known binding energies. Chemical state information is derived from precise peak position shifts (chemical shifts) and peak shape analysis [3].

Typical AES Experimental Workflow

The standard workflow for Auger Electron Spectroscopy shares some similarities with XPS but differs critically in the source of excitation and its analytical focus.

Figure 3: AES Experimental Workflow

Detailed AES Methodology:

- Sample Preparation: Samples for AES are typically limited to conductors and semiconductors to prevent surface charging from the primary electron beam. Insulators are difficult to analyze without specialized charge neutralization systems [3].

- Ultra-High Vacuum (UHV): Like XPS, AES requires a UHV environment for the same fundamental reasons [1].

- Electron Beam Bombardment: A finely focused, high-energy (typically 3-20 keV) electron beam is scanned across the sample surface. This beam causes the initial ionization that leads to Auger electron emission [1] [3].

- Signal Detection and Enhancement: Auger electron signals are often weak and superimposed on a high background of secondary electrons. To enhance the signal-to-noise ratio, the data is typically presented in the differentiated (derivative) mode [3].

- Spatial Resolution and Mapping: The primary strength of AES is its high spatial resolution (can be down to nanometers). By rastering the focused electron beam and recording the Auger signal intensity at each point, detailed two-dimensional elemental maps can be generated [1] [3]. When combined with ion sputtering, AES is highly effective for three-dimensional depth profiling [3].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

The following table details key components and consumables essential for conducting XPS and AES analyses.

Table 3: Essential Materials and Reagents for XPS and AES Analysis

| Item Name | Function/Application | Technical Specification & Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Conductive Tape/Mounts | Sample fixing for XPS/AES | Carbon or metallic tapes; crucial for electrical contact to reduce charging effects. |

| Standard Reference Samples | Energy scale calibration | Clean gold (Au 4f₇/₂ at 84.0 eV) or copper (Cu 2p₃/₂ at 932.7 eV) foils for XPS. |

| X-ray Anodes | X-ray source for XPS | Replaceable anodes (Aluminum or Magnesium) generating characteristic Kα X-rays [4]. |

| Electron Guns | Primary beam source for AES | Thermionic (e.g., LaB₆) or field emission guns (FEG) for high spatial resolution. |

| Ion Sputter Gun | Surface cleaning & depth profiling | Argon (Ar⁺) ion source to etch surface layers; requires high-purity argon gas. |

| Hemispherical Analyzer (HSA) | Electron energy analysis | Core component of XPS systems; measures kinetic energy of photoelectrons [3]. |

| Cylindrical Mirror Analyzer (CMA) | Electron energy analysis | Common electron energy analyzer used in many AES systems [3]. |

| UHV-Compatible Materials | Chamber and sample holder construction | Made from stainless steel, high-purity copper, and other low-vapor-pressure materials. |

The photoelectric effect and the Auger process are two fundamental electron emission mechanisms that form the foundation of the powerful surface analysis techniques XPS and AES, respectively. The photoelectric effect provides exceptional chemical state information and quantitative capabilities, making XPS the preferred technique for investigating oxidation states, surface functionalization, and thin film chemistry. In contrast, the Auger process, when harnessed in AES, provides superior spatial resolution and is ideal for high-sensitivity elemental mapping and depth profiling of small surface features. The choice between these techniques is not a matter of superiority but of strategic application. Researchers must align their selection with their specific analytical needs: XPS for detailed chemical bonding information, and AES for high-resolution elemental distribution and micro-area analysis. A comprehensive surface characterization strategy in advanced research and development often leverages both techniques to obtain a complete picture of a material's surface properties.

The evolution of modern surface analysis is rooted in the pioneering work of early 20th-century physicists who discovered the fundamental phenomena underlying today's sophisticated instrumentation. X-ray Photoelectron Spectroscopy (XPS) and Auger Electron Spectroscopy (AES) emerged as two cornerstone techniques for surface characterization, both relying on the detection of electrons emitted from a material's outermost layers (typically 1-10 nm) [1] [5]. While they share ultra-high vacuum requirements and high surface sensitivity, their distinct physical principles and historical development pathways have led to complementary analytical capabilities [1] [5]. The progression from theoretical discovery to commercially viable analytical instruments transformed our ability to understand material composition, chemical states, and elemental distribution at the nanoscale, fueling advancements across semiconductor technology, biomedicine, and materials science [6] [7] [8]. This guide traces the parallel historical development of XPS and AES, providing an objective comparison of their performance, supported by experimental data and methodologies relevant to researchers and drug development professionals.

The Foundational Discoveries and Theoretical Frameworks

The Photoelectric Effect and the Birth of XPS

The genesis of XPS lies in the photoelectric effect, first explained by Albert Einstein in 1905, for which he received the Nobel Prize in 1921. This theory established that light can eject electrons from a material, with their kinetic energy being proportional to the light's frequency. Decades later, in the 195, Kai Siegbahn and his research group at Uppsala University in Sweden developed this principle into a practical analytical technique. Their work on measuring the kinetic energy of these ejected photoelectrons with high precision demonstrated that the technique could determine not only elemental identity but also chemical state [9]. Siegbahn's pioneering contributions, which earned him the Nobel Prize in Physics in 1981, led to the technique being alternatively known as Electron Spectroscopy for Chemical Analysis (ESCA) [7].

The Auger Effect and the Emergence of AES

The foundation for AES was laid independently by Lise Meitner in 1922 and later by Pierre Auger in 1923, who discovered the radiationless transition that now bears his name. The Auger effect occurs when an electron beam strikes a material, creating a core-hole. This unstable state is filled by an electron from a higher energy level, and the released energy causes the emission of a secondary "Auger" electron [1] [5]. Unlike the photoelectric effect, this process is a three-electron phenomenon that depends on the element's internal energy levels, making it independent of the excitation source. While the effect was discovered in the 1920s, it was not until the 1960s, with the work of researchers like Larry Harris at the Bell Telephone Laboratories, that AES was developed into a viable surface analysis technique, particularly with the incorporation of cylindrical mirror analyzers for improved signal detection [1].

Table 1: Key Historical Milestones in XPS and AES Development

| Time Period | XPS Milestone | AES Milestone |

|---|---|---|

| Early 1900s | Einstein explains the photoelectric effect (1905). | Lise Meitner and Pierre Auger discover the Auger effect (1922-1923). |

| 1950s-1960s | Kai Siegbahn develops ESCA; first commercial instruments. | Larry Harris demonstrates AES as a practical surface tool. |

| 1970s-1980s | Widespread commercialization; growth in chemical state analysis. | Incorporation into surface analysis systems; use for depth profiling. |

| 1990s-2000s | Advancements in spatial resolution and monochromatic sources. | High-resolution imaging and small-area analysis capabilities refined. |

| 2010s-Present | Automation, miniaturization (benchtop systems), and AI integration. | Enhanced mapping and integration with multi-technique platforms. |

Evolution of Instrumentation and Key Technological Innovations

The journey from experimental proof-of-concept to modern instrumentation required overcoming significant technical hurdles. Early instruments for both XPS and AES were custom-built in research laboratories, requiring ultra-high vacuum (UHV) conditions to enable the emitted electrons to travel to the detector without scattering [1] [5].

For XPS, a major breakthrough was the development of monochromatic X-ray sources, which replaced simpler anode-based sources. Monochromatic Al Kα X-rays (1486.6 eV) reduced the energy breadth of the excitation source, significantly improving spectral resolution and enabling the detection of subtle chemical state differences [8]. Parallel innovations in electron energy analyzers, particularly the hemispherical capacitor analyzer (HCA), allowed for precise measurement of electron kinetic energy. More recently, the development of focusing X-ray optics has dramatically improved the spatial resolution of XPS from millimetres to tens of microns, and even sub-micron in some advanced systems, bridging a key gap with AES [5] [8].

AES instrumentation evolved around the electron gun, with advances in field emission sources enabling the electron beam to be focused to spot sizes as small as 10 nanometres, making AES a powerful tool for microanalysis and defect review [5]. The cylindrical mirror analyzer (CMA) became a popular choice for its high transmission efficiency. The integration of ion sputtering guns for controlled material removal made both XPS and AES powerful tools for depth profiling, allowing researchers to construct three-dimensional compositional maps of thin films and layered structures [1].

Technical Comparison: XPS vs. AES in Modern Research

Modern XPS and AES instruments offer distinct capabilities and limitations, making each suitable for different analytical scenarios. The choice between them depends on the specific requirements of the analysis, such as the need for chemical state information, spatial resolution, or analysis speed.

Table 2: Performance Comparison of Modern XPS and AES Techniques

| Characteristic | XPS (ESCA) | AES |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Excitation Source | X-ray photons (Al Kα, Mg Kα) | Focused electron beam (typically 3-20 keV) |

| Information Provided | Elemental identity, concentration, chemical state, and oxidation state [1] [5] [9] | Elemental identity, concentration, and elemental mapping [1] [5] |

| Spatial Resolution | 10-100 µm (conventional); sub-µm with modern microprobes [5] | < 10 nm with field emission guns [5] |

| Detection Limit | 0.1 - 1.0 atomic % [1] | 0.1 - 1.0 atomic % [1] |

| Chemical State Sensitivity | Excellent - can distinguish oxidation states (e.g., Fe²⁺ vs. Fe³⁺) [1] [5] [9] | Poor - limited chemical state information [1] [5] |

| Sample Damage | Generally low (X-ray irradiation) | Potentially high (electron beam irradiation) |

| Typical Analysis Depth | 1 - 10 nm [1] [5] [9] | 1 - 10 nm [1] [5] |

| Key Strength | Quantitative chemical state analysis [1] [9] | High-spatial resolution elemental mapping and micro-analysis [1] [5] |

| Primary Limitation | Lower spatial resolution vs. AES; can suffer from charging on insulators [1] [5] | Minimal chemical state information; electron beam can damage sensitive samples [1] [5] |

Experimental Protocols for Comparative Analysis

To objectively evaluate the performance of XPS and AES, standardized experimental protocols are essential. The following methodologies outline a typical workflow for surface characterization, applicable to materials like biomedical implants or semiconductor structures.

Protocol 1: Surface Compositional Analysis of a Biomedical Implant

Objective: To determine the surface composition and chemical states of a titanium-based biomedical implant to assess its oxide layer and potential contamination [7].

- Sample Preparation: The implant is cut to an appropriate size (typically ~1 cm x 1 cm) and mounted on a standard sample holder using conductive tape or clips. It may be ultrasonically cleaned in a solvent like isopropanol to remove adventitious carbon contamination [7].

- Instrument Setup:

- XPS: The instrument is configured with a monochromatic Al Kα X-ray source (1486.6 eV). The analyzer pass energy is set to 20-40 eV for survey scans and 10-20 eV for high-resolution regional scans to maximize signal-to-noise ratio and resolution.

- AES: A electron beam voltage of 10 kV and a beam current of 10 nA are used. The analysis area is selected using secondary electron imaging.

- Data Acquisition:

- XPS: A survey spectrum (0-1100 eV binding energy) is first acquired to identify all elements present. High-resolution spectra are then collected for the Ti 2p, O 1s, and C 1s core levels. The Ti 2p spectrum is critical for identifying TiO₂, which is a passivating and biocompatible oxide [7].

- AES: A survey spectrum (from 0 to 2000 eV kinetic energy) is acquired from a specific spot or region. Point analysis can be performed on visually distinct features, and elemental maps can be acquired for Ti, O, and C to visualize distribution.

- Data Analysis:

- XPS: Peaks are fitted using software to separate different chemical states. The position of the Ti 2p₃/₂ peak at approximately 458.5 eV confirms TiO₂. The atomic concentration of each element is calculated from peak areas and relative sensitivity factors.

- AES: Peak heights in the differential spectrum are used for semi-quantitative analysis. Elemental maps are overlaid to correlate the distribution of elements.

Protocol 2: Failure Analysis of a Semiconductor Device

Objective: To identify the cause of failure in a semiconductor device by locating and characterizing a sub-micrometre conductive bridge between two isolated metal lines [1].

- Sample Preparation: The device is opened mechanically or chemically to expose the area of interest and mounted in a specimen holder that provides a path to electrical ground to minimize charging.

- Instrument Setup:

- AES (Primary Tool): A high-brightness field emission electron gun is used. The beam energy is set to 10 kV with a low beam current (~1 nA) to minimize sample damage. The spot size is minimized for maximum spatial resolution.

- XPS (Follow-up): If needed, a small-spot XPS system with a focused X-ray probe is used on the feature identified by AES for chemical state analysis.

- Data Acquisition:

- AES: The device is first imaged using secondary electrons to locate the suspected bridge. Auger point analyses are performed on the bridge and the surrounding unaffected area. An Auger line scan or elemental map for the bridge material (e.g., Al, Cu) is acquired across the bridge to confirm its composition.

- Data Analysis:

- AES: The Auger spectrum from the bridge is compared to reference spectra to identify the elemental composition of the contaminant causing the short circuit (e.g., migration of a specific metal). The high spatial resolution of AES is crucial for confining the analysis to the narrow bridge structure.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for XPS and AES Analysis

| Item | Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Conductive Tapes & Mounting Clips | Provides electrical and thermal contact between sample and holder; ensures sample stability. | Crucial for preventing charging, especially for non-conductive samples in both XPS and AES [1]. |

| Standard Reference Materials | Used for instrument calibration and quantification. | Au foil (Au 4f₇/₂ at 84.0 eV) and Cu foil (Cu 2p₃/₂ at 932.7 eV) are common for XPS [9]. |

| Ion Sputtering Source (Ar⁺) | For in-situ sample cleaning and depth profiling by removing surface layers. | Integrated into both XPS and AES systems; parameters (energy, current) must be optimized to avoid sample damage [1]. |

| Monochromated Al Kα X-ray Source | High-energy resolution X-ray excitation for XPS. | Reduces peak full-width, enabling accurate chemical state identification [8]. |

| Field Emission Electron Gun | High-brightness, small-spot electron source for AES. | Essential for achieving <10 nm spatial resolution in AES mapping and microanalysis [5]. |

| Charge Neutralization System | Floods sample with low-energy electrons/ions to compensate for positive charge buildup. | Required for analyzing insulating materials (e.g., polymers, ceramics) in XPS [1] [5]. |

| Hemispherical Analyzer (HCA) | Measures kinetic energy of photoelectrons (XPS) or Auger electrons with high precision. | The core detector in modern XPS and some AES systems [8]. |

The historical development of XPS and AES reveals a journey from the exploration of fundamental physical phenomena to the creation of indispensable analytical tools for modern science and industry. While their core principles remain unchanged, the instrumentation has seen continuous refinement. The current market and technological trends indicate a promising future shaped by miniaturization, with the development of benchtop XPS systems [8], automation for higher throughput, and the integration of artificial intelligence (AI) and machine learning (ML) for advanced data interpretation and spectral analysis [10]. Furthermore, the combination of XPS and AES into multi-technique vacuum clusters is becoming more common, allowing researchers to leverage the complementary strengths of both techniques on the same sample without exposure to the ambient environment [8]. As materials science continues to push into the nanoscale, particularly in fields like semiconductor manufacturing (with nodes below 7 nm) and advanced biomaterials, the demand for the precise chemical and elemental surface analysis provided by XPS and AES will only intensify, ensuring their continued evolution and relevance [6] [8].

Surface analysis is a critical component of materials science, chemistry, and various industrial research fields, where the top few atomic layers of a material often dictate its performance and properties. Among the most powerful techniques for surface characterization are X-ray Photoelectron Spectroscopy (XPS) and Auger Electron Spectroscopy (AES). While both techniques provide elemental information from the outermost surface of materials, they differ significantly in their underlying physical principles, operational parameters, and the specific information they deliver. For researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, understanding these distinctions is essential for selecting the appropriate analytical method for specific research challenges. This guide provides a detailed comparison of XPS and AES, focusing on three fundamental physical parameters: analysis depth, spatial resolution, and range of detectable elements, supported by experimental data and methodological protocols.

Fundamental Principles and Technical Comparison

Physical Mechanisms

The operational principles of XPS and AES, while both involving electron emissions, originate from distinct physical processes that fundamentally shape their applications and limitations.

XPS is based on the photoelectric effect. When a sample is irradiated with X-rays (typically Al Kα or Mg Kα), core-level electrons absorb the photon energy and are ejected as photoelectrons. The kinetic energy of these photoelectrons is measured, and their characteristic binding energy is calculated using the relationship: Kinetic Energy = Photon Energy - Binding Energy - Work Function [3] [11]. This binding energy is not only elemental-specific but is also sensitive to the chemical environment of the atom, resulting in measurable chemical shifts that provide information about oxidation states and chemical bonding [3] [12].

AES relies on the Auger effect, a multi-step process initiated by a high-energy electron beam. This beam creates a core-hole vacancy. When an electron from a higher energy level fills this vacancy, the released energy can either be emitted as an X-ray or can eject a third electron, known as an Auger electron. The kinetic energy of this Auger electron is characteristic of the element from which it was emitted and is generally independent of the incident beam energy [3] [13] [11].

A key practical difference lies in the primary excitation source: XPS uses X-rays, while AES uses an electron beam. This difference is primarily responsible for their divergent capabilities in chemical state analysis and spatial resolution [3].

Comparative Technical Specifications

The table below summarizes the key physical parameters for XPS and AES, providing a direct comparison of their analytical capabilities.

Table 1: Comparison of Key Physical Parameters for XPS and AES

| Parameter | XPS (ESCA) | AES |

|---|---|---|

| Analysis Depth | ~5 nm or less [14] | ~5 nm [15] [16] |

| Lateral Spatial Resolution | ≥ 7.5 μm [14] | < 10 nm, can be as small as 8 nm [15] [16] |

| Detectable Elements | All elements except Hydrogen (H) and Helium (He) [3] | All elements higher than Helium (He) [16] |

| Primary Excitation Source | X-rays (e.g., Al Kα) [11] | Electron Beam (0.1 – 25 keV) [16] |

| Primary Information | Elemental identity, concentration, and chemical state [3] [14] | Elemental identity and distribution [15] [13] |

| Quantitative Accuracy | ±5-30% (with or without standards) [3] | ~10% with standards; ~50% without standards [13] |

| Sample Compatibility | Conductors, Semiconductors, and Insulators [3] | Primarily Conductors and Semiconductors [3] |

Critical Parameter Analysis

Analysis Depth

Both XPS and AES are highly surface-sensitive techniques with average analysis depths of approximately 5 nanometers [15] [14]. This shallow information depth is a consequence of the inelastic mean free path of the emitted electrons (photoelectrons for XPS and Auger electrons for AES), which is the average distance an electron can travel in a solid without losing energy. Only electrons that originate within this short distance from the surface can escape and be detected, making both techniques ideal for studying thin films, surface contaminants, and oxidation layers [13].

Spatial Resolution

Lateral spatial resolution is the most differentiating parameter between these two techniques. AES excels in this area, achieving a spatial resolution of <10 nm, with state-of-the-art systems reaching down to 8 nm [15] [16]. This high resolution is possible because the primary electron beam can be focused to a very fine spot. In contrast, the lateral resolution in XPS is typically on the micrometer scale (e.g., 7.5 μm), limited by the difficulty in focusing X-ray beams [3] [14]. This makes AES the preferred technique for mapping elemental distributions at the nanoscale, such as in semiconductor devices or nanoparticle analysis [15].

Detectable Elements

Both techniques can detect all elements from Lithium (Li) to Uranium (U), with AES also capable of detecting elements heavier than Helium [16] [3]. A notable difference is that XPS cannot effectively detect Hydrogen and Helium [3]. The detection limits for both techniques are in the range of 0.1 to 1 atomic percent, though sensitivity can be higher for certain elements with AES due to the ability to use a more intense, focused primary beam [16] [3] [13].

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Standard Operational Workflows

The following diagrams illustrate the standard experimental workflows for XPS and AES analysis, from sample preparation to data interpretation.

Diagram 1: AES Experimental Workflow

Diagram 2: XPS Experimental Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Instrumentation and Reagents

Successful surface analysis requires specific instrumentation and materials. The table below details key components of a typical XPS or AES analysis system.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Surface Analysis

| Item | Function/Description | Technical Notes |

|---|---|---|

| High Vacuum Chamber | Maintains ultra-high vacuum (UHV) environment (< 5x10⁻⁹ Torr for AES) to prevent surface contamination and allow electron detection without scattering. | Essential for both XPS and AES [13]. |

| Conductive Sample Mounts | Provides a stable, electrically conductive platform for mounting samples. | Crucial for AES to prevent charging; important for XPS on insulators [3]. |

| Mono-energetic X-ray Source (Al Kα, Mg Kα) | Primary excitation source for XPS. Ejects photoelectrons from the sample. | Energy is 1486.6 eV for Al Kα [14]. |

| Field Emission Electron Gun | Primary excitation source for AES. Generates a finely focused, high-intensity electron beam. | Enables high spatial resolution (< 10 nm) [15] [13]. |

| Hemispherical/Cylindrical Mirror Analyzer (CHA/CMA) | Measures the kinetic energy of emitted electrons with high resolution. | CHA is standard in modern XPS and AES systems [13] [12]. |

| Ion Sputtering Gun (Ar⁺) | Removes surface layers for depth profiling and sample cleaning. | Can cause artifacts like preferential sputtering [17] [13]. |

| Reference Materials (Au, Cu, Ag Foils) | Used for energy scale calibration and quantification. | Ensures accuracy and comparability of data [13]. |

Advanced Applications and Integrated Protocols

AES for Nanoscale Particle Analysis

Objective: To determine the elemental composition of micro-scale or sub-micrometer particles, such as solder joints or contaminants. Protocol:

- Sample Preparation: The sample, such as a polished cross-section of lead-free solder, is mounted on a conductive stub to prevent charging [15].

- SEM Imaging: The area of interest is located using a high-resolution Scanning Electron Microscope (SEM) integrated with the AES system [15].

- AES Point Analysis & Mapping: A focused electron beam (e.g., 20 kV, 5 nA) is rastered over the particle. Emitted Auger electrons are collected to create elemental maps (e.g., Sn (blue), Ag (red), Cu (green)) [15].

- Data Interpretation: The distinct colors in the overlay map reveal the spatial distribution of elements, identifying phases and potential contaminants.

XPS Chemical State Analysis for Catalysts

Objective: To identify not only the presence of an element but also its chemical state, as in the case of molybdenum on a catalyst surface. Protocol:

- Sample Preparation: The catalyst sample is securely mounted in the UHV chamber.

- Spectrum Acquisition: A monochromatic X-ray beam is focused on the sample, and high-resolution spectra are acquired over a narrow energy range covering the Mo 3d photoelectron peaks.

- Peak Fitting & Chemical Shift Analysis: The resulting spectrum is deconvoluted. The binding energy for elemental Mo is found at 227.6 eV, while Mo in the +6 oxidation state (MoO₃) shows a peak at 232.7 eV [3].

- Quantification: The relative areas under the peaks for different chemical states are calculated to determine their abundance on the surface.

Depth Profiling with Sputtering

Objective: To determine the in-depth composition of a thin film structure. Protocol (Common to both XPS and AES):

- Initial Surface Analysis: A spectrum is acquired from the as-received surface.

- Cyclic Sputtering and Analysis: An ion beam (often Ar⁺) sputters the surface for a predetermined time to remove a thin layer. The newly exposed surface is then analyzed by XPS or AES. This cycle is repeated multiple times [17] [13].

- Data Reconstruction: The elemental concentrations from each cycle are plotted against sputter time or estimated depth to create a depth profile. Techniques like Zalar rotation can be employed to minimize artifacts like differential sputtering [13].

XPS and AES are powerful, complementary surface analysis techniques with distinct strengths dictated by their fundamental physical parameters. AES is unparalleled for high lateral resolution mapping at the nanoscale, making it ideal for failure analysis in semiconductors and investigating heterogeneous materials. Its requirement for conductive samples, however, can be a limitation. XPS provides superior chemical state information and is applicable to a wider range of materials, including insulators, but with lower spatial resolution.

The choice between them hinges on the specific research question. If the goal is to identify oxidation states or analyze insulating materials, XPS is the definitive choice. If the problem requires mapping elemental distributions with nanoscale precision on a conductive sample, AES is the superior tool. Often, a combined approach, utilizing the strengths of both techniques, provides the most comprehensive understanding of a material's surface properties.

Essential Instrumentation Components and Operational Requirements

Surface analysis is a critical field in materials science, chemistry, and drug development, where the outermost layers of a material often determine its properties and performance. Two powerful techniques for surface characterization are X-ray Photoelectron Spectroscopy (XPS), also known as Electron Spectroscopy for Chemical Analysis (ESCA), and Auger Electron Spectroscopy (AES). Both techniques provide information about the elemental composition and chemical state of the top few nanometers of a material surface, but they differ significantly in their instrumentation, operational requirements, and application suitability [18] [19].

Understanding the essential components and operational parameters of these techniques is crucial for researchers selecting the appropriate method for their specific analytical needs. This guide provides a detailed comparison of XPS and AES instrumentation, focusing on their key components, performance characteristics, and optimal application scenarios to inform method selection in research and development environments.

Fundamental Principles and Instrumentation

X-ray Photoelectron Spectroscopy operates by irradiating a sample with X-rays and measuring the kinetic energy of ejected photoelectrons. According to the photoelectric effect, the binding energy of these electrons is calculated using the relationship: Ebinding = Ephoton - Ekinetic - φ, where Ephoton is the incident X-ray energy, Ekinetic is the measured electron kinetic energy, and φ is the work function of the spectrometer [18]. This binding energy serves as a fingerprint for elemental identification and chemical state determination.

The essential components of an XPS instrument include:

- X-ray source: Typically monochromated Al Kα radiation (1486.6 eV) generated by electron bombardment of an aluminum anode. Monochromation using quartz crystals improves energy resolution by providing a narrow spread of X-ray energies [20] [21].

- Electron analyzer: A hemispherical analyzer acts as a band-pass filter, allowing electrons of specific kinetic energies to reach the detector. Electron lenses focus and steer emitted photoelectrons into the analyzer [20].

- Ultra-high vacuum (UHV) system: Maintains pressure below 10-9 Torr to prevent scattering of photoelectrons by gas molecules and to maintain surface cleanliness [20] [18].

- Charge neutralization system: An electron flood gun compensates for surface charging on insulating samples by providing low-energy electrons [20] [18].

- Ion source: Typically an argon ion gun for sample cleaning and depth profiling through sputter removal of surface layers [20] [18].

- Detection and data system: Electron detectors count arriving electrons, and sophisticated software controls instrumentation and processes data [20].

Auger Electron Spectroscopy utilizes a focused electron beam to excite atoms in the sample, resulting in the emission of Auger electrons during the relaxation process. The kinetic energy of these electrons is characteristic of the emitting element and is independent of the incident beam energy. AES instrumentation shares some similarities with XPS but has distinct differences in key components:

- Electron source: A focused electron gun (typically 3-20 keV) provides the primary excitation, allowing for much smaller analysis areas compared to XPS [19].

- Electron analyzer: Similar hemispherical analyzer as used in XPS, but often optimized for different energy ranges and spatial resolution.

- UHV system: Similarly requires ultra-high vacuum conditions for electron mean free path preservation and surface cleanliness.

- Detection system: Electron detectors similar to those in XPS, but often coupled with scanning capabilities for elemental mapping.

A key advantage of AES is its superior spatial resolution, as electron beams can be focused to spot sizes approximately an order of magnitude smaller than X-ray beams [19]. However, the high-energy electron beam can cause sample damage, particularly to sensitive organic materials and polymers.

Operational Workflow Comparison

The following diagram illustrates the fundamental operational principles and logical relationships between components in XPS and AES systems:

Performance Comparison and Experimental Data

Technical Specifications Comparison

Table 1: Instrumentation and performance comparison between XPS and AES

| Parameter | XPS | AES |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Excitation Source | X-rays (Al Kα, Mg Kα) [20] [18] | Focused electron beam (3-20 keV) [19] |

| Spatial Resolution | ~10-100 μm [19] | ~10 nm - 1 μm (order of magnitude better than XPS) [19] |

| Information Depth | Top 1-10 nm [20] [18] | Few nm (similar to XPS) [19] |

| Elemental Range | All elements except H and He [19] | All elements except H and He [19] |

| Chemical Bonding Information | Excellent (chemical shifts ~0.1 eV resolution) [18] | Limited (fewer reference databases) [19] |

| Quantitative Accuracy | ±10% with standard sensitivity factors [18] | Similar to XPS with proper calibration [22] |

| Sample Conductivity Requirements | Suitable for both conductors and insulators (with charge compensation) [20] [19] | Primarily for conducting samples (charging issues with insulators) [19] |

| Typical Analysis Time | Minutes to hours (depending on elements and resolution) | Generally faster than XPS for comparable data [19] |

| Sample Damage Potential | Lower (X-ray induced damage possible but less severe) | Higher (electron beam can damage sensitive materials) [19] |

| Depth Profiling Capability | Yes (with monatomic or gas cluster ion beams) [20] | Excellent (high sputtering rates with precise control) [19] |

Quantitative Analysis Capabilities

Both XPS and AES provide quantitative elemental composition data through the measurement of peak intensities and application of sensitivity factors. The general expression for quantitative analysis in XPS is:

Cx = (Ix/Sx) / (ΣIi/Si)

where Cx is the concentration of element x, Ix is the measured intensity, Sx is the elemental sensitivity factor, and ΣIi/Si is the sum of intensity/sensitivity factor ratios for all detected elements [18].

For accurate quantification, both techniques require careful calibration of the electron spectrometer transmission function and detector sensitivity energy dependencies [22]. Modern instruments incorporate standardized calibration procedures to ensure quantitative accuracy of approximately ±10% for most elements [18].

Table 2: Analytical capabilities for different material types

| Material Type | Preferred Technique | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Polymers & Organic Materials | XPS | Minimal radiation damage; effective charge neutralization available [20] [19] |

| Inorganic Semiconductors | Both | AES for high spatial resolution; XPS for chemical state information [19] |

| Metals & Alloys | Both | AES for grain boundary analysis; XPS for oxide layer characterization [18] [19] |

| Ceramics & Oxides | XPS | Better charge compensation; superior chemical state information [20] [18] |

| Powders & Porous Materials | XPS | Less susceptible to charging issues; better for insulating materials [20] |

| Multilayer Thin Films | AES | Superior depth resolution for thin layer structures [19] |

| Biomaterials | XPS | Lower damage potential; better for radiation-sensitive biological materials [20] |

Detection Limits and Sensitivity

Both XPS and AES offer similar detection limits typically in the range of 0.1-1.0 atomic percent for most elements. The fundamental limitations arise from the electron emission cross-sections, analyzer transmission efficiencies, and background noise levels. For XPS, monochromated X-ray sources provide better signal-to-noise ratios and higher energy resolution, enabling more precise chemical state identification [20] [21]. AES generally offers faster data acquisition, particularly for elemental mapping applications, due to the higher brightness of electron sources compared to X-ray sources.

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Sample Preparation Procedures

Proper sample preparation is critical for both XPS and AES analysis. The following protocols ensure reliable and reproducible results:

Universal Preparation Steps:

- Sample Cleaning: Remove adventitious carbon and other contaminants using appropriate solvents. For AES, note that the electron beam may vaporize volatile organic compounds during analysis [19].

- Mounting: Secure samples to appropriate holders using conductive tapes or clips. For insulating samples in XPS, specialized mounting may be required for optimal charge compensation.

- Electrical Contact: Ensure good electrical connection between sample and holder to minimize charging effects. For XPS analysis of insulators, this is less critical due to the electron flood gun [20].

- Load-Lock Introduction: Transfer samples via a load-lock chamber to maintain the ultra-high vacuum in the analysis chamber [20].

Material-Specific Considerations:

- Powders: Press into indium foil or spread as thin layer on conductive tape

- Non-conducting materials: For XPS, use thin sections and ensure proper charge neutralization system calibration [20]

- Air-sensitive materials: Use inert atmosphere transfer vessels to prevent surface oxidation

- Biological specimens: May require freeze-drying or special fixation to preserve structure under vacuum

Data Acquisition Protocols

XPS Survey Scans:

- Set pass energy to 100-200 eV for optimal sensitivity

- Acquire spectrum over binding energy range of 0-1100 eV

- Use step size of 0.5-1.0 eV with dwell times of 50-100 ms

- Identify all detectable elements from characteristic photoelectron peaks [18]

XPS High-Resolution Scans:

- Set pass energy to 20-50 eV for better energy resolution

- Use step size of 0.05-0.1 eV with longer dwell times (100-200 ms)

- Acquire regions for each detected element with sufficient range to observe chemical shifts

- Collect multiple scans to improve signal-to-noise ratio for trace elements [18]

AES Survey Scans:

- Set primary beam energy appropriate for the sample (typically 5-10 keV)

- Acquire spectrum in differential mode (dN(E)/dE) for better peak visibility

- Scan kinetic energy range from 0-2000 eV

- Identify elements from characteristic Auger peaks [19]

AES Mapping:

- Set primary beam parameters for desired spatial resolution

- Select specific Auger transitions for each element of interest

- Raster the electron beam across the sample area

- Acquire peak intensity maps at each pixel location [19]

Depth Profiling Methodologies

XPS Depth Profiling:

- Alternate between ion sputtering and data acquisition cycles

- Use monatomic ion beams (Ar+) for inorganic materials or gas cluster ion beams (GCIB) for organic materials to minimize damage [20]

- Select key photoelectron peaks to monitor as function of sputtering time

- Convert sputtering time to depth using calibrated sputter rates for similar materials [18]

AES Depth Profiling:

- Use simultaneous sputtering and analysis for faster profiling

- Employ lower energy ions for better depth resolution

- Monitor selected Auger peaks during continuous sputtering

- Optimize sputter rate based on material properties and depth resolution requirements [19]

The following diagram illustrates the standard workflow for surface analysis experiments:

The Researcher's Toolkit: Essential Instrument Components

Table 3: Essential components and their functions in XPS and AES instrumentation

| Component | Function | XPS | AES |

|---|---|---|---|

| Excitation Source | Generates primary radiation/particles for sample excitation | X-ray gun (Al/Mg anode) [20] [18] | Electron gun (thermal or field emission) [19] |

| Monochromator | Filters excitation source to narrow energy distribution | Quartz crystal monochromator [20] [21] | Not typically used |

| Hemispherical Analyzer | Energy discrimination of emitted electrons | Standard (FAT or FRR modes) [21] | Standard (similar to XPS) [19] |

| UHV System | Maintains low pressure for electron mean free path | Essential (<10⁻⁹ Torr) [20] [18] | Essential (<10⁻⁹ Torr) [19] |

| Ion Source | Surface cleaning and depth profiling | Argon ion source (monatomic or cluster) [20] | Argon ion source (typically monatomic) [19] |

| Charge Neutralizer | Compensates charging on insulating samples | Low-energy electron flood gun [20] [18] | Limited effectiveness [19] |

| Sample Stage | Positions sample for analysis | Multi-axis manipulator with heating/cooling | Multi-axis manipulator, often with higher precision |

| Detection System | Counts electrons transmitted by analyzer | Electron multipliers or position-sensitive detectors [21] | Similar to XPS detectors [19] |

| Optical Microscope | Sample viewing and area selection | Integrated with stored navigation views [20] | Often integrated with SEM capabilities |

| Load-Lock Chamber | Sample introduction without breaking vacuum | Standard feature [20] | Standard feature [19] |

Application-Specific Methodology Selection

Chemical State Analysis - XPS Protocol

For detailed chemical state analysis, XPS is unequivocally superior due to well-established chemical shift databases and higher energy resolution. The experimental protocol includes:

High-Resolution Regional Scans:

- Use monochromated X-ray source for optimal energy resolution [20]

- Set pass energy to 20 eV or lower for high spectral resolution

- Acquire multiple scans to improve statistics while minimizing radiation damage

- Use step sizes of 0.05-0.1 eV to adequately sample peak shapes

Energy Referencing:

- For conductive samples: reference to Fermi edge or known metallic peak

- For insulating samples: use adventitious carbon (C 1s at 284.8 eV) as reference [18]

- Document reference method in all reports for reproducibility

Peak Fitting Procedure:

- Use appropriate background subtraction (Shirley, Tougaard, or linear)

- Employ chemically realistic peak models with proper constraints

- Maintain consistent full-width-at-half-maximum (FWHM) for similar chemical states

- Report all fitting parameters and uncertainties

High-Spatial-Resolution Mapping - AES Protocol

When spatial resolution below 1 μm is required, AES provides significant advantages:

Optimal Instrument Conditions:

- Use field emission electron source for smallest probe size

- Select primary beam energy based on sample properties and desired resolution

- Optimize beam current for adequate signal while minimizing damage

Mapping Acquisition:

- Select characteristic Auger transitions for each element

- Define raster area and pixel density based on feature size

- Acquire peak-minus-background maps for quantitative interpretation

- Use multiplex acquisition for multiple elements to ensure registration

Data Interpretation:

- Correlate AES maps with secondary electron images for morphological context

- Account for potential sample damage during extended acquisitions

- Use multivariate analysis techniques for complex spectral datasets

The choice between XPS and AES depends primarily on the specific analytical requirements of the investigation. XPS is generally preferred when chemical state information, analysis of insulating materials, or minimal sample damage are primary concerns. Its strengths in quantitative analysis and comprehensive databases make it invaluable for polymer characterization, oxide film analysis, and biological interface studies [20] [18] [19].

AES excels in applications requiring high spatial resolution, rapid depth profiling, and analysis of conductive materials. Its superior mapping capabilities and faster acquisition times make it ideal for semiconductor device analysis, grain boundary segregation studies, and failure analysis of microelectronic components [19].

For comprehensive surface characterization, many research facilities utilize both techniques in a complementary approach, leveraging the chemical specificity of XPS with the high spatial resolution of AES. Understanding the essential instrumentation components and operational requirements outlined in this guide enables researchers to select the optimal technique for their specific surface analysis challenges and correctly interpret the resulting data within the limitations of each method.

The Role of Surface Analysis in Modern Materials Science and Biomedical Research

Surface analysis techniques are indispensable tools for characterizing the chemical and elemental composition of material surfaces, with X-ray Photoelectron Spectroscopy (XPS) and Auger Electron Spectroscopy (AES) standing as two of the most prominent methods. The choice between them is critical, as it dictates the type of information that can be obtained, the kinds of samples that can be studied, and the ultimate success of a research project. This guide provides an objective comparison of XPS and AES to help researchers select the optimal technique for their specific applications in materials science and biomedical research.

Analytical Principle and Information Depth

At their core, both XPS and AES are electron spectroscopy techniques that probe the outermost layers of a solid sample. However, their excitation mechanisms and the fundamental information they provide differ significantly.

XPS Principle

XPS, also known as Electron Spectroscopy for Chemical Analysis (ESCA), uses a beam of X-rays to irradiate the sample surface [23]. This irradiation causes photoelectrons to be emitted from the core levels of atoms within the top 1–10 nm of the material [23]. The measured kinetic energy of these photoelectrons is used to determine their binding energy, which is characteristic of the parent element and its chemical state [23] [9]. This chemical state sensitivity is a key strength of XPS, allowing researchers to distinguish, for example, between metallic silicon and silicon dioxide, or between different oxidation states of a metal.

AES Principle

AES, in contrast, uses a finely focused electron beam as the primary excitation source [24]. This beam causes atoms to undergo a process known as the Auger effect, resulting in the emission of Auger electrons. The kinetic energy of these Auger electrons is measured and is also characteristic of the emitting element [24]. While AES can sometimes provide chemical state information from peak shape and position, it is generally considered less straightforward for this purpose than XPS. The average depth of analysis for AES is approximately 5 nm [24].

The following diagram illustrates the fundamental processes and information pathways for both techniques:

Technical Comparison and Experimental Data

The fundamental differences in the principles of XPS and AES lead to distinct performance characteristics, making each technique better suited for specific types of analysis. The table below summarizes their key technical parameters for direct comparison.

Table 1: Technical Comparison of XPS and AES

| Parameter | XPS (ESCA) | AES |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Excitation Source | X-ray beam [23] | Focused electron beam (typically 3-25 keV) [24] |

| Detected Particle | Photoelectrons [23] | Auger electrons [24] |

| Information Depth | Top 1-10 nm [23] | ~5 nm (average) [24] |

| Lateral Resolution | Typically > 10 µm (can be ~3 µm with μ-XPS) [23] | As small as 8 nm [24] |

| Elemental Range | All elements except H and He [25] | All elements except H and He |

| Chemical State Info. | Excellent - via chemical shifts in binding energy [23] [9] | Moderate - via peak shape and position changes [24] |

| Quantitative Analysis | Excellent - inherently quantitative with sensitivity factors [25] | Good - requires standards and is less straightforward than XPS |

| Sample Damage | Generally low (X-ray induced damage possible for sensitive materials) | Higher risk due to focused electron beam, especially on polymers and organics |

Supporting Experimental Data and Reproducibility

The reliability of data from both techniques is paramount. The National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) provides critical databases to support quantitative analysis:

- NIST XPS Database (SRD 20): Contains over 33,000 data records for peak identification, binding energies, and chemical shifts [26].

- NIST Electron Inelastic-Mean-Free-Path Database (SRD 71): Provides values essential for quantitative depth analysis in both XPS and AES [26].

- NIST Database for the Simulation of Electron Spectra (SESSA) (SRD 100): Can simulate both XPS and AES spectra for complex nanostructures to aid in interpretation and method validation [26].

A significant challenge noted in the literature is the potential for poor reporting and misinterpretation of XPS data by inexperienced users, which can contribute to a "reproducibility crisis" in scientific literature [25]. To ensure reliable results, researchers are encouraged to follow established practical guides and standards [25].

Experimental Protocols and Workflows

A successful surface analysis experiment requires careful planning and execution. The workflow, from sample preparation to data interpretation, is critical for obtaining meaningful results.

Protocol 1: Standard XPS Analysis for Surface Chemical State Identification

This protocol is designed to determine the elemental composition and chemical states on a material's surface, ideal for studying oxide layers, functionalized surfaces, or contaminants [23] [9].

- Sample Preparation: For solid samples, secure them on a holder using double-sided conductive tape or metal clamps. For powders, press them into an indented sample holder or onto a sticky tape. Critical Note: Handle samples with gloves and tweezers to avoid contamination from fingerprints. If the sample is an electrical insulator, charge compensation using a low-energy electron flood gun is essential [23].

- Instrument Setup and Calibration: Insert the sample into the ultra-high vacuum (UHV) chamber. Verify the energy scale calibration of the spectrometer using a standard material, such as clean gold (Au 4f7/2 at 84.0 eV) or copper (Cu 2p3/2 at 932.67 eV).

- Preliminary Survey Spectrum: Collect a wide energy range (e.g., 0-1100 eV binding energy) survey scan with a low energy resolution (high pass energy). This identifies all elements present on the surface [25].

- High-Resolution Regional Spectra: For each element of interest identified in the survey, collect a high-energy-resolution spectrum (narrow energy window) of its core-level peaks (e.g., C 1s, O 1s, N 1s, Si 2p). Use appropriate step sizes and dwell times to ensure good counting statistics.

- Data Processing and Interpretation:

- Charge Referencing: If the sample is an insulator, reference the spectra to the adventitious carbon C 1s peak (typically set to 284.8 eV).

- Background Subtraction: Apply a suitable background (e.g., Shirley or Tougaard).

- Peak Fitting: Deconvolute complex peaks using synthetic components representing different chemical states. Reference databases like NIST SRD 20 should be used for chemical shift identification [26].

- Quantification: Calculate atomic concentrations using the peak areas and relative sensitivity factors (RSFs) provided by the instrument software.

Protocol 2: AES Depth Profiling for Thin Film Interface Analysis

This protocol is used to determine the compositional variation as a function of depth, crucial for analyzing multilayer thin films, coatings, and diffusion at interfaces [24].

- Sample Preparation and Initial Analysis: Prepare and introduce the sample as in the XPS protocol. First, acquire a survey AES spectrum from the as-received surface to confirm the initial composition.

- Sputter Source Setup: Select an appropriate ion source (e.g., Ar+ ions) and set the ion energy and current density to achieve the desired sputter rate for the material. The sputter rate must be calibrated for a known standard (e.g., SiO₂ on Si) under identical conditions.

- Cyclic Sputtering and Analysis:

- Sputter Cycle: Remove a thin layer of material (e.g., 1-10 nm) by ion bombardment for a predetermined time.

- Analysis Cycle: Move the sample back to the analysis position. Acquire either survey spectra or high-resolution spectra for specific elements of interest. High lateral resolution AES can be used to analyze small features [24].

- Repetition: Repeat the sputter-and-analyze cycle until the substrate material or the full layer structure has been profiled.

- Data Compilation and Analysis: Plot the atomic concentration of each element (derived from the peak-to-peak heights in the differentiated AES spectra or from peak areas) as a function of sputter time or estimated depth.

The following flowchart visualizes the decision-making process for selecting and applying these techniques:

Application Performance in Key Research Fields

The suitability of XPS and AES varies dramatically across different application domains, driven by their inherent strengths and weaknesses.

Materials Science and Nanotechnology

- XPS Applications: XPS is the go-to technique for studying oxide layers on metals, corrosion products, catalyst surfaces, and the chemical composition of polymers [27] [9]. Its ability to provide chemical state information is critical for understanding surface reactions and functionality. For example, it can distinguish between Si, Si₂O, SiO, and SiO₂ in a growing oxide layer [27]. Angle-Resolved XPS (ARXPS) is uniquely powerful for analyzing the thickness and composition of ultra-thin films without the need for sputtering [23].

- AES Applications: AES excels in failure analysis and microelectronics due to its high spatial resolution. It is ideal for identifying sub-micron contamination particles, analyzing grain boundary segregation, and characterizing thin film structures in semiconductor devices with nanometer-scale features [24]. Its strength lies in high-resolution elemental mapping and depth profiling of small, defined areas.

Biomedical Research

In biomedical applications, XPS is the dominant technique due to its lower propensity for damaging sensitive organic materials and its superior ability to characterize chemical states.

- Surface Functionalization: XPS is used to verify the success of surface modifications on biomaterials, such as the introduction of amine or carboxyl groups, by identifying the specific chemical bonds formed [7].

- Implant and Device Analysis: It characterizes the surface chemistry of implants, assessing coatings, corrosion, and the nature of biofouling layers [27] [7].

- Cell-Material Interactions: XPS helps understand the chemical state of adsorbed proteins and other biomolecules on material surfaces, which is crucial for studying biocompatibility and host responses [7].

AES is rarely used for direct analysis of organic or biological surfaces because the focused electron beam causes rapid degradation and damage to the sample.

Table 2: Application-Based Technique Selection Guide

| Research Field | Exemplary Use Case | Recommended Technique | Rationale |

|---|---|---|---|

| Catalysis | Identifying chemical states of active sites on a catalyst surface [27]. | XPS | Superior chemical state information and quantification. |

| Microelectronics | Analyzing a sub-100 nm defect on a semiconductor wafer [24]. | AES | Superior spatial resolution for small feature analysis. |

| Polymers & Biomaterials | Verifying the presence of a specific functional group on a drug-eluting stent [27] [7]. | XPS | Excellent for organic chemistry and low damage potential. |

| Metals & Corrosion | Measuring the composition and thickness of a passive oxide film on steel [27]. | XPS | Non-destructive depth profiling (ARXPS) and chemical state analysis. |

| Thin Film Coatings | Depth profiling of a multilayer optical coating (e.g., on glass) [23] [27]. | Both | XPS for chemistry of each layer, AES for higher depth resolution. |

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Successful surface analysis relies on more than just the spectrometer. The following table lists key materials and tools essential for preparing and analyzing samples.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Surface Analysis

| Item | Function/Description | Critical Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Conductive Tapes & Adhesives | Mounting powder or insulating samples to a sample stub. | Use high-purity carbon tapes to minimize contamination for trace analysis. |

| Reference Materials (Au, Cu, Ag) | Calibrating the binding energy scale of the XPS spectrometer [25]. | Regular calibration is essential for accurate and reproducible binding energy values. |

| Charge Neutralization Flood Gun | Supplies low-energy electrons/ions to neutralize positive charge buildup on insulating samples [23]. | Critical for non-conductive samples like polymers, ceramics, and biological specimens. |

| Gas Cluster Ion Source (GCIS) | A source of Arn+ clusters (n=1000-5000) for sputtering organic and polymeric materials [23] [27]. | Enables depth profiling of soft materials without the damage caused by monatomic ion beams. |

| NIST Standard Databases | Provide reference spectra, binding energies, and cross-section data for peak identification and quantification [26]. | SRD 20 (XPS Database) and SRD 100 (SESSA) are invaluable for data interpretation and validation [26]. |

The decision between XPS and AES is not a matter of one technique being universally superior to the other, but rather of matching the technique's strengths to the specific analytical question.

- Choose XPS when your primary need is for quantitative elemental analysis, detailed chemical state information, and the analysis of a wide range of materials, including electrical insulators and sensitive organic/biological layers. Its value is highest in applications like catalyst characterization, polymer surface modification, biocompatibility studies, and corrosion science [27] [9] [7].

- Choose AES when your analysis requires high spatial resolution (nanometer-scale) for elemental mapping or point analysis on electrically conductive samples. Its niche is in the failure analysis of microelectronic devices, the study of grain boundary segregation in metals, and high-resolution depth profiling of inorganic thin films [24].

For the most complex problems, the techniques are complementary. A combined XPS and AES approach can provide a comprehensive picture, marrying the high chemical sensitivity of XPS with the high spatial resolution of AES. By understanding their fundamental principles and performance characteristics, researchers can effectively leverage these powerful tools to advance discovery in both materials science and biomedical research.

Practical Applications: When and How to Use XPS and AES in Research

XPS for Chemical State Analysis and Quantitative Composition

X-ray Photoelectron Spectroscopy (XPS) stands as a premier analytical technique for determining both the chemical state and quantitative composition of material surfaces. As a surface-sensitive method, XPS probes the top 1-10 nanometers of a sample, making it indispensable for understanding surface chemistry in fields ranging from materials science to biomedical device development [9] [27]. This guide examines the specific capabilities of XPS for chemical state analysis and quantification, framing these strengths within a comparative context with Auger Electron Spectroscopy (AES), another fundamental surface analysis technique.

The fundamental principle underlying XPS is the photoelectric effect, where a sample irradiated with X-rays emits photoelectrons whose kinetic energies are characteristic of the elements from which they originated and their chemical environments [1] [11]. This emission process differs fundamentally from AES, where the initial ionization leads to the emission of an Auger electron [11]. It is this fundamental difference that grants XPS its distinctive capabilities in chemical state identification.

Comparative Technique: XPS vs. AES

While both XPS and AES are surface-sensitive techniques operating under ultra-high vacuum conditions, their differing physical principles and experimental approaches lead to distinct analytical strengths [1]. The choice between them hinges on the specific information required from a sample.

Key Analytical Differences

The table below summarizes the core distinctions between XPS and AES relevant to chemical state analysis and quantification:

Table 1: Comparison of XPS and AES for Surface Analysis

| Analytical Feature | XPS (X-ray Photoelectron Spectroscopy) | AES (Auger Electron Spectroscopy) |

|---|---|---|

| Fundamental Principle | Photoelectric effect [1] [11] | Auger effect [1] [11] |

| Primary Excitation Source | X-ray photons [1] | Energetic electron beam [1] |

| Chemical State Information | Excellent; provides direct data on oxidation states and chemical bonding via chemical shifts [1] [28] | Limited; indirect inference from line shape changes, often less definitive [1] |

| Quantitative Capability | Good; based on scaling intensities by relative sensitivity factors [29] [25] | Possible, but historically less straightforward, especially with differential spectra [29] |

| Typical Depth of Analysis | Top 1-10 nm [9] [27] | Slightly deeper than XPS, but still surface-sensitive [11] |

| Spatial Resolution | Good (typically micron-scale) [1] [11] | Excellent (can be nanometer-scale with focused beams) [1] |

| Detection of Light Elements | Excellent, including lithium [27] | Effective, but XPS is often preferred for light elements [1] |

Choosing the Right Technique

The decision to use XPS or AES depends entirely on the analytical question:

- Use XPS when: The primary goal is to identify chemical states or oxidation states (e.g., distinguishing Si, SiO₂, and Si₃N₄), perform quantitative analysis of surface composition, or detect light elements like lithium in battery materials [1] [27] [28].

- Use AES when: The requirement is for high-spatial resolution mapping of elemental distributions or analysis of very small features on the nanometer scale, and detailed chemical state information is secondary [1].

For the remainder of this guide, we will focus on the specific methodologies and applications of XPS for chemical state analysis and quantitative composition.

XPS for Chemical State Analysis

The power of XPS to reveal chemical state information stems from the chemical shift—a small change in the measured binding energy of a photoelectron caused by the element's chemical environment [28].

The Chemical Shift Phenomenon

When the oxidation state or chemical bonding of an atom changes, the electron density around it is altered. For example:

- Oxidation: An atom losing electron density (e.g., a metal being oxidized) experiences a decrease in shielding of its core electrons by the valence electrons. This results in an increase in the binding energy of the emitted photoelectrons [28].

- Reduction: Conversely, an atom gaining electron density experiences an increase in shielding and a consequent decrease in binding energy.

This shift allows researchers to distinguish between, for instance, elemental silicon (Si⁰), silicon carbide (Si-C), silicon nitride (Si₃N₄), and silicon dioxide (SiO₂) based on the precise binding energy of the Si 2p photoelectron peak [28].

Experimental Protocol: Chemical State Analysis by High-Resolution XPS

Obtaining meaningful chemical state information requires a meticulous experimental and data analysis workflow.

Diagram 1: XPS chemical state analysis workflow.

Step-by-Step Methodology:

- Sample Preparation: Introduce the sample into the ultra-high vacuum (UHV) chamber. Ensure the surface is clean and representative of the material to be studied. Surface cleaning by Ar⁺ ion sputtering may be employed if contamination is present [25].

- Survey Spectrum Acquisition: Collect a wide energy range scan (e.g., 0-1100 eV binding energy) to identify all elements present on the surface [25] [28].

- High-Resolution Spectrum Acquisition: For each element of interest, collect a high-resolution spectrum over a narrow energy window (e.g., 10-30 eV). This requires a sufficient number of scans and appropriate step size to achieve good signal-to-noise ratio [28].

- Charge Correction: Correct for specimen charging by referencing a known peak position. A common method is to set the C 1s peak from adventitious carbon to 284.5 eV [28]. Metallic samples can be referenced to their own Fermi edge.

- Background Subtraction: Remove the inelastically scattered electron background from the high-resolution spectrum. The Shirley background is a standard method for this purpose [28].

- Peak Fitting: Decompose the complex spectrum into its individual chemical components using non-linear least squares fitting with mixed Gaussian-Lorentzian line shapes (e.g., Voigt function) [28].

- The Full Width at Half Maximum (FWHM) of component peaks should be consistent and chemically reasonable.

- The number of peaks used in the fit should be justified by the chemistry of the system.

- Interpretation: Identify the chemical states corresponding to each fitted component by comparing their binding energies to established databases and literature values [28].

Table 2: Example Chemical Shifts for Common Elements

| Element & Transition | Chemical State | Approximate Binding Energy (eV) | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| C 1s | C-C / C-H (adventitious carbon) | 284.5 | Common charge reference [28] |

| C-O (alcohol/ether) | 286.1 - 286.5 | ||

| O-C=O (carbonyl/carboxyl) | 288.1 - 289.0 | ||

| O 1s | Metal Oxide (O²⁻) | 529 - 531 | |

| C-OH / Adsorbed H₂O | 532.5 - 533.5 | [28] | |

| Si 2p | Elemental Silicon (Si⁰) | ~99 | |

| Silicon Dioxide (SiO₂) | 103 - 104 | Shift of ~4 eV from Si⁰ |

Quantitative Composition with XPS

XPS is not merely a qualitative tool; it can provide reliable quantitative data on the atomic concentration of elements within the analysis volume [29] [25].

Fundamentals of XPS Quantification

The intensity of a photoelectron peak from an element A in a homogeneous material is given by simplified equation below. In practice, quantification uses Relative Sensitivity Factors (RSFs) to scale measured intensities [29]. The atomic fraction of element A is calculated as:

[ XA = \frac{IA / SA}{\sumi (Ii / Si)} ]

Where:

- ( X_A ) is the atomic fraction of element A.

- ( I_A ) is the measured peak intensity (area) for element A.

- ( S_A ) is the relative sensitivity factor for element A.

- The denominator is the sum of the intensity/RSF ratios for all detected elements.

These RSFs, which account for factors like photoionization cross-section and spectrometer transmission, are typically provided by instrument manufacturers or derived from standard databases [29] [28].

Experimental Protocol: Quantitative XPS Analysis

Accurate quantification depends on careful data collection and processing.

Diagram 2: XPS quantitative analysis workflow.

Step-by-Step Methodology: